Drug-Related Arrests in a Cohort of Public Mental Health Service Recipients

The many problems associated with substance abuse among persons with severe mental illness have been a prominent focus of the psychiatric and mental health services research communities for at least three decades. Data from both the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study ( 1 ) and the National Comorbidity Study ( 2 ) reveal an extremely high prevalence of co-occurring substance abuse among persons with serious psychiatric disorders. Comorbid substance abuse has been linked to numerous negative clinical and behavioral outcomes in this population ( 3 , 4 , 5 ). It has been implicated in exacerbating persons' risk of engaging in violence toward others ( 6 , 7 ) as well as being victims of crime themselves ( 8 ). Failure to comply with substance abuse treatment protocols can result in expulsion from various programs, and inability to maintain abstinence can lead to ejection from some residential programs and increase risk of homelessness ( 9 ).

Editor's Note: The late Steve Banks, a coauthor of this paper as well as an article on page 1454 and a brief report on page 1483, was afriend of the journal—both as a contributor and statistical reviewer. In his most genial way he helped many investigators solve problems in data analysis and express their results more clearly. He had an unusual ability to make complicated statistical concepts clear to those of us with less schooling or fuzzier understanding. He also developed some interesting applications for statistical methods, as in this article. We will miss him.

There is a tendency in much of the literature on substance abuse and mental illness to treat the use and abuse of alcohol and drugs as a single problem. Lumping the two practices together is not unreasonable; both are risk factors for many of the same undesirable outcomes, and many individuals with co-occurring disorders likely use both drugs and alcohol. But the negative consequences of illicit drug use are arguably greater. It is well known that significant drug use and especially maintaining a drug habit often requires interactions with persons and frequenting places with high rates of criminal activity and that users themselves must sometimes engage in illegal activities to support their drug use. The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that 83% of state and federal prison inmates surveyed in 1991 reported having used drugs at some point in their lives, and 32% reported being under the influence of drugs when they committed the offenses for which they were convicted ( 10 ).

Many factors may lead persons with serious mental illness to become involved with illicit substances. Environmental exposure to drug-related activity arguably plays a significant role for many in this population. One pathway to exposure may be linked with the poverty experienced by persons with serious mental illness, which forces them to reside in locales with high rates of criminal activity and, in particular, high rates of illicit drug activity ( 11 ). In such areas, as has been well documented, the social networks in which individuals participate may be ones in which pressure to buy and use drugs is high; also, in these areas persons receiving disability payments may be attractive and easy targets for drug dealers ( 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ).

An additional significant, though often overlooked, point in the discussion of drug involvement among persons with serious mental illness is that, unlike alcohol, the use of which by adults is legal, the mere possession of illicit drugs, even in small quantities, is by definition unlawful. Indeed, just knowingly being present where drugs are kept is grounds for arrest and prosecution in some jurisdictions, and convictions on charges beyond simple possession can carry draconian prison sentences as well as additional postincarceration penalties, such as exclusion from Section Eight housing ( 16 ), an important source of residential support for persons with serious mental illness, as well as loss of other benefits that may dramatically and negatively affect individuals' prospects for social integration and rehabilitation ( 17 , 18 ).

Despite the seriousness of the potential legal ramifications of arrests on drug charges, there has been little discussion of the legal implications of involvement with illicit drugs on the part of persons with mental illness. This article attempts to provide a starting point for such a discussion by addressing three questions. First, how common are drug-related arrests—that is, arrests specific to possession or other involvement with illicit drugs—among persons with serious mental illness? Second, are these arrests for simple possession or for more significant offenses that may incur greater sanctions and potentially more serious consequences? And finally, is the criminal justice involvement of persons arrested on drug charges confined just to those offenses or are drug charges part of a broader pattern of offending, as is often the case in the general population?

Addressing the first two questions sheds light on the nature and intensity of drug offending in a population already well known to be at high risk of substance abuse. The third question addresses whether drug offending in this population is associated with other kinds of criminal behaviors, as is often the case in the general population, or simply reflects some individuals' tendency to possess drugs or to be where they are present. This question is important in planning appropriate jail diversion and other services for persons arrested on these charges and for designing protocols aimed at helping persons with mental illness avoid even initial involvement with illicit drugs.

Methods

We examined data on a cohort of individuals age 18 years and older (N=13,816) receiving adult inpatient, residential, or case management services from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health during July 1991 through June 1992. Eligibility for these services was based on having a diagnosis of serious and persistent mental illness, a history of functional disability, and multiple psychiatric hospitalizations. Arrest data for cohort members spanning just less than ten years following the cohort's identification were obtained from the Massachusetts Criminal Offender Record Information (CORI) system. (A more complete overview of the cohort and its arrest patterns is available in a study by Fisher and colleagues [19].)

This project was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School and by the Central Office Research Review Committee of the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. Access to the CORI data was granted after review of the project by the Massachusetts Criminal History Systems Board, which oversees the use of those data.

Results

Patterns and prevalence of drug arrests

A total of 720 individuals, or 5% of the cohort (N=13,816), were arrested at least once (and in some cases numerous times) on a drug-related charge during the observation period, accumulating a total of 9,357 charges. The highest prevalence of drug-related arrests over the study period was observed among persons aged 18 to 25 years (15%) in the 12-month period during which the cohort was identified. Drug-related arrest rates for demographic subgroups are shown in Table 1 . As indicated, males were at higher risk of having a drug-related arrest than females. In addition, the rate for nonwhite cohort members (246 of 2,414, or 10.2%) was roughly two-and-a-half times that of white members (453 of 11,144, or 4.0%).

|

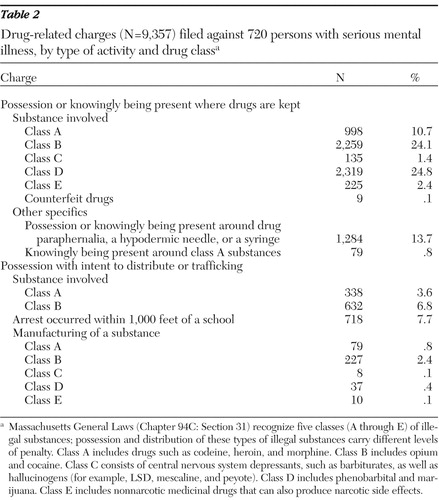

The charges associated with these drug arrests are summarized in Table 2 , along with explanations and legal classifications (based on Massachusetts law) of the types of drugs and activities involved. The majority of charges were for simple possession or knowingly being present where drugs were kept. However, roughly 20% of these charges reflected involvement with drug distribution or manufacturing. One possible indicator of the level of these individuals' involvement in actual "drug operations" is the prevalence of arrests on conspiracy charges. Although we cannot directly link the conspiracy charges to the drug charges, the fact that, of the 179 individuals who were facing a conspiracy charge, 147 (82%) also had a drug-related arrest seems telling. Furthermore, the statistical relationship between these arrest types was highly statistically significant (continuity-corrected χ2 =2,155.92, df=1, p<.001).

|

Other criminal charges among persons with drug arrests

Our data also show considerable criminal involvement apart from drug offenses among persons with drug-related arrests. Among those between the ages of 18 and 25 years with a drug arrest, roughly 98% (172 of 175 persons) had at least one arrest on a non-drug-related charge; for the total cohort this figure was 95% (684 of 720 persons). Twenty percent of these non-drug arrests (147 of 720 persons) were for conspiracy to commit a crime. This pattern is consistent with that observed in the general offending population. Using demographically adjusted data, we compared the prevalence of the "drug-arrest only" pattern observed in our cohort with that in Massachusetts's total arrestee population, using the CORI data for all offenders in the state. In this population the ten-year "drug-only" arrest prevalence for the same period was 3.0%.

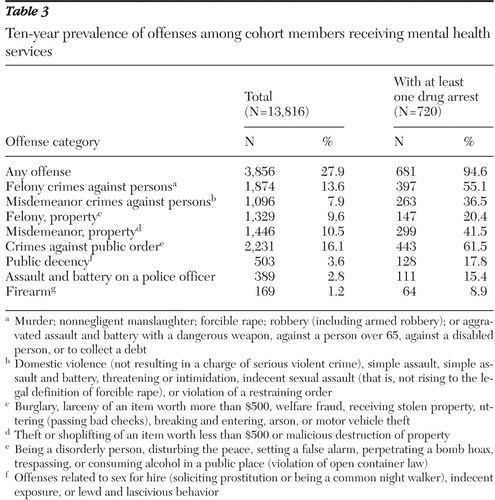

The percentage of drug offenders with at least one arrest in each of the various offense categories is shown in Table 3 , along with a summary of the specific types of charges contained within these categories. As these data show, the prevalence of arrest across various offense categories is substantially higher than in the cohort as a whole.

|

Crimes against persons, both felonies and misdemeanors, were particularly prominent; more than half of the individuals with drug-related arrests had been charged with a felony crime against a person. Just over 40% of individuals with at least one drug arrest were arrested for misdemeanor property crimes, which include thefts of items worth less than $500 as well as receiving and selling stolen property. In virtually every category the prevalence of non-drug-related arrests among those with drug-related arrests was at least double, and for one category (misdemeanor property crime) the rate was quadrupled.

Similarly, "sex offenses" (public decency charges), which, as indicated in the footnote to Table 3 , include prostitution and related offenses of the kind that might provide economic means for procuring drugs, were also elevated. Examination of arrest patterns among women suggests a strong relationship between having a sex crime charge (principally related to prostitution) and an arrest for a drug charge. Of the 161 women with at least one drug-related arrest, 52 (32%) also had at least one sex crime arrest. These 52 women accounted for 44% of the 118 arrested at least once for a sex-related offense over the ten-year period. The relationship between these offenses and drug-related arrests among women was strong and statistically significant (continuity-corrected χ2 =780.48, df=1, p<.001)

Discussion

Several factors must be considered in viewing these data. First, we should point out that we have not taken into account loss to follow-up, loss to mortality, or out-of-state arrests among cohort members in estimating rates of drug arrest. It is unclear what effects any of these factors might have on those estimates. We also emphasize that arrests reflect only actions taken by police officers in response to perceived violations of the law; they are neither findings of guilt nor convictions. It is also important to note that drug arrests are not an accurate reflection of the prevalence of drug use in this cohort or in similar populations. It is likely that many persons' drug use escapes the attention of police; likewise, some individuals may be present where drugs are kept or processed and, though not using them, be arrested if police believe they knew drugs were present. Finally, it is important to keep in mind that our cohort's members are persons whose psychiatric illnesses were severe and persistently disabling enough to meet the state's stringent eligibility criteria for receiving services. This point should be recalled when considering the generalizability of these data to the broader population of persons with serious psychiatric disorders who may be involved with illicit substances.

These data speak to three issues: drug possession, involvement with drug distribution or manufacture, and other patterns of offending. Many of the simple possession charges involve marijuana or other recreational drugs and may simply reflect either being in the "wrong place at the wrong time" or casual recreational use similar to that found in many segments of the population. These charges may carry only minor penalties, especially on a first offense (although in some jurisdictions even these minor drug crimes carry lengthy prison sentences). But as we noted earlier, arrests for simple possession of "harder" drugs can have significant legal and service-eligibility outcomes, and clientele of mental health agencies should be reminded of the problems that can arise from involvement with such substances.

Manufacturing and distributing reflect a much more consequential set of behavioral patterns. Convictions on these charges carry the harsh criminal penalties and postconviction denial of benefits described above. As we noted, roughly 20% of individuals with drug-related arrests also had arrests for conspiracy. Although we cannot be certain that these conspiracy arrests were drug related, the 20% figure corresponds roughly to the percentage of persons arrested on charges involving more than simple possession. If these are in fact related, they suggest a serious level of legal entanglement that can have profound problems for those arrestees.

Equally troubling is the strong relationship between drug-related arrests and arrests on other charges. As we noted, only about 5% of persons with drug-related arrests were charged solely with drug-related offenses over the observation period. This pattern is consistent with that observed in the general offending population, suggesting that among persons with serious mental illness, as in the general population, drug involvement may be embedded in a larger pattern of offending, a finding consistent with the Bureau of Justice Statistics data cited above ( 10 ).

What do these data tell us? The data on drug possession are essentially a reminder of the extent to which individuals with serious mental illness have opportunities for involvement with illicit drugs. The clustering of charges in the younger age cohorts suggests that these individuals may have peers who use drugs or frequent settings where drugs are easily obtained. As we noted, this should not come as a surprise, given the drug-infested environments in which some persons with mental illness reside and the lifestyle patterns these environments may induce ( 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ).

Whether the more serious charges observed here, involving manufacture and distribution, are simply an extension of these behaviors arrived at through the same pathways and resulting from the same risk factors is unclear. We might safely assume that these arrestees are not major drug dealers; it is more likely that they work as processors or as "mules," transporting drugs on behalf of dealers in exchange for drugs or cash. But given the serious consequences sometimes associated with convictions on these charges, additional research in this area might be profitable.

Because it deals with arrest patterns only, our data cannot help us in directly identifying risk factors for engaging in more serious drug offending. There are, however, descriptions of pathways to such behaviors (apart from simply using substances) in the literature that resonate with our understanding of the lifestyles of some persons with severe mental illness and which may help in contextualizing our findings.

Journalist Adrienne LeBlanc ( 20 ), in her accounts of life among young Puerto Ricans in the Bronx, describes a social environment occupied by persons who, like many persons with serious mental illness, are poor and socially disenfranchised. Many of the youths she observed became involved with the drugs and drug dealing pervading their neighborhoods; however, this involvement was not simply because of the attractions of the drugs themselves. As LeBlanc's account suggests, drug-related activities hold multiple attractions: large-scale drug dealers may have significant social status in their communities as well as enormous financial resources and the ability to convey numerous favors, including employment at wages that vastly exceed those obtainable through legal employment. (For persons with mental illness living on public assistance such wages will, of course, go unreported, boosting their "disposable income" while not affecting their entitlements.) In addition, the dealer's local operation, as LeBlanc described it, conveyed significant social standing to those involved with it. Importantly, LeBlanc's account also suggests that some persons working in this operation were themselves not drug users, and some, including many juveniles, were used as operatives because they would not be credible witnesses.

How might persons with serious mental illness come to be involved with such operations? Are they taken advantage of in these situations? Are they enticed by potential social and economic benefits? Are they viewed by drug dealers as "expendable" or seen as attractive employees because if apprehended they might not be regarded as credible prosecution witnesses? Addressing such questions takes us well beyond the scope of our data, but doing so is essential in framing efforts to help individuals understand both the attractions and the serious risks attending involvement with drugs and drug dealing.

Also disturbing is the 95% prevalence of non-drug-related arrests among persons charged with drug offenses, a rate nearly identical to that of drug arrestees in Massachusetts's general offending population over the same period. It would be tempting to infer that many of these arrests are associated with drug involvement. Indeed, it is virtually a given that persons who use drugs, particular those with serious addictions, engage in a variety of unlawful behaviors—including property crimes, crimes against persons, and prostitution—to support their drug use. However, our data cannot directly support the point that this pattern is the one that would be most commonly observed among the cohort members arrested on drug charges. Clearly, a next step in research in this area would be to determine where the drug arrests fit within a larger pattern of offending and what subpatterns are identifiable on the basis of temporal and other factors.

Conclusions

Our data lack the detail required to make definitive statements about the nature and etiology of drug-related behaviors. We would hope, however, that these findings would stimulate further research in this area. From the perspective of the mental health service system, it would be useful to understand how individuals with severe mental illness become involved in drug-related activities. If it has to do simply with drug use, then the legal ramifications of that behavior need to be made clear as part of substance abuse treatment protocols. Such protocols might include strategies for identifying and coping with the pressures of social networks as well as the predatory drug dealers operating within some neighborhoods. If it is the economic or social attractiveness of such involvement that lures these individuals, additional social skills training protocols might be developed that would help in resisting those attractions, making clear the risks of incarceration and other penalties and their potential effects on their lives. Indeed, although many persons with serious mental illness live a life marked by poverty, drug convictions can make their plights even worse ( 15 , 16 , 17 ). For interventions in these areas to be effective, however, they must take into account the demographic, cultural, and socioenvironmental characteristics of those at greatest risk and tailor clinical and social prevention strategies to those individuals ( 21 ). That said, the factors that increase exposure to illicit drugs—poverty, discrimination in housing choice, unstable housing, homelessness, lack of meaningful prosocial engagement—are part of a larger constellation of problems confronting persons with mental illness ( 10 ). Addressing those problems is a bigger challenge.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant RO1-MH-65615 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of their late colleague and dear friend Steve Banks, Ph.D., who passed away suddenly in August of this year. None of the work on this project could have been carried out without his enormously valuable contributions. Mental health services research has sustained a personal loss that will profoundly affect the work of an untold number of investigators for years to come.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Regier DS, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511–2518, 1990Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19, 1990Google Scholar

3. Drake RE, Wallach MA: Substance abuse among the chronically mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1041–1046, 1989Google Scholar

4. Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Blanchard JJ: Comorbidity of schizophrenia and substance abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:845–856, 1992Google Scholar

5. Owen RR, Fischer PJ, Both BM, et al: Medication noncompliance and substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:853–858, 1996Google Scholar

6. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393–401, 1998Google Scholar

7. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and non-adherence to medication. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:226–231, 1998Google Scholar

8. Sells DJ, Rowe M, Fisk D, et al: Violent victimization of persons with co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 54:1253–1257, 2003Google Scholar

9. RachBeisel J, Scott J, Dixon L: Co-occurring severe mental illness and substance use disorders: a review of recent research. Psychiatric Services 50:1427–1434, 1999Google Scholar

10. Flanagan TJ, Maguire K (eds): Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics 1991. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1992Google Scholar

11. Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, et al: Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:565–573, 2002Google Scholar

12. Alverson H, Alverson M, Drake RE: Social patterns of substance use among people with dual diagnoses. Mental Health Services Research 3:3–14, 2001Google Scholar

13. Drake RE, Wallach MA, McGovern MP: Future directions in preventing relapse to substance abuse among clients with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services 56:1297–1302, 2005Google Scholar

14. Rollins AL, O'Neill SJ, Davis KE, et al: Substance abuse relapse and factors associated with relapse in an inner-city sample of patients with dual diagnoses. Psychiatric Services 56:1274–1281, 2005Google Scholar

15. Fischer PJ: Criminal activity among the homeless: a study of arrests in Baltimore. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:46–51, 1988Google Scholar

16. Department of Housing and Urban Development: screening and eviction for drug abuse and other criminal activity: final rule: 24 CFR parts 5 et al. Federal Register 66:28776–28806, 2001Google Scholar

17. Blitz C, Wolff N, Pan K, et al: Mental Illness in prison and its impact on community residence post-release: implications for recovery and community integration. American Journal of Public Health 95:1741–1746, 2005Google Scholar

18. Pogorzelski W, Wolff N, Pan K, et al: Are second chances possible? The reality of public policy on reentry for ex-offenders with behavioral health problems. American Journal of Public Health 95:1718–1724, 2005Google Scholar

19. Fisher WH, Roy-Bujnowski K, Grudzinskas AJ, et al: Patterns and prevalence of arrest in a statewide cohort of mental health care consumers. Psychiatric Services 57:1623–1628, 2006Google Scholar

20. LeBlanc AN: Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble and Coming of Age in the Bronx. New York, Scribner, 2003Google Scholar

21. Goldman HH, Ganju V, Drake RE, et al: Policy implications for implementing evidence-based practices. Psychiatric Services 52:1591–1597, 2001Google Scholar