An Assessment of Beliefs About Mental Health Care Among Veterans Who Served in Iraq

The likelihood of military veterans having mental health symptoms increases postdeployment, particularly for those who have combat-related experiences ( 1 ). About a quarter of recent war veterans receiving care in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system have reported mental health problems ( 2 ). Soldiers returning from Iraq were more likely to meet criteria for depression, anxiety, or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than soldiers returning from Afghanistan ( 1 ). Rates of mental health symptoms for soldiers returning from Iraq were as high as 20% for PTSD, 18% for anxiety, and 15% for depression ( 1 ).

Given the prevalence of mental health concerns among returning veterans, it is critical to promote the detection and treatment of these disorders in this population. Unfortunately, many returning veterans struggling with such problems do not initiate treatment ( 1 ). This study was designed to explore factors that influence veterans' decisions to seek treatment for these disorders. A better understanding of the underlying determinants can provide the basis for interventions to encourage treatment seeking.

The conceptual framework for the study was provided by the theory of planned behavior ( 3 ), which has been used successfully to explain and predict health behaviors ( 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). Briefly, according to the theory, human action is guided by three considerations: beliefs about likely consequences of behavior (behavioral beliefs), beliefs about the normative expectations of others (normative beliefs), and beliefs about factors that facilitate or prevent performance of behavior (control beliefs). In their respective aggregates, behavioral beliefs produce a favorable or unfavorable attitude toward the behavior, normative beliefs result in perceived social pressure or subjective norm, and control beliefs give rise to perceived behavioral control—the perceived capability of performing the behavior. In combination, attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm, and perception of behavioral control lead to the formation of a behavioral intention. As a general rule, the more favorable the attitude and subjective norm and the greater the perceived control, the stronger should be the person's intention to perform the behavior in question. Finally, given a sufficient degree of actual control over the behavior, people are expected to carry out their intentions when the opportunity arises. Intention is thus assumed to be the immediate antecedent of behavior and to guide behavior in a controlled and deliberate fashion. However, because many behaviors pose difficulties of execution that may limit volitional control, it is useful to consider actual behavioral control in addition to intention.

According to the theory of planned behavior, the decision to engage in any behavior can ultimately be traced to the person's beliefs about that behavior. For the purpose of this study, we identified the behavior as seeking mental health treatment from a physician or mental health specialist for the treatment of mental health concerns within one year after returning from the war in Iraq. To obtain information about the behavioral, normative, and control beliefs common in the research population, we conducted elicitation interviews with key informants. In contrast to traditional qualitative interviews intended for open coding, elicitation interviews are designed to collect specific information about predetermined constructs identified by the theory of planned behavior. The beliefs identified in this manner can be used in future intervention programs. The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences and the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System Research and Development institutional review boards approved this study.

Methods

Army National Guard soldiers who served a one-year deployment in Operation Iraqi Freedom were enrolled during monthly drill weekends at local armories approximately one year after returning from war. This study took place between June and November 2006. Participants were given information about the study through the chain of command. Interested participants were asked to go through an informed consent process with research staff. Eligibility was determined through a structured diagnostic assessment for depression, panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, and alcohol abuse disorder with the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), a commonly used and validated structured psychiatric assessment instrument ( 9 ). Participants who screened positive for at least one of the targeted disorders were eligible to participate as key informants in the elicitation interviews.

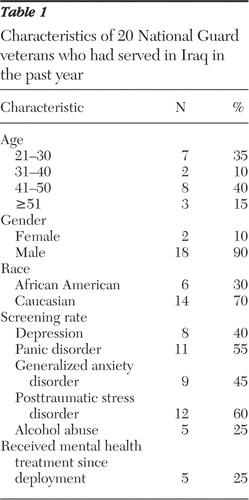

Thirty-five veterans were screened with the MINI, and 20 screened positive for one of the disorders. All 20 participated in the elicitation interviews.

Beliefs were elicited in open-ended, semistructured interviews designed to gather information about the decision to seek behavioral health care with the theory of planned behavior model. Interviews were conducted with individuals by phone and audiotaped. All interviews were conducted by the principal investigator (TS). Screenings were conducted by other research personnel. To elicit behavioral beliefs about seeking mental health treatment from a physician or mental health specialist to treat mental health concerns, participants were asked to describe any advantages or disadvantages that may occur from participating in mental health care. To elicit normative beliefs, participants were asked to describe any people, groups, or organizations that support or discourage the use of mental health care. To elicit control beliefs, participants were asked to identify any factor that facilitates or impedes plans to initiate mental health care.

Interviews were transcribed and coded for each interviewee. Transcriptions were checked for completeness and accuracy. Three reviewers analyzed the content to identify commonly held beliefs in the research population. Coding occurred on a line-by-line basis in the text to increase the likelihood that each theme would be captured. Coders identified beliefs by using multiple strategies, including searching the text for main ideas, listening to stories, putting themes together, identifying repetition among respondents, looking for opposite themes, and searching for confirming and disconfirming evidence of themes. Using the theory of planned behavior model as a guide, coders identified and coded each belief. A coding sheet was designed on the basis of responses for each of the three key constructs. Similar beliefs were grouped together to increase specificity to the theory. To increase confidence that all instances of commonly held beliefs were identified, coders read and marked codes independently before meeting jointly to discuss themes for consensus.

Results

Characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1 .

|

Getting better was reported by 16 of 20 (80%) of informants as the primary advantage of seeking mental health care. Most statements focused on the need for symptom improvement, especially for sleep and relationships. "I can't sleep anymore. Over there, going to bed could get you killed."

Half of the sample reported that being able to talk to someone who would understand their symptoms was a primary advantage of treatment. One informant reported, "You can't get a shot for these problems—or a pill. You need time to process it."

Another six participants (30%) talked about treatment as a means to return to "normal," although this concept was expressed in multiple ways. Some reported a desire to be able to concentrate and perform at work. Others wanted to be released from traumatic memories: "I can deal with PTSD as long as it is not every time I walk in the door, drive down the road, or sit in my chair. You know every TV show has something that triggers something. It could be my wife in there cooking and I get the smell of brains. Everything now triggers something for me in Iraq."

The primary disadvantage of receiving mental health care was stigma. Stigma was identified both in terms of the label received for being "crazy" and the consequences to participants' military career. A total of 14 participants (70%) reported a fear of being labeled, and 11 (55%) discussed consequences to work. High-ranking officers who participated in interviews reported that seeking care could affect perceptions of their leadership abilities and result in deaths among those they lead, whereas lower-ranking individuals reported fears of becoming nondeployable or not being able to receive promotions. "I would not want anyone ranked below me to know that I had mental health problems. They would think that I am not capable of performing my duties, and this doubt could get them killed. They need to believe that I am right in the head."

Getting immediate help was also perceived as interfering with their return home. "When we came back from our deployment, we had to go through all these little classes, and some of those were mental health classes. Without a doubt, we knew that everybody was there to help us. The last thing on our mind was wanting that help. We wanted to go home."

Most informants (15, or 75%) indicated that everyone would support their decision to seek care. For example, one veteran stated, "I'm 32 years old. Who am I going to get in trouble by? The only people I have to answer to are God and my wife." Another stated, "It is not a stigma. That is what you have to remember. If you go and get help, it is not a stigma. It is like there is no such thing as a stupid question, because you are trying to learn something. It is just like if you have a toothache, you go to the dentist." The other 25% (N=5) reported that various members of their family would rather they "suck it up" and not identify themselves as needing help.

A majority of participants (15, or 75%) stated that the military would support their choice to seek care. In fact, several informants stated that the "entire [brigade] would support" their choice to seek care. However, this belief was not universal. One informant stated, "There were officers and key non-commissioned officers that encouraged soldiers not to say everything they needed to say [on the postdeployment health assessment], and they would say 'Boy, if you do this and you do that, it is going to come back and haunt you.' "

In terms of facilitators, respondents reported that they would prefer treatment to be nonthreatening. By this they indicated that they required confidentiality and would prefer a convenient, comfortable, nonclinical setting to receive care. "In going into a clinical environment, where you are going to talk about things that hurt your heart and that cause you great grief and distress, not only do you not know the counselor that you are going to talk to, but you are walking into a sterile environment that is foreign to you."

Of interest, the most commonly reported barrier to care was the way participants perceived care. In fact, 13 respondents (65%) stated that their own belief that they "ought to handle it on my own" or "didn't want to believe I had a problem" prevented their seeking treatment. One respondent reported, "The job I was doing, it didn't seem stressful at the time. It is coming back and looking back at everything I had to put up with. That is really stressful." Another stated, "It is like going to the dentist, you know what is on the other side of the door. You know there is pain in there, and so you associate mental care with medicine, plus seeing somebody that you don't really know."

Getting time off from work was the second most common barrier to care and was reported by seven respondents (35%).

Discussion and conclusions

Several key points should be emphasized. Although not designed as an epidemiologic study, this study showed that more than half of the respondents screened positive for mental health problems. Although the prevalence of mental health disorders is high among returning war veterans, the likelihood of seeking help for them is alarmingly low ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ). Even among recent veterans who acknowledged having mental health symptoms, less than half reported an interest in receiving help, and only a quarter actually got help ( 10 ). In this study, only 25% of the participants who screened positive for mental health problems had received formal treatment by the time they were interviewed, consistent with other studies ( 1 ).

Low rates of treatment seeking occurred despite the availability of mental health care programs for returning soldiers. All returning veterans are eligible for free VA care for two years after deployment, and the Department of Defense (DoD) and the VA have instituted a seamless transition so that returning soldiers can begin receiving care from the VA as smoothly as possible, with a minimum of paperwork requirements and other delays. The VA also has clinical reminders in place for veterans returning from Afghanistan and Iraq to promote screening for mental health disorders. The DoD offers programs on PTSD, and soldiers had access to "combat stress teams" while in country. DoD has collaborated closely with the VA on outreach efforts to returning soldiers. It should be noted that it is perhaps because of the seamless transition and local efforts that few veterans identified access barriers in the elicitation interviews. Consequently, none of the key informants raised concerns about access to care.

Our findings suggest that a preference for and access to treatment are not enough to motivate an individual to seek treatment. Results provide valuable information about reasons for low rates of help seeking and suggest ways to design effective interventions. Developing interventions to increase help seeking is crucial to providing treatment to veterans early in their treatment episode. Interventions that target cognitive beliefs in order to change behavior, such as those used in cognitive-behavioral therapies, may be ideal. Specifically, to be effective, interventions should emphasize advantages of treatment in terms of alleviating sleep disorders, improving relationships, and generally "returning to normal." They should counter the perceived stigma associated with mental health treatment as well as the belief that seeking treatment interferes with returning home. As to control, interventions should emphasize convenience and counter perceptions that soldiers should be able to deal with mental health problems on their own. Although participants who screened positive for mental health problems generally believed others supported help seeking, they also reported that a perceived stigma or label would be assigned to them if they sought help. It is possible that individuals have contradictory beliefs about mental health treatment seeking or that they were reporting on a different set of individuals. It is also possible that an individual can be supported for treatment seeking yet still labeled. Interventions may want to focus on this apparent contradiction.

Our findings are limited because interviews were conducted in one National Guard unit and may not generalize to others who serve in the military. Another limitation is that important nonverbal cues may have been missed because interviews were conducted by phone, although this may have made it easier for informants to explore beliefs in relative anonymity. We did not ask informants about perceptions of care received at the VA. Although the theory of planned behavior is a well-validated behavioral model, the legitimacy of our findings is dependent on the applicability of this model to the treatment-seeking behavior of veterans.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant QUERI PPR 06-148 from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al: Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine 351:13–22, 2004Google Scholar

2. Kang HK, Hyams KC: Mental health care needs among recent war veterans. New England Journal of Medicine 352:1289, 2005Google Scholar

3. Ajzen I: The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50:179–211, 1991Google Scholar

4. Hardeman W, Johnston M, Johnston D, et al: Application of the theory of planned behaviour in behaviour change interventions: a systematic review. Psychology and Health 17:123–158, 2002Google Scholar

5. Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT: Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African American adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 279:1529–1536, 1998Google Scholar

6. Murphy WG, Brubaker RG: Effects of a brief theory-based intervention on the practice of testicular self-examination by high school males. Journal of School Health 60:459–462, 1990Google Scholar

7. Brubaker RG, Fowler C: Encouraging college males to perform testicular self-examination: evaluation of a persuasive message based on the revised theory of reasoned action. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 20:1411–1422, 1990Google Scholar

8. Conner M, Sparks P: Theory of planned behaviour and health behaviour, in Predicting Health Behaviour: Research and Practice With Social Cognition Models. Buckingham, England, Open University Press, 2005Google Scholar

9. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59:22–33, 1998Google Scholar

10. Von Korff M, Simon G: The prevalence and impact of psychological disorders in primary care: HMO research needed to improve care. HMO Practice 10:150–155, 1996Google Scholar

11. Hollon SD, Thase ME, Markowitz JC: Treatment and prevention of depression. Psychological Science in the Public Interest 3:39–77, 2002Google Scholar

12. Merrill KA, Tolbert VE, Wade WA: Effectiveness of cognitive therapy for depression in a community mental health center: a benchmarking study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71:404–409, 2003Google Scholar

13. Nierenberg AA, Petersen TJ, Alpert JE: Prevention of relapse and recurrence in depression: the role of long-term pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:13–17, 2003Google Scholar

14. Powers RH, Kniesner TJ, Croghan TW: Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in depression. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 5:153–161, 2004Google Scholar