A Comparison of Assertive Community Treatment and Intensive Case Management for Patients in Rural Areas

Persons with severe mental illness in rural areas are often disadvantaged because of a lack of adequate services and professional staffing shortages ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). Rural mental health providers must structure services to accommodate many diversely populated and dispersed communities that lack specialized personnel and whose residents face long travel time and other costs in accessing centrally located services ( 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ). Mental health professionals have reported difficulties in adapting existing urban-based treatments to rural communities, and very little research is available on evidence-based practices in rural areas to guide them ( 9 ). The goal of this review article is to compare and contrast the evidence for two popular service delivery models, assertive community treatment and intensive case management, in rural areas.

The assertive community treatment model uses a large, multidisciplinary staffed team with shared caseloads to provide a full range of direct services to consumers ( 10 ). Assertive community treatment is one of the most researched interventions in the United States and elsewhere ( 11 , 12 , 13 ). Also, assertive community treatment is part of the Implementing Evidence-Based Practices project ( 10 ), an effort to broaden the dissemination of evidence-based mental health treatments across the nation. In order to encourage more widespread dissemination of assertive community treatment, states such as Indiana and New York are using Medicaid reimbursements as an incentive for statewide expansion to rural areas ( 14 , 15 ). These efforts have yet to demonstrate, however, that assertive community treatment services can be sustained in rural settings.

Assertive community treatment is designed as a self-contained multidisciplinary treatment team that spends more than 75% of staff time in the field providing direct services to consumers. Since its development in Madison, Wisconsin, in the early 1970s, assertive community treatment has been disseminated across the nation and overseas ( 16 ). As assertive community treatment programs have spread into rural areas, programs have struggled to meet the challenges of implementing and maintaining high-intensity services. Rural programs have had to adapt the model to accommodate the common barriers of low population density, staff shortages, and the stigma of psychiatric illness. Such adaptations have led to wide variability, although some programs have retained the "assertive community treatment" label even when there have been dramatic modifications to and departures from assertive community treatment fidelity standards.

Intensive case management encompasses a range of service delivery practices that are less intensive and not as standardized as the assertive community treatment model ( 17 , 18 , 19 ). Intensive case management involves assertive outreach, assessment of consumer need, and negotiation and coordination of care. In one large-scale implementation started in 1992, the state of New York supported intensive case management with a capitated Medicaid financing strategy ( 19 , 20 ). Since then, intensive case management has been implemented at different sites across the United States, including an adaptation at the Department of Veterans Affairs ( 21 ), as well as in Europe ( 22 ) and Australia ( 23 ). However, there is little information about the implementation or adaptation of the intensive case management model in rural areas of the United States ( 24 ).

This article addresses the following questions in an effort to assess the evidence base for the effectiveness of these two service models in rural areas. First, can rural assertive community treatment programs achieve the same outcomes and results as full-fidelity assertive community treatment programs in urban areas? Second, is there an evidence base to support assertive community treatment-"lite" programs, such as intensive case management, in rural areas, and can these programs produce outcomes similar to full-fidelity assertive community treatment?

Methods

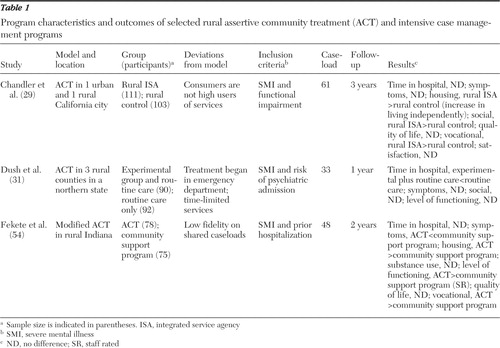

Recognizing that the name "assertive community treatment" itself was not sufficient to identify all relevant published studies, we developed a search strategy to identify relevant studies that was based on three program model criteria derived from prior literature reviews and implementation studies conducted in the United States ( 10 , 17 , 25 , 26 , 27 ): team members had shared caseloads, most services were delivered directly rather than brokered to other community resources, and a psychiatrist or nurses were regular members of the team. Using this strategy, we searched the PsycINFO and PubMed Central databases from 1973 to 2005 and located six studies that met the criteria ( 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ). Although these studies represented a wide variety of settings and implementation strategies for rural assertive community treatment, we sought to present the strongest evidence about program effectiveness, so we selected only the studies that used a true experimental design. Two controlled studies of rural assertive community treatment programs ( Table 1 ) met all of the above criteria ( 29 , 31 ). These studies are described in detail below.

|

In order to identify the evidence base for intensive case management, we used three core criteria to identify studies of intensive case management that were conducted in rural areas of the United States: individual caseloads, small caseload ratios of no more than one staff person to 15 consumers, and brokered services of negotiation and coordination of care in the community ( 17 , 18 , 19 , 34 ).

Using these criteria, we identified three studies of rural intensive case management ( 35 , 36 , 37 ), and we added one study ( 38 ) that could be described as assertive community treatment that did not meet our assertive community treatment criteria. As before, we selected only the studies that used a true experimental design. Only one study met all of the criteria ( 38 ) ( Table 1 ).

Results and discussion

Randomized trials of assertive community treatment

In 1988, California created two integrated service agencies that combined assertive community treatment with a capitated model of funding ( 39 ). Unlike the full-fidelity model, these programs specifically targeted a cross-section of persons with severe mental illness rather than focusing exclusively on high service utilizers ( Table 1 ). One program was located in a large city, and the other was located in a midsized city in an agricultural county described as rural ( 40 ). In a three-year randomized study, Chandler and colleagues ( 29 ) compared outcomes from both of these programs with outcomes from usual clinical mental health services with limited case management and rehabilitation services. The integrated service agencies had staff-to-client ratios of one to ten, provided round-the-clock services, and provided integrated direct services by the team. Unfortunately, the article by Chandler and colleagues ( 29 ) presented limited information about the team's structure except that both integrated service agencies (rural and urban) appeared to be fully staffed teams that included service coordinators, social workers, nurses, vocational specialists, substance abuse specialists, and psychiatrists ( 29 , 39 , 40 , 41 ).

Study findings showed no significant differences in average annual days hospitalized between the 46 patients in the rural assertive community treatment program (mean±SD of 28±62 days) and the 49 patients in the comparison group (34±70 days) ( 29 ). However, the rate of hospitalization was significantly lower in the first two years for the rural assertive community treatment program (baseline, 42%; year 1, 22%; χ2 =5.7, df=1, p=.017 versus baseline; year 2, 19%; χ2 =5.2, df=1, p=.023 versus baseline). In comparison with usual services, there were no significant differences favoring the rural assertive community treatment team with regard to symptoms, rates of arrest, medication compliance, homelessness, or criminal victimization.

In addition, no significant differences in consumer outcomes were noted between the urban and rural program sites, which suggests that fully staffed assertive community treatment teams in rural and urban areas can produce similar results. At the end of the study, the researchers concluded that the costs for the state of California were too high to implement this type of assertive community treatment in the public mental health system except for consumers (both urban and rural) who were high service users ( 29 ).

The second randomized trial of assertive community treatment in a rural setting used a transitional model of acute care for a group of persons in a local general hospital emergency department at risk of psychiatric hospitalization. Dush and colleagues ( 31 ) screened all persons at risk for hospitalization, except those already well connected to the local community mental health centers and existing assertive community treatment programs. The transitional team provided services until the consumer could be seen at a local mental health center. Participants who were randomly assigned to routine care had access to hospitals, follow-up appointments with a psychiatrist, and referral to the local community mental health center. The transitional team included a staff of six people with different backgrounds, including a clinical psychologist, a master's-level psychologist, two consulting psychiatrists, a psychiatric nurse, two psychology graduate students, and several home health aides. The program had one major deviation from the assertive community treatment model—it provided only time-limited services. Despite this significant deviation from the assertive community treatment model, this study illustrated some of the modifications rural communities have made and the outcomes associated with those modifications.

Study findings showed that the 90 participants who were randomly assigned to the transitional team had fewer total days of hospitalization than the 92 participants assigned to usual care (transitional team, 7.57±9.42 days; routine care, 10.39±10.44 days, F=5.33, df=3 and 178, p=.002). No significant differences were found in symptoms, level of functioning, or social support ( 31 ). These findings parallel those obtained by most assertive community treatment teams in urban areas—that is, reduced hospitalizations but no consistent effects on psychosocial outcomes ( 25 , 42 ).

Results from only two studies provide a limited evidence base for rural assertive community treatment. Both studies reported some decrease in hospitalization outcomes when the model was implemented with fully staffed treatment teams. These studies encompassed only a very small segment of the rural population and varied in their target populations, fidelity to the treatment model, and outcome measures. Both programs targeted persons with severe mental illness, but only one program targeted persons who were high service users or at risk of admission to a psychiatric hospital ( 31 ). The quality of implementation and documentation of fidelity to the assertive community treatment model also varied between studies. The most significant modification to the model was time-limited services ( 31 ).

Another problem affecting both studies was the use of reduced rates of hospitalization as a measure of program effectiveness. This clearly was accepted as a universal criterion in the early 1970s when the model was first developed, but today the use of inpatient hospitalization varies widely from state to state depending on the organization of the state public mental health system and the availability of community alternatives.

The assertive community treatment model in rural areas

In principle, assertive community treatment would seem to have several advantages for rural communities. The full-fidelity model consists of a self-contained multidisciplinary team of professionals, including a nurse, psychiatrist, vocational specialist, and substance abuse specialist, who collectively provide a wealth of clinical expertise and are able to individualize treatment. Working as a team also allows staff to be more mobile and to deliver services door to door rather than requiring consumers to travel long distances, thereby making treatment more accessible and affordable. Staff on the team benefit from reduced isolation and increased peer support, given that isolation is another common problem reported in the recruitment and retention of staff in rural areas ( 43 ).

The implementation of assertive community treatment in rural areas has not been without problems, however. A recent statewide survey of assertive community treatment programs in North Carolina illustrated the kinds of implementation problems that arise in dissemination of the assertive community treatment model to rural settings ( 44 ). Forty teams were identified in the state (19 in rural settings, 11 teams in a mixed rural and urban setting, and ten teams in urban settings) and compared on structural and process dimensions of the assertive community treatment model. The rural teams were very similar to the urban teams on process dimensions of the model, admission criteria, intake rate, treatment responsibility, team approach, and team meetings, but the teams differed on structural components. Rural teams were smaller in numbers of staff and consumers, and urban teams were more likely to have and maintain multidisciplinary staff, including vocational and substance abuse counselors.

Difficulties with staffing the assertive community treatment teams with specialized professionals are not uncommon in rural areas ( 9 ). Similar findings were recorded in the statewide implementation of assertive community treatment in Illinois, where staffing a team of professionals in rural areas was a problem ( 45 ). These findings reflect the common barriers in rural areas, especially personnel shortages, low population density, and limited and less accessible resources ( 8 ). They also demonstrate the difficulties in achieving uniform statewide implementation of assertive community treatment in both urban and rural areas.

Assertive community treatment is becoming one of the most widely accepted treatments across the nation, and it has influenced public policy ( 46 ). In response to overwhelming public and research support for assertive community treatment, states are rewriting Medicaid service definitions to be more compatible with assertive community treatment. In the process, these states have had to formulate standards for assertive community treatment teams for quality assurance, implementation, and reimbursement purposes. These fidelity-like standards have been put in place for all assertive community treatment teams in the state, with adjustments made for rural teams ( 14 , 15 ). The research literature on rural assertive community treatment programs, however, does not present clear guidelines on the standard structure and process dimensions associated with successful consumer outcomes.

Several studies of assertive community treatment have stressed that fidelity to the model leads to better consumer outcomes ( 26 , 47 , 48 , 49 ). Specifically, shared caseloads, daily team meetings, nurse participation, total number of contacts, and 24-hour availability have been linked to reductions in hospitalization ( 26 ). Assertive community treatment implementation across the full range of rural areas will most likely require additional changes to the model, such as creating smaller assertive community treatment teams to accommodate small and dispersed populations ( 9 ). As rural assertive community treatment programs reduce their staff sizes ( 32 , 50 ), they devolve to be more like intensive case management than full-fidelity assertive community treatment. Reducing the size of the assertive community treatment team in a rural area does not guarantee the same outcomes as found with a fully staffed high-fidelity team.

Intensive case management as an alternative model

Intensive case management is a brokered service delivery model designed to help persons with severe mental illness improve their integration within the community by linking them with treatment providers ( 18 , 51 ). Intensive case management was designed for persons with severe mental illness who are either high service users or not using traditional mental health services at all ( 19 , 34 ). Viewed by some as an adaptation of the assertive community treatment model, intensive case management combines the principles of case management (that is, assessment, planning, linking to services, monitoring, and advocacy) ( 52 ) with a low staff-to-consumer ratio, assertive outreach, and direct delivery of services ( 17 , 18 , 51 , 53 , 54 ).

There are two primary differences that distinguish intensive case management and assertive community treatment. First, case managers are responsible for individual caseloads, whereas assertive community treatment requires a multidisciplinary team with shared caseloads. Second, case managers broker services by linking and coordinating services for consumers, whereas each staff member of an assertive community treatment team provides direct services to consumers ( 18 ).

Intensive case management, however, lacks a manualized and validated program model that specifies necessary ingredients to ensure faithful program implementation ( 17 , 18 ). Instead, individual programs have had to develop their own approaches ( 19 ).

Below we summarize findings from one study of rural intensive case management that we found in our literature review. In a study described as rural assertive community treatment by Fekete and colleagues ( 38 ), four teams with two case managers on each team followed 78 consumers. They compared outcomes with those of 75 consumers receiving usual services in a community support program with much larger caseload sizes, which ranged from 30 to 60 consumers ( 55 ). (This study was not included in the assertive community treatment review because the team did not have a nurse or psychiatrist as part of the team.) The case managers had low staff-to-consumer ratios (one to ten), targeted high service users, provided services directly, and offered time-unlimited services. Although the case managers were instructed to use a team approach, the programs scored very low on fidelity items measuring shared caseloads.

In an earlier article from the same research team that was published after the first year of the study, McDonel and colleagues ( 55 ) concluded that the rural team had significant problems in implementation, including too little training for case managers, administrators who were not clear about the intensity and structure of the new treatment, and isolation from the other staff at the community mental health centers that made it difficult for staff to coordinate services. At the end of 24 months, staff rated consumers on the team higher on quality of life using a modified version of the Life Satisfaction Checklist with a 3-point scale ranging from 1, terrible, to 3, delighted (treatment, 2.32±.31; control, 2.13±.38; t=3.85 [df not available], p<.01; effect size=.71). Consumers were rated as having less severe symptoms on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (treatment, 1.63±.53; control, 1.87±.69; t=2.12 [df not available], p<.05; effect size=.41), with scores ranging from 1, not present, to 7, extremely severe. There were no differences in hospitalization outcomes, legal outcomes, or vocational functioning. In addition, the control group had more residential stability (most days in residence) than those in the treatment group (treatment, 289.8±87.5 days; control, 321.2±70.1 days; t=2.21 [df not available], p<.05; effect size=.39) ( 38 ).

With only one controlled study of intensive case management in a rural area, there was not enough evidence to adequately evaluate the effectiveness of this model in a rural setting. Previous reviews of intensive case management in urban settings have found that intensive case management can have a positive impact on mental health outcomes, but the results are mixed across studies ( 42 , 56 , 57 ). In general, intensive case management programs have been as effective as assertive community treatment models in improving social functioning, psychiatric symptoms, and quality of life but less successful in reducing admissions to the hospital ( 42 , 58 ).

One reason for the inconsistency of results across intensive case management programs may be the context in which the model is implemented. Researchers have suggested that the outcomes in case management are related to differences in the treatment model, characteristics of the population being treated, and characteristics of the service system, including availability of services ( 56 ). Because it is a brokered model within an existing system, intensive case management is effective only if it functions in a relatively service-rich environment. In fact when intensive case management programs have not reported significant reductions in hospitalizations, researchers have suggested that the community did not have sufficient services available for case managers to help consumers avoid hospitalization ( 59 ).

Assertive community treatment teams provide direct services to consumers, thereby reducing the need for additional treatment providers. However, a community with few resources also can limit the ability of these teams to access necessary services such as food banks or housing as well as to find jobs for consumers who are using supported employment services ( 56 ).

The paradox of treatment models for rural areas

Rural settings are characterized by limited mental health services and staff shortages—an environment in which a self-contained treatment team such as assertive community treatment would seem to make an ideal match. However, the logistics of serving a low-density population in combination with professional shortages make it difficult to situate full-fidelity assertive community treatment teams in rural areas. Rural communities often lack specialty services, such as residential and vocational alternatives, and they typically have only a few treatment providers ( 1 , 60 ).

The latter constraints suggest that intensive case management with its individual caseloads and fewer staff might be a substitute for assertive community treatment in many rural settings. Paradoxically, the current evidence base suggests that intensive case management is effective for persons with severe mental illness only when there are sufficient services in the area so that case managers can link consumers to them. In other words, intensive case management is not a stand-alone service. Its effectiveness depends on having other providers available to serve consumers. Ultimately the lack of resources in rural areas becomes both a barrier to service delivery and to the implementation of high-fidelity programs.

In reality there is a dual paradox—only weak evidence is currently available to suggest how assertive community treatment teams can be scaled down in rural areas to assertive community treatment-"lite" services that retain the effectiveness of the full-fidelity model. Studies have never been done to dismantle the components of the model to determine which elements of assertive community treatment are efficacious and the minimal practice pattern for sustaining these effects. The assertive community treatment label has been disseminated much more rapidly than has its faithful practice. Future studies that systematically vary key components of the assertive community treatment model need to be done to demonstrate the effectiveness of modified assertive community treatment teams in rural settings ( 26 ).

Conclusions

Rural mental health services are an important part of many state mental health systems, but rural settings face unique challenges in service delivery. Assertive community treatment programs in rural areas often make adjustments to accommodate resource constraints—such as deploying smaller teams, forming teams with a smaller range of specialized skills, and providing less intensive services—but there is little evidence that these adaptations will produce desired outcomes. Although many states have supported assertive community treatment in rural areas, current research does not provide adequate guidelines about the minimum staffing requirements (both number and type) or essential program components beyond which positive outcomes disappear.

Intensive case management uses some of the same principles as assertive community treatment, and in some circumstances it may be an alternative to rural assertive community treatment. But here again, more rigorous evaluation is needed to demonstrate its effectiveness in a range of rural settings.

Today the many natural experiments with assertive community treatment and intensive case management that are occurring across rural America provide opportunities to expand the evidence base that concerns what works in rural mental health service delivery for persons with severe mental illness. Hopefully, as state administrators respond to the report of the New Freedom Commission ( 61 ), they will recognize these gaps and work with the research community to develop stronger evidence-based practices for rural settings.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported in part by Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award MH-019117 to the University of North Carolina for postdoctoral research training in mental health services and systems.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Kane CF, Ennis JM: Health care reform and rural mental health: severe mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 32:445-462, 1996Google Scholar

2. Merwin E, Hinton I, Dembling B, et al: Shortages of rural mental health professionals. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 17:42-51, 2003Google Scholar

3. Rohland BM, Rohrer JE: Capacity of rural community mental health centers to treat serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 34:261-273, 1998Google Scholar

4. Sullivan G, Jackson CA, Spritzer KL: Characteristics and service use of seriously mentally ill persons living in rural areas. Psychiatric Services 47:57-61, 1996Google Scholar

5. Blank MB, Fox JC, Hargrove DS, et al: Critical issues in reforming rural mental health service delivery. Community Mental Health Journal 31:511-524, 1995Google Scholar

6. Fox J, Merwin E, Blank M: De facto mental health services in the rural south. Journal of Health Care of the Poor and Underserved 6:434-468, 1995Google Scholar

7. Human J, Wasem C: Rural mental health in America. American Psychologist 46:232-239, 1991Google Scholar

8. Philo C, Parr H, Burns N: Rural madness: a geographical reading and critique of the rural mental health literature. Journal of Rural Studies 19:259-281, 2003Google Scholar

9. Judd F, Fraser C, Grigg M, et al: Rural psychiatry—special issues and models of service delivery. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 10:771-781, 2002Google Scholar

10. McGrew JH, Bond GR: Critical ingredients of assertive community treatment: judgments of the experts. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:113-125, 1995Google Scholar

11. Burns BJ, Santos AB: Assertive community treatment: an update of randomized trials. Psychiatric Services 46:669-675, 1995Google Scholar

12. Dixon L: Assertive community treatment: twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatric Services 51:759-765, 2000Google Scholar

13. Marshall M, Lockwood A: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental disorders (Cochrane Review), in The Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK, Wiley, 2004Google Scholar

14. Assertive Community Treatment Teams Certification. Indiana Administrative Code, Article 5.2, 2003Google Scholar

15. Assertive Community Treatment: Program Guidelines. New York, New York State Office of Mental Health, 2002Google Scholar

16. Dixon LB, Goldman HH: Forty years of progress in community mental health: the role of evidence-based practices. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 37:668-673, 2003Google Scholar

17. Schaedle RW, Epstein I: Specifying intensive case management: a multiple perspective approach. Mental Health Services Research 2:95-105, 2000Google Scholar

18. Schaedle R, McGrew JH, Bond GR, et al: A comparison of experts' perspectives on assertive community treatment and intensive case management. Psychiatric Services 53:207-210, 2002Google Scholar

19. Surles RC, Blanch AK, Shern DL, et al: Case management as a strategy for systems change. Health Affairs 11(1):151-163, 1992Google Scholar

20. Shern DL, Surles RC, Waizer J: Designing community treatment systems for the most seriously mentally ill: a state administrative perspective. Journal of Social Issues 45:105-117, 1989Google Scholar

21. Rosenheck RA, Neale MS, Leaf P, et al: Multisite experimental cost study of intensive psychiatric community care. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:129-140, 1995Google Scholar

22. Aberg Wistedt A, Cressell T, Lidberg Y, et al: Two-year outcome of team-based intensive case management for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 46:1263-1266, 1995Google Scholar

23. Issakidis C, Sanderson K, Teesson M, et al: Intensive case management in Australia: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 99:360-367, 1999Google Scholar

24. Godley SH: A Treatment System United for Persons With Mental Illness and Substance Abuse: The Illinois MI/SA Project. Bloomington, Ill, Lighthouse Institute, Chestnut Health Systems, 1995Google Scholar

25. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: Assertive community treatment for people with severe mental illness: critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 9:141-159, 2001Google Scholar

26. McGrew JH, Bond GR, Dietzen L, et al: Measuring the fidelity of implementation of a mental health program model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 62:670-678, 1994Google Scholar

27. McGrew JH, Pescosolido B, Wright E: Case managers' perspectives on critical ingredients of assertive community treatment and on its implementation. Psychiatric Services 54:370-376, 2003Google Scholar

28. Becker RE, Meisler N, Stormer G, et al: Employment outcomes for clients with severe mental illness in a PACT model replication. Psychiatric Services 50:104-106, 1999Google Scholar

29. Chandler D, Meisel J, Hu TW, et al: Client outcomes in a three-year controlled study of an integrated service agency model. Psychiatric Services 47:1337-1343, 1996Google Scholar

30. Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Noordsy DL: Treatment of alcoholism among schizophrenic outpatients: 4-year outcomes. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:328-329, 1993Google Scholar

31. Dush DM, Ayres SY, Curtis C, et al: Reducing psychiatric hospital use of the rural poor through intensive transitional acute care. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 25:28-34, 2001Google Scholar

32. Kane CF, Blank MB: NPACT: enhancing programs of assertive community treatment for the seriously mentally ill. Community Mental Health Journal 40:549-559, 2004Google Scholar

33. Santos AB, Hawkins GD, Julius B, et al: A pilot study of assertive community treatment for patients with chronic psychotic disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:501-504, 1993Google Scholar

34. Repper J, Ford R, Cooke A: How can nurses build trusting relationships with people who have severe and long-term mental health problems? Experiences of case managers and their clients. Journal of Advanced Nursing 19:1096-1104, 1994Google Scholar

35. Godley SH, Finch M, Dougan L, et al: Case management for dually diagnosed individuals involved in the criminal justice system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 18:137-148, 2000Google Scholar

36. Husted J, Wentler SA, Bursell A: The effectiveness of community support programs for persistently mentally ill in rural areas. Community Mental Health Journal 30:595-600, 1994Google Scholar

37. Husted J, Wentler S, Allen G, et al: The effectiveness of community support programs in rural Minnesota: a ten-year longitudinal study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:69-72, 2000Google Scholar

38. Fekete DM, Bond GR, McDonel EC, et al: Rural assertive community treatment: a field experiment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 21:371-379, 1998Google Scholar

39. Hargreaves WA: A capitation model for providing mental health services in California. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:275-279, 1992Google Scholar

40. Chandler D, Meisel J, Hu T, et al: A capitated model for a cross-section of severely mentally ill clients: hospitalization. Community Mental Health Journal 34:13-26, 1998Google Scholar

41. Chandler D, Meisel J, McGowen M, et al: Client outcomes in two model capitated integrated service agencies. Psychiatric Services 47:175-180, 1996Google Scholar

42. Ziguras SJ, Stuart GW: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatric Services 51:1410-1421, 2000Google Scholar

43. Wolfenden K, Blanchard P, Probst S: Recruitment and retention: perceptions of rural mental health workers. Australian Journal of Rural Health 4:89-95, 1996Google Scholar

44. Meyer PS, Morrissey JP: Assertive Community Treatment in North Carolina: Implementation Status and Training Needs. Chapel Hill, NC, Cecil G Sheps Center for Health Services Research, 2004Google Scholar

45. Moser LL, Deluca NL, Bond GR, et al: Implementing evidence-based psychosocial practices: lessons learned from statewide implementation of two practices. CNS Spectrums 9:926-936, 942, 2004Google Scholar

46. Mueser KT, Torrey WC, Lynde D, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices for people with severe mental illness. Behavior Modification 27:387-411, 2003Google Scholar

47. Bond GR, Salyers MP: Prediction of outcome from the Dartmouth assertive community treatment fidelity scale. CNS Spectrums 9:937-942, 2004Google Scholar

48. Latimer EA: Economic impacts of assertive community treatment: a review of the literature. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 44:443-454, 1999Google Scholar

49. McHugo GJ, Drake RE, Teague GB, et al: Fidelity to assertive community treatment and client outcomes in the New Hampshire Dual Disorders Study. Psychiatric Services 50:818-824, 1999Google Scholar

50. Santos AB, Deci PA, Lachance KR, et al: Providing assertive community treatment for severely mentally ill patients in a rural area. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:34-39, 1993Google Scholar

51. Mueser KT, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al: Models of community care for severe mental illness: a review of research on case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:37-74, 1998Google Scholar

52. Intagliata J: Improving the quality of community care for the chronically mentally disabled: the role of case management. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:655-674, 1982Google Scholar

53. Neale MS, Rosenheck R, Castrodonatti J, et al: Mental health intensive case management (MHICM), in Seventh National Performance Monitoring Report—FY 2003: VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center Report. West Haven, Conn, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2004Google Scholar

54. Scott JE, Dixon LB: Assertive community treatment and case management for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:657-668, 1995Google Scholar

55. McDonel EC, Bond GR, Salyers M, et al: Implementing assertive community treatment programs in rural settings. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 25:153-173, 1997Google Scholar

56. Clark RE, Drake R, Teague GB: The costs and benefits of case management, in Case Management for Mentally Ill Patients: Theory and Practice. Edited by Harris M, Bergman H. Langhorne, Pa, Harwood Academic/Gordon, 1993Google Scholar

57. Draine J: A critical review of randomized field trials of case management for individuals with serious and persistent mental illness. Research on Social Work Practice 7:32-52, 1997Google Scholar

58. Ziguras SJ, Stuart GW, Jackson AC: Assessing the evidence on case management. British Journal of Psychiatry 181:17-21, 2002Google Scholar

59. D'Ercole A, Struening E, Curtis JL, et al: Effects of diagnosis, demographic characteristics, and case management on rehospitalization. Psychiatric Services 48:682-688, 1997Google Scholar

60. Blank MB, Jodl KM: Psychosocial rehabilitation program characteristics in urban and rural areas. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 20:3-10, 1996Google Scholar

61. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003Google Scholar