Brief Report: News Coverage Analyses of Mental Health Services Immediately After September 11, 2001

In the aftermath of disasters, news organizations connect to the public in unique and important ways ( 1 ). Large audiences follow hurricanes or terrorist attacks via the news, and news professionals are positioned where they sometimes play a critical role in the demand for and provision of mental health services after a disaster. For example, through constant portrayals of traumatic events, news can magnify a population's psychological response to disaster ( 2 ). Alternatively, contextual information in disaster reporting can help the public identify their own responses, determine if their responses are normal, and connect with social supports ( 3 ).

Existing studies of mental health news coverage tend to focus on violent behaviors and criminalization of persons with mental illness ( 4 ). Studies of disaster coverage often focus on inadequacies in reporting and myth perpetuation ( 5 , 6 ). Despite much research on the provision of mental health services after disasters ( 7 ), no known studies have examined how journalists portray access to mental health resources in crises.

To begin to address this gap, cross-sectional content analysis was used to describe news reporting of information related to mental health in the two weeks after September 11, 2001. This study specifically examined how U.S. news coverage mentioned aspects of mental health and identified populations at risk of emotional problems or mental disorders, described coping mechanisms for emotional distress, provided mental health support contact information, and used expert mental health sources.

Methods

News stories disseminated from September 11 to 25, 2001, by U.S. daily newspapers and national, broadcast, and cable outlets were obtained from the LexisNexis general news database. Search terms representing the attacks were September 11, variants of the terms terror, attack or attacks, Pentagon, World Trade Center, Somerset County, Flight 11, Flight 175, Flight 93, and Flight 77. Search terms for mental health were mental health, mental illness, depression, anxiety, stress, post traumatic stress, PTSD, counseling, grief, and mourning. The resulting 10,428 stories combining attack and mental health terms came from 119 U.S. newspapers and 19 broadcast and cable outlets.

To improve the efficiency of the estimates, news organizations were divided into strata on the basis of three characteristics predicted to influence variation in reporting: market size, geographic proximity to an attack, and medium. Newspapers were allocated into four strata: daily newspapers that were in the top 50 circulation and were located close to an attack, daily newspapers that were in the top 50 circulation and were not located close to an attack, daily newspapers that were not in the top 50 circulation and were located close to an attack, and daily newspapers that were not in the top 50 circulation and were not located close to an attack. National broadcast and cable transcripts were allocated into a fifth stratum. A 7 percent random sample was selected from each stratum, with an oversample of stratum 3 to ensure adequate representation. After eliminating duplicates, the final sample contained 772 news stories.

Two research assistants each coded half of the stories. To measure interrater agreement, both coded every tenth one. Four elements of each story were captured: at-risk populations, coping mechanisms, contact information for mental health support, and expert mental health sources. The agreement rate across all study variables was 72 percent.

We attempted to determine the proportion of nationwide reports on the attacks that addressed mental health issues. Terms related to the attacks but not to mental health were used to search the same LexisNexis database used in creating our sample. This yielded more than 1,000 stories per day during the two weeks after September 11, 2001. Because the LexisNexis software cannot provide an exact story count if search terms yield more than 1,000 stories per day, this approach was not feasible.

In an alternative approach, we used terms related to the attacks but not to mental health to search 17 print news sources in the LexisNexis database for New York State. From that archive, 10,510 articles mentioned the attacks during the study period. Of these reports, a subsequent search found that 1,516 (14 percent) mentioned mental health terms. By using the assumption (based on our results below) that 57 percent of the articles that mentioned the attacks and mental health services together would be relevant to our search (that is, the combination of search terms was not random), 864 of the 1,516 articles would be relevant to our study, or 8 percent overall (864 of 10,510). Eight percent is likely an overestimate of mental health reporting throughout the United States in the aftermath of September 11, 2001, given that the demand for mental health services was likely greatest in New York City, the location of Ground Zero, and therefore, more news stories from this area would mention these issues.

Results

Of the 772 news stories sampled from reports mentioning the attacks and mental health services together, 438 of these stories (57 percent) were relevant to our study. The remaining analysis focuses on these 438 mental health stories.

Thirty-five of the mental health stories (8 percent) included at least one risk factor for developing emotional problems after the attacks. Six of the stories (1 percent) mentioned risk associated with personal health history. Three stories (1 percent) mentioned an indirect experience, such as watching the attacks on television. The most frequently mentioned risk factor for developing emotional problems, direct experience of the trauma, appeared in 29 stories (7 percent).

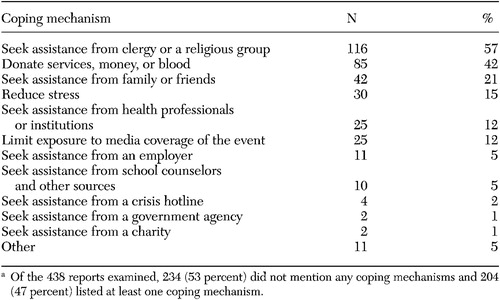

As shown in Table 1 , one or more coping strategies for dealing with emotional problems after the attacks appeared in 204 stories (47 percent). Of those 204 stories, seeking assistance from clergy or a religious group was the most frequently cited coping mechanism; 116 stories (57 percent) included that information. Seeking assistance from a health professional or health institution was mentioned less frequently: 25 stories (12 percent) included that information.

|

a Of the 438 reports examined, 234 (53 percent) did not mention any coping mechanisms and 204 (47 percent) listed at least one coping mechanism.

Contact information for mental health support by telephone or through the Internet was mentioned in 20 stories (6 percent).

Ninety-seven stories (22 percent) cited an expert source. Health professionals were the most frequently cited experts and were mentioned in 42 stories (10 percent), followed by 31 (7 percent) citing religious leaders and 30 (7 percent) citing academic researchers.

Discussion

Our analyses show that a majority of news reports about the attacks did not mention mental health issues. When mental health was mentioned, information that could assist the country in coping with the psychological aftermath of the attacks was lacking. Few articles alerted news audiences to risk factors likely to influence their psychological reaction to the attacks of September 11, 2001, missing an opportunity to prompt audiences to assess their reactions. For people who recognized their risk of developing emotional problems or who sought help for themselves or loved ones, about half of the mental health articles described general coping mechanisms. Very few stories provided specific contact information to link audiences with specific resources.

This news coverage highlighted the range of formal and informal resources that people rely on in crisis situations. For example, news organizations' portrayals of clergy as a source of support mirrors research showing that people turn to religious and spiritual coping mechanisms after exposure to mass disaster ( 8 ). Informal coping mechanisms—such as seeking help from clergy, family, or friends; making donations; or reducing stress—were cited much more frequently than formal coping mechanisms—such as seeking help from health professionals, employers, school counselors, crisis hotlines, government agencies, or charities. Although health professionals were not the most frequently cited coping mechanism, they were cited most frequently as an expert source.

One limitation of this study is the lack of precision in mental health keywords used to conduct a search of the LexisNexis database. Additional terms may have captured a higher percentage of relevant articles. In addition, we based the assessment of gaps in coverage on an assumption that if at least 50 percent of the relevant articles mentioned key information about risk factors for emotional distress or factors for coping with such distress, the information would be adequately disseminated. Better guidelines for reporting on mental health issues and assessing the results are needed and could be modeled on work by the Dart Center on Journalism and Trauma at the University of Washington and the Association of Health Care Journalists. Finally, although these news sources are representative of the news outlets in LexisNexis, it is not clear how adequately all news coverage is represented.

Conclusions

The results suggest that further consideration of mental health reporting after disasters is warranted. For example, health professionals were a top source for information in these reports and were tied for fifth place as a mentioned source for help. This combination may reflect journalists' reliance on medical experts to explain health issues but a reluctance to recommend mental health services. To the extent that information in the news helps to triage potential patients, the result may be a suboptimal demand for psychiatric care. Patients needing psychiatric care may instead be treated inadequately in other settings. Additional research is required to explain whether this trend results from journalists' training or preferences for objectivity or whether it reflects a cultural stigma toward mental illnesses, in which journalists are reluctant to mention a resource that they assume readers would rather avoid.

Further efforts to understand the dissemination of mental health information in a crisis could assist mental health experts and journalists to expand their abilities in helping the public cope with disasters.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kristina Hanson, Shoou-Yih Daniel Lee, Andrew Perrin, Chanequa Walker-Barnes, and Wendy Wolford for commenting on the manuscript. The authors also thank Ashley Manos, Carrie Johnson, Katrina Rankins, and especially Suja Rajan for their assistance.

1. Perez-Lugo M: Media uses in disaster situations: a new focus on the impact phase. Sociological Inquiry 74:210-225, 2004Google Scholar

2. Ahern J, Galea S, Resnick H, et al: Television images and psychological symptoms after the September 11 attacks. Psychiatry 65:289-300, 2002Google Scholar

3. Felton C: Project Liberty: a public health response to New Yorkers' mental health needs arising from the World Trade Center terrorist attacks. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 79:429-433, 2002Google Scholar

4. Sieff EM: Media frames of mental illness: the potential impact of negative frames. Journal of Mental Health 12:259-269, 2003Google Scholar

5. Fischer HW: Response to Disaster: Fact vs Fiction and Its Perpetuation, 2nd ed. University Press of America, 1998Google Scholar

6. Quarantelli EL: Local mass media operations in disasters in the USA. Disaster Prevention and Management 5:5-10, 1996Google Scholar

7. Norris F, Friedman JF, Watson PJ, et al: 60,000 disaster victims speak: part II. summary and implications of the disaster mental health research. Psychiatry 65:240-260, 2002Google Scholar

8. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox L, et al: A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. New England Journal of Medicine 345:1507-1512, 2001Google Scholar