Treatment Seeking for Depression in Canada and the United States

Community surveys over the past two decades have consistently found that most U.S. adults with mental disorders do not receive any mental health care for their symptoms ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ). This problem persists in part because U.S. policy makers lack critical information about modifiable determinants of mental health care utilization—data that could inform initiatives to redesign the U.S. health care system.

Previous epidemiological research on mental health care seeking has focused almost entirely on patient and provider factors, with little attention to the potentially large impact of health care policy, the service system, and other contextual factors. Only a few cross-national comparisons have sought to collect information on mental health treatment seeking from countries with different service delivery systems ( 7 , 8 ). For example, comparisons have been drawn betweenmental health care utilization in the United States and Ontario, Canada ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ). Despite geographical and sociocultural proximity, the U.S. and Canadian mental health care systems differ in several respects ( 14 ). Most important, Canada has a single-payer system rather than the patchwork of private and public payment sources that characterizes the U.S. health care system. Furthermore, the Canadian system provides full parity for mental health services, whereas in the United States, only some states have passed mental health care parity legislation and only a few private insurers have voluntarily adopted such policies. Finally, mental health services rendered by nonphysicians outside of hospitals are generally not covered in Canada, whereas most U.S. public and private insurance plans cover these services ( 14 ).

Studies that have compared the United States and Ontario ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ) revealed no significant differences in time lag from onset of common mood and anxiety disorders to first treatment contact ( 12 ). Nevertheless, more U.S. adults than Ontarian adults reported seeking professional help in a 12-month period ( 9 , 11 ). This difference, however, was limited to participants without mental health conditions. Surprisingly, U.S. participants with affective and other serious mental disorders were less likely than their Ontarian counterparts to seek care ( 9 , 11 ). For example, 30.4 percent of U.S. adults with major depression sought mental health care in a one-year period compared with 54.7 percent of comparable Ontarians ( 10 ). These comparisons, however, were limited to one Canadian province and may not be representative of all Canada. Furthermore, the data were collected in the early 1990s and may not represent contemporary service use patterns ( 15 ).

The study presented here assessed recent between-country differences in mental health treatment seeking for major depression. Data were based on secondary analyses of a cross-sectional general population survey conducted jointly in both countries—the 2002-2003 Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health (JCUSH). We focused on three questions: How do the two countries differ with respect to the prevalence of mental health treatment seeking and treatment seeking from specific providers by individuals with major depression? How do the predictors for treatment seeking differ in the two countries? Are cross-country differences in treatment seeking consistent across sociodemographic groups traditionally reported to have better access to health care?

Methods

Sample

The JCUSH was a telephone survey conducted between 2002 and 2003. It was sponsored by the U.S. National Center for Health Statistics and by Statistics Canada and is described in detail elsewhere ( 16 , 17 ). The survey sampled representative community-dwelling adults stratified by province in Canada and by four geographic regions in the United States. Institutionalized populations and persons living in Canadian or U.S. territories were excluded. To ensure a sufficient sample of older adults, individuals older than 65 years were oversampled.

Households were selected through random-digit dialing. In randomly selected households, a knowledgeable adult household member was asked to supply basic demographic information on all household residents. From these households, an adult household member was then randomly selected for an in-depth interview. In cases in which the selected individual was not capable of completing the interview, a knowledgeable member of the household served as a proxy by supplying information about the selected participant.

Overall, 3,099 individuals in Canada and 5,054 in the United States were interviewed. Response rates were 66 percent in Canada and 50 percent in the United States. Final study weights were computed to adjust for oversampling and to make the composition of samples representative of the household adult population of the two countries.

Assessments

Presence of a probable major depressive episode in the past 12 months and severity and duration of depressive episodes were ascertained by using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short-Form (CIDI-SF) ( 18 ). The CIDI-SF is a structured diagnostic interview designed for use by trained nonclinician interviewers that screens for DSM-IV disorders ( 19 ). CIDI-SF asks about eight symptoms of major depressive disorder in the past 12 months. Individuals who endorse five or more symptoms meet the DSM-IV symptom criteria for a major depressive episode. Previous analyses have shown that individuals who endorse five or more CIDI-SF symptoms for a minimum duration of two weeks have an 89 percent probability of meeting full CIDI criteria for a major depressive episode ( 20 ). This cut-off point was used in our study to define probable major depressive episode in the past 12 months (present, 1, or absent, 0). The number of symptoms endorsed was used as an indicator of severity of the depressive episode (range, five to eight).

Severe impairment in functioning as a result of mental health problems was assessed by asking the participants a series of questions about "difficulties" they may have in "doing certain activities because of a health problem." Health problem was defined as "any physical, mental, or emotional problem or illness." Difficulties listed included difficulties in physical activities, such as walking, using fingers to grasp or handle small objects, and carrying objects; difficulties with activities outside the house, such as shopping or participating in social activities; and difficulty in doing things to relax at home or for leisure. Participants who reported difficulties in at least three specific activities were asked which health problem from a list of 18, including "depression/anxiety/emotional problem," caused the difficulties. Severe impairment in functioning caused by mental health problems was defined as difficulties in at least three areas attributed to "depression/anxiety/emotional problem" (present, 1, or absent, 0).

Sociodemographic characteristics included gender (female, 1, or male, 0), age (18 to 44 years, 45 to 64 years, and 65 years or older), race or ethnicity (minority, 1, or Caucasian, 0), marital status (married or living as married, divorced or separated, widowed, or never married), education (less than high school, high school or equivalent, vocational school or community college, or associate degree or higher), and household income adjusted for the number of persons residing in the household ( 17 ). Participants were assigned to income quintiles by ranking according to the adjusted household income within each country; possible scores ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher income.

Health insurance was assessed only among U.S. participants because all Canadians are covered by the Canadian universal insurance plan. U.S. participants were categorized into those with health insurance coverage throughout the past year, those with insurance coverage for only part of the past year, and those without insurance coverage throughout the past year.

Regular medical doctor was ascertained by asking participants if they had a regular medical doctor (yes, 1, or no, 0).

Chronic medical conditions were ascertained by asking participants if they had asthma, arthritis, hypertension, emphysema, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, coronary heart disease, or angina, or if they had had a heart attack. Participants were asked if they had ever been told "by a doctor or other health professional" that they had each condition and whether they still had that condition. Participants who reported currently having any of these conditions were rated as having a chronic medical condition (present, 1, or absent, 0).

General health was rated on a 5-point Likert scale. Possible scores range from 0, poor, to 4, excellent.

Mental health treatment seeking was assessed with one question: "In the past 12 months have you seen or talked on the telephone to a health professional about your emotional or mental health?" Participants who reported having seen or talked to a health professional were asked about the number of such contacts and whether the contact was with a family doctor or general practitioner, psychiatrist, psychologist, nurse, social worker or counselor, or other professional. Contact with health professionals for mental health reasons was rated dichotomously as present, 1, or absent, 0. It should be noted that this definition of mental health treatment seeking is admittedly broad and does not necessarily correspond with receiving adequate mental health treatment or even any treatment. Participants were also asked if they had taken prescription medications for any condition in the past month (yes, 1, or no, 0). The type of medication or indication for use was not ascertained.

Perceived unmet need for mental health care was assessed by first asking the participants if during the past 12 months they ever felt that they needed health care but did not receive it. Participants who responded positively were then asked about the type of care that they felt they needed but did not receive. Participants who indicated that they had not received needed "treatment of an emotional or mental health problem" were rated as having perceived unmet need for mental health care (unmet need, 1, or no unmet need, 0).

Analyses

Analyses were conducted in four stages. First, as a preliminary step, the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants with a probable major depressive episode in the two countries were compared by using contingency table analysis for categorical variables and the adjusted Wald test for continuous variables.

Second, participants in each country who had a probable major depressive episode were compared with respect to mental health treatment seeking from any provider, the type of provider, the use of prescription medications, perceived unmet need for mental health care, and number of mental health visits. Again, contingency table analysis and the adjusted Wald test were used for these analyses. The analyses were limited to participants with a probable major depressive episode. The analysis for comparing mental health treatment seeking from any provider across the countries was repeated in a multivariate logistic regression model, which adjusted for gender, age, race or ethnicity, marital status, education, household income, having a regular medical doctor, having a chronic medical condition, general health rating, severe impairment in functioning, number of CIDI-SF symptoms, and duration of depressive episode.

Third, the association of sociodemographic characteristics with mental health treatment seeking from any provider among participants with a probable major depressive episode was assessed separately in the two countries with bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models in which the dichotomous variable of treatment seeking was the dependent variable of interest and the sociodemographic characteristics of individuals were the independent variables of interest. Multivariate analyses produced odds ratios that were adjusted for all variables in the model described above. In addition, analyses for the U.S. sample adjusted for insurance status.

Fourth, to assess whether the findings were consistent across sociodemographic groups traditionally reported to have better access to health care, the analyses described in stage 3 for the association of the variables of number of depressive symptoms and mental health treatment seeking from any provider were repeated among participants in the upper three income quintiles, Caucasians, and U.S. participants with insurance coverage throughout the past year. Also, because some individuals continue education after the age of 18 years, the analyses of the relationship between education and mental health treatment seeking from any provider were repeated among participants with a probable major depressive episode who were older than 21 years.

Missing data were dealt with by using the method of dummy variable coding ( 21 ) in which the missing values were replaced by the reference category on categorical variables (coded as 0) and the lowest values in the range on ordinal and continuous variables (for example, 1 for household income quintiles) and by entering a dummy variable for missing data (missing, 1, or not missing, 0) along with each variable in the logistic regression models of the third and fourth stages of the analysis described above. It should be noted, however, that data were missing for only a small number of cases, and adjusting the analyses for missing values had a minimal impact on the results of the analyses. For 12 of the 13 independent variables in regressions reported in Table 3 , fewer than 6 percent of the cases had missing values. The variable with the largest number of missing values was household income, with 17 percent of the cases having missing values on this variable.

|

Because the JCUSH used a complex stratified sampling design, the analyses were conducted by the "svy" routines of STATA 8.0 software ( 22 ), which take into account the design elements of the survey, including survey weights, primary sampling units, and strata. For analysis of contingency tables based on complex survey data, STATA reports an F statistic (with noninteger degrees of freedom when the categories exceed two). This F statistic is computed from the usual Pearson chi square test by using a correction ( 23 ) to account for the complex survey design. The p value for this F statistic can be interpreted in the same way as a p value for a Pearson chi square. The rationale and computation details for this F statistic have been described by Rao and Thomas ( 23 ). Statistical testing for comparison of means on continuous variables is by adjusted Wald test, which also produces an F statistic ( 24 ). Statistical testing of logistic regression coefficients is conducted by using t tests with degrees of freedom equal to the number of primary sampling units minus the number of strata ( 25 , 26 ). Technical description of these tests is beyond the scope of this paper and can be found elsewhere ( 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ). All reported percentages are weighted. A p value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of Canadian and U.S. participants

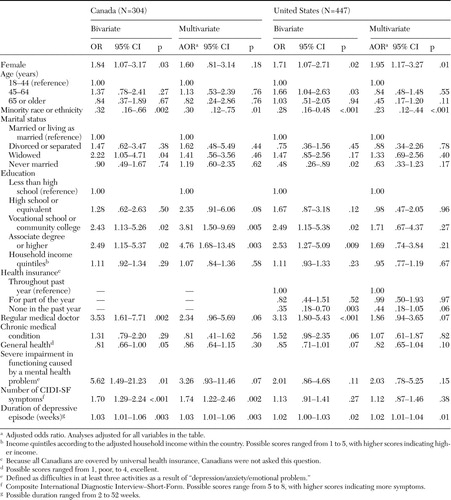

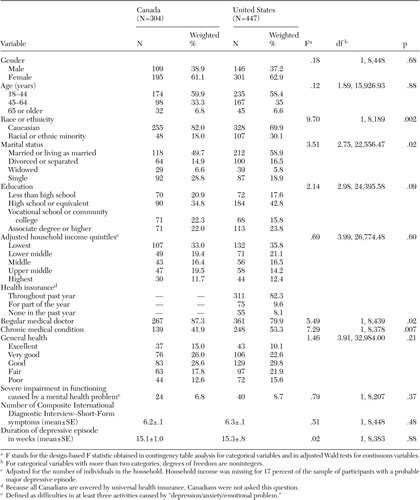

A total of 304 Canadian participants (8.2 percent) and 447 U.S. participants (8.7 percent) were classified as having had a probable major depressive episode. As shown in Table 1 , the two groups differed significantly in several sociodemographic and background characteristics. Specifically, compared with the Canadian group, a larger proportion of the U.S. participants with a probable major depressive episode was from a racial or ethnic minority group, was currently married or living as married, and had a chronic medical illness, although a smaller proportion had a regular doctor. Except for the difference in marital status, other differences between the countries were observed among participants without major depressive episodes as well as those with major depressive episodes.

|

Comparison of the rates of mental health treatment seeking

In the bivariate analyses, no difference was found in the rates of mental health treatment seeking from any provider between Canadian and U.S. adults with a probable major depressive episode ( Table 2 ). Canadians with a probable major depressive episode were more likely than their U.S. counterparts to seek treatment from a family doctor or general practitioner. Canadian participants with a probable major depressive episode who saw a family doctor or general practitioner were more likely than their U.S. counterparts to also see a psychiatrist or psychologist ( Table 2 ). The number of visits was similar across countries. The lack of difference between the two countries in prevalence of mental health treatment seeking from any provider observed in bivariate analysis persisted in a multivariate logistic regression analysis that controlled for all sociodemographic variables found in Table 1 (data not shown).

|

Predictors of mental health treatment seeking

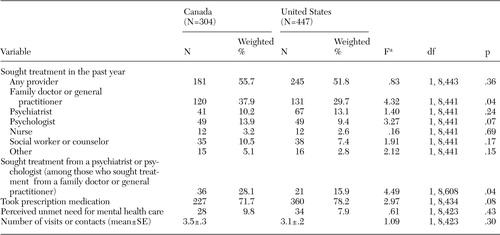

Among Canadian participants with a probable major depressive episode, female gender, widowhood, more education, having a regular medical doctor, severe impairment in functioning as a result of mental health problems, number of depressive symptoms, and the duration of the depressive episode were each associated in bivariate analyses with a higher likelihood of mental health treatment seeking from any provider. However, being from a racial or ethnic minority group was associated with a lower likelihood of treatment seeking ( Table 3 ). In multivariate analysis, the association persisted with minority status, education, number of symptoms, and duration of depressive episode ( Table 3 ).

Among U.S. participants with a probable major depressive episode, female gender, being in the 45 to 64 age range, higher education level, having a regular medical doctor and duration of depressive episode were each associated in bivariate analyses with a greater likelihood of mental health treatment seeking from any provider; however, being from a racial or ethnic minority group, being never married, and having no insurance in the past year were each associated with a lower likelihood of treatment seeking ( Table 3 ). In the multivariate analysis in the U.S. sample, the associations persisted with gender, minority status, and duration of depressive episode ( Table 3 ).

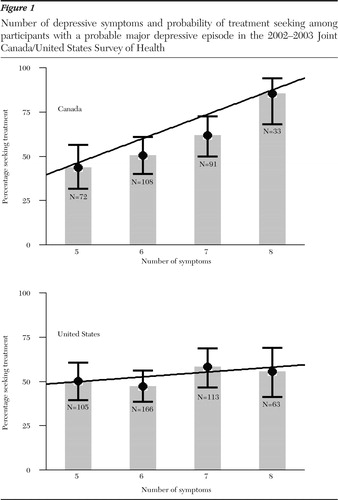

The most consistent associations across bivariate and multivariate models were those with minority status and with duration of depressive episode, which were similar across countries, and with the number of depressive symptoms, which was significant only in Canada. Figure 1 depicts the associations of number of symptoms with mental health treatment seeking from any provider in the United States and Canada.

Analyses for specific sociodemographic groups

To assess whether the observed association of number of depressive symptoms and treatment seeking was also observed among sociodemographic groups traditionally reported to have better access to health care, these analyses were repeated among participants in the upper three income quintiles, Caucasians, and U.S. participants with insurance coverage throughout the past year.

In the Canadian sample, the relationship held in bivariate and multivariate analyses when the sample was limited to those in the three highest income quintiles (multivariate adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.59, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.02 to 2.51; t=2.03, df=2,117, p=.04) and to Caucasians (AOR=1.66, CI=1.12 to 2.44; t=2.54, df=2,848, p=.01). Whereas, in the U.S. sample, a significant relationship did not emerge in the bivariate or multivariate analyses that were limited to participants in the three highest income quintiles, to Caucasians, or to those with insurance throughout the past year.

The analyses for the relationship between education and treatment seeking were also repeated in the subsamples of adults with a probable major depressive episode who were older than 21 years. As in the main analyses ( Table 3 ), education remained a significant predictor in bivariate analyses for both countries. In multivariate analyses, education significantly predicted treatment seeking in the Canadian subsample (for high school, AOR=2.64, CI=1.03 to 6.71; t=2.03, df=3,219, p=.04; for vocational school or community college, AOR=3.83, CI=1.57 to 9.33; t=2.96, df=3,219, p=.003; for associate degree or higher, AOR=4.88, CI=1.76 to 13.56; t=3.04, df=3,219, p=.002) but not in the U.S. subsample.

Discussion

The results of this study revealed differences and similarities in patterns of mental health treatment seeking among individuals with probable major depression in Canada and in the United States. First, the prevalence of treatment seeking from any provider did not significantly differ between the two countries. This finding contrasts with reports from the early 1990s that showed that among adults with major depression, fewer Americans than Ontarians sought mental health care in the past 12 months (30.4 percent in the United States compared with 54.7 percent in Ontario) ( 10 ).

Changes over time in prevalence of treatment seeking in Canada and the United States may explain the discrepancy between the earlier studies and the study reported here. In the United States, the rate of treatment seeking for depression markedly increased between the late 1980s and early 1990s ( 15 ) and continued to increase through the 1990s ( 2 , 23 ). In contrast, outpatient treatment among individuals with major depression in Canada did not change significantly between 1994 and 2001 ( 27 ). The results of our study suggest that with the recent increase in the U.S. rates of treatment seeking for depression, the wide gap between the two countries has significantly narrowed. In contrast to rates of treatment contacts, the rates of antidepressant treatment among those who did seek treatment were remarkably similar in the early 1990s ( 10 ) and have since increased in both countries ( 15 , 27 ).

The second major finding is that Canadians continued in larger numbers to seek mental health treatment from primary care providers rather than psychiatrists or psychologists ( 10 ). Furthermore, Canadians with depression who saw a primary care provider for mental health care were almost two times as likely as their U.S. counterparts to see a psychiatrist or psychologist in addition to the primary care provider. This difference may be partly due to barriers in the U.S. managed health care system that constrain referral to specialty mental health providers ( 28 ). It is also possible that Canadian primary care physicians are more willing to refer patients to mental health professionals than their U.S. counterparts. Alternatively, it is possible that Canadian patients feel less stigmatized by a mental health referral than U.S. patients. The cause of these differences in referral practices as well as their impact on the treatment and outcome of depression and other common mental health conditions needs to be explored in future research.

Third, we found that few differences existed between the countries in determinants of treatment seeking for depression. Nevertheless, severity of depression was associated with a greater likelihood of seeking treatment in Canada but not in the United States. Thus there appears to be a closer correspondence between the severity of depression and treatment seeking in Canada than in the United States, suggesting that allocation of mental health treatment resources may be more efficient in Canada.

This finding contrasts with some of the earlier research on correlates of treatment seeking for depression ( 29 , 30 ) and may be related to the recent general increase in depression treatment in the United States. It is notable, however, that previous research comparing Ontario and the United States also revealed a stronger association between disorder severity and treatment seeking in Ontario than in the United States for a broad range of mental disorders ( 9 ). This line of research has also suggested that differences in rates of perceived need for services may explain differences in treatment seeking across countries ( 11 ). Individuals with mild symptoms of a mental disorder in the United States were more likely than their Ontarian counterparts to perceive a need for mental health care ( 11 ). One possible explanation proposed was that the Ontario health care system is more effective than the U.S. system in educating patients about the appropriate level of need that would justify treatment seeking ( 9 ). Alternatively, Ontarians may have a more stoic attitude than U.S. adults in coping with ill health and suffering ( 9 ).

In our study, subgroup analyses suggested that cross-country differences in the relationship between depression severity and treatment seeking were not limited to socioeconomically disadvantaged subgroups. Although other individual and social factors may explain this difference, it is possible that the Canadian health care or public information systems are more effective in educating patients about mental health issues, and as a result, Canadians may be more knowledgeable about the "warning signs" of serious depression than Americans. In this regard, it is notable that higher levels of formal education were more strongly and consistently related to treatment seeking in Canada, compared with the United States. It may be that the Canadian education system does a better job of educating and informing the public about mental health and the need for mental health treatment than the education system in the United States.

In both countries, race and ethnicity were significantly associated with treatment seeking. Participants who were from racial or ethnic minority groups were much less likely than Caucasians to seek treatment. The enduring racial disparity in treatment seeking in the two countries remains a cause for concern. Persistent racial disparities in use of services in Canada suggest that universal health coverage does not necessarily eliminate disparities in access to health care ( 31 , 32 , 33 ). Racial or ethnic differences in attitudes about mental illness and mental health treatment may play at least as significant a role as financial barriers ( 34 ).

There are a number of limitations to the JCUSH data, and the results of this study should be viewed in the context of these limitations. First, a substantial proportion of eligible participants did not participate, and no information is available concerning their characteristics. Although survey weights seek to adjust for nonresponse, the threat of selection bias remains an important limitation. Second, although 98.2 percent of Canadian and 95.6 percent of U.S. households have a telephone ( 17 ), random-digit dialing excludes households without a telephone and oversamples households with more than one telephone number. Third, JCUSH excludes institutionalized and homeless individuals, so the results do not apply to these important groups that likely each have a distinct pattern of mental health treatment seeking. Fourth, the analyses are vulnerable to social desirability and recall biases associated with self- or proxy-report data collection. Furthermore, diagnoses from the lay-administered CIDI-SF do not necessarily correspond with clinician diagnoses or those based on clinician-administered semistructured interviews, such as the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia ( 35 ) or other clinician-administered interviews ( 36 ). Fifth, because JCUSH data are cross-sectional, causal relationships cannot be inferred. Sixth, treatment seeking was operationalized here as any contact with health professionals for mental health problems. As noted earlier, this definition of treatment seeking is broad. Some individuals who seek mental health treatment may not receive adequate treatment or even any treatment. Finally, data were not available for a number of individual characteristics that may influence treatment seeking, including age of onset of depression ( 12 , 37 ), comorbid psychiatric conditions ( 1 , 37 ), level of impairment ( 30 , 37 ), and attitudes about mental illness and mental health treatment ( 38 ). The association of these factors with treatment seeking in the two countries needs to be assessed in future studies.

Conclusions

Our study found significant similarities and differences in mental health treatment seeking for depression between Canada and the United States. Comparison of the data reported here with past research suggests that in recent years the between-country gap in the overall prevalence of mental health treatment seeking for depression has significantly narrowed. However, differences in use of various providers do persist. Furthermore, there appears to be a closer correspondence between severity of depression and treatment seeking in Canada than in the United States. Key challenges ahead include evaluating whether, in relation to the United States, the Canadian mental health system confers superior health outcomes for depressed adults and, if so, which aspects of the Canadian system contribute to the more efficient allocation of mental health services.

1. Bland RC, Newman SC, Orn H: Help-seeking for psychiatric disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:935-942, 1997Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, et al: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:115-123, 1999Google Scholar

3. Narrow WE, Regier DA, Norquist G, et al: Mental health service use by Americans with severe mental illnesses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:147-155, 2000Google Scholar

4. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993Google Scholar

5. Shapiro S, Skinner EA, Kessler LG, et al: Utilization of health and mental health services: three Epidemiologic Catchment Area sites. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:971-978, 1984Google Scholar

6. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, et al: Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:629-640, 2005Google Scholar

7. Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al: Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291:2581-2590, 2004Google Scholar

8. Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al: Use of mental health services in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica: Supplementum (420):47-54, 2004Google Scholar

9. Kessler RC, Frank RG, Edlund M, et al: Differences in the use of psychiatric outpatient services between the United States and Ontario. New England Journal of Medicine 336:551-557, 1997Google Scholar

10. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Lin E, et al: Medication management of depression in the United States and Ontario. Journal of General Internal Medicine 13:77-85, 1998Google Scholar

11. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Frank RG, et al: The use of outpatient mental health services in the United States and Ontario: the impact of mental morbidity and perceived need for care. American Journal of Public Health 87:1136-1143, 1997Google Scholar

12. Olfson M, Kessler RC, Berglund PA, et al: Psychiatric disorder onset and first treatment contact in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1415-1422, 1998Google Scholar

13. Edlund MJ, Wang PS, Berglund PA, et al: Dropping out of mental health treatment: patterns and predictors among epidemiological survey respondents in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:845-851, 2002Google Scholar

14. MacKenzie KR: Canada: a kinder, gentler health care system? Psychiatric Services 50:489-491, 1999Google Scholar

15. Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, et al: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203-209, 2002Google Scholar

16. Joint Canda/United States Survey of Health Public Use Microdata File User Guide. Statistics Canada and United States National Center for Health Statistics, 2004, Available at www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/82M0022XIE/2003001/pdf/userguide.pdf. Accessed Nov 10, 2005Google Scholar

17. Sanmartin C, Ng E, Blackwell D, et al: Joint Canada/United States Survey of Health, 2002-03. Statistics Canada, National Center for Health Statistics, US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Minister of Industry, Canada, 2004. Available at www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/82M0022XIE/2003001/pdf/82M0022XIE2003001.pdf. Accessed Nov 10, 2005Google Scholar

18. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al: The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:171-185, 1998Google Scholar

19. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

20. Walters EE, Kessler RC, Nelson CB, et al: Scoring the World Health Organization's Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF), 2002. Available at www3.who.int/cidi/cidisfscoringmemo12-03-02.pdf. Accessed November 10, 2005Google Scholar

21. Cohen J: Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Mahwah, NJ, Erlbaum, 2003Google Scholar

22. Stata Statistical Software, Release 8.0. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2003Google Scholar

23. Rao JNK, Thomas DR: Chi-squared tests for contingency table, in Analysis of Complex Surveys. Edited by Skinner CJ, Holt D, Smith TMF. New York, Wiley, 1989Google Scholar

24. Korn EL, Graubard BI: Simultaneous testing of regression coefficients with complex survey data: use of Bonferroni t statistics. American Statistician 44:270-276, 1990Google Scholar

25. Stata Programming Reference Manual. College Station, Tex, Stata Press, 2003Google Scholar

26. Binder DA: On the variances of asymptomatically normal estimators from complex surveys. International Statistical Review 51:279-292, 1983Google Scholar

27. Patten SB, Beck C: Major depression and mental health care utilization in Canada: 1994 to 2000. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 49:303-309, 2004Google Scholar

28. Trude S, Stoddard JJ: Referral gridlock: primary care physicians and mental health services. Journal of General Internal Medicine 18:442-449, 2003Google Scholar

29. Olfson M, Klerman GL: Depressive symptoms and mental health service utilization in a community sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 27:161-167, 1992Google Scholar

30. Bristow K, Patten S: Treatment-seeking rates and associated mediating factors among individuals with depression. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 47:660-665, 2002Google Scholar

31. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, et al: Ethnicity and the use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. American Journal of Public Health 84:222-226, 1994Google Scholar

32. Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, et al: Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Medical Care 40:52-59, 2002Google Scholar

33. Steele LS, Glazier RH, Lin E: Inequity in mental health care under Canadian universal health coverage. Psychiatric Services 57:317-324, 2006Google Scholar

34. Diala C, Muntaner C, Walrath C, et al: Racial differences in attitudes toward professional mental health care and in the use of services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:455-464, 2000Google Scholar

35. Endicott J, Spitzer RL: A diagnostic interview: the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:837-844, 1978Google Scholar

36. Booth BM, Kirchner JE, Hamilton G, et al: Diagnosing depression in the medically ill: validity of a lay-administered structured diagnostic interview. Journal of Psychiatric Research 32:353-360, 1998Google Scholar

37. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al: The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 289:3095-3105, 2003Google Scholar

38. Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D: Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:77-84, 2002Google Scholar