Involvement in the Child Welfare System Among Mothers With Serious Mental Illness

Research suggests that rates of childbearing among women with psychiatric disabilities are similar to those of other women ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). The increase in childbearing among women with psychiatric disabilities over the past three decades ( 2 , 3 ) may be associated with deinstitutionalization, which has led to increased community integration and normalized social activity and expectations ( 4 ). In fact, the ability to have children may be one area in which women with psychiatric disabilities are at an advantage over women with other disabilities ( 5 ).

Mothers with serious mental illness experience many challenges to successful parenting, which are exacerbated by the lack of services specific to their needs ( 6 , 7 ). They are less likely than other women to receive prenatal care ( 2 ) and more likely to use alcohol and other drugs during pregnancy ( 8 ). Perhaps as a result, a greater proportion of women with serious mental illness experience obstetric complications ( 4 ). Mothers with serious mental illness also experience difficulties after the birth of their children. Many have difficulty with the tasks of day-to-day parenting and meeting their children's basic needs ( 4 , 6 , 9 ). Regardless of their specific diagnosis or demographic characteristics, these women experience relatively high levels of parenting stress, problems with discipline, and poor satisfaction with the parent-child relationship ( 10 ). Despite these problems, they often feel hesitant to seek assistance, in part because of fear of losing their children ( 11 , 12 ).

There is some evidence that these fears are justified. The few studies in this area suggest that mothers with serious mental illness are more likely than other mothers to lose custody of their children, although this limited research suggests that they are no more likely to abuse their children ( 2 ). For example, Hollingsworth ( 13 ) found that, among a sample of 322 women with serious mental illness, 26 percent had lost custody of their children at some point. However, interpretation of this finding is limited by the lack of a control group. Sands and colleagues ( 14 ) conducted a qualitative study of 20 mothers with severe mental illnesses and found that they often expressed confusion about the custody status of their children, which brings into question the reliability of self-report of custody arrangements. In a study of 46 women with schizophrenia and 50 women in a control group, Miller and Finnerty ( 2 ) found that 48 percent of women with schizophrenia had children in foster care, compared with 2 percent of women without serious mental illness. These findings were limited by the small sample, which prohibited adjustment for variables of interest, and reliance on self-report of custody arrangements. In a study of 285 families engaged in legal proceedings with the Australian child welfare system about the custody of their children, Llewellyn and colleagues ( 15 ) found that 22 percent of these parents had psychiatric disabilities, although their children were not more likely than other children to be placed in out-of-home care unless the parents were suspected substance abusers. However, the sample for this study was confined to families who had already come to the attention of the child welfare system.

The extent to which mothers with serious mental illness have contact with the child welfare system and lose custody of their children has important implications for service and system planning. The Philadelphia child welfare system, which provided data for the study reported here, has increasingly recognized the mental health needs of children in the foster care system. For example, a joint unit of the Philadelphia Departments of Human Services and Behavioral Health Services has recently been created to ensure that children with pressing mental health problems in the child welfare system are appropriately identified, triaged, and served. The needs of parents with drug and alcohol problems have also been recognized, with improved access to substance abuse treatment for parents who come to the attention of the child welfare system. However, no similar mechanism exists for parents of children with other psychiatric disorders.

The study reported here attempted to extend existing research by using administrative data sets to provide population-based estimates of the association between the presence of maternal mental illness and custodial arrangements. The study also examined the relationship of types of psychiatric care with custody outcomes among mothers who had a psychiatric disorder. On the basis of previous research, we hypothesized that children of these women would be more likely to have had contact with the child welfare system and to be taken from the custody of their mothers.

Methods

Data source

Three administrative data sets from Philadelphia were used to obtain data from 1995 to 2000. Medicaid eligibility files provided information about program eligibility and demographic characteristics for the sample. Medicaid claims files provided information about psychiatric diagnoses and use of mental health services. Child welfare data from the Department of Human Services (DHS) provided information about out-of-home placement and nonplacement preventive services.

DHS houses the child welfare agency for the City of Philadelphia, which is responsible for protecting children from abuse and neglect and ensuring their safety and permanency in nurturing home environments. DHS services include foster care, in-home preventive services, adoption, and investigation of reports of abuse and neglect. Depending on the potential threat to a child's immediate safety implied by an allegation, investigations by DHS caseworkers begin immediately, if warranted, or otherwise within 24 hours. Investigations must be completed within 60 days. Allegations of abuse and neglect are considered substantiated on the basis of medical evidence or admission by the abuser or if the court rules that the child was abused. For substantiated cases, out-of-home care or in-home preventive services are provided depending on the needs of children and families, with a particular focus on child safety.

Analyses from the DHS data set used for the study suggest that nearly 20,000 children and their families in Philadelphia receive DHS services annually, with approximately 4,000 children receiving out-of-home care —which includes foster homes, group homes, and residential institutions—for the first time each year and 8,000 in out-of-home care at any given time. Many children in out-of-home care are initially placed in temporary foster care. Although some children return to their family, others stay in foster care until they find a permanent placement, age out of the system, or abscond from care (run away). In-home preventive services —life skills, parenting education, and service coordination—are intended to prevent children's entry or reentry into out-of-home care and to strengthen family functioning.

Sample

The study sample comprised 4,827 female residents of Philadelphia who were between the ages of 15 and 45 years as of 1996, who were first eligible for Medicaid through Aid to Families With Dependent Children (AFDC) between 1995 and 1996, and who had at least one family member younger than 18 years at the beginning of the study period. These women and their children were identified by using the Pennsylvania Medicaid eligibility files. Children were linked to their mothers by using a nine-digit unique identifier in which the first seven digits identify the family and the last two identify individuals within the family. The Medicaid eligibility files were then linked to the Medicaid service utilization files and the child welfare records by using unique Medicaid identifiers and Social Security numbers. The resulting record contained the Medicaid mental health care utilization records for each mother and the child welfare records for her children over the remaining five years of data.

Measures

Information on demographic characteristics such as age and race or ethnicity was obtained from the Medicaid eligibility files. Age at the beginning of the study was coded in years. Race or ethnicity was coded as African American, Latino, white, and other.

Serious mental illness and other psychiatric diagnoses were measured by using diagnoses from the Medicaid claims. Claims associated with ICD-9 codes 295 (schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders) and 296 (major affective disorders) were categorized as serious mental illnesses. Other ICD-9 codes between 290 and 319 were categorized as "other psychiatric diagnoses." On the basis of findings from previous research ( 16 ), a mother was classified as having a serious mental illness if she had at least one inpatient claim or two outpatient claims during the study period for diagnoses in the category of serious mental illness.

Type of treatment was classified as inpatient care, outpatient care, or no treatment on the basis of the Medicaid claims.

Involvement in the child welfare system was defined as placement in out-of-home care or receipt of in-home preventive services without out-of-home placement from the Philadelphia DHS.

Analysis

The first stage of the analysis was descriptive and examined the distribution of key variables of interest. Next, the prevalence of involvement in the child welfare system was examined. Chi square tests and analysis of variance were used to compare involvement in the child welfare system across psychiatric diagnosis, type of treatment, and demographic characteristics. Multinomial and binary logistic regression analyses assessing the association of study variables with involvement in the child welfare system and out-of-home placements were conducted and compared. Because only minor differences in coefficients were found between the two models, only the binary logistic models are presented for ease of interpretation.

The institutional review board of the University of Pennsylvania approved this study before any analyses were conducted.

Results

Approximately half of the 4,827 mothers were African American, (2,457 mothers, or 50.9 percent), 1,146 (23.7 percent) were Latino, 1,036 (21.5 percent) were white, and 188 (3.9 percent) were from other racial or ethnic groups. The mean± SD age of mothers was 28.8±7.2 at the beginning of the study period. Of the mothers in the sample, 349 (7.2 percent) had a serious mental illness and 213 (4.4 percent) had other psychiatric diagnoses. A small percentage of mothers (156 mothers, or 3.2 percent) had experienced psychiatric inpatient episodes over the five years of the study in addition to outpatient care; 8.2 percent (395 mothers) received outpatient care only.

Overall, 106 mothers (2.2 percent of the sample) had had a child placed in out-of-home care during the study period; an additional 148 (3.1 percent) received in-home preventive services only. As shown in Table 1 , 14.6 percent of mothers with serious mental illness received child welfare services, compared with 10.8 percent of those with other psychiatric diagnoses and 4.2 percent of those without a psychiatric diagnosis. Psychiatric inpatient care was also related to greater involvement in the child welfare system; 16.2 percent of mothers with a history of inpatient care received child welfare services, compared with 11.7 percent of those who received outpatient care only and 4.2 percent who received no psychiatric care.

|

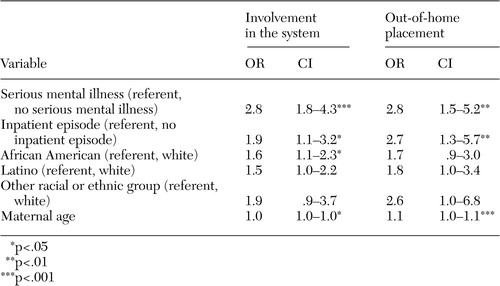

These differences were similar in the multivariate logistic regression ( Table 2 ). After the analysis adjusted for type of treatment, race or ethnicity, and age, mothers with a diagnosis of serious mental illness were almost three times as likely to have had any involvement in the child welfare system or to have children who had an out-of-home placement. Mothers who had had a psychiatric inpatient episode were approximately twice as likely as mothers who had not had such an episode to have had involvement in the child welfare system and nearly three times as likely to have children placed in out-of-home care. For African-American mothers, the likelihood of any involvement in the child welfare system—but not of having children in out-of-home placement—was significantly higher than for white mothers. Increased age was associated with greater risk of involvement in the child welfare system, although the magnitude was small.

|

Discussion and conclusions

This study of a large sample of mothers found that, when the analyses adjusted for race or ethnicity, age, and type of psychiatric care received, mothers with serious mental illness were almost three times as likely as other mothers without serious mental illness to have come to the attention of the child welfare system or to have lost custody of their children. Regardless of diagnosis, having experienced a psychiatric inpatient episode independently conferred a twofold higher risk of involvement in the child welfare system and a nearly threefold-higher risk of having a child placed in out-of-home-care.

The percentage of mothers with serious mental illness who experienced custody loss in this study was more than four times that of mothers without these disorders. However, this proportion was considerably lower than in previous studies ( 2 , 13 ), which may be related to the fact that previous studies used self-reports to determine lifetime prevalence of custody loss, whereas this study used administrative data to determine involvement in the child welfare system over a five-year period. It may also be that the relationship between a mother's serious mental illness and involvement in the child welfare system has changed over time.

A few study limitations should be mentioned. First, the validity of the algorithm for linking mothers and children in the welfare eligibility files has not been tested. It was based on the assumption that the relationship between the oldest female and children in a given household is that of mother and child. If this assumption is erroneous, it is still unlikely that misidentification of family units would be any higher or lower for mothers with a psychiatric diagnosis than for mothers without a diagnosis. Second, this study relied on Medicaid claims to determine the presence of a psychiatric disorder. At least two studies have found good reliability between research diagnoses and Medicaid claims diagnoses of serious mental illness ( 16 , 17 ); however, it is possible that there were many undiagnosed cases in this sample. If mothers with undiagnosed serious mental illness are also more likely than other mothers to have involvement in the child welfare system, then the study results would provide an underestimate of the relationship between maternal psychiatric illness and involvement in the child welfare system. A third limitation is that important variables that may affect involvement in the child welfare system, especially drug use and social support, were not measured in this study.

Despite these limitations, the findings have important implications. Previous research has shown the lack of coordination between publicly funded mental health systems and child welfare systems; few states have formal coordination mechanisms or even require the collection of information about whether women in treatment have children ( 4 , 7 , 18 ). These results suggest the need to develop appropriate coordination mechanisms to meet the needs of the large proportion of women in mental health treatment who have lost or are at risk of losing custody of their children. Instruments to assess parenting capability of mothers in treatment as well as interventions to improve their parenting skills should be developed.

In addition to the need for coordinated services to address parenting, mothers with serious mental illness may need further support to negotiate the child welfare system. Sands and colleagues ( 14 ) reported that mothers with serious mental illness often expressed confusion about their rights in custody arrangements. Professionals in the mental health system should be aware that mothers with serious mental illness may be at a disadvantage in negotiating parental rights, because of their own lack of resources and because of the perceptions of professionals in the legal and child welfare systems.

Important implications are also related to the temporal ordering of involvement in the child welfare system and mental health treatment. If treatment generally precedes involvement, then it reinforces the need to provide parenting resources to mothers with serious mental illness as part of their treatment. When treatment precedes involvement, it may exacerbate mothers' concerns that treatment will lead to loss of custody, especially because mental health professionals are mandated to report suspected abuse or neglect. This unintended consequence could provide a strong disincentive to obtain treatment among women with mental health needs.

When involvement in the child welfare system precedes treatment, loss of custody may be the impetus for treatment entry, which suggests that earlier referral and treatment of women with mental illness may result in a reduction of involvement in the child welfare system. Involvement preceding treatment would indicate that the child welfare system is an important gateway into care for women in need of treatment. Although the many components of the mental health care system are increasingly recognized, the child welfare system has been thought of as functioning as part of the mental health system for children. The findings of this study suggest that child welfare professionals be considered part of the mental health system for adults as well, as important referrers to care.

Regardless of the reason for the increased contact with the child welfare system among mothers with serious mental illness, the results of this and other studies suggest the urgent need for increased planning and coordination between the child welfare and mental health systems.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by grant H1-33B03-1109 to the UPenn Collaborative on Community Integration from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (Mark Salzer, Ph.D., principal investigator).

1. Ødegärd O: Fertility of psychiatric first admissions in Norway, 1936-1975. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica 62:212-220, 1980Google Scholar

2. Miller L, Finnerty M: Sexuality, pregnancy, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:502-506, 1996Google Scholar

3. Nimganonkar VL, Ward SE, Agarde H, et al: Fertility in schizophrenia: results from a contemporary US cohort. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavica 95:364-369, 1997Google Scholar

4. Miller L: Sexuality, reproduction, and family planning in women with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:623-635, 1997Google Scholar

5. Carty E: Disability and childbirth: meeting the challenges. Canadian Medical Association Journal 159:363-369, 1998Google Scholar

6. Mowbray C, Oyserman D, Bybee D: Mothers with serious mental illness. New Directions for Mental Health Services 88:73-91, 2000Google Scholar

7. Nicholson J, Geller JL, Fisher WH, et al: State policies and programs that address the needs of mentally ill mothers in the public sector. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:484-489, 1993Google Scholar

8. Rudolph B, Larson GL, Sweeny S, et al: Hospitalized pregnant psychotic women: characteristics and treatment issues. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:159-163, 1990Google Scholar

9. Oyserman D, Mowbray C, Meares P, et al: Parenting among mothers with a serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:296-315, 2000Google Scholar

10. Mowbray C, Oyserman D, Bybee D, et al: Parenting of mothers with a serious mental illness: differential effects of diagnosis, clinical history, and other mental health variables. Social Work Research 26:225-240, 2004Google Scholar

11. Hearle J, Plant K, Jenner L, et al: A survey of contact with offspring and assistance with child care among parents with psychotic disorders. Psychiatric Services 50:1354-1356, 1999Google Scholar

12. Sands RG: The parenting experience of low-income single women with serious mental disorders. Families in Society: Journal of Contemporary Human Services 76:86-96, 1995Google Scholar

13. Hollingsworth L: Child custody loss among women with persistent severe mental illness. Social Work Research 28:199-209, 2004Google Scholar

14. Sands R, Koppelman N, Solomon P: Maternal custody status and living arrangements of children of women with severe mental illness. Health and Social Work 29:317-325, 2004Google Scholar

15. Llewellyn G, McConnell D, Ferronato L: Prevalence and outcomes for parents with disabilities and their children in an Australian court sample. Child Abuse and Neglect 27:235-251, 2003Google Scholar

16. Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, et al: Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:69-71, 1992Google Scholar

17. Walkup J, Boyer C, Kellermann S: Reliability of Medicaid claims files for use in psychiatric diagnoses and service delivery. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 27:129-139, 2000Google Scholar

18. Blanch A, Nicholson J, Purcell J: Parents with severe mental illness and their children: the need for human services integration. Journal of Mental Health Administration 21:388-396, 1994Google Scholar