Patterns of Adult Psychotherapy in Psychiatric Practice

Psychotherapy has long been recognized as a key component of psychiatric care. Recently, research findings have demonstrated that for a variety of diagnoses, patients who receive both psychopharmacological treatment and psychotherapy have better outcomes than those who receive psychopharmacologic treatment alone ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ). Additionally, evidence-based practice guidelines for psychiatrists recommend psychotherapy for several disorders as the most effective way to deal with psychosocial issues, treatment adherence, and prevention of relapse ( 8 ).

Despite the expanding evidence base for psychotherapies over the past decade, use of psychotherapy in psychiatric practice has declined in recent years. Olfson and colleagues ( 9 ) found that visits to office-based psychiatrists were less likely to include psychotherapy in 1995 than in 1985. Additionally, a study of outpatient treatment for depression found that the proportion of treated individuals who received psychotherapy declined significantly from 1987 to 1997 ( 10 ).

Several explanations for the decline in psychotherapy by psychiatrists have been offered. For example, there has been an increase in pharmacological options available to physicians in the treatment of mental disorders and greater public acceptance of pharmacological treatments, both of which could contribute to a decrease in psychotherapy use ( 10 , 11 ). Also, the growth and changes in financing and managed care have led some clinicians to express concerns that psychotherapy in the current health care environment is endangered, with managed care companies focusing on short-term psychotherapy provided by other mental health professionals ( 12 , 13 , 14 ). In addition, significant financial disincentives inherent in fee structures for providing psychotherapy over medication management alone have been documented ( 15 ), and there has been an overall reduction in mental health benefits provided by managed care organizations ( 12 ).

This study addressed these issues and aimed to examine the patterns and types of psychotherapy provided by psychiatrists and other mental health providers in routine psychiatric practice settings in the United States. It also compared patients of psychiatrists who receive psychotherapy with those who do not and examined the predictors of receipt of psychotherapy, specifically factors related to the patient's sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, the health plan, and the psychiatrist's characteristics and practice setting.

Methods

Data source

A national sample of 615 psychiatrists participating in the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education (APIRE) Practice Research Network's (PRN) 1999 Study of Psychiatric Patients and Treatments (SPPT) provided sociodemographic, clinical, diagnostic, treatment, and health plan data on a systematic sample of 1,843 patients. Each psychiatrist completed a 24-item data collection instrument for three randomly selected patients. Pincus and colleagues ( 16 ) have provided a detailed description of network recruitment and membership, survey design and implementation, patient sampling, and data validation studies for the 1997 SPPT. The same methods were used for the 1999 SPPT. Analytic comparisons of 78 sociodemographic and practice variables—for example, sex, age, and practice variables, such as setting and patients' type of health plan—have shown that PRN members are representative of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) membership as a whole. At the time of the study, the APA membership represented a majority of psychiatrists in the United States. Only four variables showed statistically significant differences: APA members were more likely to be board certified in geriatric psychiatry and affiliated with a medical school, whereas non-APA members were more likely to be residing in the Midwest and of "other" or mixed race. These differences were taken into account when calculating sampling weights.

The 1999 SPPT targeted all 784 PRN members who spent at least 15 hours per week in direct patient care. The PRN included 378 randomly selected and recruited psychiatrists to ensure representativeness across treatment settings; the remainder were self-selected volunteers recruited nationally by the APA and local district branches. A total of 615 PRN members participated in the 1999 SPPT (response rate of 78 percent). Each participant was assigned a random start day and time and asked to complete a patient log for the next 12 consecutive patients for whom face-to-face treatment was provided. Participants provided clinically detailed data on three systematically preselected patients from the patient log, collectively providing data for 1,843 patients. These analyses were limited to patients aged 18 years and older, resulting in a sample of 587 psychiatrists reporting on 1,589 patients.

Sampling weights

Weights were developed that adjusted for differences between PRN and APA members because of oversampling of younger psychiatrists and those from a racial or ethnic minority group and survey nonresponse. Data on demographic characteristics, training, and practice setting from the APA membership database and APIRE's 1998 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice were used in developing weights. Stabilization of weights at each stage of weight development reduced the effect of outliers ( 16 , 17 ). SUDAAN software was used to weight the data and to adjust for the nested sampling design in order to generate nationally representative estimates reflective of the APA membership ( 18 ).

Measures

Patients were considered to have received psychotherapy if the psychiatrist indicated that he or she or another provider had provided psychotherapy in the past 30 days. Therefore, some analyses for this study refer to psychotherapy provided to patients of psychiatrists by the psychiatrist or another provider and some refer to psychotherapy provided by the psychiatrist only. Other measures used in this study, including patient and psychiatrist sociodemographic information, clinical factors, and health plan factors are described below. Less than 2 percent of the data were missing for any variable, with the exception of patient's education and work status (approximately 8 percent each).

Analytic plan

Weighted bivariate statistical tests using the Wald chi square statistic (or test) assessed differences in rates of psychotherapy across patient sociodemographic characteristics, diagnosis and clinical factors, practice settings, health plans, and characteristics of the psychiatrist. Pairwise contrasts were used to test for significance between multiple levels of variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis explored the association between the aforementioned factors with receipt of psychotherapy, after statistically adjusting for other variables in the model. This type of analysis allowed for observation of the independent association of each variable with receipt of psychotherapy, while the analysis controlled for the potentially confounding effects of other variables in the model.

Results

Sample description

Psychiatrists in the sample were mostly male (422 psychiatrists, or 72 percent) and white (458 psychiatrists, or 78 percent); 18 (3 percent) were African American, 40 (7 percent) were Hispanic, and 70 (12 percent) were from another racial or ethnic group. The mean±SD age of the psychiatrists was 51±11 years; 170 (29 percent) were younger than 45 years, 346 (59 percent) were between the ages of 45 and 64 years, and 71 (12 percent) were older than 65 years. They had an average of 57 patient visits in a typical work week.

Patients were mostly female (893 patients, or 56 percent) and white (1,261 patients, or 79 percent); 151 (10 percent) were African American, 101 (6 percent) were Hispanic, and 75 (5 percent) were from another racial or ethnic group. A total of 836 patients (53 percent) had more than a high school education, and 217 (14 percent) had less than a high school education. The mean age of the patients was 45±15 years, and most were between the ages of 25 and 64 years (1,287 patients, or 81 percent). A total of 703 (44 percent) were employed in full- or part-time jobs, and 524 (33 percent) were not working because of physical or mental disability. The most common primary diagnosis in the sample was major depression (625 patients, or 39 percent), followed by schizophrenia (252 patients, or 16 percent) and anxiety disorders (193 patients, or 12 percent). Patients had been in treatment for a mean of 30±44 months.

Patterns and types of psychotherapy provided

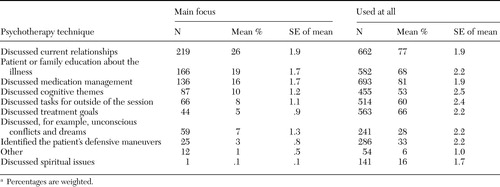

Psychiatrists reported that nearly two-thirds of patients received some form of psychotherapy (1,045 patients, or 66 percent) from the physician or another provider in the past 30 days: 890 (56 percent) received psychotherapy from the psychiatrist and 155 (10 percent) received it from another practitioner. These findings are not consistent with previous studies showing that patients of psychiatrists were more likely to receive care from a clinician other than the psychiatrist ( 19 ). However, this previous research examined only patients in a national managed mental health care organization, as opposed to our study which examined patients across a full range of settings. As shown in Table 1 , the most commonly reported therapeutic techniques used by psychiatrists were discussion of medication management issues (693 patients, or 81 percent), discussion of current relationships (662 patients, or 77 percent), and education of the patient or family about the illness (582 patients, or 68 percent); discussion of current relationships was most often cited as the main focus of therapy.

|

Table 1 Techniques used in psychotherapy provided in the past 30 days to 1,045 adult patients of 587 psychiatrists a

a Percentages are weighted.

Factors associated with receipt of psychotherapy

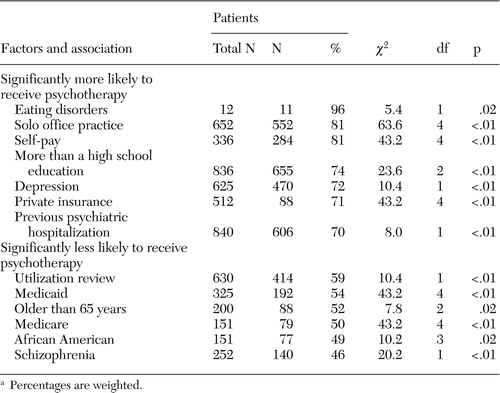

As shown in Table 2 , patients who were African American or older than 65 years were less likely than patients who were white, Hispanic, or younger than 65 years to receive psychotherapy. Patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were significantly less likely than those without such a diagnosis to receive psychotherapy (140 patients, or 46 percent, compared with 970 patients, or 70 percent). It is important to note that patients with more severe psychotic symptoms were less likely than those with mild to moderate psychotic symptoms to receive psychotherapy (44 patients, or 33 percent, compared with 188 patients, or 62 percent). Patients whose care was subjected to utilization review were significantly less likely than those whose care was not subject to such a review to receive psychotherapy (414 patients, or 59 percent, compared with 699 patients, or 70 percent).

|

a Percentages are weighted.

As shown in Table 2 , patients with more than a 12th grade education were more likely than those with a high school education or less to receive psychotherapy. Also, patients with eating disorders or major depression were significantly more likely than those without those diagnoses to receive psychotherapy. Patients whose main sources of payment were private insurance or self-pay were significantly more likely than patients who used Medicaid or Medicare to receive psychotherapy. Patients who were treated in solo office practices were significantly more likely than patients treated in any other setting to receive psychotherapy. Also, those with a previous psychiatric hospitalization were more likely to receive psychotherapy.

Logistical regression analyses were conducted to examine the independent association of factors in the model with receipt of psychotherapy when the analysis adjusted for the other factors in the model. Logistical regression analyses found that patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were significantly less likely than those without such a diagnosis to receive psychotherapy (odds ratio [OR]=.6, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=.4 to 1.0). Patients with a diagnosis of an eating disorder were significantly more likely than those without such a diagnosis to receive psychotherapy (OR=8.3, CI=2.2 to 31.3). In addition, the number of axis I (OR=1.4, CI=1.0 to 2.0) and axis IV problems (OR=1.2, CI=1.0 to 1.3) were positively related to the receipt of psychotherapy. Patients whose care was subjected to utilization review were significantly less likely than those whose care was not to receive psychotherapy (OR=.6, CI=.4 to .9). The age and gender of the treating psychiatrist and the treatment setting were not significantly independently associated with provision of psychotherapy.

Discussion

Results indicate that more than one-third of patients did not receive psychotherapy from the responding psychiatrist or another provider in the past 30 days, and more than half of all patients with schizophrenia did not receive psychotherapy in the past 30 days. However, patients with mild to moderate psychotic symptoms were more likely than those with more severe psychotic symptoms to receive psychotherapy. Also, nearly half of patients who used Medicaid or Medicare as their main source of payment did not receive psychotherapy. In our study of patients across a full range of treatment settings, most patients who received psychotherapy received it from their psychiatrist and not from another clinician, contrary to previous findings that examined only patients in a national managed mental health care organization ( 19 ). Findings from the logistical regression were reassuring in showing that patients with the greatest clinical complexity and higher levels of psychosocial problems were most likely to receive psychotherapy. However, it was troubling to see that utilization review, which one would hope would be associated with increased rates of treatment, was associated with significantly lower odds of receiving psychotherapy.

Although, psychotherapy has historically played a central role in psychiatric care, several changes in health care financing, the psychiatric workload, pharmacological treatment options, and administrative requirements associated with psychiatry have contributed to its declining use in psychiatric practice. For example, a recent study showed that psychiatrists who provided a 45 to 50 minute outpatient psychotherapy session earned 40.9 percent less than if they provided three 15-minute medication management visits ( 14 ). One reason for the financial disincentives for psychotherapy may be that third-party payers perceive psychopharmacologic treatments as being more effective than psychotherapy ( 20 ).

Changes in the psychiatric workload may contribute to the psychotherapy trends. A recent study found that over the past decade psychiatrists are spending less time in direct patient care activities and more time in administrative activities ( 21 , 22 ). At the same time, psychiatrists are seeing a higher mean number of patients each week. Because psychotherapy is more time-intensive than medication management services, it is possible that psychiatrists have provided more medication management services as opposed to psychotherapy to meet the demands of their increased patient caseload and decreased time in direct patient care.

Changes in treatment options available to psychiatrists and patient preferences may also influence the trends in psychotherapy use. With the introduction of drugs such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, with fewer side effects and simpler dosing regimens, medication interventions have become more attractive ( 10 ). The general public has become more accepting of pharmacological interventions for mental illness, in part because of advertising efforts by the pharmaceutical industry ( 11 , 23 , 24 ). Consequently, patients may be more likely to demand or prefer medications.

This study has several limitations. First, our data were collected in 1999. Several significant changes have been made in behavioral health care in the years since it was conducted, such as the organization and financing of care ( 25 , 26 ), and they should be considered in interpreting these results. Also, our data rely on the self-reporting of psychiatrists, with no true measures of quality or fidelity to psychotherapy treatment models. Although high rates of evidence-based therapies (for example, cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy) were reported, few psychiatrists have been formally trained in these models ( 27 ), even though many of the evidence-based treatment guidelines specifically recommend these psychotherapies. Consequently, access to these psychotherapies is likely to be significantly lower than our findings suggest. Additionally, because of power limitations, we were unable to examine provision of specific psychotherapies—for example, cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic therapy. Instead, we grouped all psychotherapies together for these analyses, which may obscure potential differences in the provision of different types of psychotherapies or psychotherapy to different patient groups.

Also, our data do not indicate whether psychotherapy was provided before the past 30 days or was refused by the patient. In addition, this study examined only patients treated by psychiatrists. However, with the majority of psychotherapy in the United States performed by nonpsychiatrists ( 19 ), data on whether psychotherapy was provided by nonpsychiatrists to these patients were also collected. Nonetheless, patients of psychiatrists are of particular interest given psychiatrists' role in treating persons with severe mental illness ( 28 ) and in providing psychopharmacologic treatments, which have become increasingly important in the treatment of psychiatric disorders.

Conclusions

Future research should examine the quality of psychotherapy provided to patients of psychiatrists and the fidelity to psychotherapy models. Specifically, measurement of the gap between psychiatrists who have been trained in these models and the number of psychiatrists who use these models may point out the need for further training. Additionally, research examining correlates and implications of this pattern of provision of psychotherapy is needed. Not providing psychotherapy could result in significantly poorer functioning and treatment outcomes for patients as well as diminished cost-effectiveness of care provided. These findings would be useful in informing health care financing policy and services delivery models to enhance provision of psychotherapies.

Acknowledgments

These analyses have been generously supported by funding from the American Psychiatric Foundation. Practice Research Network (PRN) psychiatrists contributed their time to participate in the 1999 PRN Study of Psychiatric Patients and Treatments study.

1. Keller MB, McCullough JP, Klein DN, et al: A comparison of nefazodone, the cognitive behavioral-analysis system of psychotherapy, and their combination for the treatment of chronic depression. New England Journal of Medicine 342:1462-1470, 2000Google Scholar

2. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Google Scholar

3. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, et al: Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:2529-2536, 2000.Google Scholar

4. Mavissakalian M: Combined behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy of agoraphobia. Journal of Pediatric Research 27:179-191, 1993Google Scholar

5. Clarkin JF, Carpenter D, Hull J, et al: Effects of psychoeducational intervention for married patients with bipolar disorder and their spouses. Psychiatric Services 49:531-533, 1998Google Scholar

6. Reducing Tobacco Use: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, Ga, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2000Google Scholar

7. Kool S, Dekker J, Duijens IJ, et al: Efficacy of combined therapy and pharmacotherapy for depressed patients with or without personality disorders. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 11:133-141, 2003Google Scholar

8. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. American Journal of Psychiatry 161 (suppl 2):1-56, 2004Google Scholar

9. Olfson M, Marcus S, Pincus H: Trends in office-based psychiatric practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:451-457, 1999Google Scholar

10. Olfson M, Marcus S, Druss B: National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA 287:203-209, 2002Google Scholar

11. Langer F: Use of anti-depressants is a long-term practice. Apr 10, 2000. Available at http://abcnews.go.com/onair/worldnewstonight/poll000410.htmlGoogle Scholar

12. Clemens NA, MacKenzie KR, Griffith JL, et al: Psychotherapy by psychiatrists in a managed care environment: must it be an oxymoron? A forum from the APA Commission on Psychotherapy by Psychiatrists: American Psychiatric Association. Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 10:53-62, 2001Google Scholar

13. Regestein QR: Psychiatrists' views of managed care and the future of psychiatry. General Hospital Psychiatry 22:97-106, 2000Google Scholar

14. Guze SB: Psychotherapy and managed care. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:561-562, 1998Google Scholar

15. West JC, Wilk JE, Rae DS, et al: Financial disincentives for the provision of psychotherapy. Psychiatric Services 54:1582-1583, 2003Google Scholar

16. Pincus HA, Zarin DA, Tanelian TL, et al: Psychiatric patients and treatments in 1997: findings from the American Psychiatric Practice Research Network. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:441-449, 1999Google Scholar

17. Zarin DA, Pincus HA, Johnson JL, et al: Characterizing psychiatry with findings from the 1996 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:397-404, 1998Google Scholar

18. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Hunt PN, et al: SUDAAN User's Manual, Release 7.0. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1996Google Scholar

19. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Cuffel B, et al: Outpatient utilization patterns of integrated and split psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Psychiatric Services 49:477-482, 1998Google Scholar

20. Sharfstein SS, Goldman H: Financing the medical management of mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 146:345-349, 1989Google Scholar

21. Wilk JE, Regier DA, West JC, et al: Current status of the psychiatry workforce in the US. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, San Francisco, May 17-21, 2003Google Scholar

22. Scully JH, Wilk JE: Selected characteristics and data of psychiatrists in the United States, 2001-2002. Academic Psychiatry 27:247-251, 2003Google Scholar

23. Nikelly AG: Drug advertisements and the medicalization of unipolar depression in women. Health Care for Women International 16:229-242, 1995Google Scholar

24. Goldman R, Montagne M: Marketing "mind mechanics": decoding antidepressant drug advertisements. Social Science Medicine 22:1047-1058, 1986Google Scholar

25. Wilk J, Duffy FF, West JC, et al: Perspectives on the future of the mental health disciplines, in Mental Health, United States, 2002. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. DHHS pub no SMA-3938. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004Google Scholar

26. Mark TL, Coffey RM, Vandivort-Warren R, et al: MHSA Spending Estimate Team: US spending for mental health and substance abuse treatment, 1991-2001. Health Affairs, Web exclusive, Mar 29, 2005. Available at http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/hlthaff.w5.133/dc1Google Scholar

27. Weissman M: Access to evidence-based psychotherapies. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, New York, May 1-6, 2004Google Scholar

28. Pingitore DP, Scheffler RM, Sentell T, et al: Comparison of psychiatrists and psychologists in clinical practice. Psychiatric Services 53:977-983, 2002Google Scholar