Racial Disparities in the Use of Second-Generation Antipsychotics for the Treatment of Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Despite recommendations that second-generation antipsychotics be used as first-line treatment for schizophrenia, previous studies have shown that blacks are less likely than whites to receive these newer drugs. This study determined the rate at which second-generation antipsychotics were prescribed to whites and blacks with schizophrenia who were treated as outpatients. METHODS: Data were collected from a community mental health clinic affiliated with an academic center in Rochester, New York. Multivariate logistic regression was used to examine the association between race and the receipt of a second-generation antipsychotic. RESULTS: Data were available for 456 patients: 276 whites and 180 blacks. Ninety-five percent received a second-generation antipsychotic. Whites were approximately six times more likely than blacks to receive a second-generation medication, after the analysis controlled for clinical and sociodemographic factors (p<.001). Most of this difference appeared to be driven by a disparity in the use of clozapine. CONCLUSIONS: In this sample, blacks were less likely than whites to receive second-generation antipsychotics, demonstrating a persistent gap in the quality of care for patients with schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is a potentially debilitating and lifelong mental illness, and treatment has presented numerous challenges. Although the mainstay of treatment for patients with schizophrenia has been antipsychotic medications, first-generation antipsychotics can cause side effects as unpleasant and debilitating as the illness symptoms. Since 1989 second-generation antipsychotics have been available as an alternative to first-generation drugs. Second-generation antipsychotics are at least as effective as first-generation antipsychotics in controlling the positive symptoms of psychotic disorders, may be more effective in controlling the negative symptoms and cognitive impairments, and have more favorable side effect profiles (1,2,3,4). Currently, these newer antipsychotics are recommended as first-line treatment for schizophrenia (3,5).

Despite the treatment guidelines, the rate at which second-generation antipsychotics are prescribed for black patients has lagged behind the rate at which these same drugs are prescribed for white patients. Previous studies have shown that although as many as 85 percent of white patients who are given an antipsychotic receive a second-generation drug, black patients are approximately only two-thirds as likely to receive these newer medications (1,6,7). However, because previous studies have generally been conducted in community-based settings, little is known about prescribing practices in academic settings.

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to determine whether the rates at which second-generation antipsychotics are prescribed to black and white patients differed among patients who were given a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and were being treated at an academic medical center. We hypothesized that black patients would be less likely than white patients to receive second-generation antipsychotics and that sociodemographic and clinical factors would help to explain any observed racial variations in the use of these drugs.

Methods

Before the initiation of data collection, approval for this study was obtained from the research subjects review board of the University of Rochester. Patients were identified through an administrative database at an academic center in Rochester, New York. This database includes data for all patients treated at the academic center. Eligible patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (DSM-IV code 295.xx); had a known race of either African American or Caucasian, non-Hispanic; were treated in 2003, 2004, or both; and were at least 18 years old.

A vast majority of patients treated for schizophrenia in the academic center are treated through the associated community mental health center, and many obtain their prescriptions from the center's pharmacy. The pharmacy records were queried for all patients who were identified through the academic center's administrative database. Data from the administrative database and the pharmacy database were merged for analysis.

Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, race, education, marital status, income source, living arrangement, and insurance. Race was either self-identified or clinician designated. Clinical variables included DSM-IV diagnosis and presence or absence of a concomitant substance use disorder. Antipsychotic medications were classified as first or second generation. Second-generation antipsychotics were defined as medications that were approved by the Food and Drug Administration after 1988. All sociodemographic variables were collected from the academic center's administrative database, with the exception of insurance, which was collected from the pharmacy database. The research question was addressed by using multivariate logistic regression to test the relationship between race and the receipt of a second-generation antipsychotic. Sociodemographic factors that have been described in similar studies—age, gender, education, and insurance—were included in the model.

During data collection, it became evident that a vast majority of patients were receiving a second-generation antipsychotic, either alone or in combination with a first-generation antipsychotic (433 patients, or 95 percent). It was also noted that almost one-quarter of patients had been given a prescription for clozapine (109 patients, or 24 percent). On the basis of these unexpected observations, the investigators planned a secondary analysis to examine prescription patterns more closely. For the secondary analysis, clozapine was considered to be unique from both first- and second-generation antipsychotics. Although clozapine is considered to be the prototypical second-generation antipsychotic, physicians may be less likely to prescribe clozapine to black patients because of the perceived heightened risks of diabetes and agranulocytosis (8). For the secondary analysis, multivariate logistic regression modeled the likelihood of receiving clozapine, with or without other antipsychotic medications. Patients who received only a first-generation antipsychotic were excluded from this analysis. The same covariates that were used in the primary analysis were included in the secondary analysis.

In all analyses, missing data were treated as a unique response category, and tests were two-sided with alpha=.05. Analyses were conducted by using SAS version 8.02.

Results

From the administrative database, 681 patients were identified as being eligible for our study. Prescription data were available for 456 of these patients (67 percent); these 456 patients constituted our sample. In our sample, most patients were male (295 patients, or 65 percent), were white (276 patients, or 61 percent), had never been married (350 patients, or 77 percent), and were insured by Medicaid (404 patients, or 89 percent). The mean±SD age of the sample was 43.1±11.3 years. Information about education, income source, and living situation was missing for more than one-third of the patients. One-third of patients (166 patients, or 36 percent) had a co-occurring substance use disorder. The patients for whom prescription data were not available did not differ appreciably from the study sample, although they were more likely to be female (χ2=5.3, df=1, p=.02) and were less likely to have a substance use disorder (χ2=7.8, df=2, p=.02). Patients for whom prescription data were not available were also slightly older, with a mean age of 45.6± 12.2 years (t=2.67, df=679, p=.008).

In bivariate analysis, race was strongly associated with the receipt of any second-generation antipsychotic (χ2=14.8, df=1, p<.001). To further elucidate the relationship between race and medication, seven possible treatment regimens were identified, using all the combinations of first- and second-generation antipsychotics and clozapine. Results of the Fisher's exact test confirm that race was significantly associated with treatment regimen (p<.001).

Although white patients and black patients had a similar probability of receiving a second-generation antipsychotic alone (171 white patients, or 62 percent, compared with 113 black patients, or 63 percent), black patients were more likely to receive a first-generation antipsychotic alone (six white patients, or 2 percent, compared with 19 black patients, or 11 percent). Also, black patients were more likely to receive a second-generation antipsychotic in combination with a first-generation antipsychotic (18 white patients, or 7 percent, compared with 13 black patients, or 13 percent). Furthermore, white patients were more likely to receive clozapine alone (51 white patients, or 19 percent, compared with 18 black patients, or 10 percent) or in combination with another second-generation antipsychotic (22 white patients, or 8 percent, compared with four black patients, or 2 percent). Receipt of a second-generation antipsychotic was not associated with any covariate, including diagnosis, age, gender, insurance status, education, marital status, income source, living situation, or concomitant substance use disorder.

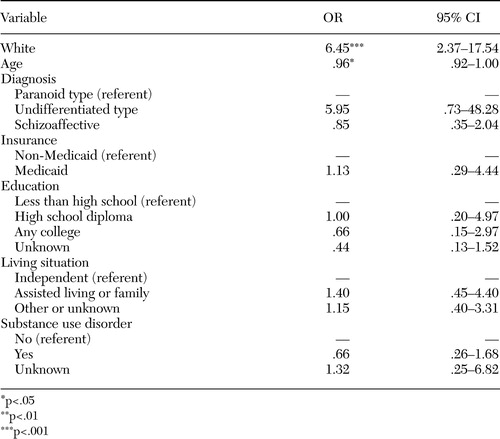

Logistic regression with SAS "proc logistic" (9) was used to model the association between race and the receipt of any second-generation antipsychotic (Table 1). Covariates were the variables that were significantly associated with race in bivariate analyses, including diagnosis, insurance status, age, education, living situation, and substance use disorder. The adjusted odds ratio (OR) for the relationship between race and the receipt of a second-generation antipsychotic was 6.45 (p<.001), indicating that white patients were approximately six times more likely than black patients to receive a second-generation antipsychotic. The only covariate associated with the receipt of a second-generation antipsychotic was age; older patients were less likely than younger patients to receive a second-generation antipsychotic (p=.03).

Logistic regression was next performed to examine the association between race and the receipt of clozapine. White patients were more than twice as likely as black patients to receive clozapine (OR=2.70, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.58 to 4.63, p<.001). Additionally, compared with patients who were living independently, those who were living in an assisted living facility, in a group home, or with friends or family were twice as likely to receive clozapine (OR=2.05, CI=1.09 to 3.84, p=.03). Finally, patients whose substance use disorder status was unknown were more likely to receive clozapine (OR=2.88, CI=1.35 to 6.16, p=.007), although the clinical significance of this finding is unclear.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that in an academic medical setting, black patients were less likely than white patients to receive second-generation antipsychotics, even after the analysis controlled for potential confounding factors, such as education and insurance status. This finding is consistent with previous work that has demonstrated such disparities in nonacademic settings (1,6). The clinical significance of our finding is somewhat unclear, because most patients in our sample received a second-generation antipsychotic. However, 10 percent of the black patients in our sample received only first-generation drugs, so there appears to be a genuine gap in the quality of care based on patient race.

Among patients who received a second-generation antipsychotic, whites were more than twice as likely as blacks to receive a regimen that included clozapine. This finding is not surprising, because previous work has consistently shown that black patients are less likely than white patients to be given a prescription for clozapine and more likely to have clozapine therapy discontinued (10). Such a difference may be due to greater perceived risks of clozapine-induced diabetes and agranulocytosis among black patients (10). Although second-generation antipsychotics in general are associated with increased risk of diabetes, recent consensus guidelines have suggested that clozapine is associated with a high degree of risk relative to other drugs (5). It may be beneficial for future studies of this issue to control for concurrent diagnosis of diabetes and depressed baseline granulocyte counts. However, it is also important to note that pharmacologic evidence suggests that black patients may have lower baseline white blood cell and neutrophil counts, and that such benign leukopenia is not necessarily indicative of a higher risk of agranulocytosis (8,11). Consideration should be given to the development of new guidelines for the use and discontinuation of clozapine (11), because current guidelines may unnecessarily deny black patients access to a medication that is regarded as the most effective antipsychotic available (2,4).

A major limitation of this study is that prescription data were not available for all patients. Although patients with and without prescription data appeared to be quite similar, patients for whom prescription data were available were more likely to be male and to have a substance use disorder. Because no evidence suggests that gender is associated with use of second-generation antipsychotics, this difference is unlikely to bias our findings. However, differences in the rate of substance use disorder may introduce a bias, because the black patients in our sample were more likely than the white patients to have a substance use disorder (data not shown) and it has been demonstrated that physicians prefer to prescribe first-generation antipsychotics for such patients (6). Thus the observed difference between races in use of second-generation antipsychotics may be a result of a difference in rates of substance use disorders. The strength of the association between race and prescription type decreases the chance that this association is due solely to residual confounding. Furthermore, both the group of patients for whom prescription data were available and the group for whom data were not available had a fairly heterogeneous mix of patients who did and did not have a substance use disorder. Thus the multivariate analysis should control for most of the effect of confounding.

Because we did not collect prescription history, we do not know whether patients who received only first-generation antipsychotics during the study period may have received second-generation antipsychotics in the past. However, it is unlikely that patients who were once given a prescription for a second-generation drug would have it switched to a first-generation drug. Even if this practice were common, it would present a bias only if the practice were more or less common for black patients. No current evidence suggests that this practice occurs, but this issue may warrant further investigation.

Data were missing for many of the observations in our data set, presenting another possible bias. Observed differences between racial groups were in the direction expected (for example, black patients had fewer years of education), suggesting that missing values were fairly random. Finally, sampling bias may have been introduced because individuals whose race was unknown were excluded. Because race was missing for less than five percent of patients in the administrative database, exclusion of these patients is unlikely to have significantly biased our results.

Only one previous study has examined prescription patterns of second-generation antipsychotics in an academic setting (12). That study, by Arnold and colleagues, examined racial disparities in the use of second-generation antipsychotics in a university hospital. Notably, Arnold and colleagues' study found that black patients were as likely as white patients to receive second-generation drugs. Several possibilities can explain the difference between our results and those of Arnold and colleagues. First, the study by Arnold and colleagues used data from inpatients, whereas our study used data from outpatients. Physicians' prescribing preferences may differ in the acute setting and in the management setting. Second, the sample size for Arnold and colleagues' study (N=167) may have been insufficient to detect a true difference between racial groups. Finally, differences between the two studies may reflect true variations in prescribing patterns. Although treatment guidelines for schizophrenia are available and regularly updated, physicians may rely on their own experience or the conventions of their practice setting. Physicians' adherence to American Psychiatric Association guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia has not been measured and presents an interesting question for future research.

Conclusions

Our findings are consistent with a large body of literature demonstrating that black patients receive lower-quality medical care compared with white patients (13). However, our study leaves open the question as to what is the driving factor behind these observed disparities. If black patients with schizophrenia indeed experience a different symptom profile than white patients, then such differences may warrant racially based treatment approaches. However, a more probable scenario is that physicians perceive patient symptoms differently on the basis of the patient's race. In this case, physicians should be encouraged to use standardized diagnostic and symptom evaluation tools, which can reduce bias and equalize care between racial groups (14). It will also be important for future studies to identify specific factors—including patient behaviors, illness characteristics, physician beliefs, and patient or physician preferences—that are likely to lead to disparities in care. Ultimately, findings from such research should be used to educate physicians and other health care providers. Raising awareness about specific health disparity issues may prompt clinicians to examine their own behaviors and may ultimately promote more thoughtful care.

Ms. Mallinger was affiliated with the department of community and preventive medicine at the University of Rochester in Rochester, New York, at the time that this research was conducted. Dr. Fisher and Dr. Brown are with the department of community and preventive medicine, and Dr. Lamberti is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Rochester. Send correspondence to Ms. Mallinger, care of Ellen Apollonio, 300 Crittenden Boulevard, Rochester, New York 14642 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Logistic regression modeling of the receipt of any second-generation antipsychotic among 276 white patients and 180 black patients who were treated for schizophrenia at a community mental health clinic affiliated with an academic center

1. Daumit GLM, Crum RMM, Guallar EM, et al: Outpatient prescriptions for atypical antipsychotics for African Americans, Hispanics, and whites in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:121–128,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Worrel JA, Marken PA, Beckman SE, et al: Atypical antipsychotic agents: a critical review. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 57:238–255,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Dawkins K, Lieberman JA, Lebowitz BD, et al: Antipsychotics: past and future. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:395–405,1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Davis JM, Chen N, Glick ID: A meta-analysis of the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:553–564,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, et al: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1–56,2004Link, Google Scholar

6. Mark TL, Dirani R, Slade E, et al: Access to new medications to treat schizophrenia. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 29:15–29,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kreyenbuhl J, Zito JM, Buchanan RW, et al: Racial disparity in the pharmacological management of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:183–193,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Lawson WB: Clinical issues in the pharmacotherapy of African-Americans. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 32:275–281,1996Medline, Google Scholar

9. SAS Language Reference, Version 8, Cary, NC, SAS Institute, Inc, 1999Google Scholar

10. Moeller FG, Chen YW, Steinberg JL, et al: Risk factors for clozapine discontinuation among 805 patients in the VA hospital system. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 7:167–173,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Fisher N, Baigent B: Treatment with clozapine. British Medical Journal 313:1262,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Arnold LM, Strakowski SM, Schwiers ML, et al: Sex, ethnicity, and antipsychotic medication use in patients with psychosis. Schizophrenia Research 66:169–175,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Snowden LR: Bias in mental health assessment and intervention: theory and evidence. American Journal of Public Health 93:239–243,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Neighbors HW, Trierweiler SJ, Munday C, et al: Psychiatric diagnosis of African Americans: diagnostic divergence in clinician-structured and semistructured interviewing conditions. JAMA 91:601–612,1999Google Scholar