Baseline Predictors of Serious Adverse Events at One Year Among Patients With Bipolar Disorder in STEP-BD

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Little is known about serious adverse events that occur in the context of clinical care for bipolar disorder. This study examined predictors of serious adverse events in a large cohort of patients with bipolar disorder. METHODS: Types and frequency of serious adverse events were tabulated on the basis of data from the first 1,000 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). STEP-BD follows a large cohort of patients longitudinally. Treatments are provided as deemed most appropriate by the treating psychiatrist. Logistic regression was used to identify variables present at study entry that were associated with the occurrence of a serious adverse event within one year. RESULTS: A total of 161 serious adverse events were reported among 118 participants. The most frequent serious adverse event was hospitalization for suicidal ideation (44 participants, or 27 percent). A greater number of previous psychiatric medications was predictive of the occurrence of a psychiatric serious adverse event among participants who had less than one year of study follow-up data. A history of psychosis, current substance abuse, lower household income, and a fully syndromic baseline mood state were associated with the occurrence of a psychiatric serious adverse event among participants who had one full year of follow-up data. CONCLUSIONS: These data identify clinical and demographic factors that warrant closer clinical follow-up, because these factors may be predictive of poor outcomes in the following year, even in the context of expert care.

Chronic psychiatric disorders are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, including functional disability, poor outcomes of concurrent medical illnesses (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10), suicide attempt and completion, and psychiatric hospitalization. Several studies have attempted to identify correlates of adverse outcomes among persons with psychiatric disorders. For example, low socioeconomic status (11), low treatment compliance (12,13), the presence of comorbid substance abuse (13), and a history of numerous psychiatric hospitalizations (14,15,16,17) have been identified as risk factors for rehospitalization among persons with chronic mental illnesses. The data on correlates of adverse events among persons with bipolar spectrum illnesses are somewhat limited.

In the study reported here, we determined the frequency of serious adverse events in a cohort of 1,000 patients with bipolar disorder who were prospectively treated for up to one year as part of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). We also explored clinical and demographic factors that were present at study entry that were associated with the occurrence of a serious adverse event during the first year of study participation.

Methods

STEP-BD is a multicenter project, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, designed to evaluate the longitudinal outcome of patients with bipolar disorder. To enter STEP-BD, patients are required to be at least 15 years of age and to meet DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymia, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar subtype. Exclusion criteria are limited to unwillingness or inability to comply with study assessments and inability to give informed consent. Each study site obtained approval from its respective institutional review board, and written informed consent was obtained for all participants.

STEP-BD clinicians perform structured interviews and assign one of eight operationally defined clinical states as the current clinical status at each clinic visit. Four clinical states correspond to DSM-IV definitions for major depressive, manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes. Patients who achieve relative euthymia (no more than two moderate symptoms) for at least a week are assigned a status of "recovering"; those who sustain euthymia for at least eight weeks are assigned a status of "recovered." Two subsyndromal states (having at least three moderate symptoms but without meeting full criteria for a mood episode) are used to categorize patients as either "continued symptomatic" (when a subsyndromal state follows an acute mood episode) or "roughening" (when a subsyndromal state occurs after a period of recovery from the most recent mood episode).

Investigators at all study sites received extensive standardized training and met certification requirements on all study measures and assessment tools, including rigorous procedures for establishing interrater agreement with benchmark ratings. A detailed discussion of the STEP-BD study methods and baseline clinician and self-rated instruments has been published elsewhere (18).

The population for the study reported here comprised the first 1,000 participants who entered the STEP-BD study. For our analyses, participants were divided into three groups according to the degree of completeness of the data through their first year after study entry: patients who had baseline data only, patients who had less than one year of data, and patients who had one year of data. Original data for this study were collected between November 1999 and April 2002.

A serious adverse event was defined, a priori, as an event that is fatal, life-threatening, disabling or incapacitating; requires or prolongs hospitalization; is a congenital anomaly in the offspring of a participant; or jeopardizes the participant or necessitates an intervention to prevent one of the aforementioned outcomes.

Information about the occurrence of serious adverse events was obtained from Data Safety Monitoring Board reports. Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics were compared across the three study groups outlined above. Chi square or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical variables, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous variables. The remaining analyses were performed for the participants who had one year of data and those who had less than one year of data.

Potential predictors of a serious adverse event were examined by using a logistic regression model, starting with bivariate models examining each independent baseline clinical or demographic variable as a potential predictor of the occurrence of a subsequent serious adverse event within one year of study participation and building toward an exploratory model.

The independent variables examined include age, race, gender, marital status, household income, employment status, level of education, medical insurance status, age at onset of bipolar illness, duration of illness, bipolar subtype, number of psychotropic medications (current and past), number of mood episodes (lifetime depressive episodes and lifetime manic and hypomanic episodes), longest period of remission, history of rapid cycling, suicidal ideation at study entry, comorbid axis I diagnoses (total number, any anxiety disorder, any eating disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and substance use disorder), psychosis (past and current), suicide (past attempt and severity of suicidal ideation within one week of study entry), mean Beck Anxiety Inventory score, mean Beck Hopelessness Scale score, mean NEO [Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness] Five Factor Inventory Subscale scores (agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness), mean Dysfunctional Attitude Scale score, family psychiatric history (bipolar disorder, other mood disorder, substance use disorder, and suicide attempt or completion), presence of rapid cycling, and baseline mood state (operationally defined clinical status).

Results

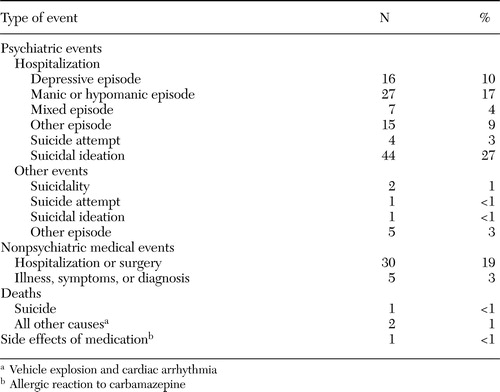

The types and frequency of serious adverse events are shown in Table 1. Of the 1,000 study participants examined, 118 (12 percent) had at least one serious adverse event through the one-year study period. Specifically, 89 participants (9 percent) had one serious adverse event, and 22 (2 percent) had two serious adverse events. Less than 1 percent of study participants had at least three serious adverse events during the study period.

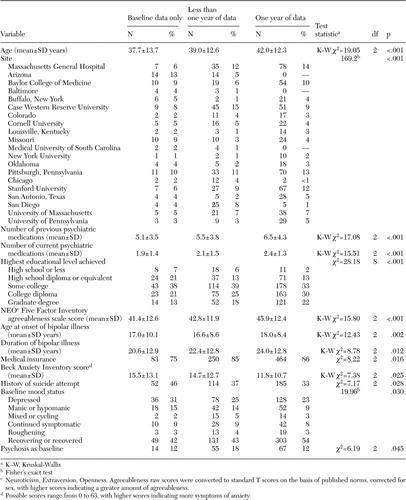

The demographic and diagnostic characteristics of this cohort have been described in detail elsewhere (18). The variables that evidenced significant differences when we compared baseline demographic and clinical characteristics across subgroups of patients who had one year of data, those who had less than one year of data, and those who had baseline data only are shown in Table 2. Data collection procedures for 4.5 percent of the participants did not meet the project's quality assurance standards. Comorbidity data from these patients were excluded from analyses of comparisons of baseline demographic and clinical characteristics across patient subgroups and from bivariate analyses of the occurrence of a serious adverse event with each individual variable. In addition, all data from these patients were excluded from the final best predictive logistic regression models.

Compared with the other two patient subgroups, the subgroup of participants who did not return for follow-up after their initial baseline visit (those in the "baseline data only" subgroup) was younger, less educated, less frequently covered by medical insurance, and more likely to report greater levels of anxiety and a longer history of suicide attempts. These individuals were also taking fewer psychiatric medications at baseline, had fewer previous psychiatric medication trials, and had a shorter duration of bipolar illness. In addition, a greater percentage of these participants entered the study in a depressive, manic, or hypomanic state. Other variables examined did not differ significantly across groups.

Some of the variables had expanded value categories, including total household income (less than $10,000, $10,000 to $19,999, $20,000 to $29,999, $30,000 to $39,999, $40,000 to $49,999, $50,000 to $74,999, $75,000 to $99,999, $100,000 to $149,999, $150,000 to $199,999, and $200,000 or more), marital status (widowed, married, living as married, separated, divorced, and never married), lifetime number of depressive episodes (none, one, two, three or four, five to nine, ten to 20, 20 to 50, too many to count, and indeterminate), and lifetime number of manic or hypomanic episodes (none, one, two, three or four, five to nine, ten to 20, 20 to 50, too many to count, and indeterminate). These categories were collapsed after the baseline comparisons across participant subgroups, and these collapsed categories were used for subsequent bivariate analyses.

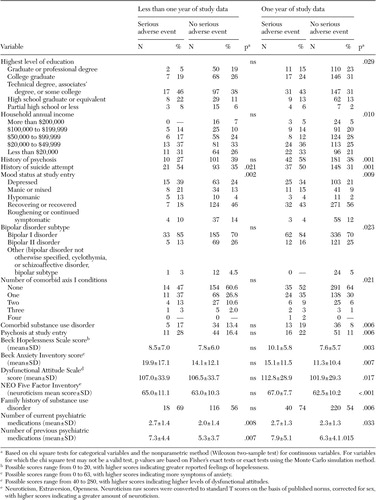

Significant predictor variables based on the bivariate analyses of the occurrence of serious adverse events with each individual variable among patients with one year of prospective data and patients with less than one year of prospective data examined are shown in Table 3.

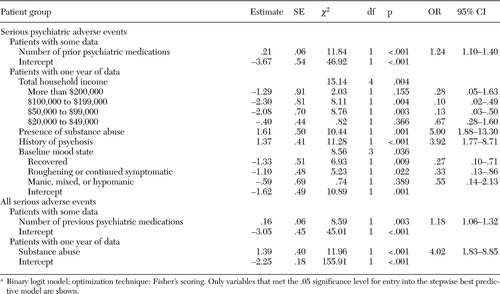

The independent variables were entered into the best predictive stepwise logistic regression models. Variables that were not included in the predictive models because they had a missing data rate of more than 10 percent include Beck Hopelessness Scale score, Beck Anxiety Inventory score, Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale score, NEO Five Factor Inventory subscale scores, and family history of other mood disorder, alcohol or substance use disorders, and suicide attempt or completion. Variables that were significantly predictive of a subsequent serious adverse event on the basis of these models are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

Bipolar spectrum disorders are common and tend to follow a lifelong, highly recurrent course. In addition, they are associated with substantial morbidity, disability, and mortality, including suicide attempt and completion rates that are at least comparable to those reported for patients with major depression. The clinical importance of suicidality is underscored by the fact that hospitalization for suicidal ideation accounted for more than one-quarter of all serious adverse events reported in this cohort.

Despite methodologic limitations, the identification of clinical or demographic factors at initial presentation that may be predictive of subsequent poor outcomes is clinically meaningful. In this study, several such predictors were identified, including concomitant substance abuse, a history of psychosis, a history of numerous previous psychiatric medication trials, low income, and the presence of a fully syndromal major mood episode at study entry.

The presence of a concomitant substance use disorder was highly predictive of a subsequent serious adverse event. This finding is particularly alarming given that substance use disorders are among the most common comorbid axis I diagnoses associated with bipolar disorder. Our findings are consistent with previous reports of the negative impact of comorbid substance use problems (13) among persons with chronic mental illness and underscore the need for identifying and aggressively managing comorbid substance use disorders among patients with bipolar disorder.

Interestingly, a history of psychosis within one year of study entry was also predictive of a subsequent adverse event, whereas the presence of psychosis at study entry was not. Baseline differences in the presence of psychosis across patient subgroups do not appear to account for this finding, because patients who dropped out of the study after enrollment without any additional study follow-up had a lower rate of psychosis at study enrollment compared with subgroups of participants who continued to participate in the study for at least some follow-up after enrollment. These data support the notion that persons with a history of psychosis during a major mood episode have a more severe variant of the illness than those who never become psychotic but that a new episode of psychosis is associated with even higher morbidity, suggesting the need for more aggressive treatment interventions and greater vigilance in monitoring these patients. The fact that acute psychosis did not predict the occurrence of subsequent serious adverse events in this cohort of patients should not be interpreted as suggesting that these individuals do not require aggressive treatment interventions and close clinical monitoring. In this study, we looked at variables associated with long-term—but not immediate—adverse events. Indeed, acute psychosis should alert clinicians to the potential for imminent danger and poor outcomes.

Similarly, a greater number of previous—but not current—psychiatric medication trials was predictive of the occurrence of a serious adverse event. A greater number of previous medication trials, suggesting lack of tolerability, compliance, or response, may also be a proxy for greater severity of illness and treatment resistance. The fact that the number of current psychiatric medications was not associated with adverse events is not surprising, because this variable reflects a cross-sectional view of each patient at a single point in time (study entry).

Low income was also found to be significantly associated with the occurrence of a serious adverse event and has been associated with poor outcomes among patients with chronic mental illness (11). Many factors could account for this finding, such as poor access to health care and severe psychosocial stressors due to financial problems—for example, inadequate or dangerous housing or poor social support. This finding is particularly interesting in the context of this study, because all study participants, in general, had similar access to study physicians and other research clinicians and staff to receive care. This finding suggests that additional resources may be needed to adequately treat and monitor this high-risk population.

Other interesting findings arose when baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who did not return for follow-up after study entry were compared with those of the subgroups of patients who remained in the study. In general, participants who dropped out after study entry without returning for any follow-up care were less educated than those in the other subgroups and reported greater anxiety as well as previous suicide attempts. They were also more likely to have a shorter duration of bipolar illness, fewer previous psychiatric medication trials, and fewer current psychiatric medications and to enter the study during an acute mood episode. Although prospective data for these patients are unavailable, the findings noted above further suggest that patients with acute illness may be at risk and that additional services may be indicated to improve continuity of care.

Contrary to our initial expectations, a number of important clinical and demographic findings were surprisingly not found to be predictive of a serious adverse event in our analyses. For instance, suicidal ideation or attempts accounted for more than 40 percent of psychiatric hospitalizations in this cohort of patients, yet neither suicidal ideation at study entry nor history of suicidality were found to be predictive of the occurrence of a serious adverse event in our best predictive models. However, suicidality was univariately a predictor of serious adverse events in our initial analyses, and suicidality should still alert clinicians to the need for closer clinical monitoring and aggressive treatment.

Methodologically, our analyses examined variables associated with long-term adverse events. Although suicidality at initial presentation did not predict long-term risk of serious adverse events through up to one year of follow-up, suicidality clearly presents an immediate danger that requires careful evaluation and management.

Other variables that, interestingly, were not found to be predictive of a serious adverse event in our analyses were duration of bipolar illness and age at onset. Current knowledge about the natural course of bipolar disorder reflects the fact that this illness tends to be chronic and progressive, with more frequent and severe mood episodes and shorter periods of interepisode recovery occurring over time. However, the duration of bipolar illness was not significantly related to the occurrence of a serious adverse event in our bivariate analyses and best predictive logistic regression models. Furthermore, although early onset of bipolar disorder has been associated with a more severe course of illness in this cohort (19) and with overall poor outcomes elsewhere (20), age at onset in our analyses was not specifically predictive of the occurrence of a serious adverse event during this study. This finding further supports the notion that the acuity of the illness may be a greater risk for serious adverse events among patients with bipolar disorder.

Several limitations of this study merit discussion. First, our analyses were based primarily on identifying variables that were present at study entry that were predictive of the occurrence of a serious adverse event though up to a year of subsequent follow-up. A logical next step in examining predictors of poor outcomes would be to examine predictors of a subsequent serious adverse event within a shorter period, such as factors predictive of a subsequent poor outcome within a month. Also, there were several variables that it was not possible for us to examine in our analyses, including treatment nonadherence, major comorbid medical conditions, a history of previous hospitalizations, life stressors, and major personality disorders. Treatment nonadherence is a major problem in all areas of medicine, including psychiatry, and its impact on clinical outcomes has been reported (12,13,21).

Although our study data did not allow us to examine this issue specifically, it would certainly be an interesting focus in future studies. Similarly, major medical illnesses could negatively affect outcomes among patients with bipolar disorder, and determining specific medical problems that have the largest impact would be important and clinically useful. Furthermore, the best predictive models excluded variables for which there was a high rate of missing data, including measures of anxiety, hopelessness, dysfunctional attitudes, and personality domains, each of which could conceivably have a significant impact on clinical outcomes.

Finally, a notable limitation of this study was the use of serious adverse events to describe clinical outcomes. Although some adverse events, such as hospitalization for a worsening mood state, may be seen as an expected outcome in the course of bipolar disorder, the occurrence of such an event also reflects a poor outcome during the course of clinical care. Thus identifying predictors of serious adverse events, although an a priori limited and defined concept, still provides practicing clinicians with meaningful data about factors that warrant close clinical attention as they care for patients with bipolar disorder.

Conclusions

This study identified several baseline factors that may be predictive of an impending poor outcome among patients with bipolar disorder, including the presence of substance abuse, low income, a syndromal mood episode, a history of psychosis, and a greater number of previous psychiatric medications. The acuity of the illness in a patient with bipolar disorder at initial presentation is particularly worrisome and should alert clinicians to the need for aggressive treatment and close clinical monitoring to prevent poor outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), under contract N01-MH-80001. This article was approved by the publication committee of the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Details of past and current STEP-BD participants can be found at www.stepbd.org/research/stepacknowledgmentlist.pdf.

Dr. Martinez and Dr. Marangell are affiliated with the Mood Disorders Center, Menninger Department of Psychiatry, Baylor College of Medicine, Ben Taub Hospital, 6655 Travis Street, Suite 560, Houston, Texas 77030 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Simon and Dr. Pollack are with the Center for Anxiety and Traumatic Stress Disorders at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Ms. Miyahara and Dr. Wisniewski are with the Epidemiological Data Center of the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh. At the time of this study, Ms. Harrington was affiliated with Massachusetts General Hospital. Dr. Sachs is with the Partners Bipolar Disorder Treatment Center of Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School. Dr. Thase is with the department of psychiatry of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

|

Table 1. Description and frequency of serious adverse events (N=161) reported in a sample of 1,000 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) through up to one year of study participation

|

Table 2. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD), according to completeness of follow-up data through one year of study participation

|

Table 3. Significant predictor variables based on bivariate analysis of the occurrence of a serious adverse event, according to completeness of follow-up data through up to one year of participation in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD)

|

Table 4. Variables significantly associated with subsequent occurrence of a serious adverse event among patients in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) according to the best predictive modela

a Binary logit model; optimization technique: Fishers scoring. Only variables that met the .05 significance level for entry into the stepwise best predictive model are shown.

1. Cohen HW, Madhavan S, Alderman MH: History of treatment for depression: risk factor for myocardial infarction in hypertensive patients. Psychosomatic Medicine 63:203–209,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Von Ammon, Cavanaugh S, Furlanetto LM, et al: Medical illness, past depression, and present depression: a predictive triad for in-hospital mortality. American Journal of Psychiatry 158:43–48,2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Holmes J, House A: Psychiatric illness predicts poor outcomes after surgery from hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. Psychological Medicine 30:921–929,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Huang BY, Cornoni-Huntley J, Hays JC, et al: Impact of depressive symptoms on hospitalization risk in community-dwelling older patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 48:1279–1284,2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Shiotani I, Sato H, Kinjo K, et al: Depressive symptoms predict 12-month prognosis in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Cardiovascular Risk 9:153–160,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lopes AA, Bragg J, Young E, et al: Depression as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization among hemodialysis patients in the United States and Europe. Kidney International 62:199–207,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Almagro P, Calbo E, Ochoa de Echaguen A, et al: Mortality after hospitalization for COPD. Chest 121:1441–1448,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bula CJ, Wietlisbach V, Burnand B, et al: Depressive symptoms as a predictor of 6-month outcomes and services utilization in elderly medical inpatients. Archives of Internal Medicine 161:2609–2615,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Connerney I, Shapiro PA, McLaughlin JS, et al: Relation between depression after coronary artery bypass surgery and 12-month outcome: a prospective study. Lancet 358:1766–1771,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Jiang W, Alexander J, Christopher E, et al: Relationship of depression to increased risk of mortality and rehospitalization in patients with congestive heart failure. Archives of Internal Medicine 161:1849–1856,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Polk-Walker GC, Chan W, Meltzer AA, et al: Psychiatric recidivism prediction factors. Western Journal of Nursing Research 15:163–176,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Green JH: Frequent rehospitalization and noncompliance with treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:963–966,1988Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Haywood TW, Kravitz HM, Grossman LS, et al: Predicting the "revolving door" phenomenon among patients with schizophrenic, schizoaffective, and affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:856–861,1995Link, Google Scholar

14. Hoffmann H: Age and other factors relevant to the rehospitalization of schizophrenic outpatients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89:205–210,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Swett C: Symptom severity and number of previous psychiatric admissions as predictors of readmission. Psychiatric Services 46:482–485,1995Link, Google Scholar

16. Daniels BA, Kirkby KC, Hay DA, et al: Predictability of rehospitalization over 5 years for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 32:281–286,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Winokur G, Coryell W, Keller M, et al: A prospective follow-up of patients with bipolar and primary unipolar affective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:457–465,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Kogan JN, Otto MW, Bauer MS, et al: Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the first 1,000 patients enrolled in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Bipolar Disorders 6:460–469,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Perlis RH, Miyahara S, Marangell LB, et al: Long-term implications of early onset of bipolar disorder: data from the first 1000 participants in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder (STEP-BD). Biological Psychiatry 55:875–881,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Carter TDC, Mundo E, Parikh SV, et al: Early age at onset as a risk factor for poor outcome of bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 37:297–303,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Tsai S-Y, Chen C-C, Kuo C-J, et al:15–year outcome of treated bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 63:215–220,2001Google Scholar