Use of Health Care Services Among Persons Who Screen Positive for Bipolar Disorder

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined patterns of diagnosis, consultation, and treatment of persons who screened positive for bipolar disorder. METHODS: An impact survey was mailed to a representative subset of 3,059 individuals from a large U.S.-population-based study that utilized the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ). RESULTS: Respondents who screened positive on the MDQ (reported the presence of seven of 13 symptoms of bipolar disorder, the co-occurrence of at least two symptoms, and moderate or severe symptom-related impairment) (N=1,167) had consulted a health care provider more often in the previous year than those who screened negative (reported six or fewer symptoms regardless of symptom co-occurrence or impairment) (N=1,283). Psychiatrists and primary care physicians failed to detect or misdiagnosed bipolar disorder among 53 percent and 78 percent of patients, respectively, who screened positive for bipolar disorder. The most commonly used psychotropic medications during the previous 12 months among those who screened positive were antidepressants alone (32 percent), followed by lithium and anticonvulsant mood stabilizers (20 percent), antidepressants in combination with other psychotropics (19 percent), hypnotics (19 percent), and antipsychotics (9 percent). In the preceding 12 months, respondents who screened positive on the MDQ had greater use of psychiatric hospitals, emergency departments, and urgent care centers and also had more outpatient visits to primary care physicians, psychiatrists, and alcohol treatment centers than those who screened negative. CONCLUSIONS: The results of this study suggest that bipolar disorder is an underdiagnosed and often inappropriately treated illness associated with significant use of health care resources.

Bipolar I disorder is a chronic episodic illness that affects approximately 1 percent of the U.S. population and is associated with substantial morbidity, functional disability, and mortality (1,2,3). A recent population-based screening suggested that the prevalence of bipolar I and II disorder in the United States is 3.4 percent (4). It is increasingly clear that even subsyndromal symptoms have a negative impact on measures of work, social functioning, and quality of life (5,6,7).

In view of its prevalence and associated morbidity and mortality, bipolar disorder is considered to be a major public health problem (8). This disorder presents unique challenges in diagnosis and management, partly because of its variable presentation and patients' delay in seeking—or failure to seek—appropriate medical care. Although bipolar disorder is acknowledged to be underrecognized and undertreated (4,9,10), little is known about how patients with the disorder enter the U.S. health care system and how their illness is diagnosed and managed. Whether through the patient's choice (that is, having an established relationship with a primary care physician), predetermined insurance plan restriction on psychiatric consultation, or clinical expertise, bipolar illness is increasingly being managed by primary care physicians. The population-based study reported here was conducted in 2001 and examined patterns of diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder in the United States by utilizing the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ), a screening instrument for bipolar disorder (11,12,13).

Methods

The study's methods have been fully described elsewhere (4,12). Briefly, the sample was drawn from a nationwide panel of more than 600,000 households representative of the U.S. population in terms of place of residence, age of the head of the household, household income, and household size. Study participants completed the MDQ, a bipolar disorder screening tool that has been validated against a research diagnostic interview in a clinical psychiatric outpatient sample (73 percent sensitivity and 90 percent specificity) and in a nonclinical, U.S.-population-based sample (28 percent sensitivity and 97 percent specificity) (12,13).

The survey was mailed in January 2001 to 127,800 persons who were at least 18 years of age. Evaluable surveys were returned by 85,358 respondents (66.8 percent). Respondents were considered to have screened positive for bipolar disorder (that is, to screen positive on the MDQ) if they reported the presence of seven of 13 symptoms of bipolar disorder, the co-occurrence of at least two symptoms, and moderate or severe symptom-related impairment. Respondents were considered to have screened negative on the MDQ if they reported six or fewer bipolar symptoms, regardless of symptom co-occurrence, or symptom impairment ratings of at least seven symptoms of bipolar disorder without co-occurrence and impairment. The overall rate of positive screening for bipolar I and II disorder, weighted to match U.S. census demographic data, was 3.4 percent (4).

Subgroups of respondents to the initial prevalence survey who screened positive on the MDQ (N=1,529) and those who screened negative (N=1,530) were randomly assigned to receive a subsequent impact survey some time between March and June 2001. The survey contained questions assessing medication use and health care consulting patterns in the previous 12 months. These subgroups were balanced to match the data set from the first prevalence survey on key demographic variables, including age, gender, geographic region, population density, household income, and household size.

End points of interest for this analysis included the first and most frequently consulted medical specialty, clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder as a function of the health care provider's medical specialty, use of various categories of psychotropic medications (mood stabilizers [lithium and anticonvulsants], antipsychotics, antidepressants, and alternative remedies [herbal remedies, vitamins, and other nonprescription treatments]) in the preceding 12 months, use of health care resources (general or psychiatric hospitalization, emergency department or urgent care evaluation, or outpatient visits) in the preceding 12 months, and use of social services (alcohol treatment center, drug treatment center, and detox facility days) in the preceding 12 months.

The returned surveys were postweighted to match the original sample on key demographic variables. All percentages reported here are weighted unless otherwise indicated. Statistical analyses were performed with use of the WesVar statistical software package (Westat, Rockville, Maryland), which is designed to accommodate complex probability samples and weighted survey data. Chi square tests were used to analyze discrete variables, and t tests were used to compare means for respondents who screened positive and those who screened negative when appropriate.

Results

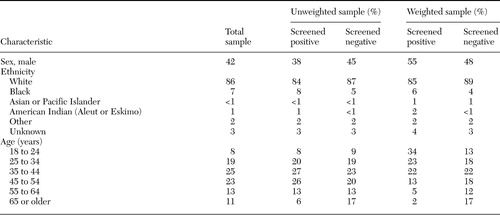

Surveys were returned by a total of 2,450 respondents (1,167 who screened positive on the MDQ, for a return rate of 76.3 percent, and 1,283 who screened negative, for a return rate of 83.9 percent), for an overall return rate of 80.1 percent. Table 1 presents unweighted and weighted demographic data for respondents who screened positive and those who screened negative. After postweighting, the gender breakdown of the sample was approximately half female (52 percent). The respondents' mean age was 45.4 years.

Consulting patterns

Significantly more respondents who screened positive than those who screened negative reported having ever consulted a health care provider for bipolar symptoms (53.7 percent compared with 26.2 percent; χ2=46.95, df=1, p<.001). For respondents who screened positive and who had consulted a health care provider (620 respondents), primary care physicians were consulted most often (40.5 percent), followed by psychiatrists (25.9 percent), psychologists or counselors (26.0 percent), other M.D.s (4.6 percent), and other non-M.D.s (3.0 percent).

Diagnosis patterns among respondents who screened positive

Fewer than one in five respondents (17.7 percent) who screened positive on the MDQ reported receiving a clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder; 41.6 percent received a misdiagnosis of something other than bipolar disorder, and 40.7 percent did not receive a diagnosis. Among respondents with bipolar disorder who were given a misdiagnosis, 63.2 percent were given a diagnosis of unipolar depression; 17.8 percent, unipolar depression and substance use disorder; and 19.0 percent, substance use disorder alone. Among the three main types of mental health care providers, psychiatrists were most likely to diagnose bipolar disorder among respondents who screened positive (47.3 percent). However, psychiatrists misdiagnosed or did not detect bipolar disorder for more than half the patients who screened positive on the MDQ (52.7 percent); this was true for primary care physicians 78.0 percent of the time and for psychologists or counselors 77.5 percent of the time (χ2=15.07, df=2, p=.001).

Psychotropic medication use by respondents who screened positive

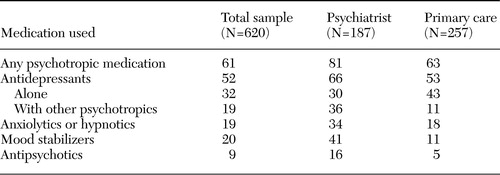

Table 2 summarizes psychotropic medication use for respondents who were seen most often by a psychiatrist or a primary care physician. The most commonly used psychotropic medications among respondents who screened positive for bipolar disorder on the MDQ were antidepressant monotherapy (32.3 percent), followed by mood stabilizers (20 percent), antidepressants and other psychotropics (19.3 percent), anxiolytics and hypnotics (19.2 percent), and antipsychotics (9 percent). Psychiatrists were more likely than primary care physicians to prescribe mood stabilizers for respondents who screened positive (41.4 percent compared with 11.3 percent; χ2=29.24, df=1, p<.001). Conversely, primary care physicians were more likely to prescribe antidepressants (without mood stabilizers or antipsychotics) than psychiatrists (42.9 percent compared with 29.8 percent; χ2=3.56, df=1, p=.059).

Among the subset of respondents who screened positive for bipolar disorder on the MDQ and who were also given a correct diagnosis, only 38.7 percent overall were given a prescription for a mood stabilizer, and 26.8 percent received an antidepressant alone (without a mood stabilizer or an antipsychotic). Similarly, psychiatrists were more likely than primary care physicians to prescribe a mood stabilizer (56.9 percent compared with 24.6; χ2=7.93, df=1, p<.005); conversely, primary care physicians were more likely than psychiatrists to prescribe antidepressants (without mood stabilizers or antipsychotics) (37.2 percent compared with 20.9 percent), but this effect was noted only as a trend (p<.08).

Use of health care resources

Patterns of use of health care resources in the previous 12 months indicated that respondents who screened positive on the MDQ used more health care resources than did those who screened negative, as evidenced by the mean number of days (and 95 percent confidence interval) in a psychiatric hospital (.42±.35 compared with .01±.02, p=.022), emergency department visits (.29±.13 compared with .04±.04, p<.001), urgent care visits (.05±.03 compared with .01±.01, p=.024), visits to a primary care physician (1.38±.47 compared with .45±.31, p=.002), visits to a psychiatrist (1.21±.43 compared with .16±.10, p<.001), and visits to a psychologist (2.43±.79 compared with .51±.42, p<.001).

Respondents who screened positive for bipolar disorder on the MDQ also used more social service resources in the previous 12 months than those who screened negative, as evidenced by the mean number of total social service days (2.52±2.06 compared with .25±.39, p<.036). Use of various types of social service treatment centers varied between respondents who screened positive and those who screened negative, as evidenced by the mean number of detoxification facility days (.02±.01 compared with 0, p=.04), alcohol treatment center days (.54±.53 compared with 0, p=.044), and drug treatment center days (.25±.35 compared with .18±.37, not significant).

Discussion

The results of this U.S.-population-based study suggest that bipolar disorder is frequently undetected or misdiagnosed, even among patients who consult psychiatrists. Overall, only one in five respondents who screened positive on the MDQ for bipolar disorder reported receiving a physician's diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Psychiatrists were more likely than primary care physicians and psychologists or counselors to diagnose bipolar disorder among persons who screened positive on the MDQ. However, psychiatrists diagnosed bipolar disorder only among approximately 50 percent of respondents who had screened positive for the disorder. That fewer than one in four respondents who screened positive and who consulted a primary care physician received a diagnosis of bipolar disorder is alarming given that a primary care physician had been the main provider of health care during the year before the survey for a sizable minority of respondents who screened positive on the MDQ (41 percent).

It has been suggested that recognition of bipolar depression can be difficult because of patients' tendency to underreport hypomania or mania, the overlap of symptoms between bipolar and unipolar depression, and the presence of comorbid conditions (14). This study highlights the fact that the most common misdiagnosis among respondents who screen positive on the MDQ is unipolar depression.

Similar results have been obtained in other clinic- and community-based studies (15,16,17,18,19). For example, in a study of 48 consecutive patients who were referred to a psychiatric clinic and given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, 40 percent were found to have previously undiagnosed bipolar disorder; all had previously been given a diagnosis of unipolar major depressive disorder (15). Similarly, in a 2000 survey of 600 members of the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association with a self-reported diagnosis of bipolar disorder, 69 percent of respondents were given a misdiagnosis, most often unipolar depression (19); these individuals consulted a mean of four physicians before receiving a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The lag between the initial consultation for symptoms and receipt of an accurate diagnosis was at least ten years for approximately one-third of respondents.

Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder as unipolar depression is not surprising given that affected individuals may be more likely to consult a physician while experiencing depressive symptoms than while experiencing hypomania or mania. This consideration underscores the importance of taking a careful history to assess for manic or hypomanic symptoms experienced by any patient who is evaluated while apparently depressed.

Misdiagnosis of bipolar disorder as unipolar depression can be deleterious, because the cornerstone treatments (mood stabilizers for bipolar disorder and antidepressants for unipolar depression) are different. Experts discourage the use of antidepressant monotherapy for bipolar disorder, because antidepressants have the potential to induce mania or hypomania and to cause or exacerbate rapid cycling (20,21,22). Mood stabilizers (lithium, divalproex sodium, lamotrigine, and olanzapine) are the standard of care for bipolar disorder and are recommended by American Psychiatric Association practice guidelines for acute and maintenance treatment (20).

In the study reported here, antidepressants were prescribed three times as often as mood stabilizers for respondents who screened positive for bipolar disorder on the MDQ. These data suggest that mood stabilizers were underused, whereas antidepressants were overused in the management of bipolar disorder in this U.S.-population-based sample. This problem was particularly marked for respondents who consulted primary care physicians. Respondents who screened positive and who consulted primary care physicians were approximately twice as likely to report use of antidepressants (without mood stabilizers or antipsychotics) as were those who consulted psychiatrists. This finding has real-world implications: a recent study highlighted the fact that patients with unrecognized bipolar disorder (antidepressant-induced mania) incur greater mean monthly medical costs in the 12 months after initiation of antidepressant treatment than do established patients with bipolar disorder or unipolar depression (23).

The underuse of mood stabilizers among these patients with bipolar disorder is particularly worrisome in the context of the recent finding that delayed initiation of treatment with mood stabilizers increases bipolar disorder-associated morbidity and mortality. In a study of 56 patients with bipolar disorder, the mean lag time from the initial appearance of mood symptoms to initiation of treatment with a mood stabilizer was ten years (24). The longer the delay between symptom onset and initiation of treatment with a mood stabilizer, the greater the number of annual hospitalizations and the greater the likelihood of at least one suicide attempt. These relationships were observed regardless of whether the index episode was depressive or manic.

The findings of this study should be considered in the context of its limitations. Unequivocally, a limitation of the study is that the MDQ is a screening instrument for bipolar disorder and not a diagnostic instrument. However, the MDQ has been found to have generally good sensitivity and specificity in terms of research diagnostic interviews obtained from trained interviewers within both clinical samples (73 percent sensitivity and 90 percent specificity) and nonclinical population-based samples (28.1 percent sensitivity and 97.2 percent specificity) (12,13). The relatively lower rates in the general population limit the interpretations of these findings. Therefore, it is possible that the misdiagnosis rates by all the mental health care providers are incorrect given that we relied on patients' self-report.

Conclusions

The results of this U.S.-population-based study indicate that bipolar disorder is an underdiagnosed and often inappropriately treated illness. Underdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment of bipolar disorder were particularly common in the primary care setting but were also alarmingly high among psychiatrists, who did not detect bipolar disorder among approximately half of respondents who screened positive for the disorder on the MDQ. Improvement in diagnosis of bipolar disorder and increased use of mood stabilizers are imperative in reducing morbidity and mortality associated with bipolar disorder. Given that many patients with bipolar disorder have already established a relationship with a primary care physician, particular attention should be paid to the role of primary care in the diagnosis and optimal treatment of bipolar disorder.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Kristina Fanning, Ph.D., for providing valuable statistical analyses and Angela Devaugh-Geiss, M.S., for providing valuable consultation.

Dr. Frye is affiliated with the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences of the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, 300 UCLA Medical Plaza, Suite 1544, Los Angeles, California 90095 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Calabrese is with the department of psychiatry of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Dr. Reed is with Vedanta Research in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Dr. Wagner and Dr. Hirschfeld are with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the University of Texas at Galveston. Ms. Lewis is with the Depression and Bipolar Support Alliance in Chicago. Mr. McNulty is with the National Alliance on Mental Illness in Alexandria, Virginia.

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of survey respondents who screened positive for bipolar disorder (N=1,167) and those who screened negative (N=1,283) according to the Mood Disorder Questionnaire

|

Table 2. Percentage use of psychotropic medications over the previous 12 months among survey respondents who screened positive for bipolar disorder on the Mood Disorder Questionnaire, by type of health care provider seen most often

1. Weissman MM, Bland RC, Canino GJ, et al: Cross-national epidemiology of major depression and bipolar disorder. JAMA 276:293–299,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Weissman MM, Bruce ML, Leaf PJ, et al: Affective disorders, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiological Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8–19,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hirschfeld RM, Calabrese JR, Weissman MM, et al: Screening for bipolar disorder in the community. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:53–59,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Robb JC, Cooke RG, Devins GM, et al: Quality of life and lifestyle disruption in euthymic bipolar disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 31:509–517,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, et al: Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1635–1640,1995Link, Google Scholar

7. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al: The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 59:530–537,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Murray CJ, Lopez AD: Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 349:1436–1442,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Arnold LM: Bipolar disorder. Medical Clinics of North America 85:645–661,2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Grochocinski VJ, et al: Demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals in a bipolar disorder case registry. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:120–125,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Calabrese JR, Hirschfeld RM, Reed M, et al: Impact of bipolar disorder on a US community sample. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:425–432,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al: Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1873–1875,2000Link, Google Scholar

13. Hirschfeld RM, Holzer C, Calabrese JR, et al: Validity of the mood disorder questionnaire: a general population study. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:178–180,2003Link, Google Scholar

14. Bowden CL: Strategies to reduce misdiagnosis of bipolar depression. Psychiatric Services 52:51–55,2001Link, Google Scholar

15. Ghaemi SN, Sachs GS, Chiou AM, et al: Is bipolar disorder still underdiagnosed? Are antidepressants overutilized? Journal of Affective Disorders 52:135–144,1999Google Scholar

16. Hantouche EG, Akiskal HS, Lancrenon S, et al: Systematic clinical methodology for validating bipolar-II disorder: data in mid-stream from a French national multi-site study (EPIDEP). Journal of Affective Disorders 50:163–173,1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Akiskal HS, Maser JD, Zeller PJ, et al: Switching from 'unipolar' to bipolar II: an 11-year prospective study of clinical and temperamental predictors in 559 patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:114–123,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR: Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity, and course. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:454–463,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Hirschfeld RM, Lewis L, Vornik LA: Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the national depressive and manic-depressive association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:161–174,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1–50,2002Link, Google Scholar

21. Calabrese JR, Rapport DJ, Kimmel SE, et al: Controlled trials in bipolar I depression: focus on switch rates and efficacy. European Neuropsychopharmacology 9(suppl 4):S109–112, 1999Google Scholar

22. Wehr TA, Sack DA, Rosenthal NE, et al: Rapid cycling affective disorder: contributing factors and treatment responses in 51 patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:179–184,1988Link, Google Scholar

23. Birnbaum HG, Shi L, Dial E, et al: Economic consequences of not recognizing bipolar disorder patients: a cross-sectional descriptive analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:1201–1209,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Goldberg JF, Ernst CL: Features associated with the delayed initiation of mood stabilizers at illness onset in bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:985–991,2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar