Rehab Rounds: Drug and Psychosocial Curricula for Psychiatry Residents for Treatment of Schizophrenia: Part II

Abstract

Introduction by the column editor: In most scientific fields and medical specialties, competency-based training is old hat. Before doctoral candidates can earn their Ph.D., they must produce a research thesis that requires designing a study, recruiting participants, administering tests, delivering an intervention with fidelity, collecting data, reporting results, and defending the thesis. Before they complete a residency in surgery or internal medicine, trainees must be able to conduct patient examinations, make valid diagnoses, and perform procedures with acceptable techniques and outcomes. This month's column proposes recommendations for criterion-referenced methods for ascertaining the skills acquired by psychiatric residents in the psychosocial treatment of persons with schizophrenia.

In all medical specialties, determination of competency is based on behavioral criteria that are scrutinized and evaluated through direct observation of evidence-based methods. Psychiatry residents can graduate and enter practice with minimal direct observation of their behavioral competencies by faculty members who, in any event, lack operational criteria for evaluating use of evidence-based diagnostic and treatment techniques (1). One of the reasons for the disparity between psychiatry and other medical specialties derives from a lack of standardized and reliable measurement of processes and outcomes in conducting assessments and treating patients in clinical settings (2).

However, there is a movement to bring psychiatry residency training into line with the rest of medicine. For example, the residency review committee for psychiatry of the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education now requires that all psychiatry residency programs demonstrate that their residents have attained competency for all evidence-based psychotherapeutic treatments (3). However, such competencies have not yet been operationalized nor consensually identified.

The November 2004 column proposed a curriculum on the pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia for psychiatry residents that is based on empirically validated research, treatment guidelines, and algorithms (4). This month's column proposes a competency-based curriculum on the psychosocial treatment of persons with serious and persistent mental disorders.

"Competencies" refers to the attitudes, knowledge, and skills psychiatrists must possess to deliver high-quality care (5). Two national consensus panels, sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services and the Center for Health Care Strategies, identified 11 core competencies for the effective treatment and rehabilitation of persons with serious mental illness: developing a therapeutic relationship; conducting reliable symptom assessments and diagnostic evaluations; medical evaluation and treatment; functional assessment; empowering the individual; integrating psychopharmacology and psychosocial treatments; social skills training; family education and encouragement of family involvement in treatment; transitional and supported employment; clinical case management; and consumer self-help and advocacy.

Each of these competencies can be further subdivided into criterion-based components. For example, performing an adequate functional assessment includes identifying and specifying personally meaningful goals; identifying stressors and reinforcers linked to illness; identifying basic needs for financial support, food, shelter, and safety; specifying measurable goal attainment; specifying behavioral, attitudinal, knowledge-based, and cognitive strengths, interests, and deficits relevant to goal attainment, including cultural factors that can be used to support recovery; identifying attitudes, behaviors, cognitions, and environmental supports that influence adherence to medication and other treatments; conducting a motivational analysis of reinforcers for promoting adaptive behavior; and delineating community, social, and tangible resources and supports available for treatment and rehabilitation. Each competency was delineated with measurable criteria that can be adapted for curricula in residency training. Thus selective competencies can be considered for criterion-based training of psychiatry residents and allied mental health professionals. Manuals describing the competencies can be obtained from the author.

Therapeutic relationship and alliance

Among the competencies necessary to treat persons with serious mental illness are engagement, collaboration, education, and empowerment of the client. Given the passivity, negative symptoms, and impaired cognitive functions of most individuals with schizophrenia, mental health practitioners must give high priority to acquiring the attitudes, knowledge, and skills necessary to establish and maintain effective communication, reciprocal and appropriate self-disclosure, and a mutually respectful partnership in treatment. These competencies are important for ensuring clients' attendance at evaluations and medication management and psychosocial treatment sessions as well as adherence to treatment (6).

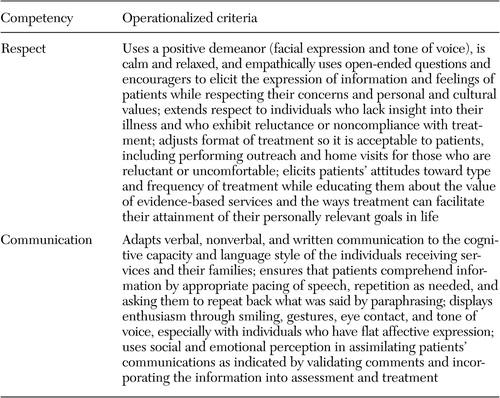

For generations, the therapeutic alliance has been identified as the sine qua non of all forms of effective psychiatric care (7). The attitudes, knowledge, and skills required to develop and maintain the alliance include empathy, warmth, genuine concern, an ability to listen, access to the therapist, realistic optimism, and destigmatization. The components of the therapeutic alliance have been operationalized into measurable skills (8), but they have not been systematically and objectively assessed among psychiatry residents. Two of these competencies are shown in Table 1. Competency-based techniques could be taught to residents whose acquisition of relationship skills could then be observed and evaluated by faculty in appropriate clinical settings. The learning of specific relationship competencies by residents would be promoted by including them in graduation criteria from training programs, quality improvement reviews, and board-certifying organizations.

Social skills training

An important competency for psychiatry residents to acquire is the ability to conduct social skills training. Most individuals with schizophrenia have never developed social and independent living skills, because their disorders preceded and interfered with such learning. In addition, schizophrenia is associated with widespread cognitive deficits in areas that are instrumental in learning and using social skills.

Residents are taught the importance of neurophysiology and other neurosciences for the informed use of pharmacologic agents but do not receive any training in behavioral learning principles and techniques that are the basis for social skills training and other cognitive-behavioral therapies. Skills training methods make use of all the basic mechanisms of human learning, because persons with schizophrenia have considerable learning disabilities that require highly structured, systematic, repetitious, and active teaching techniques.

Functioning as an active special education teacher is awkward and unfamiliar for mental health professionals who are trained to use more traditional methods that are aimed at reducing, stabilizing, or eliminating symptoms. Social skills training requires quite different competencies—namely, the ability to identify an individual's real-life goals and use stepwise interventions to facilitate the acquisition and use of needed skills.

The specific competencies inherent in the effective provision of social skills training are listed in the box on the next page as behavioral interactions with patients that reflect fidelity to the skills training enterprise. If the psychiatric practitioner faithfully adheres to the specific techniques for any procedure associated with positive outcomes in research, the clinical results are also likely to be positive (9). Fidelity scales and operationalized manuals are now available for many evidence-based psychosocial services, including assertive community treatment, family psychoeducation and behavioral family therapy, and the individual placement and support mode of supported employment.

During the past 25 years in the department of psychiatry of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), psychiatry residents and other mental health professionals have taken elective rotations to become competent in conducting social skills training for persons with schizophrenia (10). Competency has been acquired through two curricula: an apprenticeship wherein the resident serves as co-trainer with an expert faculty member in a social skills training group, and the use of highly structured trainers' manuals to teach patients social and independent skills in the UCLA module series (11). In both curricula, competency-based checklists are used to give feedback to trainees as they gain facility in conducting social skills training.

It is perhaps not surprising that the use of social skills training by psychiatrists and other mental health professionals has become much more prevalent in Japan than in the United States (12). The Japanese Association for Social Skills Training was founded by psychiatrists who successfully advocated to have the Japanese Ministry of Health reimburse social skills training as a bona fide treatment modality. Although psychiatrists are not the only disciplinary group that can effectively deliver social skills training, unless they learn to use the methods effectively and can teach and supervise others, they will continue to lose their credibility as team and program leaders of services for persons with serious and persistent mental disorders.

Practitioner competencies for effective use of social skills training

• Actively helps the patient to set specific, personally relevant long- and short-term goals

• Promotes realistically favorable expectations by using motivational interviewing

• Helps the patient create an interpersonal situation that may occur during the next week and, if managed successfully, would bring the patient closer to reaching his or her longer-term goal

• Builds a scene that replicates the situation by asking the patient, What emotion or communication do you want to convey? To whom? Where? And when?

• Structures a role play by setting a scene with roles for the patient and surrogates and encourages behavioral rehearsal and using self or other patients as role models for demonstrating skills to the patient before the patient engages in the role play (social learning)

• Gives the patient positive and corrective feedback for verbal and nonverbal behaviors, reciprocity in conversation, and accurate social perception

• Actively coaches the patient while the patient engages in behavioral rehearsal of the scene with prompting, encouraging and reinforcing appropriate verbal and nonverbal behaviors

• Shapes improvements in behavioral skills in small, attainable increments

• Gives specific and attainable and functional homework assignments to practice in real-life situations that were practiced in the training session

• Solicits reports on homework assignments and, depending on success in attaining the short-term goal, moves on to a new goal, repeats practicing of the former goal, or engages in problem-solving to remove obstacles to successful use of the skills in everyday life

Conclusions

The operationalization of evidence-based biobehavioral treatments can be useful in residency training and continuing education in psychiatry. The aphorism used in accreditation of hospitals—"If it isn't in the medical record, it hasn't occurred"—has its parallel in the implementation of evidence-based treatments: If you can't see the skills being used with fidelity by the trainee, the educational process has failed. The need for translating effective treatments from research to practice is underlined by findings from surveys of practicing psychiatrists. The American Psychiatric Association's practice research network found glaring discrepancies between what psychiatrists know about optimal treatment of schizophrenia and what they implement in practice (13).

Afterword by the column editor: Inserting criterion-referenced, competency-based training into the educational process may be necessary but not sufficient for accelerating the pace at which practitioners adopt evidence-based treatments. When third-party payers make reimbursement contingent on documented use of evidence-based treatments, more effective treatments will be implemented. Such contingencies are beginning to occur, as witnessed by an unprecedented law adopted by the Oregon legislature in 2003 that will require behavioral health providers to demonstrate that at least 25 percent of services have scientific support (14).

Dr. Liberman, who is editor of this column, is professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, Neuropsychiatric Institute, 760 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, California 90095 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Competencies for developing and sustaining the therapeutic alliance

1. Sudak DM, Beck JS, Gracely EJ: Readiness of psychiatry residency training programs to meet the ACGME requirements in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Academic Psychiatry 26:96–101, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Yager J, Bienenfeld D: How competent are we to assess psychotherapeutic competence in psychiatric residents? Academic Psychiatry 27:174–181, 2003Google Scholar

3. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education: Program Requirements for Residency Training in Psychiatry, 2000. Available at www.acgme.org/rrc/psy-req.aspGoogle Scholar

4. Liberman RP, Glick I: Drug and psychosocial curricula for psychiatric residents for treatment of schizophrenia: part I. Psychiatric Services 55:1217–1219, 2004Link, Google Scholar

5. Coursey RD: Competencies for Direct Services Staff Who Work With Adults With Serious Mental Illnesses in Public Mental Health Programs, 3rd rev. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1998Google Scholar

6. Frank AF, Gunderson JG: The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of schizophrenia: relationship to course and outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:228–237, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Horvath A, Luborsky L: The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61:561–573, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Summers RF, Barber JP: Therapeutic alliance as a measurable psychotherapy skill. Academic Psychiatry 27:160–165, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Skills training vs psychosocial occupational therapy for persons with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1087–1091, 1998Link, Google Scholar

10. Hierholzer RW, Liberman RP: Successful living: a social skills and problem solving group for the chronic mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:913–918, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

11. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Innovations in skills training for the serious mentally ill: the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills modules. Innovations and Research 2:43–60, 1993Google Scholar

12. Ikebuchi E, Anzai N, Niwa SI: Adoption and dissemination of social skills training in Japan. International Review of Psychiatry 10:71–75, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Psychiatrists' use of treatment guidelines for schizophrenia. Psychiatric Research Report 20(4):6–7, 2004. Available at www.psych.org/research/dor/prr/index.cfmGoogle Scholar

14. Evidence Based Practice Act (Senate Bill 267), 72nd Oregon Legislative Assembly-2003 Regular Session, Section 5Google Scholar