Psychiatrists' Attitudes Toward Involuntary Hospitalization

Abstract

This study examined whether psychiatrists' attributions of responsibility for mental illnesses affect their decisions about involuntary hospitalization. A survey that was mailed in 2002 to members of the Illinois Psychiatric Society elicited recommendations for involuntary commitment for vignette characters. The survey also sought respondents' attributions of personal responsibility for the onset and recurrence of mental illnesses. A total of 432 psychiatrists responded to the survey. Decisions to involuntarily hospitalize persons with mental illness increased significantly with the level of risk of harm and varied significantly between psychiatric diagnoses. Attributions of responsibility were not related to commitment decisions.

All states permit the involuntary hospitalization of persons with mental illness who are expected to inflict serious physical harm on themselves or another in the near future or who are unable to provide for their basic physical needs. In previous investigations dangerousness did, in fact, determine psychiatrists' commitment decisions, as did judgments about clinical treatability and the presence of psychotic symptoms as well as whether the client has a place to live or sources of social support (1,2,3).

In studies of public attitudes, perceived dangerousness strongly predicted support for mandated mental health treatment, but mandated treatment was more strongly endorsed for persons with drug dependence than for persons with other mental disorders (4,5; Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Angell B, unpublished manuscript, 2004). Among the general public, support for mandated treatment is related to viewing persons as being responsible for their condition (4; Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Angell B, unpublished manuscript, 2004). Persons with substance use disorders are viewed as being more responsible for their condition than persons with other psychiatric diagnoses (6). Our study determined whether attributions of responsibility for mental illnesses predict psychiatrists' mandated treatment recommendations.

Methods

In 2002 a survey was mailed to all 888 members of the Illinois Psychiatric Society. The surveys were confidential; each survey was numbered, and we matched those numbers to each recipient's name and address to send a reminder postcard to nonrespondents. The first page of the survey described Illinois' legal requirements for psychiatric commitment, including a reasonable expectation of endangerment to self or others (7). Illinois does not have a separate commitment statute for substance abuse. Informed consent was waived with approval from the University of Chicago institutional review board.

The survey presented vignettes about two men who had chronic mental illness. One vignette character was increasingly unable to meet his basic needs, whereas the other was increasingly aggressive toward his mother. Diagnoses varied between survey questionnaires: in an individual questionnaire, both of the vignette characters had the same disorder, but the disorder varied among the questionnaires—chronic schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or substance use disorder. Respondents rated the appropriateness of committing each vignette character in four scenarios of escalating risk of harm: not yet begun to deteriorate, showing deficits but not at imminent risk of harm, in danger but not at imminent risk of harm, and at imminent risk of harm. Attributions of personal responsibility for the onset and recurrence of the three mental illnesses were assessed. Participants also responded to statements about clinician beneficence and client autonomy. Demographic and professional practice information were also collected.

Commitment recommendations by type of threat of harm were collapsed at each level of harm. The sum of these variables formed an aggregate score for recommending involuntary hospitalization, the dependent variable in bivariate analyses of demographic characteristics, attributions of responsibility, and views about providing care. Significant bivariate relationships between the main dependent variable and other variables were then analyzed in a multivariate regression. Repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) examined differences in recommendations to hospitalize across levels of risk of harm and across personal attributions of responsibility.

Results

A total of 432 psychiatrists responded, giving a response rate of 49 percent. A majority of respondents were men (291 respondents, or 69 percent), with a mean±SD age of 54±12 years. For the past five years 157 respondents (38 percent) did not file any papers for involuntary hospitalization, 132 (32 percent) were involved in one or two cases a year, and 127 (31 percent) were involved in three or more cases a year. (Data were not available for all questions, so denominators other than 432 were used to calculate percentages.)

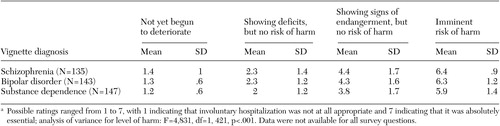

As Table 1 shows, as the vignette's description of risk of harm escalated, endorsements of involuntary hospitalization increased (p<.001). Hospitalization endorsements were stronger for vignettes that depicted schizophrenia or bipolar disorder than for those that depicted substance dependence (F=6.56, df=2, 421, p<.01, Tukey's honest significant difference [HSD], p<.05), which interacted with increasing levels of risk of harm (F=3.65, df=2, 421, p<.05).

Respondents viewed persons with mental illness as significantly more responsible for the illness' recurrence as for its onset, regardless of diagnosis (p<.001, paired-means t tests). However, persons with substance dependence were seen as more responsible than persons with other disorders for both the onset and recurrence of their condition (repeated measures ANOVA; onset: F=705.7, df=2, 804, p<.001; recurrence: F=543.4, df=2, 798, p<.001). No significant relationship was found between commitment recommendations and attributions of responsibility for the diagnoses.

In a multivariate regression analysis three views of clinician beneficence and client autonomy were significantly related to respondents' decision to hospitalize (F=7.27, df=9, 346, p<.001). Respondents were significantly more likely to endorse hospitalization if they agreed that mental health providers must ensure that clients' basic needs are met (p<.05), but they were significantly less likely to endorse hospitalization if they agreed that mental health providers should honor the client's right to refuse treatment (p<.001) or that psychiatrists cannot predict the future and so should wait for actual harm to occur (p<.05).

In addition, respondents who had filed for involuntary hospitalization three or more times per year tended to attribute greater responsibility to individuals for the recurrence of their mental illnesses (Tukey's HSD, p<.01).

Discussion

Severity of the risk of harm and psychiatric diagnosis significantly influenced psychiatrists' endorsements of involuntary hospitalization, mirroring previous research findings (1,2,4,5; Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Angell B, unpublished manuscript, 2004). Our study suggests that psychiatrists in Illinois are very reluctant—or may regard it as futile—to attempt to hospitalize an individual against his or her will until psychiatrists perceive a clear and imminent risk of harm. This practice is more stringent than Illinois state law, which allows involuntary hospitalization if individuals with mental illnesses are "reasonably expected to inflict serious harm on themselves or another in the near future." If the vignette recommendations can be assumed to reflect actual treatment decisions, then Illinois psychiatrists are not committing individuals to mandatory treatment even when the law allows them to do so.

Although members of the general public tended to recommend involuntary treatment for persons with substance dependence more frequently than for persons with other psychiatric diagnoses (5), the opposite trend was found among psychiatrists in our study. This result is consistent with previous findings in which respondents without psychiatric experience were more likely than psychiatrists or substance abuse counselors to recommend coercion for persons with substance dependence (8,9). These findings may reflect psychiatrists' conviction, based on clinical experience, that persons with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder usually respond well to treatment in a psychiatric hospital setting, whereas psychiatric hospitalization for individuals with substance dependence is ineffective and thus inappropriate.

No relationship was found between attributions of responsibility for any particular diagnosis and endorsement of involuntary commitment for vignette characters with that diagnosis, suggesting that psychiatrists' attributions of responsibility do not predict their treatment decisions. Even though psychiatrists' experience with involuntary hospitalization was not correlated with their vignette commitment recommendations, it was related to attributions of responsibility. The more frequently respondents filed for involuntary hospitalization in the past five years, the more frequently they attributed responsibility to individuals for the recurrence of mental illness.

It should be noted that the survey was completed by members of the Illinois Psychiatric Society; therefore, the results may not generalize to all practicing psychiatrists. Also, because the study participants responded to hypothetical commitment scenarios, some practical factors that may impinge on actual decision making—such as availability of resources—were not considered in our study.

Conclusions

In the absence of imminent harm, psychiatrists surveyed were hesitant to involuntarily hospitalize patients with mental illness. No relationship was found between attributions of responsibility and willingness to commit persons with mental illnesses.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a research infrastructure support program grant (MH-62198) from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors acknowledge the reviews and comments provided by John Monahan, Ph.D., Patrick W. Corrigan, Psy.D., and Amy C. Watson, Ph.D.

Dr. Luchins, Ms. Cooper, and Dr. Hanrahan are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Chicago, MC 3077, 5841 South Maryland Avenue, Chicago, Illinois 60637 (e-mail, acooper@ yoda.bsd.uchicago.edu). Dr. Rasinski is affiliated with the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago.

|

Table 1. Recommendations (mean±SD ratings) for involuntary hospitalization of 432 psychiatrists who responded to a survey that presented scenarios of escalating risk of harm to self or othersa

a Possible ratings ranged from 1 to 7, with 1 indicating that involuntary hospitalization was not at all appropriate and 7 indicating that it was absolutely essential; analysis of variance for level of harm: F=4,831, df=1, 421, p<.001. Data were not available for all survey questions.

1. Appelbaum PS, Hamm RM: Decision to seek commitment: psychiatric decision making in a legal context. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:447–451, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bagby RM, Thompson JS, Dickens SE, et al: Decision making in psychiatric civil commitment: an experimental analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:28–33, 1991Link, Google Scholar

3. Kullgren G, Jacobsson L, Lynöe N, et al: Practices and attitudes among Swedish psychiatrists regarding the ethics of compulsory treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 93:389–396, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Corrigan PW, Markowitz FE, Watson AC, et al: An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44:162–179, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Pescosolido BA, Monahan J, Link BG, et al: The public's view of the competence, dangerousness, and need for legal coercion of persons with mental health problems. American Journal of Public Health 89:1339–1345, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, et al: Stigmatizing attributions about mental illness. American Journal of Community Psychology 28:91–102, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities Code. Illinois Compiled Statutes, chapter 405, § 5Google Scholar

8. Wild TC, Newton-Taylor B, Ogborne AC, et al: Attitudes toward compulsory substance abuse treatment: a comparison of the public, counselors, probationers, and judges' views. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy 8:33–45, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Roberts C, Peay J, Eastman N: Mental health professionals' attitudes towards legal compulsion: report of a national survey. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 1:71–82, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar