The Independent Living Scales as a Measure of Functional Outcome for Schizophrenia

Abstract

The Independent Living Scales (ILS) measures cognitive skills required for independent living and is intended to provide guidelines for appropriate supervision requirements for persons in residential placement. To assess the validity of the ILS among persons with schizophrenia, the instrument was administered to 162 individuals with schizophrenia who were living in three gradations of care: maximum supervision, moderate supervision, and minimal supervision. Scores on the ILS differed significantly across the three levels of care, whereas scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) that were provided by clinicians discriminated only two levels of care. The ILS can be used among patients with schizophrenia to measure cognition as it affects functional outcome.

It is now widely accepted that cognitive impairment in the areas of memory, attention, and problem solving influences functional outcome among patients with schizophrenia, accounting for 20 to 60 percent of the variance in successful psychosocial rehabilitation, social problem-solving ability, or community living (1,2). Because cognition plays such a significant role in schizophrenia, clinicians and researchers need assessment tools that measure cognition as it affects functional outcome. Several questionnaires assess performance of independent living skills on the basis of information obtained from informants, self-report, or observation of simulated everyday functioning tasks (3,4,5,6). Although these measures of functional capacity discriminate outpatients from control subjects, they may not be applicable to inpatients, and they do not link cognitive skills to functional ability.

Assessments that focus on skills do not take cognitive functioning into account. For example, one can observe the skill of how a utility bill is paid, but if the importance of paying utility bills is not appreciated, or if the person forgets about the bill, payment will not be sent. Similarly, if an individual lacks initiative to perform the task without the structured demands of clinical observation, there is no functional application in a real-life context.

The Independent Living Scales (ILS) (7) assesses cognition as it affects daily functioning, but it has not been widely used in psychiatric populations. We evaluated whether the ILS was good at predicting the living status of inpatients and outpatients with schizophrenia. We also compared the instrument with the familiar clinician-rated Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) to determine whether the cognitive problem-solving measure would discriminate functional levels better than a clinically driven global measure.

Methods

The study participants were from outpatient and chronic inpatient settings in New York City, carried a DSM-IV axis I diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and were aged 18 to 55 years. The inpatients were potential research participants in a previous study, recruited from September 1996 to August 1998 (8). The outpatients were recruited from FEGS (Federation Employment and Guidance Services) from June 1998 to November 1998. Individuals were excluded from participation if they did not speak English, had a neurologic or serious medical disability, had severe behavioral disturbances, or had an IQ lower than 70.

The ILS assesses the likelihood of successful independent community living. The instrument, which was originally developed for adults with dementia, has been used to estimate the competence of adults with a diagnosis of a psychiatric illness, including schizophrenia.

The ILS has five subscales and two factor-analyzed subscales. "Memory-orientation" contains items that include orientation to time and place, recall of a brief shopping list, and recognition of a missing object. "Managing money" includes concrete tasks designed for monetary calculations and budgetary precautions. "Managing home and transportation" tests abilities to use the telephone and public transportation as well as home management skills. "Health and safety" assesses awareness of health problems, medical emergencies, and potential hazards around the home. "Social adjustment" reflects the individual's concerns and attitudes about interpersonal relationships. The performance-information factor subscale reflects actual knowledge or skills used to perform tasks—for example, using a telephone book or making change.

The problem-solving factor subscale (ILS-PB) comprises 33 items across all subscales that evaluate abstract reasoning and judgment required for daily living. Sample items are "What would you do if your lights and television went out simultaneously?" and "What would you do if you unintentionally lost ten pounds in a month?" We chose to focus on the ILS-PB in order to assess functional capacity as it relates to the underlying cognitive skills.

The ILS-PB takes 20 to 25 minutes to administer. As reported in the ILS manual, standardized scores ranging from 20 to 39 suggest maximum (full-time) supervision for daily living, scores from 40 to 49 suggest moderate supervision, and scores from 50 to 63 suggest minimum supervision, or independent living. Psychometric properties of the ILS-PB suggest that this subscale maintains the integrity of the ILS in its entirety (alpha coefficient=.86, test-retest reliability=.90, interrater reliability=.98, concurrent validity based on tests of social reasoning—for example, r=.65 with WAIS-R Comprehension). Discriminant validity tests found significant differences between nonclinical and clinical samples.

GAF scores, rated on DSM-IV axis V, are used to assess the overall level of psychosocial functioning for both inpatient and outpatient psychiatric patients. Ratings range from 0 to 100, based on a hypothetical continuum of mental health comprising psychological, social, and occupational functioning based on behavioral and symptom-oriented descriptions.

We recruited participants as part of a larger study described elsewhere (2). Written informed consent was obtained according to the research protocols approved by the institutional review boards at the respective sites. Clinical psychiatrists who treated study participants assigned GAF scores in charts but were blind to the study design. The ILS-PB was independently administered and scored by a trained psychologist.

Each participant's current functional level was coded from chart information before the ILS was administered. Three levels of supervision (living status) were delineated for community functioning: maximum supervision (24-hour hospitalization or staff supervision), moderate supervision (daily contact with staff or significant others in a residential program or family care setting), and minimum supervision (intermittent contact with case managers, presence of roommates, or living alone in an unsupervised apartment).

Results

A total of 162 patients were interviewed (61 women, or 38 percent, and 101 men, or 62 percent). The sample comprised 87 inpatients (54 percent) and 75 outpatients (46 percent). Fifty-three patients had a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder (33 percent), and 109 had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (67 percent). The mean±SD age of the participants was 37.2±8.3 years. All participants were persistently ill and had a history of continuous care for close to two years. Further demographic characteristics of this sample are reported elsewhere (2).

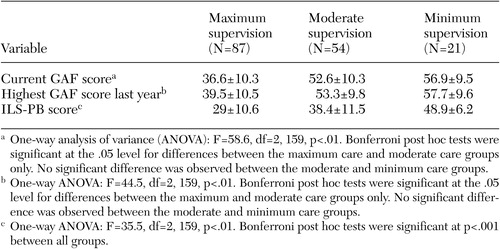

GAF and ILS-PB scores for the three living status groups are shown in Table 1. Lower GAF scores were observed among individuals who required maximum supervision. However, no significant differences in GAF scores were found between the moderate- and minimum-supervision groups.

Persons who required maximum supervision were more deficient in daily problem-solving skills, whereas the minimum-supervision group approached the recommended ILS-PB cutoff score of 50 for independent living.

Significant differences on ILS-PB scores were found between all groups.

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study indicate that the ILS-PB successfully discriminates three levels of functional outcome. The problem-solving skills demonstrated on the ILS were significantly predictive of living status. The clinically driven global measure (GAF) discriminated only two levels of need for supervision—maximum supervision and moderate supervision. This finding suggests that cognitive skills are more sensitive than symptoms for discriminating functional status, a viewpoint consistent with the results of previous research that found GAF more strongly correlated with clinical symptoms than functioning per se (9).

Because the ILS-PB specifically addresses daily problem-solving skills, it is an appropriate instrument for aftercare follow-up among persons with severe mental illness as they make the transition from an institutional setting (inpatient care) to community living (outpatient care). Although it is unlikely that a single instrument could meet the multiple demands for obtaining outcomes data across a variety of settings, we believe that the ILS-PB warrants further consideration as a measure that links cognition to functional outcome.

Dr. Revheim is affiliated with the program in cognitive neuroscience and schizophrenia of the Nathan S. Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, 140 Old Orangeburg Road, Orangeburg, New York, 10962 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Medalia is with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York.

|

Table 1. Mean±SD scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) and the problem-solving factor subscale of the Independent Living Scales (ILS-PB), by living status, among 162 patients with schizophrenia

1. Green, MF, Kern, RS, Braff, DL, et al: Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the "right stuff"? Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:119–136, 2000Google Scholar

2. Revheim N, Medalia A: Verbal memory, problem-solving skills, and community status in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 68:149–158, 2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Dickerson F: Assessing clinical outcomes: the community functioning of persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:897–902, 1997Link, Google Scholar

4. Dickerson FB, Origoni AE, Pater A, et al: An expanded version of the Multnomah Community Ability Scale: anchors and interview probes for the assessment of adults with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 39:131–137, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, Tauber R, et al: The Independent Living Skills Survey: a comprehensive measure of the community functioning of severely and persistently mentally ill individuals. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:631–658, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, et al: UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:235–245, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Loeb PA: ILS: Independent Living Scales Manual. San Antonio, Tex, Psychological Corp, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1996Google Scholar

8. Medalia A, Revheim N, Casey M: Remediation of memory disorders in schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 30:1451–1459, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Roy-Byrne P, Dagadakis C, Unutzer J, et al: Evidence for limited validity of the revised Global Assessment of Functioning Scale. Psychiatric Services 47:864–866, 1996Link, Google Scholar