Effect of an Educational Pamphlet on Help-Seeking Attitudes for Depression Among British South Asian Women

Abstract

South Asian women suffer disproportionately high rates of suicide and attempted suicide. Yet few intervention studies on this group have been done. A total of 180 British South Asian women were sampled to pilot test an educational pamphlet about depression and suicidality. After reading the pamphlet, significantly more women assessed themselves as willing to confide in their clinicians, friends, and spouses if they felt depressed or suicidal, rather than not telling anyone. Also, more women reported that they felt that antidepressants were helpful for depression after they read the pamphlet. These changes remained four to six weeks later. The pamphlet was feasible for use in primary care and community settings and highly acceptable among British South Asian women and professionals.

The term South Asian refers to persons whose ethnic origins are from countries of the Indian subcontinent. As reviewed elsewhere, disproportionately high rates of suicide and attempted suicide have been found among South Asian women who live in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Singapore, Malaysia, regions of India, and the United Kingdom; the highest rates have been found among young women (1). In the United Kingdom, British South Asian women are 1.6 times as likely to attempt suicide and are about twice as likely to complete suicide as white women (2,3).

Despite this disproportionate risk, there is a persistent scarcity of educational materials about depression and suicidality in South Asian communities. This lack of information is part of a larger problem of insufficient psychiatric research about interventions for depression and suicidality, especially among minority groups (4). South Asians form the largest minority group in the United Kingdom (5); they are America's third-largest Asian group, numbering 2.1 million (6). Because of this unmet need in the South Asian population, our exploratory study sampled British South Asian women to pilot test an educational pamphlet about depression and suicidality to determine the pamphlet's feasibility, acceptability, and effect on help-seeking attitudes.

Methods

Our study received ethical approval from the Institute of Psychiatry and was carried out between April and July 1999. We drew a convenience sample of South Asian women from nine general practitioner clinics and 24 South Asian community organizations in London. Participants' ages ranged from 15 to 75 years. The research assistant was South Asian and fluent in English, Hindi, and Urdu. Recruitment from general practitioner clinics took place in waiting rooms for general outpatient, mother and baby, and antenatal clinics. General practitioners required that their staff recruit patients, a limitation that we accepted so that we would be able to include primary care patients. The research assistant used membership lists of community organizations to recruit participants by mail and by telephone.

The pamphlet was developed after focus groups of South Asian women were conducted (1,7). Entitled For All Asian Women and Asian Families: Creating Harmony, Preventing Despair, the pamphlet provided information about recognizing depression and the risk of suicide, preventing suicide attempts, treating depression, using various coping mechanisms, and finding sources of help. The pamphlet fit on a two-sided sheet of paper for easy, inexpensive copying. Copies of the pamphlet and its subsequent translations into Urdu, Hindi, Punjabi, and Gujarati are available from the authors and the United Kingdom Department of Health (7). Our study was conducted in English, so that we could test the pamphlet on an adequate sample of younger, English-speaking, British South Asians, who are at high risk of suicide and attempted suicide (2).

We used a prospective, cohort, time-series design. Participants were given a self-report questionnaire packet along with a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Participants sequentially read and completed the four parts of the packet before returning it by mail. The four sections consisted of a consent form; a baseline questionnaire on demographic characteristics, help-seeking attitudes for depression and suicidality, and treatments that could help depression; the educational pamphlet; and a second questionnaire meant to be completed after the participant read the pamphlet that repeated the baseline questions. Baseline questions had been pilot tested among British South Asians (8) and were derived from a national survey on depression in the United Kingdom (9).

Participants were sent a follow-up questionnaire four to six weeks later, which repeated the baseline questions to test the pamphlet's longer-term impact on help-seeking attitudes. Participants who did not return the follow-up questionnaire were contacted by mail and telephone.

Intercooled Stata 5.0 software was used. Significance tests were two-tailed, and confidence intervals were 95 percent. McNemar's chi square test was used for matched, paired, categorical variables to analyze changes in individuals' responses over time.

Results

Of the 298 British South Asian women who were invited to participate in our pilot test, 180 agreed and 118 refused to participate (40 percent). Ninety-seven participants (54 percent) were sampled from community organizations, and 83 (46 percent) were from general practitioner clinics. Of the 180 women who completed the baseline questionnaire, 160 (89 percent) completed the follow-up questionnaire. The mean±SD age of the participants was 35±13.2 years. More details about our study are provided elsewhere (1,7).

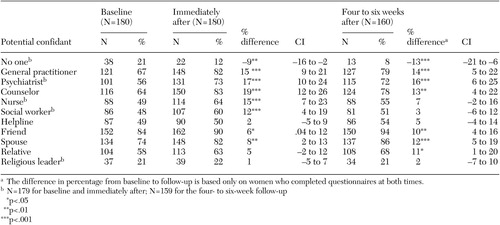

Table 1 shows the impact of the educational pamphlet on baseline help-seeking attitudes. Both immediately and four to six weeks after reading the pamphlet, women said that they were more likely to report feelings of depression and suicidality to health professionals, friends, and family. At baseline, 38 women (21 percent) said that they would not tell anyone about their feelings of depression or suicidality. This number fell to 13 women (8 percent) at the four- to six-week follow-up. Participants who completed the four- to six-week follow-up questionnaire and those who did not had the same baseline help-seeking attitudes and the same degree of attitude change immediately after reading the pamphlet.

This pattern of significant improvement occurred for both the primary care sample and the community sample. Among participants from community organizations, reading the pamphlet increased the proportion of women who said that they would confide in a general practitioner by 21 percent (49 out of 90 women at baseline to 68 out of 90 women who completed the four- to six-week follow-up; 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=11 to 34 percent, p<.001).

Regarding treatment attitudes, 91 women (51 percent) agreed at baseline that antidepressants were helpful for depression. This number increased to 105 women (66 percent) at the four- to six-week follow-up (CI=6 to 24 percent, p<.001). Recent immigrants were the least likely to state that they felt that antidepressants were helpful for depression. Among recent immigrants (32 women) the pamphlet increased the reported acceptance of antidepressants by 28 percent (eight women at baseline to 17 women immediately after reading the pamphlet; CI=7 to 49 percent, p<.01).

The pamphlet was well-received by professionals from general practitioner clinics and community organizations as well as by our study participants. In fact, we often received requests to translate the pamphlet for wider availability. More than 90 percent of participants liked the pamphlet and thought that it was useful for increasing community awareness. Facilities adopted the pamphlet and its translations for general use and stated that it filled an important gap in South Asian public health.

Discussion and conclusions

Our pilot study was small, with a nonrandom sample and a broad age range, which limited the power and validity of our analysis. We did not ask participants if they had experienced depression or suicidality themselves. These factors, along with the lack of information on women who refused to participate, render our findings preliminary, with a probable self-selection bias. Whether the improved help-seeking attitudes would alter the participants' behavior and reduce suicide attempts is unknown. Verification would require a large, prospective study. Our study was a preliminary exploration of practical approaches for addressing suicidality and depression among South Asian women. Requests by participants and professionals for the pamphlet's translation suggest good face validity for use with South Asian women who are not fluent in English. But the effectiveness of the translated versions remains to be tested.

The pamphlet was well accepted, could be cheaply and easily disseminated, and addressed an important service priority. It positively changed women's help-seeking attitudes in both primary care and community settings. General practitioners could expect the pamphlet to increase patients' acceptance of antidepressant treatment and referrals to counselors or psychiatrists. The pamphlet increased women's willingness to report depression and suicidality to general practitioners, thus increasing opportunities for support, diagnosis, and treatment. By reducing the large proportion of South Asian women who would not confide in anyone, the pamphlet could be useful for reaching emotionally isolated women at risk.

Our study integrated the recommended stages in developing a complex intervention (10): qualitative fieldwork and focus groups as well as tests of feasibility, of acceptance by providers and patients, and of the effect in real-world settings. Within this framework, our pilot intervention addressed a persistent gap in the needs of British South Asian women who experience a high risk of suicide and attempted suicide.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from the United Kingdom Department of Health. The authors thank Dr. Morven Leese for statistical advice and Dr. Jayashree Singh for valuable assistance.

The authors are affiliated with the department of health services research of the Institute of Psychiatry in London. Send correspondence to Dr. Hicks at the South London and Maudsley National Health Service Trust, Tamworth Road Resource Centre, 37 Tamworth Road, Croydon Surrey CR0 1XT, United Kingdom (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Percentage of British South Asian women who said that they were likely to tell potential confidants if they were depressed or had suicidal thoughts before, immediately after, and four to six weeks after reading an educational pamphlet

1. Hicks MH, Bhugra D: Perceived causes of suicide attempts by UK South Asian women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 73:455–462, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bhugra D, Desai M, Baldwin DS: Attempted suicide in west London: I. rates across ethnic communities. Psychological Medicine 29:1125–1130, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Neeleman J, Mak V, Wessely S: Suicide by age, ethnic group, coroners' verdicts, and country of birth: a three-year survey in inner London. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:463–467, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wittchen HU: Epidemiological research in mental disorders: lessons for the next decade of research—the NAPE Lecture 1999. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 101:2–10, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Census 2001: National Report for England and Wales. London, United Kingdom, Stationary Office, 2003Google Scholar

6. Barnes JS, Bennett CE: The Asian Population:2000. Washington, DC, US Census Bureau, 2002Google Scholar

7. Bhugra D, Hicks MH: Deliberate self-harm in Asian women: an intervention study. London, United Kingdom, Department of Health, 2000Google Scholar

8. Bhugra D, Baldwin D, Desai M: A pilot study of the impact of fact sheets and guided discussion on knowledge and attitudes regarding depression in an ethnic minority sample. Primary Care Psychiatry 3:135–140, 1997Google Scholar

9. Priest R, Vize C, Roberts M, et al: Lay people's attitudes to treatment of depression: results of an opinion poll for Defeat Depression campaign just before its launch. British Medical Journal 313:858–859, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al: Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. British Medical Journal 321:694–696, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar