Brief Reports: A Program to Reduce Use of Physical Restraint in Psychiatric Inpatient Facilities

Abstract

The authors describe a program to reduce the use of physical restraint on three psychiatric units of a university hospital. One component of the program involved interviewing patients to determine their stress triggers and personal crisis management strategies. The second consisted of training staff members in crisis deescalation and nonviolent intervention. During the first two quarters after implementation of the program, physical restraint rates declined significantly and remained low on all three units for the remainder of the year after implementation. Hospitals should consider instituting comprehensive staff training that encourages adaptive patient behaviors and nonviolent staff intervention to reduce the physical and mechanical restraint of children and adults in inpatient facilities.

The national mental health system is experiencing a cultural shift whereby the use of restraint and seclusion is being severely curtailed or eliminated altogether by psychiatric inpatient facilities. Because of numerous well-publicized reports of deaths of psychiatric inpatients while they were in restraints and growing public concerns about patient safety, recent regulations mandate that such coercive measures be used solely in emergencies after less restrictive alternatives have failed. Relevant research indicates the usefulness of multilevel approaches to reduce the use of restraint (1). Some of these interventions draw on techniques, such as altering organizational policies (1,2), providing specialized staff training (1,2), and teaching patients self-management strategies, including anger control (3), adaptive behaviors (4,5), and interpersonal self-awareness and symptom reduction (6,7). We describe a program to reduce the use of restraint that was implemented on three psychiatric units of a university hospital: one unit served youths aged 12 to 17 years, another served a general adult population, and the third served adults enrolled in clinical trials.

Two components constitute the restraint reduction program. An advance crisis management component helps patients to determine personal stress triggers and strategies that can be used to manage agitation or anger (8). The premise of this component is that patients' unique crisis management techniques can be used during hospitalization (4) if these techniques are documented before crises occur (8). The nonviolent crisis intervention component—which was developed by Crisis Prevention Institute, Inc., in Brookfield, Wisconsin—teaches staff members about factors that precipitate crises and nonviolent methods for managing aggressive behaviors (9).

To collect crisis management information, staff members conducted brief interviews at intake or within the first 24 hours of admission to elicit patients' crisis triggers and to determine deescalation strategies. Events that led to agitation and escalation in the past were discussed, after which patients' unique calming techniques were identified. Next, patients' restraint histories were elicited along with their medication preferences.

Information from the interview was used to create a unique crisis management plan for each patient. One copy was given to the patient and another was stored in an easily available desktop organizer on each unit that contained patient information. Each plan was reviewed on a weekly basis during regular unit meetings of nurses, physicians, aides, and residents. Deescalation strategies were discussed with individual patients, both informally and after critical incidents occurred.

If a youth or an adult experienced difficulty managing symptoms or if his or her emotions began to escalate, staff members immediately implemented the crisis management plan for that individual, using his or her unique strategies to avert a crisis. If the patient's primary calming strategy could be performed independently by the patient, he or she was reminded of the strategy and encouraged to use it. Staff assistance was provided as needed.

If a crisis was averted, staff members and the patient reviewed the crisis management plan and determined which strategies were most effective. If a crisis was not averted and the person was restrained, a staff-patient debriefing occurred after the patient was released from restraint. This debriefing involved discussing the events precipitating the restraint, as well as any needed revisions to the patient's plan. If revised, the patient's new plan was presented to all staff members during the next unit meeting.

The clinical research unit implemented the crisis management component in July 2001 and the nonviolent crisis intervention component in October 2001. The adolescent psychiatry unit and the general psychiatry unit implemented the two components of the program in October 2001. Although hospital management and nursing leadership were making changes to organizational policies and procedures regarding the new program, staff members were trained in crisis management and nonviolent crisis intervention techniques. To learn the mechanics of the crisis management component, staff members from all three units studied a comprehensive training manual and viewed a 90-minute training video, which are part of a seclusion and restraint reduction toolkit (10). The head nurse and the director of quality assurance attended the meetings to provide information and answer questions. To learn about the nonviolent crisis intervention component, staff members participated in a one-day training session that was developed by the Crisis Prevention Institute. The results of the evaluation of this new program are described below.

Methods

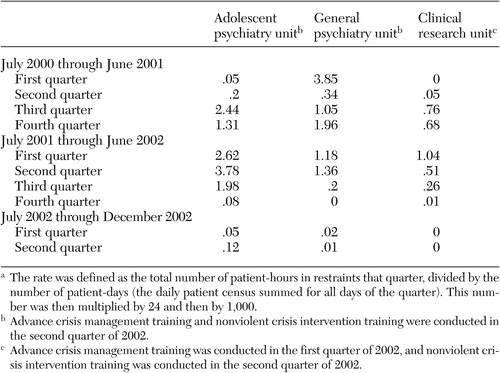

Quarterly restraint data from the hospital's quality improvement department were examined for July 2000 through December 2002—approximately one year before and one year after the program was introduced in all three units. Restraint rates were calculated with a formula that was designed to allow for comparison with another hospital's inpatient psychiatry units for purposes of quality assurance. The rate was defined as the total number of patient-hours in restraints that quarter, divided by the number of patient-days (the daily patient census summed for all days of the quarter). This number was then multiplied by 24 and then by 1,000.

Results

From July 2000 to December 2002 a total of 1,602 patients were treated in the general psychiatry unit and 308 patients were treated in the clinical research unit. On these two units, a majority of the patients had diagnoses of schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders (336 patients, or 21 percent, on the general unit; 160 patients, or 52 percent, on the research unit) or mood disorders (1,266 patients, or 79 percent, on the general unit; 132 patients, or 43 percent, on the research unit). Approximately half were white (929 patients, or 58 percent, on the general unit; 166 patients, or 54 percent, on the research unit), about half were female (913 patients, or 57 percent, on the general unit; 142 patients, or 46 percent, on the research unit); most were unemployed (1,298 patients, or 81 percent, on the general unit; 212 patients, or 69 percent, on the research unit), most had never been married (833 patients, or 52 percent, on the general unit; 212 patients, or 69 percent, on the research unit), and a majority had prescriptions for medications at the time of admission (1,202 patients, or 75 percent, on the general unit; 259 patients, or 84 percent, on the research unit).

A total of 227 patients were treated in the adolescent psychiatry unit from July 2000 to December 2002. On the adolescent unit, 84 patients (37 percent) had a diagnosis of major depression or a depressive disorder, 57 (25 percent) had an adjustment disorder, 34 (15 percent) had a conduct disorder, 16 (7 percent) had schizophrenia or a psychotic disorder, and 36 (16 percent) had another diagnosis. A total of 141 patients (62 percent) were African American, 150 (66 percent) were female, and 141 (62 percent) had prescriptions for medications.

As shown in Table 1, the adolescent unit experienced a 48 percent decrease in the restraint rate one quarter after training occurred and a 98 percent decrease two quarters after the training. The rate remained low throughout the final two quarters of the year. The general psychiatry unit experienced an 85 percent decrease in restraint rate one quarter after the training and a 99 percent decrease two quarters after the training. Once again the rate remained low during the final two quarters of the evaluation period. The clinical research unit experienced a 51 percent decrease in the restraint rate in the quarter after crisis management training and a 49 percent decrease in the quarter after nonviolent crisis intervention training. In the two quarters after both trainings had occurred, the rate declined by 98 percent and remained low (at zero) for the final two quarters. Before the restraint reduction program was implemented, restraint rates on the adolescent unit and clinical research units had been climbing and the general psychiatry unit's rates had fluctuated considerably. A two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that there was a significant effect of training (F=8.31, df=1, 26, p<.01) but no significant difference between units in the effect of training.

Discussion and conclusions

Analysis of administrative data showed significant reductions in the use of restraint after the introduction of the restraint reduction program. Restraint rates declined by 97 to 99 percent and remained low throughout the remainder of the year after training occurred. Moreover, staff members and patients found the procedures easy to use and expressed high satisfaction with the results.

Our evaluation had several limitations. Because this was not a controlled study, we could not definitively tie the reduction in restraint rates to the training intervention. Reductions may be due to selection bias, regression to the mean, changes in staff members' attitudes, specific unit environments, or other organizational or programmatic factors. In addition, we could not verify that crisis management or nonviolent crisis intervention procedures were used correctly and consistently, although all new staff members were trained immediately after their hiring and retraining occurred annually. We also could not separate the potentially unique effects of the nonviolent crisis intervention versus crisis management procedures because two of the units introduced these procedures together. However, the unit that implemented them separately experienced a significant decrease in restraint rates immediately after implementing the crisis management procedure but before implementing the nonviolent crisis intervention procedure, and no differences by unit were found in a two-way ANOVA. Also, no changes in any of the units' medication prescribing practices occurred during or after the program's introduction.

These findings have important clinical implications and suggest areas for future research. Involving patients and staff members in a partnership of safety may subsequently reduce the occurrence of restraint among both adolescent and adult inpatients. Our findings also support the need for more rigorous evaluation of the intervention's effectiveness and the satisfaction of staff members and patients with noncoercive alternatives to restraint.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research, U.S. Department of Education, and the Center for Mental Health Services, and by cooperative agreement H-133B-000700 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Ms. Jonikas, Dr. Cook, and Dr. Kim are also with the Center on Mental Health Services Research and Policy at the University of Illinois at Chicago, 104 South Michigan Avenue, Suite 900, Chicago, Illinois 60603 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Quarterly rates of restrainta among patients in three psychiatric units before and after implemention of a restraint reduction program

1. Donat DC: An analysis of successful efforts to reduce use of seclusion and restraint at a public psychiatric hospital. Psychiatric Services 54:1119–1123, 2003Link, Google Scholar

2. Busch AB, Shore MF: Seclusion and restraint: a review of recent literature. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 8:261–270, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Allen JJ: Seclusion and restraint of children: a literature review. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 13:159–167, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Visalli H, McNasser G, Johnstone L, et al: Reducing high-risk interventions for managing aggression in psychiatric settings. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 11:54–61, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Donat DC: Impact of a mandatory behavioral consultation on seclusion/restraint utilization in a psychiatric hospital. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Design 29:13–19, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. DosReis S, Barnett S, Love RC, et al: A guide for managing acute aggressive behavior of youths in residential and inpatient treatment facilities. Psychiatric Services 54:1357–1363, 2003Link, Google Scholar

7. Copeland ME: Wellness Recovery Action Plan. Dummerston, Vt, Peach Press, 1997Google Scholar

8. Carmen E, Crane B, Dunnicliff M, et al: Massachusetts Department of Mental Health Task Force on the Restraint and Seclusion of Persons Who Have Been Physically or Sexually Abused: Report and Recommendations. Boston, Department of Mental Health, 1996Google Scholar

9. Jambunathan J, Bellaire K: Evaluating staff use of crisis prevention intervention techniques: a pilot study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 17:541–558, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Jonikas JA, Laris A, Cook JA: Increasing Self-Determination Through Advance Crisis Management in Inpatient and Community Settings: How to Design, Implement, and Evaluate Your Own Program. Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago National Research and Training Center on Psychiatric Disability, 2003Google Scholar