Characteristics of Violent Behavior in a Large State Psychiatric Hospital

Abstract

Violent behavior is a significant problem in psychiatric hospitals. The authors reviewed hospital incident reports to identify the characteristics of violent behavior in a large state psychiatric hospital. They found that a very small percentage of patients accounted for a majority of violent episodes, that rates of violent behavior varied among hospital units, that assaultive behavior was more common than self-harm in the long-term units, and that most commonly the assault victims were other patients. The data support earlier studies demonstrating that a small number of patients are responsible for a majority of violent episodes in a hospital setting.

Violence and aggression are significant problems in the psychiatric hospital setting. Violent behaviors often represent an important barrier to discharge to the community. A consistent finding has been that a small proportion of the hospital population is responsible for a disproportionately large proportion of violent episodes. These patients typically have a history of violence, have had multiple psychiatric hospitalizations, are younger, have neurologic impairments, have schizophrenia or personality disorders, and are involuntarily admitted to the hospital (1,2,3,4,5). In this brief report we present quantitative and descriptive data on violent behavior in a large state psychiatric hospital.

Methods

The study was conducted from October 1, 2001, through February 28, 2002, at Dorothea Dix Hospital, a 360-bed state psychiatric hospital located in Raleigh, North Carolina. During the study period, 1,952 patients were cared for at the hospital. Incident reports generated during this five-month period were reviewed. Reports of violent behavior included the identity of the aggressor and the victim, the type of aggressive behavior, and the hospital unit in which the incident occurred. Although "verbal violence," such as threats, has been considered a violent incident in other studies, such incidents were not included in our analysis.

A rate of violent behavior for each inpatient unit was calculated by dividing the number of violent episodes for each study month by the average monthly census during that month. The rate of violent behavior was calculated for five months for each inpatient unit. This rate was compared across inpatient units with use of one-way analysis of variance, with post hoc multiple pairwise comparisons using Tukey's honest significant differences (SYSTAT Version 10, SPSS Inc., 2000). A comparison of the proportion of self-injury and assaults against others as contributing to violent episodes was done by t test for both the acute and long-term adult units. Other findings were descriptive and were not subjected to statistical analysis.

Results

Persistently violent patients

A total of 419 violent episodes occurred during the five-month study period. Twenty-seven patients had five or more episodes of violent behavior during the study period. These patients accounted for 56 percent of all the violent episodes (236 of 419 episodes) but only 9 percent of the average daily census (27 of 307), or 1.4 percent of all patients served during the study period (27 of 1,952). Of these 27 patients, ten (37 percent) had a developmental disability (mental retardation or autism spectrum disorder), traumatic head injury, or other neurologic disorder, and seven (26 percent) had borderline or antisocial personality disorder. In addition, six patients (22 percent) were adolescents. The pharmacologic treatment of these patients has been described previously (6).

Violent episodes on inpatient units

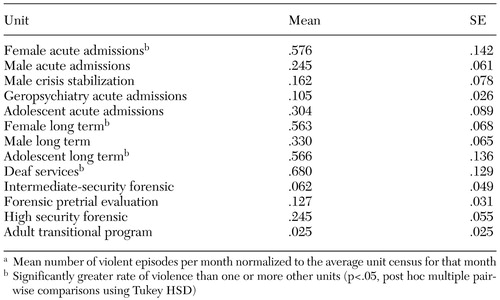

The average monthly rate of violent behavior for each hospital unit during the study period is shown in Table 1. Significant differences were found among the units (F=7.1, df=12, 52, p<.001), with post hoc analysis revealing the highest relative rates of violence on the female acute unit, the female long-term unit, the adolescent long-term unit, and the deaf services unit.

Hospitalwide, assault against others occurred in 266 episodes (63 percent), self-injury in 133 episodes (32 percent), and property destruction in 49 episodes (12 percent). We compared the types of violence toward persons (self-injurious behavior or assault on others) in the adult acute units and the adult long-term units. No difference was found between the proportion of episodes of self-injury and assault to others on the adult acute units (self-injury, .34±.16; assault, .52±.07; t=−1.8, df=4, p=.14). In contrast, a significantly greater proportion of episodes involved assault to others rather than to self on the adult long-term units (self-injury, .11±0.03; assault, .88±.01; t=−34.43, df=2, p<.001).

For 76 percent of the incident reports that detailed assaults (202 of 266), the identity of the victim was listed. We found that other patients were most likely to be the victim of assault (92 assaults, or 46 percent), followed closely by health care technicians (85 assaults, or 42 percent). Nurses were victims in another 20 assaults (10 percent). The remaining victims of assault (five assaults, or 2 percent) included one physician, one psychologist, one social worker, one recreation therapist, and one clerical staff worker.

Discussion and conclusions

The analysis of our hospital data revealed that 1.4 percent of patients who were treated during the study period accounted for 56 percent of all violent episodes. Of these patients, 63 percent had a developmental disability (mental retardation or autism spectrum disorders), traumatic head injury, other neurologic disorder, or personality disorder. Our findings are similar to those of other published studies (1,2,3,4,5).

When comparing rates of violence among inpatient units, we found that the female units, both acute and long term, had relatively higher rates of violence. This finding is consistent with that of an earlier study showing that female inpatients were more assaultive than male inpatients (7). The reason for this difference is unclear but may be related to the fact that the proportion of patients with personality disorders was higher on the female units or to a greater tendency to report violent events on the female units than on the male units, where such behavior might be somewhat expected. In addition, variance in rates among units might be explained by gender, differences in training and attitudes between individual staff members, physical layouts of the units, crowding effects, and the ward "culture of control"—for example, forensic versus nonforensic.

Although there was no difference between the types of physical harm to persons on the acute admissions units, assaultive behavior was much more common than self-harm on the long-term units. This finding is probably explained by the fact that patients who are assaultive against others are difficult to place in community settings; as a consequence, they may be overrepresented in the long-term inpatient units. Consistent with these data is the report by Citrome and colleagues (8) showing that assaultive patients had longer stays than patients at risk of self-harm. Together, these findings underscore the importance of developing specific treatments for violent behavior, in part to allow patients to live in less restrictive settings.

An important finding of this study was that other patients were most often the victims of inpatient violent assault. Given that other patients and health care technicians are more likely to be in close physical proximity to violent patients and that these two groups accounted for 88 percent of assault victims, proximity to and time spent with persistently violent patients should be considered risk factors for victimization.

A weakness of the study was the use of incident reports to determine the number of violent episodes, given that these reports may not always be filled out by hospital staff as required (9,10). However, our results and those of others suggest that staff are more likely to report the more significant violent events. Still, "subthreshold" violent events (including verbal hostility) that were not included in incident reports could have changed the relative rates of violence in different inpatient units, leading to a potential "reporting bias" in our data that may have varied among units.

Our finding that persistently violent patients were a heterogeneous diagnostic group further suggests that aggression may have a similar neurobiologic substrate regardless of diagnosis and may indeed represent a specific "aggressive" disorder. Because persistently violent patients are difficult to successfully place in community settings and represent a danger to other patients, the rapid identification of these assaultive patients and the use of careful pharmacologic trials targeted specifically toward aggressive behaviors are indicated. Because aggression may have distinct pharmacologic treatments, the early identification of persistently aggressive patients and the use of objective measurements of aggression—for example, the Overt Aggression Scale—to gauge treatment response should be encouraged.

The authors are affiliated with the Dorothea Dix State Psychiatric Hospital in Raleigh, North Carolina, and with the department of psychiatry of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Address correspondence to Dr. Kraus at 3601 Mail Service Center, Raleigh, North Carolina 27699-3601 (e-mail, [email protected]). A version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association held May 17 to 22, 2003, in San Francisco.

|

Table 1. Rate of violent behavior in specific hospital unitsa

a Mean number of violent episode per month normalized to the average unit census for that month

1. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al: Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1112–1115, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Owen C, Tarantello C, Jones M, et al: Repetitively violent patients in psychiatric units. Psychiatric Services 49:1458–1461, 1998Link, Google Scholar

3. Kennedy J, Harrison J, Hillis T, et al: Analysis of violent incidents in a regional secure unit. Medicine, Science, and the Law 35:255–260, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Fottrell E: A study of violent behaviour among patients in psychiatric hospitals. British Journal of Psychiatry 136:216–221, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Barber JW, Hundley P, Kellogg E, et al: Clinical and demographic characteristics of 15 patients with repetitively assaultive behavior. Psychiatric Quarterly 59:213–224, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kraus JE, Sheitman BB: Clozapine reduces violent behavior in heterogeneous diagnostic groups. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, in pressGoogle Scholar

7. Binder RL, McNeil DE: The relationship of gender to violent behavior in acutely disturbed psychiatric patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51:110–114, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

8. Citrome L, Green L, Fost R: Length of stay and recidivism on a psychiatric intensive care unit. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:74–76, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Brizer DA, Convit A, Krakowski M, et al: A rating scale for reporting violence on psychiatric wards. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:769–770, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Convit A, Isay D, Gadioma R, et al: Underreporting of physical assaults in schizophrenic inpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 176:507–509, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar