Psychosocial Risk Factors Associated With Suicide Attempts and Violence Among Psychiatric Inpatients

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: To better understand the relationship between suicidal behavior and violence directed toward others among patients with major psychiatric disorders, this study examined how suicide attempts and violent behaviors were associated with various psychosocial problems. METHODS: Participants were inpatients in two psychiatric state hospitals. They included 216 inpatients who had physically assaulted another patient or a staff member and a comparison group of 81 inpatients who had not assaulted anyone. History of suicide attempts and historical information about various risk factors for violence and suicide were obtained through chart review and patient interviews. RESULTS: Patients in the violent group did not differ from those in the nonviolent group in whether they had attempted suicide. Suicide attempts and violence were associated with different historical variables. Suicide attempts were associated with a history of head trauma, harsh parental discipline, and parental psychopathology. Violence against others was associated with having a history of school truancy and foster home placement. CONCLUSIONS: Among inpatients with major psychiatric disorders, violence and suicide attempts were not related to each other and were associated with dissimilar psychosocial risk factors.

Several studies have reported a relationship between violence and suicide. In one study, persons who attempted suicide had significantly higher scores for lifetime aggression than those who did not (1). Longitudinal investigations have demonstrated associations between suicide and self-reported aggression (2) and between suicide and hostility (3).

However, in the developmental literature, suicidal and violent behaviors have often been associated with two different types of underlying psychopathology: internalizing problems and externalizing behaviors. Internalizing problems, such as anxiety, depression, and somatization, are strongly associated with suicide. These actions stand in contrast to externalizing behaviors, which include violent and antisocial behaviors. The literature shows that different risk factors and developmental paths are associated with each type of psychopathology (4,5).

To better understand the occurrence of suicide and its relationship to violence, it is important to consider the psychosocial factors underlying suicide and violence, especially familial factors and early life events. The literature suggests that risks of suicidal and violent behaviors are associated with variables that relate to family dysfunction and various measures of childhood difficulties.

A higher incidence of suicide is seen among patients with substance use disorders (1,6). A history of head trauma has been associated with suicide, suicide attempts, and suicidal ideation (1,7,8,9,10). A recurrent finding from the literature is that individuals who engage in suicidal behaviors frequently have backgrounds that are characterized by various forms of dysfunction, including childhood physical abuse, poor parent-child relationships, and poor mental health of parents. Physical abuse as a child has been reported as a risk factor for suicidality in multiple studies (1,11,12). A review of 21 studies that examined the relationship between childhood abuse and suicidality later in life reported that all the studies found a significant relationship between childhood abuse and suicide attempts or suicidal ideation (13). Suicide has also been associated with the poor mental health of parents, including psychiatric disorders and a history of substance abuse (14,15).

Many of the above factors have also been associated with violence, including substance use disorders (16,17), head trauma (18,19), and physical abuse as a child (20). Truancy has been associated with antisocial behaviors and violence (21). In a study of a large cohort of adolescents, truancy was more common among participants who were reared in dysfunctional homes or showed early conduct problems (22). The extent of truancy was associated with other aspects of adolescent adjustment, including criminal activity during adolescence and having a substance use disorder.

Our study investigated the relationship between suicide attempts and physical assaults among inpatients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder. We wanted to evaluate the relative importance of various psychosocial risk factors for suicidal and violent behavior.

Methods

Sample

The participants included physically assaultive inpatients aged 18 to 55 years with major psychiatric disorders who were admitted to two psychiatric state hospitals from January 1991 to December 1994. Patients were considered to be violent if they had at least one physical assault directed at others, either patients or staff members, which consisted of actual physical contact, such as striking, kicking, slapping, or scratching. Patients with an incident of physical assault during their first two months of hospitalization were eligible for the study. Patients with mental retardation or neurologic illness were excluded from the study. DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders were diagnosed by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (23). This study was part of a larger investigation that examined the course of assaults among newly admitted patients over a four-week period (24).

A total of 265 patients met the above criteria over the four-year period. All these patients were approached after the first episode of physical assault for consent to participate in the study. Because 253 of these patients were given a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder, the sample for this study was further limited to these three diagnoses for greater homogeneity. Of these 253 patients, 15 refused to participate in the study and 238 agreed. We tried to match every other violent patient with a nonviolent patient on diagnosis, racial or ethnic background, gender, age (within five years), and duration of present hospitalization, but in some cases we were not able to find a matching nonviolent patient. Because the violent group constituted the main interest in the parent study, if we did not find a matching nonviolent patient, the violent patient was still entered in the study. The actual ratio of violent to nonviolent patients was 2.6. The group consisted of 238 patients in the violent group and 93 patients in the nonviolent control group. All participants provided informed consent. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the two participating institutions.

As described above, the main study entailed following the patients for four weeks. Suicide data and other background information were obtained at the end of that period, when the patients were more stable clinically and the information was more reliable. Twenty-two patients in the violent group (9 percent) and 12 patients in the nonviolent group (13 percent) did not complete the four weeks. Therefore, the final sample which provided the information needed for this study included 216 patients in the violent group and 81 patients in the nonviolent group. No differences were found between patients who completed the four weeks and those who did not in diagnosis, age, gender, and race or ethnicity. The main reason for noncompletion was discharge from the hospital.

The patients in the violent group and those in the nonviolent group were classified on the basis of lifetime history of any attempt at suicide. Patients were classified as suicide attempters if they had made any suicide attempt and as nonattempters if they had never made a suicide attempt.

Assessments

Assessment of violence. Physical assaults were defined as actual physical contact—for example, striking, kicking, or pushing. The assaults were assessed on a prospective basis by two licensed research nurses through daily review of nursing reports, patients' charts, and interviews with ward staff who were present at the time of the incidents. Intraclass correlation coefficients for interrater reliability for violence were obtained before the study and reconfirmed every six months throughout the duration of the study. The coefficients were above .90 throughout the study.

Assessment of suicide attempts. A suicide attempt was defined as a self-destructive act that was sufficiently serious to require medical evaluation and was carried out with the intent to end one's life. Lifetime history of suicide attempts was determined through a review of hospital charts and records. Full psychiatric, social work, and nursing assessments—which reviewed suicidal history—were available for all patients. This information was supplemented by patient interviews. Patients were asked whether they had ever attempted suicide or been hospitalized for a suicide attempt.

Psychosocial and background information. Demographic, medical, and psychosocial information were obtained through chart reviews and patient interviews. Information collected included mental health and psychiatric history as well as the history of criminal activities and community violence, substance use and substance abuse history, and head trauma.

We also obtained information about family functioning and childhood circumstances. To measure childhood circumstances, we selected indicator variables that spanned different aspects of childhood and family functioning. These variables included the history of school truancy, foster home placement, severe discipline in childhood that resulted in physical injury (harsh discipline), and parental psychopathology. Participants were asked whether they had experienced these various problems. Charts were reviewed for the same information. A participant was classified as having a history of the problem if a positive response to the question was obtained or if the chart indicated such a problem. Participants were classified as having a parental history of psychopathology if either one of their parents was reported to have a substance use disorder or a major psychiatric disorder that required psychiatric hospitalization. Harsh parental discipline was rated as positive if participants indicated that they were punished in a way that they bled or developed a welt. Foster home placement included any foster home placement until the age of 15 years.

The instrument was validated in an earlier study (25). Kappa values measured interrater agreement in terms of a binary (dichotomous) classification variable—that is, with the psychosocial factors rated as present or absent for a particular patient. The kappa values for these items were above .90.

Statistical analyses

Logistic regression models were used to study the relationship between suicide attempter status and the various psychosocial variables as well as the relationship between violence status and these variables. The classification of suicide attempters versus nonattempters was the dependent variable. The psychosocial variables, dichotomized into binary measures, were the independent variables. We included the classification as violent versus nonviolent as a covariate to investigate whether the associations between suicide and these psychosocial factors were independent of violence. Gender, diagnosis, race and ethnicity, and age were entered as covariates in all the analyses.

Similar analyses were done for the classification of patients as violent versus nonviolent. That classification served as the dependent variable, the psychosocial variables were the independent variables, and suicidal classification, gender, diagnosis, race and ethnicity, and age were used as covariates.

The odds ratio showed the strength of the relationship between the dichotomous (yes or no) risk factors and suicide attempter status and between the risk factors and violence status.

In addition to the above analyses, in order to investigate whether patients who were both suicidal and violent differed from those who were only suicidal or only violent, we ran logistic regressions with the psychosocial variables as the dependent variables. For independent variables, we used the classifications as suicide attempters versus nonattempters, as violent versus nonviolent, and the interaction between these two classifications. We also included gender and diagnosis as covariates. This interaction between the two classifications tested whether the combination of suicide and violence was associated with different psychosocial variables.

Results

Overall characteristics of the suicidal and nonsuicidal groups

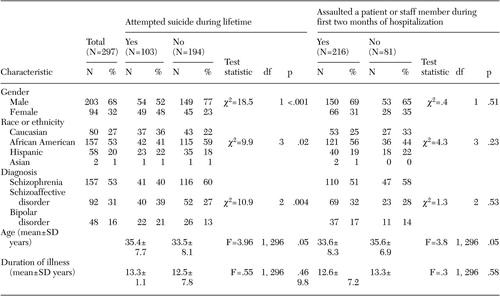

As mentioned above, the final sample consisted of 297 participants: 216 in the violent group and 81 in the nonviolent group. Of these 297 patients, 103 (35 percent) had a history of suicide attempts and 194 (65 percent) did not. Among patients who attempted suicide, 47 (46 percent) had two or more suicide attempts. Table 1 shows the demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the 297 patients characterized on the basis of both suicide attempts and violent behavior.

Persons who attempted suicide differed significantly from those who did not in gender, race or ethnicity, diagnosis, and age. However, those who attempted suicide did not differ from those who did not in duration of illness. A higher proportion of women than men, of Caucasians than African Americans, and of patients with schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder than of patients with schizophrenia had a history of attempting suicide. Persons who attempted suicide were older than those who did not. Patients in the violent group differed from those in the nonviolent group in age but not in the other characteristics, reflecting the fact that they had been matched successfully on all characteristics but age. The age difference, although significant, was small.

Logistic regression was used with suicide classification as the dependent variable, and gender, race or ethnicity, diagnosis, and age were used as the independent variables. When these variables were considered together, gender was the only variable that remained significantly different between persons who attempted suicide and those who did not (Wald's χ2=11.2, df=1, p<.001). A larger proportion of women than men attempted suicide. Gender appeared to be the most robust variable associated with attempted suicide in this population.

We investigated the possibility that the patient population differed in the two hospitals. The populations were similar in diagnostic distribution, gender, and age, but they differed in racial and ethnic distribution (χ2=8.1, df=3, p=.04). We found relatively more Caucasian patients in one hospital than in the other (52 patients, or 34 percent, compared with 28 patients, or 20 percent) and correspondingly fewer African American patients (71 patients, or 46 percent, compared with 85 patients, or 59 percent). The distribution of Hispanic and Asian patients was similar in both hospitals.

Relationship between violent behaviors and suicide attempts

The violent and nonviolent groups did not differ in the percentage of patients who had a history of suicide attempts: 33 percent of the nonviolent group (27 of 81 patients) and 35 percent of the violent group (76 of 216 patients) had a history of suicide attempts. Furthermore, in the violent group no difference was found in the total number of physical assaults over the four-week period between persons who attempted suicide (76 patients; mean±SD number of physical assaults, 2.53±1.96) and those who did not (140 patients; mean number of physical assaults, 2.63±2.58).

History of physical assaults in the community was evaluated as a discrete variable. No relationship was found between community violence and suicide; 33 percent of the persons who attempted suicide (34 of 102 patients) versus 28 percent of those who did not (53 of 191 patients) had a history of community violence.

Psychosocial factors associated with violence and suicide attempts

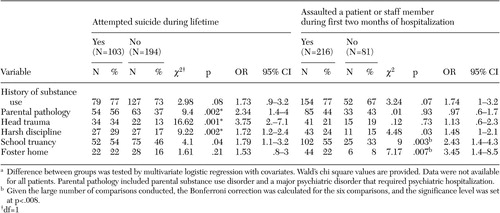

Table 2 shows the results of analyses that used classification as a suicide attempter as the dependent variable. The violence classification served as a covariate in the analyses, as described above. In addition, age, gender, race or ethnicity, and diagnosis were introduced as covariates. We also entered the hospital as a covariate, but results were essentially unchanged and this variable was not retained in the final analyses.

Table 2 also shows the results of analyses that used classification as assaultive during the first two months of hospitalization as the dependent variable. The analyses were similar to those that were performed for the suicide attempter classification. Correction for multiple testing was introduced for the six variables, and p=.008 was accepted for significance.

As shown in Table 2, head trauma, excessive childhood physical discipline that resulted in physical injury, and parental psychopathology—including parental substance use disorders and major psychiatric disorders that required psychiatric hospitalization—were significantly higher among patients with a history of suicide attempts compared with those without such a history. No significant difference was found between the two groups in foster home placement, and the difference in school truancy was not significant once the results were adjusted for multiple testing.

History of school truancy and foster home placement were higher among patients in the violent group than among those in the nonviolent group. The two groups did not differ significantly in parental psychopathology, head trauma, and harsh discipline once the results were adjusted for multiple testing.

Similarly, the associations of suicide attempts and physical violence with alcohol and substance use were not statistically significant after the results were adjusted for multiple testing.

The odds ratios presented in Table 2 provide information about the degree of association (effect size) between these variables and suicide attempts and between these variables and violence (each classification was used as a covariate for the other).

As mentioned above, to investigate whether patients who were both suicidal and violent differed from those who were only suicidal or only violent, we ran logistic regressions in which the interaction between the violence and suicide classifications was introduced as an independent variable. None of the interactions between the two classifications was significant; the combination of suicide and violence was not associated with different psychosocial variables.

Discussion

No relationship was found between suicide attempts and inpatient violence. Approximately one-third of patients in the violent group and one-third of patients in the nonviolent group had attempted suicide at some point in their lives. No relationship was found between suicide attempts and community violence. These findings are at variance with some of the results that have been reported in the literature (1,2,3). To some extent this discrepancy may be due to differences in diagnoses and severity of illness. The association between suicide attempts and violence has been found to be most prominent among participants with personality disorder, especially borderline personality disorder (26). Mann and colleagues (1), for example, noted that a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder and aggression were both robust predictors of suicide attempter status but that the two were strongly interdependent and could not be separated from each other. Patients in our study were given diagnoses of major psychiatric disorders, and a majority had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Furthermore, they presented with a severe illness, given that they were recruited while inpatients in state psychiatric facilities.

The principal aim of this study was to identify psychosocial factors associated with violence and factors associated with suicide attempts. In investigating the relationship between these factors and violence, we used the suicide classification as a covariate. Similarly, we included the violence classification as a covariate when investigating the relationship between these factors and suicide attempts.

Harsh discipline, parental psychopathology, and head trauma were strongly associated with suicidal behavior, whereas school truancy and foster home placement were strongly associated with violent behavior. Harsh discipline and school truancy were associated with both suicide attempts and violence, but the association between harsh discipline and violence and between truancy and suicide attempts was not significant once results were adjusted for multiple testing.

These variables exert their influence through a complex interplay between biological and environmental factors. Some, such as head trauma, may influence later behavioral problems and psychopathology primarily through physiologic mechanisms. Others, such as parental psychopathology, may be associated with behavioral problems through diverse mechanisms, including genetic transmission or environmental mechanisms, such as the impact of the parents' maladaptive behaviors and ineffective or harmful parenting strategies (27,28). School truancy and foster home placement are indicative of environmental and familial instability. Children in foster care have extensive histories of maltreatment and family dysfunction (29,30).

As mentioned above, head trauma has been associated with both violence and suicide in the literature, but the association is greater with suicide. In general epidemiologic studies both suicide and depression are reported as common sequelae of head trauma (8,9,10).

Foster home placement is indicative of disruption of the family setting. This instability may necessitate a greater degree of independence and fighting to survive. This socialization, which emphasizes self-assertion, may place the children at higher risk of externalizing problems, including violent behaviors, rather than internalizing problems. Youths who describe themselves as anxious and fearful were less likely to describe themselves as "combat-ready" or to have engaged in aggressive and other antisocial behavior (31).

The results of the study reported here should be interpreted in light of the limitations of the study design. This study was conducted in state hospitals with patients with severe mental disorders. Therefore, the results may not be generalized to suicidal and violent behaviors in less severely ill populations. Another limitation is the retrospective nature of the suicidal behavior and psychosocial factors. Although extensive records were available for most patients and this information was complemented by patient interviews, some information may have been missing. To ensure greater homogeneity and to obtain more reliable data for all patients, the psychosocial information could not be sufficiently thorough. Thus, although we obtained information about parental psychiatric hospitalization and parental substance use disorders, the exact diagnosis of the parents and their history of suicide attempts could not be ascertained. A further limitation is the absence of a measure of impulsivity. Impulsivity has been associated with both violence and suicide; its inclusion would have provided better understanding of the relationship, or lack of it, with the various psychosocial factors. Further study is needed to explore these issues more fully to provide a better understanding of suicidal and violent behaviors with these psychosocial factors. Also, because the study was conducted more than ten years ago, DSM-III-R was used. However, for the diagnostic categories considered in this study, there have been few changes in criteria between DSM-III-R and DSM-IV.

Conclusions

In this study of psychiatric inpatients with severe mental illness, no relationship was found between suicide attempts and various forms of assaults directed at other people. There were, for the most part, different psychosocial risk factors for the two sets of behavior. Parental psychopathology and head trauma were more likely to be associated with suicide attempts, whereas foster home placement and school truancy played a more important role for physical assaults directed at others.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by grant R01-MH-58341 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Krakowski is affiliated with the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, 140 Old Orangeburg Road, Orangeburg, New York 10962 (e-mail, [email protected]). He is also affiliated with the department of psychiatry at New York University in New York City. Dr. Czobor is with the Nathan Kline Institute and with DOV Pharmaceuticals in Hackensack, New Jersey.

|

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of 297 state hospital inpatients, classified in terms of suicide attempts and violence against others

|

Table 2. Psychosocial variables among 297 state hospital inpatients, classified in terms of suicide attempts and violence against othersa

a Difference between groups was tested by multivariate logistic regression with covariates. Wald's chi square values are provided. Data were not available for all patients. Parental pathology included parental substance use disorder and a major psychiatric disorder that required psychiatric hospitalization.

1. Mann JJ, Waternaux C, Haas GL, et al: Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:181–189, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Angst J, Clayton P: Premorbid personality of depressive, bipolar, and schizophrenic patients with special reference to suicidal issues. Comprehensive Psychiatry 27:511–531, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Romanov K, Hatakka M, Keskinen E: Self-reported hostility and suicidal acts, accidents, and accidental deaths: a prospective study of 21,443 adults aged 25–59. Psychosomatic Medicine 56:328–336, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Campbell SB: Behavior problems in preschool children: a review of recent research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 36:113–149, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Cicchetti D, Toth SL: A developmental perspective on internalizing and externalizing disorders, in Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology: Vol 16: Internalizing and Externalizing Expressions of Dysfunction. Edited by Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1991Google Scholar

6. Roy A, Linnoila M: Alcoholism and suicide. Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviors 16:244–273, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lishman WA: The Psychological Consequences of Cerebral Disorder. Oxford, England, Blackwell Scientific, 1987Google Scholar

8. Simpson G, Tate R: Suicidality after traumatic brain injury: demographic, injury, and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine 32:687–697, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lewin W, Marshall TF, Roberts AH: Long-term outcome after severe head injury. British Medical Journal 2:1533–1538, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Teasdale TW, Engberg AW: Suicide after traumatic brain injury: a population study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 71:436–440, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Van der Kolk BA, Perry JC, Herman JL: Childhood origins of self-destructive behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:1665–1671, 1991Link, Google Scholar

12. Shaunesey K, Cohen JL, Plummer B, et al: Suicidality in hospitalized adolescents: relationship to prior abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 63:113–119, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Santa Mina EE, Gallop RM: Childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult self-harm and suicidal behaviour: a literature review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 43:793–800, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Garfinkel BD, Froese A, Hood J: Suicide attempts in children and adolescents. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:1257–1261, 1982Link, Google Scholar

15. Kienhorst CWM, de Wilde EJ, van den Bout J, et al: Self-reported suicidal behavior in Dutch secondary education students. Suicide Life Threatening Behaviors 20:101–112, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

16. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393–401, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Monahan J, Steadman, HJ, Silver E, et al: Rethinking Risk Assessment: The MacArthur Study of Mental Disorder and Violence. New York, Oxford University Press 2001Google Scholar

18. Grafman J, Schwab K, Warden D, et al: Frontal lobe injuries, violence, and aggression: a report of the Vietnam head injury study. Neurology 46:1231–1238, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Silver JM, Kramer R, Greenwald S, et al: The association between head injuries and psychiatric disorders: findings from the New Haven NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Brain Injury 115:935–945, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Weiss B, Dodge, KA, Bates JE: Some consequences of early harsh discipline: child aggression and a maladaptive social information processing style. Child Development 63:1321–1335, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Berg I: When truants and school refusers grow up. British Journal of Psychiatry 141:208–210, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ: Truancy in adolescence. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 30:25–37, 1995Google Scholar

23. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Patient Version (SCID-P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1990Google Scholar

24. Krakowski M, Czobor P, Chou JC: Course of violence in patients with schizophrenia: relationship to clinical symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25:505–517, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Krakowski M, Convit A, Volavka J: Patterns of inpatient assaultiveness: effect of neurological impairment and deviant family environment on response to treatment. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology 1:21–29, 1988Google Scholar

26. Brodsky BS, Malone KM, Ellis SP: Characteristics of borderline personality disorder associated with suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154:1715–1719, 1997Link, Google Scholar

27. Downey G, Coyne JC: Children of depressed parents: an integrative review. Psychological Bulletin 108:50–76, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Rutter M, Silberg J, O'Connor T: Genetics and child psychiatry: empirical research findings. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 40:19–55, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. A Blueprint for Fostering Infants, Children, and Youth in the 1990's. Washington, DC, Child Welfare League of America, 1991Google Scholar

30. Zuravin SJ, DePanfilis D: Factors affecting foster care placement of children receiving child protective services. Social Work Research 21:34–42, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Schwab-Stone M, Chen C, Greenberger E: No safe haven. II: The effects of violence exposure on urban youth. Journal of the American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:359–367, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar