Association Between Seclusion and Restraint and Patient-Related Violence

Abstract

This study assessed the effect of an intervention designed to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint on reported episodes of patient-related violence on an acute inpatient psychiatric service. Results showed a significant decrease in the total number of episodes of seclusion and restraint between the 12 months before and after the intervention. However, the number of episodes of assault on patients and staff increased significantly. Efforts to decrease seclusion and restraint may be accompanied by an increased risk of harm to psychiatric patients and staff, and intensive safety monitoring and staff training should accompany all such efforts.

Despite advances in the management of acute psychiatric disorders, violent behaviors among psychiatric inpatients remain common and vexing clinical occurrences. Suicidal behaviors, assaults on patients, and attacks on psychiatric staff are often considered separately for reporting purposes, but together they represent serious, potentially preventable adverse events that occur on inpatient psychiatric units (1). Although patient-related violence remains problematic, mandates from the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare (CMS) and the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) have emphasized the need to respect patients' autonomy by minimizing the use of seclusion and restraint in both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric settings.

Few studies have examined the effectiveness of these recent mandates in terms of patient outcomes. Staff training has been emphasized in an effort to reduce the use and enhance the safety of seclusion and restraint (2). Little is known about the correlation, if any, between efforts to reduce seclusion and restraint and occurrences of patient-related violence. At least one study found that the use of seclusion and restraint increased as the frequency of violence rose (3). Another report of a performance improvement project to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint found an 18.8 percent reduction in staff injuries as seclusion and restraint were reduced (4). This study investigated the effect of a program to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint on the frequency of all episodes of patient-related violence.

Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of an intervention to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint on three acute inpatient psychiatric units in a large inner city community hospital. Patients in this hospital tend to be poor; are insured primarily through Medicaid or Medicare; tend to have severe and persistent mental illness, most often in the context of dual diagnosis; and are frequently admitted involuntarily. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center, but because the study used retrospective aggregate data, informed consent was not obtained.

The intervention was compatible with the mandates of JCAHO and included staff education, the addition of the history of inpatient violence to admission forms, continuous nursing monitoring to minimize the duration of episodes of seclusion and restraint, postepisode debriefing of the staff and the patient, and a review of each episode by the senior nurse and a physician. The intervention centered on early recognition of signs of agitation among patients and early clinical intervention. All staff members had previously been trained on assault prevention measures; however, this training varied and specific training on violence prevention was not given during the study period.

The total number of episodes of seclusion and restraint in the 12 months before and after the intervention was determined by examining the 2000 and 2001 central nursing log books of the department of psychiatry. Episodes of violence against patients and staff and episodes of self-destructive behavior were determined from incident report files. Other-directed violence was defined as any event in which there was unwanted physical contact with intent to harm (5). Self-directed violence included deliberate episodes of self-mutilation or suicidal acts. The total number of admissions and patient days were obtained from hospital administrative databases.

Results

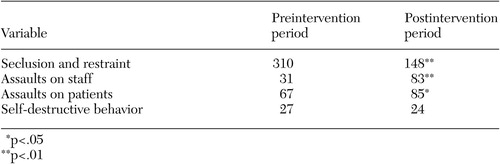

A significant decrease (52 percent reduction) was seen in the total number of episodes of seclusion and restraint from the 12 months before to the 12 months after the intervention (χ2=37.01, df=2, p<.001). As shown in Table 1, the number of episodes of assaults on staff increased significantly, from 31 in the preintervention period to 83 in the postintervention period (χ2=31.9 df=2, p<.001). The number of episodes of assaults on patients also increased significantly, from 67 in the preintervention period to 85 in the postintervention period (χ2=5.52 df= 2, p<.05). The number of episodes of self-destructive behavior did not differ significantly. The number of admissions (1,766 preintervention and 1,602 postintervention) and total patient days (27,726 preintervention and 24,030 postintervention) were not significantly different between the two periods. The frequency of the violent incidents was distributed evenly throughout the 12 months after the intervention and did not cluster either immediately after the training period or near the end of 12 months after the training period.

In addition, no changes were seen before and after the intervention in the type of psychiatric population served, the staff-to-patient ratio, the privilege status of patients, and the method of reporting incidents. Furthermore, no changes were made to the physical space on the inpatient units that might have accounted for the increased rate of assault.

Discussion and conclusions

This study showed that an intervention designed to reduce seclusion and restraint on three acute inpatient psychiatric units was associated with a significant increase in other-directed patient violence during the 12 months after the intervention. This finding is at variance with previous reports (3). Our study suggests that efforts to decrease seclusion and restraint may be accompanied by an increased risk of harm to psychiatric patients and staff.

The implemented intervention and training may have enabled the staff to use different strategies that contributed to a significant decrease in the rate of seclusion and restraint. Also, staff members may have felt that they were prohibited from using seclusion or restraint, thus resulting in a significant reduction in the rate of seclusion and restraint. However, staff did not receive any specific training in the management of violent patients, which may have increased the rate of assaults on staff members and diminished their ability to reduce other-directed assaults.

The generalizability of these findings may be limited by the uniqueness of the population and by the type and duration of the intervention. Other potential limitations of the study included the absence of data on the frequency of use of prescription and nonprescription medication and other intervention strategies, such as the use of time-outs. The absence of this data makes it difficult to assess whether these factors contributed to the reduction of seclusion and restraint. It is also possible that, in response to frustration over increased violence, the staff overreported violent incidents. Although our qualitative investigations of the incidents make this possibility unlikely, this limitation cannot be entirely ruled out. Nonetheless, the findings of this study indicate that reducing seclusion and restraint may not be without risk. Therefore, intensive safety monitoring and staff training should be included in all such efforts.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center and with Albert Einstein College of Medicine, 1276 Fulton Avenue, Bronx, New York 10456 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Total number of episodes of seclusion and restraint and patient-related violencein the 12 months before and after an intervention designed to reduce the use ofseclusion and restraint

1. Shah AK, Fineberg NA, James DV: Violence among psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 84:305–309, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Fisher WA: Restraint and seclusion: a review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1584–1591, 1994Link, Google Scholar

3. Owens C, Tarantello C, Jones M, et al: Violence and aggression in psychiatric units. Psychiatric Services 49:1452–1457, 1998Link, Google Scholar

4. Forster P, Cavness C, Phelps M: Staff training decreases use of seclusion and restraint in an acute psychiatric hospital. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 13:269–271, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Flannery R, Irvin E, Penk W: Characteristics of assaultive psychiatric inpatients in an era of managed care. Psychiatric Quarterly 70:247–256, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar