Clinical Characteristics of Community Forensic Mental Health Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Community forensic mental health teams are a new service within the widening range of specialized community mental health services. The characteristics of these novel services are poorly defined. Two commonly described service models in the United Kingdom are the integrated model (forensic specialists working within community mental health teams) and the parallel model (forensic specialists working on a separate specialist team). The study reported here aimed to establish clear definitions of these service models. METHODS: A literature review and a focus group of ten service professionals were conducted to identify candidate characteristics of services in community forensic mental health teams. A total of 31 characteristics were identified and used to prepare the first-round questionnaire for the two rounds of a modified Delphi consultation, which is an expert opinion and consensus method, with a multidisciplinary panel of 32 mental health professionals experienced in community forensic work. RESULTS: Twenty-nine staff (91 percent) completed the two rounds of consultation. Thirteen service characteristics differentiated the integrated and parallel models. Key characteristics of parallel teams included having their own team base, separate referral meetings, a specialist management line, specialist supervision, protected funding, forensic psychology, good links with criminal justice systems, and capped caseloads. Integrated teams were distinguished by their close links with community mental health services and acceptance of more referrals from primary care. CONCLUSIONS: Integrated and parallel models of community forensic mental health teams differ on many service characteristics. Defining these characteristics will help in researching the pros and cons of each model in the treatment and risk management of mentally ill offenders in the community.

Concerns about the risk of violence associated with mental illness have increased in the wake of high-profile homicides by persons with mental illness (1). These cases and subsequent inquiries prompted the search for more effective models of care for mentally ill offenders in the community (2).

In the United Kingdom, specialized teams for early-onset psychosis, home treatment, crisis intervention, and specialized community forensic mental health teams have been established (3). The development of increasing numbers of specialist services in response to deinstitutionalization pressures (4,5) has attracted controversy, with critics citing the lack of evidence for greater efficacy (6) as well as concern about cost-effectiveness and potential detrimental effects on core generic mental health services (7). Research into the effectiveness of some specialized community mental health services—for example, assertive community treatment—has had conflicting results, possibly due to problems with treatment fidelity and the stage of development of other community-based mental health services (8,9,10,11).

Two main models of specialist community forensic mental health services have been described in the United Kingdom: parallel and integrated. In the parallel service, specialist forensic staff working in a separate team carry out assessments and act as case managers. In the integrated model, forensic specialists work on generic community mental health teams to perform these roles (3). These services have, in most cases, evolved in an ad hoc manner, mainly through clinical pressures to manage mentally ill offenders, and they have not relied on an evidence base or on well-defined theoretical models as the basis for service development.

The use of the terms "parallel" and "integrated" is sometimes confusing, because these are not well-defined service models (12). Available descriptions indicate that the parallel model provides an autonomous multidisciplinary specialist service (3). Under the integrated model, specialist workers operate as members of a general community mental health team. The absence of clear definitions for each service model is an obstacle to research into the efficacy of specialist community forensic teams.

In this exploratory study, we hypothesized that it would be possible to distinguish these two models on the basis of service characteristics. This study aimed to identify the characteristics that distinguish the two models by using a modified Delphi consultation (13).

Methods

Delphi consultation

The Delphi consultation method, developed by the RAND Corporation in the 1950s (13), is used to obtain consensus, especially in areas in which there is little other evidence. Members of a panel of experts anonymously respond to specific questions about a particular problem. Their responses are analyzed and fed back to the same experts in the next consultation round. This iterative consultation provides an opportunity for the experts to reevaluate their opinions in light of the average ratings of the group (14). The result of a Delphi consultation is a composite of the group's expert knowledge. The three main features of the method are anonymity, iteration, and controlled feedback (15). The method has been effectively used to identify the components of assertive community treatment (11,16) and to determine the threshold of severity of mental illness in making decisions about access to mental health services (17).

A literature search informed the questions for the Delphi consultation. The search used MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and OVID, using the terms "forensic," "community." and "mental health." We also hand searched for relevant cross-referenced articles. Using information abstracted from the literature review, we developed a list of candidate categories for defining integrated and parallel service models, including staffing, supervision arrangements, organization of referral meetings, links with other services, and the method of funding. The study was conducted between September 2002 and June 2003.

A focus group was then conducted to validate the preliminary characteristics identified from the literature review and to identify other characteristics of community forensic teams. The ten-member group included three forensic psychiatrists, three forensic nurses, two service managers, one forensic psychologist, and one general psychiatrist who worked closely with forensic teams from local services. The focus group discussions were audiotaped, transcribed, and analyzed to identify the themes that indicated the service characteristics of the two models. Focus group participants were asked to comment on a written summary of the discussion and to provide terms or phrases to label the key characteristics of the two service models. This approach ensured that the terminology used in the questionnaire came from the participants. In the first-round questionnaire we applied the 31 service characteristics separately to both integrated and parallel models, resulting in a total of 62 statements. This approach enabled the panelists to rate the two models on each of the characteristics separately. The items were rated on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 indicating never; 2, occasionally; 3, sometimes and sometimes not; 4, most of the time; and 5, always. The questionnaire was piloted to ensure conceptual clarity and wording of the questions.

The panel members were selected from around England from specialist forensic teams and generic teams with forensic specialists from local services and through a snowballing sampling technique, to identify professionals who had at least five years of experience working with mentally ill offenders in the community. We chose this method rather than constituting this panel randomly to help ensure that the panel had specialist expertise in managing mentally ill offenders in the community.

Results

The Delphi consultation panel comprised 32 mental health professionals, including eight who had participated in the focus group. There were eight community forensic workers (community psychiatric nurses or social workers), 12 forensic psychiatrists, four service managers, four forensic psychologists, and four general psychiatrists with experience in managing forensic patients.

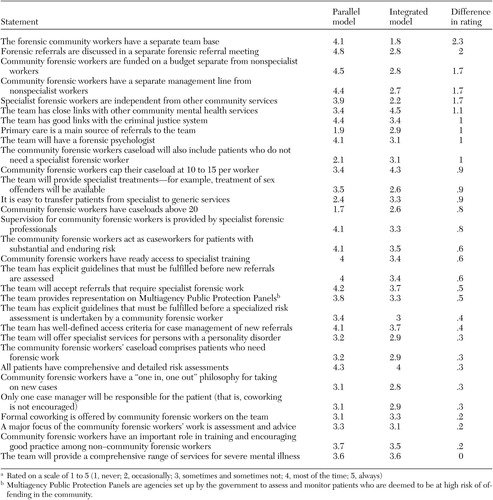

Twenty-nine participants (91 percent) completed the first round of consultation. The mean scores for the 31 original candidate characteristics are shown in Table 1.

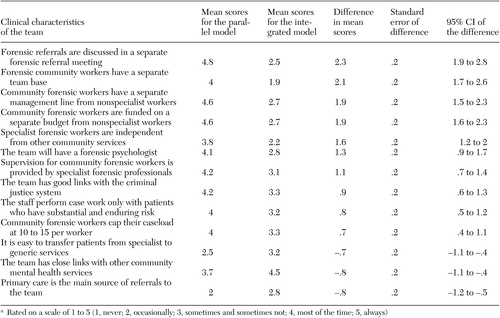

In order to focus on items that differentiated the two models, we used an arbitrary cutoff of a difference of at least .8 in the mean scores between the two models, and 16 items were deleted from the questionnaire. The researchers collectively agreed that items with smaller differences in mean ratings would not be helpful in further differentiating the two models in the second round of consultation. The panel members were asked to rate the remaining 15 items again. On the basis of the standard Delphi method, the second-round questionnaire showed the mean ratings from all participants as well as their own scores from the first round for each item. All 29 participants who completed the first round of consultation also completed the second round; t tests were used to examine the differences between each of the characteristics in the two models, and 13 items showing significant differences were obtained.

Analysis of the second-round scores (Table 2) showed that the panel judged that parallel teams were characterized by having a separate referral meeting, a separate team base, specialist team managers, specialist supervision, specialist forensic psychology staff, small caseloads, protected budgets, more access to protected funding and training opportunities, good links with the criminal justice system, and separation from other community services. Integrated teams were characterized as having better access to community resources and services, being more likely to receive referrals from primary care, and having greater ease of transfer between services. The differences between all 13 items were significant (p<.001). The differences and the confidence intervals from the second round are shown in Table 2.

Discussion and conclusions

Our results indicate that parallel and integrated teams are characterized by differences in physical location, management, caseload, staffing, referral procedures, and liaison with criminal justice agencies. It can be hypothesized that parallel teams will be able to deliver a more specialized treatment program to a selected group of patients (3). However, there is a concern that this service model may discourage nonforensic clinicians from developing important violence risk assessment and risk management skills. Clinicians operating in integrated teams may have a beneficial role in disseminating forensic skills to nonforensic colleagues, but they may find it difficult to utilize and maintain their specialist skills when much of their work is with nonforensic patients and when there is a lack of forensic clinical supervision. These hypotheses are worth exploring in future clinical trials. Outcome measures should include violence, dissemination of skills, and delivery of evidence-based treatments.

Although specialist services attract enthusiastic and highly skilled staff and although client satisfaction may be high, the long-term cost-effectiveness of such services is yet to be established (6). We focused on the evaluation of specialized community interventions for mentally ill offenders. It is important to have a consensus on the distinguishing characteristics of each model before undertaking research as to which model of care offers the most cost-effective risk management and permit clinical staff to deliver specialized clinical interventions for high-risk individuals. This study concentrated on differences rather than similarities between models, because these differences are likely to account for the superiority of one or the other clinical service when the models are compared. Although the study concentrated on forensic teams, the methodology may also be applicable to the evaluation of other specialized mental health teams.

In selecting the panel, we deliberately chose a group of experienced multidisciplinary staff, in keeping with the guidelines for the Delphi consultation method (18). The individual items were generated by a focus group of experienced professionals, thus covering all relevant service areas. We did not further operationalize the variables in this study, which could be considered a limitation. However, rigid definitions may be less generalizable, especially in the world of forensic mental health, where there are major differences in the organization of mental health and criminal justice services between jurisdictions (19). Nor did we include items such as specialist supervision and training, referral guidelines, specialist risk assessments, coworking (when clinicians from two different teams jointly undertake case work with a patient), and specialist treatments in the second round, because we did not expect these items to differentiate the two models further. These items may have additional utility in studying outcomes of these service models.

The two models that were compared in this study may perhaps be unique to the United Kingdom. A recent survey of forensic teams across England and Wales (20) indicated that about 80 percent of community forensic mental health teams considered themselves to follow a parallel model of working. However, it is likely that, in practice, the models followed by different forensic teams across England and Wales are a hybrid of parallel and integrated models (3,21). The findings of this study are being used to define and monitor fidelity to the service model in a comparison of integrated and parallel community forensic teams that is currently under way. We hope that the service characteristics identified in the study reported here will be relevant in other jurisdictions in which services are being developed and evaluated (19).

Acknowledgments

This study was part of a research project funded by the UK Department of Health. The authors thank Alec Buchanan, M.D., for his comments.

Dr. Mohan and Dr. Fahy are affiliated with the section of forensic mental health at the Institute of Psychiatry, P.O. Box 25, London SE5 8AF, United Kingdom (e-mail, r.mohan @iop.kcl.ac.uk). Dr. Slade is with the department of health services research at the Institute of Psychiatry.

|

Table 1. Mean ratings of statements of first-round consultation in a sample of 29 service professionals, ranked in order of differencea

a Rated on a scale of 1 to 5 (1, never; 2, occasionally; 3, sometimes and sometimes not; 4, most of the time; 5, always)

|

Table 2. Rank-ordered differences in average ratings of characteristics of parallel and integrated service models after second-round consultation in a sample of 29 service professionalsa

a Rated on a scale of 1 to 5 (1, never; 2, occasionally; 3, sometimes and sometimes not; 4, most of the time; 5, always)

1. Appleby L, Shaw J, Amos T: National confidential inquiry into suicide and homicide by people with mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry 170:101–102, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Monahan J, Bonnie RJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Mandated community treatment: beyond outpatient commitment. Psychiatric Services 52:1198–1205, 2001Link, Google Scholar

3. Snowden P, McKenna J, Jasper A: Management of conditionally discharged patients and others who present similar risks in the community: integrated or parallel? Journal of Forensic Psychiatry 10:583–596, 1999Google Scholar

4. Thornicroft G, Bebbington P: Deinstitutionalisation: from hospital closure to service development. British Journal of Psychiatry 155:739–753, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Lamb HR, Bachrach LL: Some perspectives on deinstitutionalization. Psychiatric Services 52:1039–1045, 2001Link, Google Scholar

6. Burns T: Generic versus specialist mental health teams, in Textbook of Community Psychiatry. Edited by Thornicroft G, Szmukler G. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 2001Google Scholar

7. Burns T: To outreach or not to outreach. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry 12:13–17, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Stein LI, Test MA: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392–397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Burns T, Creed F, Fahy T, et al: A randomised controlled trial of outcome of intensive versus standard case management for severe psychotic illness: the UK700 case management trial. Lancet 353:2185–2189, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Fiander M, Burns T: A Delphi approach to describing service models of community mental health practice. Psychiatric Services 51:656–658, 2000Link, Google Scholar

11. Fiander M, Burns T, McHugo GJ, et al: Assertive community treatment across the Atlantic: comparison of model fidelity in the UK and USA. British Journal of Psychiatry 182:248–254, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Tighe J, Henderson C, Thornicroft G: Mentally disordered offenders and models of community care provision, in Care of the Mentally Disordered Offender in the Community. Edited by Buchanan A. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 2002Google Scholar

13. Williams PL, Webb C: The Delphi technique: an adaptive research tool. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 61:153–156, 1994Google Scholar

14. Linstone HA, Turoff M: The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Reading, Mass, Addison-Wesley, 1975Google Scholar

15. Jones J, Hunter D: Consensus methods for medical and health services research. British Medical Journal 311:376–380, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Fiander M, Burns T: Essential components of schizophrenia care: a Delphi approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 98:400–405, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Slade M, Powell R, Rosen A, et al: Threshold Assessment Grid (TAG): the development of a valid and brief scale to assess the severity of mental illness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:78–85, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H: Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32:1008–1015, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

19. Ogloff JR, Roesch R, Eaves D: International perspective on forensic mental health systems. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 23:429–431, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Judge J, Fahy T: Survey of community forensic psychiatry services in England and Wales. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology 15:244–253, 2004Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Whittle M, Scally M: Model of forensic psychiatric community care. Psychiatric Bulletin 22:748–750, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar