Lessons Learned About the Chronic Mentally Ill Since 1955

INTRODUCTION

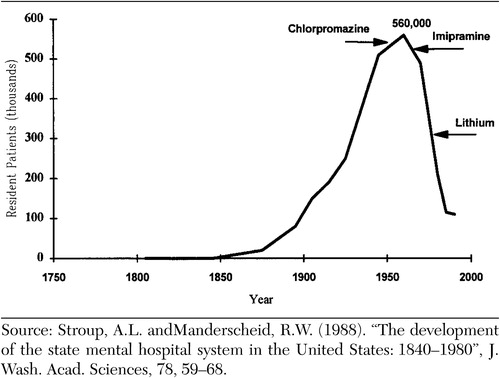

I have chosen 1955 for two obvious reasons. First, it was the year in which the population housed in state and county psychiatric hospitals across the United States reached its height of almost 560,000 (Stroup and Manderscheid, 1988). Second, it was the year during which chlorpromazine was introduced into the formularies of most state hospital systems (Ayd, 1970). Since then, almost 40 years of deinstitutionalization has reduced this population to about 100,000 individuals during which period we have seen the continuing introduction of new pharmacological agents, including imipramine and lithium (see Table 1).

My choice of starting this analysis in 1955 does not imply that nothing of consequence occurred regarding care and treatment of the chronic mentally prior to that date. Indeed, several critical developments were present that directly led to the current situation (Talbott, 1982; Talbott, 1983).

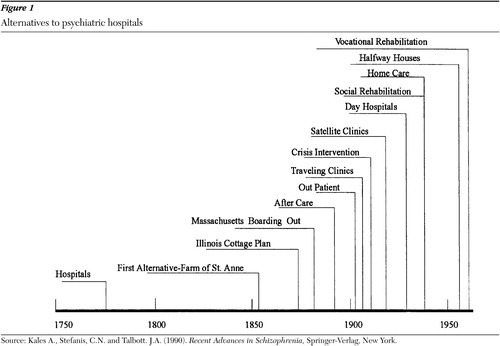

First, while the nation's first public psychiatric hospital, the "Publick Hospital" in Williamsburg, Virginia, was opened in 1773, and state mental hospitals blossomed in the nineteenth century, there were a host of "alternatives" to hospitals established in the United States beginning in 1855. The first of these was the Farm of St Anne in Illinois, followed by cottage plans and boarding out programs; aftercare, outpatient services, traveling and satellite clinics; crisis intervention programs; day hospitals, home care and halfway houses; and social and vocational rehabilitation. Indeed, by 1955, we had in place most of what we would now consider essential to the establishment of a community mental health or community system of care; albeit not available in sufficient numbers or widely enough (see Figure 1).

Second, in 1946, following World War II, the United States Congress enacted our first national Mental Health Act. This was prompted by the experience during the war of discovering that many inductees suffered from previously undetected mental illnesses and the public's shock at learning that during one month, more draftees were discharged for "medical reasons" than inducted; coupled with the horrible conditions in state psychiatric hospitals encountered by conscientious objectors performing alternate service there; plus a wish to upgrade the small federal "Division of Mental Hygiene" to a National Institute comparable to other parts of the National Institute of Health. This act stimulated research, demonstration projects, training and assistance to states. More important, though, it set in motion a process that resulted in a report from a "blue ribbon" Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health entitled "Action For Mental Health," that called for an altered role for the large state hospitals, that in turn resulted in the community mental health center (CMHC) legislation of 1965, led by then-President John F. Kennedy.

Third, there was a sea change in American psychiatry concerning the philosophy in care and treatment of the mentally ill. This was prompted in part by the visit of a dozen or so leaders in American psychiatry to the UK in 1954 where they were profoundly impressed by the prevailing philosophy that regarded persons with psychiatric disorders like those with medical or surgical disorders. They also were impressed with innovations such as the "open door" and the "therapeutic milieu". Some of the same experts had also participated on a committee of the World Health Organization (WHO), that drafted a document during this same decade spelling out exactly what elements constituted what they termed a "community hospital"; e.g., outpatient services, partial hospitalization, community education, rehabilitation and research.

In 1954, New York State passed the first state Community Mental Center Services Act. The ingredients specified in this landmark legislation were: inpatient and outpatient services, consultation and education, and rehabilitation. Thus, by 1955, by adding together the different elements specified by New York State and WHO, the outlines emerged of the 1963 Kennedy CMHC bill (with the addition of 24-hour emergency care, diagnostic services, precare and aftercare). It is of note that the CMHC Amendments of 1975 were enacted to "pick-up" many of the pieces left in the wake of deinstitutionalization; e.g., screening mentally ill persons in the courts and community agencies prior to admission to state hospitals, follow-up care, and transitional housing as well as services for under-served populations such as persons suffering from alcoholism, drug abuse, children and the elderly.

The Survey

In order to ascertain what experiences and research since 1955 could shed light on what we have learned about the care and treatment of the mentally ill since deinstitutionalization began in 1955, I undertook a survey of over 20 experts in the field of chronic mental illness. This is a totally unscientific sample, consisting primarily of those doing research and writing on the subject, but includes most of the prominent names associated with the field. After receiving their answers to a broad request for developments in research and experience, I clustered them in groupings and had the experts rank-order them. What I will present in the remainder of the chapter represents the top ten areas, grouped under three headings: (I) Illness, (II) Treatment and (III) Programs. For each of the ten sub-areas, I have selected one or more important studies, which I will summarize, drawing from each a Lesson Learned. At the end of this presentation, I will try to tie these ten lessons together.

The three broad categories and ten sub-areas are:

I.Illness

1.Course

2.Relapse

3.Length Of Stay

II.Treatment

4.Therapy

5.Behavior Modification

6.Therapeutic Interaction

7.Rehabilitation

III.Programs

8.Community

9.Alternatives

10.Continuity of Care

Before starting, I think it is important to state that I utilized Leona Bachrach's (1976) definition of persons suffering from mental illness as "those individuals who are, have been, or might have been, but for the deinstitutionalization movement, on the rolls of long-term mental institutions, especially state hospitals".

I. Illness

1. Course of illness. Prior to 1955, we had very little data on the courses of illness followed by persons suffering from chronic mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and little idea of their ultimate outcome. Now, however, we have a much better idea (see Tables 2 and 3).

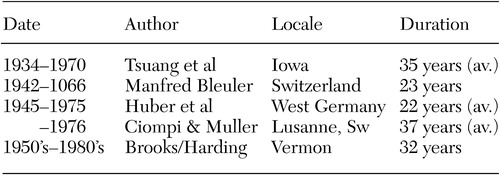

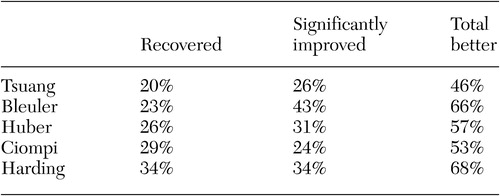

The first five studies published on the long term outcome of persons suffering from schizophrenia followed patients from 22 to 37 years, most starting long before the introduction of antipsychotic medications. They demonstrate strikingly similar results (Tsuang 1979, Bleuler 1968, Huber 1980, Ciompi 1980, Harding 1987). This is surprising, since the studies were conducted in two European countries and two American states.

At a minimum, 20% of patients recover (with a range of 20-34%), at least 24% show significant improvement (range 24-43%) leading to a total percentage who are better off at follow-up at a minimum of 46% (range 46-68%).

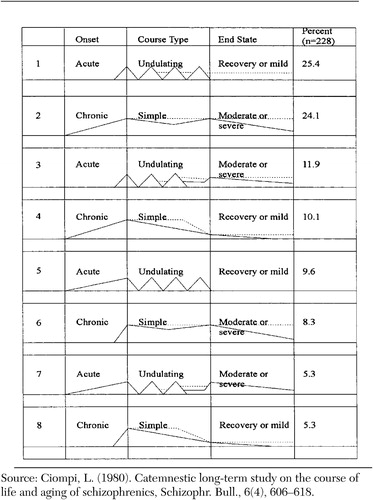

We also understand much more today than we did in 1955 about the courses of illness of persons suffering from schizophrenia. Luc Ciompi (1980) identified eight different patterns; dividing them by onset (acute or chronic), course (simple or episodic) and end state (recovery/mild or moderate/severe). The largest group, constituting a quarter of the sample, had acute onsets, undulating courses and rather good outcomes. Almost the same number, however, had chronic onsets, simple (deteriorating) courses and poor outcomes (see Table 4).

What then can we learn from these long-term follow-up studies? First, that despite often stormy, dehabilitating and even deteriorating courses of severe illness, some individuals suffering from schizophrenia wind up rather alright. Second, that different persons have differing onsets, courses and outcomes.

As a result, any system of care for persons suffering from schizophrenia must not be unifocal; that is, it cannot focus only on hospital treatment or only on community care. Instead, it must accommodate persons who have sudden onsets of illness (e.g., with emergency and crisis services), chronic onsets (e.g., with monitoring and periodic reassessment); undulating courses (e.g., with acute crisis, hospital and outpatient services), simple courses (outpatient, partial hospital, supervised housing, community care teams, residential care, case management, etc.); poorer outcomes (ongoing long-term care) and better outcomes. The lesson to be learned here then, is that: Lesson #1: Different Strokes For Different Folks.

2. Relapse. Relapse in persons suffering from schizophrenia and other chronic illnesses is another area in which we had little data prior to 1955. Now, due to the work of several investigators, however, we know much more than we did then.

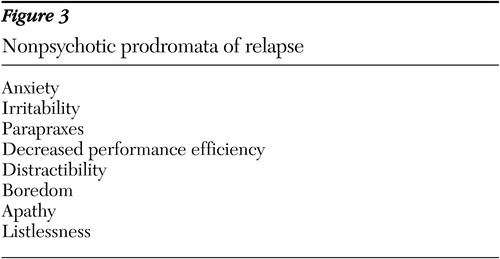

Hogarty (1979) has established that even on medication, over 40% of persons suffering from schizophrenia will relapse in one year. In addition, Docherty (1978) and Herz (12) have identified non-psychotic prodromata of relapse; symptoms such as anxiety, irritability, parapraxes, decreased performance efficiency, distractibility, boredom, apathy and listlessness (see Figure 3).

This identification of such common symptoms has led to fruitful research on "low dose" and "no-dose" strategies (Marder 1987, Carpenter 1987). In addition, recognition of these common indicators of relapse, coupled with individual patients' own typical pre-psychotic behaviors such as calling the police, staying up all night, etc., enables clinicians to utilize low dose or no dose strategies, moving in with medication only when individuals are at risk for exacerbations in their illnesses.

Thus, we can conclude from these studies that while we are dealing with a difficult, often-relapsing illness (40% in a year), we can predict relapse in some patients and refine our treatment approaches. The lesson to be learned here then is that: Lesson #2: Relapse Makes Some Sense.

3. Length of inpatient hospital stays. Since 1955, several critical analyses of lengths of inpatient hospital stays have been published (Glick 1979, Herz 1976, Mattes 1982). A major problem with studies on lengths of stay is that they have dropped dramatically since 1955; thus the standard of what is "short" vs what is "long" has changed (shortened) each year. For example, the study with the longest length of stay defines "short" as under 90 days and "long" as 179 days; the study with the shortest length of stay defines "short" as 8 days and "long" as 24 days.

Nonetheless, the results show a consistent pattern; that long-term hospitalization does not add anything for those suffering from chronic mental illnesses. It was previously believed that persons suffering from chronic illnesses required longer admissions and those suffering their first breaks, short stays (Talbott and Glick 1986). Now, however, we must conclude that persons coming in for their 12th or 13th hospitalization do better with a rapid reevaluation, re-equilibration on medication and revision of the treatment plan, followed by discharge to a community program, and those having their first break, deserve a complete and thorough psychiatric, social and neuropsychological evaluation. The lesson here then, is that: Lesson #3: More Is Not Better.

II. Treatment

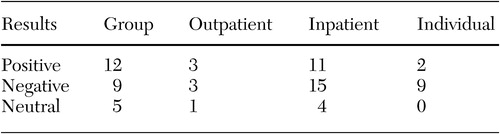

4. Therapy. Several persons (May and Simpson 1980, Luborsky 1975, and Mosher and Keith 1979) have been concerned with the few studies (for example, Herz 1974) that compare individual versus group therapy with persons suffering from schizophrenia. The two commonest methods of comparison use box scores or meta-analyses. I have attempted to summarize May and Simpson's careful analysis of these studies in Table 5.

There are more studies showing a positive than negative result from group treatment and more showing the superiority of therapy in outpatient settings. May and Simpson conclude that "with schizophrenics, group therapy is more successful with outpatients after discharge than is group or individual therapy with inpatients. In addition, Luborsky notes that one specific study (O'Brien 1972) clearly "showed an advantage for treatment."

Therefore, contrary to the prevailing belief of patients, families, psychiatrists and even third-party reimbursers, group therapy would appear from the data to have the edge over individual treatment. The lesson then, is that: Lesson #4: Group Therapy is the Preferred Treatment, especially when conducted in outpatient settings.

5. Behavior Modification. Gordon Paul (1969) reviewed the research on treatment approaches for persons suffering from chronic mental illnesses and concluded that two showed special promise; these were behavioral methods and milieu treatment. He then studied the outcomes of these two approaches versus controls in a state hospital population in Illinois. The results (Paul and Lentz 1977) were quite dramatic. All patients were randomly assigned to inpatient hospital treatment that consisted of one of three treatment programs: a behavioral approach emphasizing resocialization and social relearning techniques; milieu therapy; or "traditional state hospital treatment," which essentially consisted of medication and large group meetings. After discharge, all were followed with traditional aftercare, that is, the behavioral or milieu approaches were discontinued.

At 18 months, 92.5% in the Social Learning Program and 71% who had been exposed to the Milieu Program were still in the community, versus only 48.4% of the Controls. It is ironic, therefore, to note the absence of structured behavioral programs in psychiatric hospitals today, versus their popularity 20 years ago, despite such obvious success. Granted, lengths of stays have fallen, graduate psychology programs are now more interested in other areas, and many ward programs incorporate behavioral methods as "routine standard care," but their current absence cannot be attributed to lack of efficacy. My lesson here, therefore, is that: Lesson #5: Behavior Therapy Is Effective.

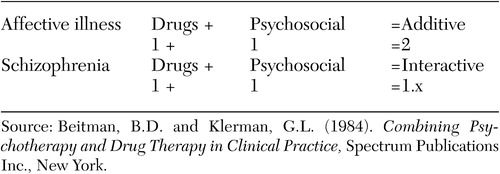

6. Therapeutic Interaction. For a number of years there has been growing evidence for the increased efficacy of combinations of treatment interventions (see Table 6). Philip May (1968) compared the effectiveness of "ataraxic" medication, individual psychotherapy, milieu treatment and ECT alone and the combination of "ataraxic" medication and individual psychotherapy. He found that the worst outcomes were in two "alones": psychotherapy or milieu; and that while the combination was better, it was not statistically significantly better than drugs alone.

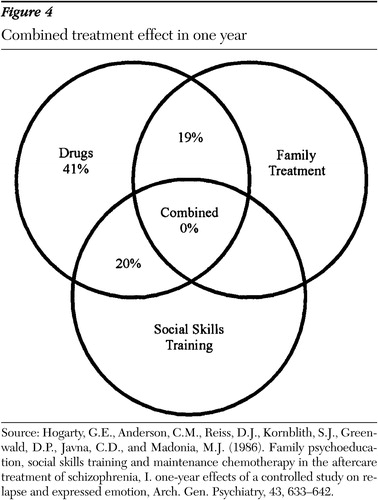

Beitman and Klennan (1984), however, saw a definite effect; they concluded that with affective illness the two interventions were additive (that is, 1 + 1 = 2), whereas with schizophrenia they were interactive (that is 1 + 1 might equal 1.3 or 1.4). More recently, Gerald Hogarty (1986) demonstrated that (as stated previously) about 40% of persons suffering from schizophrenia experienced relapses in one year, even on medication; but the addition of either social skills training or family treatment cut that in half (to about 20%) and the provision of all three resulted in no relapses. This powerful effect erodes over time, but its initial impact is impressive (see Figure 4).

The inevitable conclusion that I draw, then, from examination of these studies is that not only does treatment make a significant difference in persons suffering from schizophrenia, in combination it makes a very sizeable difference. Thus the lesson here, is that: Lesson #6: More is Better.

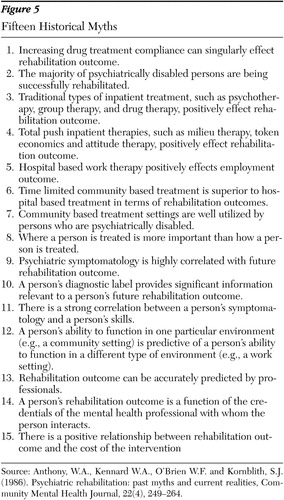

7. Rehabilitation. The field of psychiatric rehabilitation, like that of physical rehabilitation, almost did not exist in 1955. Since then, however, we have seen the steady growth of research, experience and expertise. To summarize all we have learned in the recent past from the research in psychiatric rehabilitation, William Anthony (1986) has expostulated a list of "myths" (see Figure 5).

Another innovator in the field John Stares, followed several patients for extended periods of time and concluded that there was no one single index of disability, instead there were several indices, including work, social skills, symptomatology and general; all of which were independent of the others (Stares 1978, 1984). While clinically we have suspected that persons can have a great deal of symptomatology but little disability and vice-versa, it is useful to know this definitively. Because someone cannot function in one place, does not mean he or she cannot function in another.

Finally, Robert Liberman and colleagues (1980, 1982, 1984, 1986a, 1986b, 1987) have pioneered in the development of rehabilitation training modules that can be easily understood, learned and communicated among professionals in the field. These are available in written and video formats and use very practical methods of improving social skills, such as Behavioral Rehearsal, Prompting, Modeling, Reinforcement, Shaping, In-vivo Exercises, and Homework. The modules include such areas as Conversation Skills, Personal Effectiveness, Social Problem-solving, Personal Finances, Grooming, Vocational Preparedness, Medication Management, and Recreation for Leisure.

Thus, I conclude from all these efforts that if patients have a disability in addition to a disease, they require both treatment and rehabilitation and that we now possess the knowledge as to how to effectively deliver rehabilitation. The lesson here, then, is that: Lesson #7: Treatment Alone Is Not Enough.

III. Programs

8. Community Programs. Fountain House, which was founded shortly following World War II, pioneered in providing a community based program that offered what I term the psycho-social triad of housing, vocational rehabilitation and social rehabilitation. Studies have shown that outcomes for participants in this innovative program were strikingly better than those of controls (Beard 1978). Whereas 17% of Fountain House members were readmitted 6 months after discharge from the hospital, only 37% of controls were.

Leonard Stein and Mary Ann Test studied a group of patients randomly assigned to an assertive community treatment approach that provided individualized treatment and care from a comprehensive array of services (Stein and Test 1980, Test and Stein 1980). Their results showed that patients receiving this targeted approach showed subsequently lower rehospitalization and symptomatology and significantly increased employment, satisfaction and time spent with trusted friends.

The economic results (Wiesbrod, Stein and Test 1980), however, revealed a problem many community programs face. For while the overall impact was a reduction in estimated total costs of 6% per patient, the costs of delivering these decentralized, individualized services was 11% more, offset, however, by increased benefits of 16%. Thus, if the cost side of personnel, etc., is financed by mental health resources, and the benefits accrued because of decreased police costs and family burden as well as increased tax revenues, etc., the mental health authorities and legislators do not see the investment paid back into the same account it was spent from.

With all the caveats about making generalizations about a diverse population, then, the lesson to be learned from this research is that: Lesson #8: Community Treatment Is Better.

9. Alternatives to Hospitals. As mentioned above and as displayed in Illustration 2, we have seen the innovation of and expansion in alternatives to hospitals for over a century. What is the scientific evidence of their efficacy or lack of it? [Note: Figure 2 is missing from the Wiley original.]

Interestingly, a decade ago two meta-analyses of various alternative treatment programs were published in the United States within months of each other (Braun 1981, Kiesler 1982). Their conclusions were astoundingly similar. Braun et al concluded that "experimental alternatives have led to psychiatric outcomes not different from and occasionally superior to those of patients in control groups." Kiesler stated that "In no case were the outcomes of hospitalization more positive than alternative treatment." These conclusions have led to the development of even more alternatives, such as the Inn at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center (Gudeman 1983). Here, again, the lesson seems clear, that: Lesson #9: Alternatives To Hospitals Are Better.

10. Continuity of Care. The final area in my survey results, deals with what may be the most important issue of all when it comes to discussing treatment and care of individuals suffering from chronic mental illnesses; continuity of care. In looking at the entire body of research on what seems most effective in preventing or forestalling exacerbations of illness or rehospitalization, two items appear again and again; continuance on medication and continuance in some form of aftercare or outpatient program; both of which are so dependent on continuity of care. It is therefore not only discouraging to learn (Minkoff 1978) that fewer than 25% of persons continue to be seen in programs following discharge and fewer than 50% continue their prescribed medication but to realize that continuity of care is actually practiced so seldom with this population.

Confirmation of the importance of longitudinal involvement comes for the Veterans Administration's Cooperative Day Hospital Study (Linn 1979) that concluded that "high patient turnover and brief but more intensive treatment...may lead to relapse."

My reading of all these results indicates to me that the lesson to be learned here is that, no matter how good the treatment, rehabilitation and care is, if patients are not involved on an on-going basis, it hardly matters. So I conclude that: Lesson #10: Continuity of Care Is Critical.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

In this survey of what of significance has occurred regarding the chronic mentally ill since 1955, I do not want to give the impression that these ten areas are the only areas of importance. Certainly, we have experienced an explosion in the areas of basic science (e.g., genetics) and neuroscience (e.g., neurotransmitters) as well as more clinically-related research in areas such as epidemiology and imaging. In addition, the growth of the family movement has been an enormous help in the advocacy for research in and services for the chronic mentally ill in the United States. Unfortunately, during this 40 year period, another force has been that of the legal advocates, who have sponsored initiatives (such as the right to refuse treatment, attempts to end involuntary commitment, etc.) that have been well-intentioned but naive and have bedeviled our ability to provide service advocacy for afflicted patients.

Ironically, though, it is probably neither science nor advocacy that has shaped and will continue to shape services for the seriously mentally ill, but the economic forces psychiatry and all of medicine in the United States are currently facing. Just as services have been profoundly influenced in the recent past by cost-cutting and cost-controlling initiatives such as: prospective pricing, utilizing diagnostic related groups (DRG's); health maintenance organizations (HMO's); and managed care, future directions are certain to be directed by whatever shape the final American national health care reform takes.

As a footnote, it is disappointing to note that despite the federal government's vigorous efforts to promote CMHC's in the 1960's and 1970's to help states and localities share the burden of community care of the mentally ill, except for the inadequately-funded Community Support Program and the McKinney Program for the Homeless, federal leadership has been lacking.

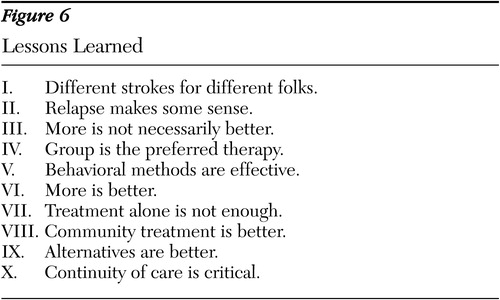

What are the bigger lessons to be learned from my list of ten lessons (see Figure 6)? At first blush it would appear that some lessons are contradictory; e.g., more is not better when it refers to inpatient hospitalization but more is better when it refers to modalities delivered in the community. However, I think that there are certain themes that do emerge from these ten lessons.

First, multiple treatments and rehabilitation seem to provide better outcomes. Second, continuity of care seems to be critical. And third, comprehensive care must be provided.

None of these principles is new. But, we have yet to implement what our research findings demonstrate. To accomplish that, several things must be done. First, we must bring about changes in the system or non-system of care we have, addressing not merely the problems of individual patients but the "system" of care for them. Second, we must pay attention to policy issues, shaping it rather than letting it shape us. And third, we must perform more health services experiments such as (1) those sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which is looking into making services for the chronic mentally ill work better in our large cities, (2) those stemming from the Institute of Medicine's study comparing generic services for the chronic mentally ill, frail elderly and mentally retarded over the age of 21, and (3) those that attempt to assess the clinical and fiscal impact of new funding and administrative efforts, such as capitation, etc.

The biggest lesson to be learned, however, from our almost 40 year old experiment with deinstitutionalization, is that we simply have not learned our lessons. While waiting for science to bring us a definitive answer regarding the causation and treatment of those suffering from chronic mental illness, we must still act. If we truly want to address the problems posed by this difficult population, we must first begin by implementing what we know and do it now.

This article was originally published in Schizophrenia: Exploring the Spectrum of Psychosis, edited by R. J. Ancill, S. Holliday, and J. Higenbottam, pages 1-20, 1994, Wiley & Sons, London. Reproduced by permission of John Wiley & Sons Limited.

Figure 1. Alternatives to psychiatric hospitals

Figure 3. Nonpsychotic prodromata of relapse

Figure 4. Combined treatment effect in one year

Figure 5. Fifteen Historical Myths

Figure 6. Lessons Learned

|

Table 1. The population in state and county hospitals

|

Table 2. Long term follow up studies

|

Table 3. Long term outcome

|

Table 4. Course of illness for persons with schizophrenia

|

Table 5. Studies comparing the superiority of treatment in inpatient vs. outpatient settings, group vs. individual treatment

|

Table 6. Drug/psychosocial interaction

Anthony, W.A., Kennard, W.A., O'Brien, W.F. and Kornblith, S.J. (1986). "Psychiatric rehabilitation: past myths and current realities", Comm. Ment. Health J., 22(4), 249–264.Google Scholar

Ayd, F.J. (1970). Discoveries in Biological Psychiatry, Philadelphia, Lippincott, Philadelphia.Google Scholar

Bachrach, L.L. (1976). "Deinstitutionalization: an analytical review and sociological perspective", NIMH, Rockville, MD.Google Scholar

Beard, J.H., Malamud, T.J., and Rossman, E. (1978). "Psychiatric rehabilitation and long-term rehospitalization rates: the findings of two research studies" Schizophr. Bull. 4(4), 622–635.Google Scholar

Beitman, B.D. and Klerman, G.L. (1984). Combinination Psychotherapy and Drug Therapy in Clinical Practice, Spectrum Publications, Inc., New York.Google Scholar

Bleuler, M. (1969). "A 23-year longitudinal study of 208 schizophrenics and impressions in regard to the nature of schizophrenia". In The Transmission of Schizophrenia (eds. E. Rosenthal and S.S. Ketty), Pergamon, Oxford.Google Scholar

Braun. P., Kochansky W G., Shapiro, R., Greenberg, S., Gudeman, J.E., Johnson, S. and Shore, M.F. (1981). "Overview: deinstitutionalization of psychiatric patients, a critical review of outcome studies", Am. J. Psychiatry, 138(6), 736–749.Google Scholar

Carpenter, W.T., Heinrichs, D.W. and Hanlon, T.E. (1987). "A comparative trial of strategies in schizophrenia", Am. J. Psychiatry 144, 1466–1470.Google Scholar

Ciompi, L. (1980). "Catamnestic long-term study on the course of life and aging of schizophrenics", Schizophr. Bull, 6(4), 606–618.Google Scholar

Docherty, J.P., Van Kammen D.P., Siris, S.G. and Marder, S.R. (1978) "Stages of onset of schizophrenic psychosis", Am. J. Psychiatry, 135(4) 420–426.Google Scholar

Glick, I.D. and Hargreaves, W.A. (1979). Psychiatric Hospital Treatment for the 1980's, Lexington Books, Lexington, MA.Google Scholar

Gudeman, J.E., "Shore, hospitalization and an inn instead of inpatient care for psychiatric patients", The New Engl. J. of Med., 308(13), 749–753.Google Scholar

Harding, C.M., Zubin, J. and Strauss, J.S. (1987). "Chronicity in schizophrenia: fact, partial fact or artifact?", Hosp. Comm. Psychiatry, 38(5), 477–486.Google Scholar

Herz, M.I. (1984). "Recognizing and preventing relapse in patients with schizophrenia", Hosp. Comm. Psychiatry, 35(4), 344–349.Google Scholar

Herz, M.I., Endicott, J. and Spitzer, R.L. (1976). "Brief vs. standard hospitalization: the families", Am. J. Psychiatry, 133,795–801.Google Scholar

Herz, M.I., Spitzer, R.L., Gibbon, M., Greenspan, K. and Reibel, S. (1974). "Individual vs. group aftercare treatment", Am. J. Psychiatry, 131(7), 808–812.Google Scholar

Hogarty, G.E., Anderson, C.M., Reiss, D.J., Kornblith, S.J., Greenwald, D.P., Javna, C.D. and Madonia, M.J. (1986). "Family psychoeducation, social skills training and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia, I. one year effects of a controlled study on relapse and expressed emotion", Arch. Gen. Psychiat, 43, 633–642.Google Scholar

Hogarty, G.E., Schooler, N.R., Ulrich, R., Mussare F. and Ferro, P. (1979). "Fluphenazine and social therapy in the aftercare of schizophrenic patients", Arch. Gen. Psychiat, 36, 1283–1294.Google Scholar

Huber, G., Gross, G., Schuttler, R. and Linz, M. (1980). "Longitudinal studies of schizophrenic patients", Schizophr. Bull, 6(4), 592–605.Google Scholar

Kales, A., Stefanis, C.N. and Talbott, J.A. (1990). Recent Advances in Schizophrenia, Springer-Verlag, New York.Google Scholar

Kiesler, C.A. (1982). "Mental hospitals and alternative care, noninstitutionalization as potential public policy for mental patients", Am. Psychologist 37(4), 349–360.Google Scholar

Liberman, R.P. (1982). "Assessment of social skills", Schizophr. Bull, 8(1), 62–84.Google Scholar

Liberman, R.P., Falloon, I.R.H., and Wallace, C.J. (1984). "Drug-psychosocial interactions in the treatment of schizophrenia", in The Chronically Mentally Ill: Research and Services (Ed. M. Mirabi) Spectrum Publications, Inc., New York.Google Scholar

Liberman, R.P. "Psychiatric rehabilitation of schizophrenia: editor's introduction", Schizophr. Bull, 12(4), 540–541.Google Scholar

Liberman, R.P., Mueser, K.T., Wallace, C.J., Jacobs, H.E., Eckman, T. and Massel, H.K. "Training skills in the psychiatrically disabled: learning coping and competence", Schizophr. Bull, 12(4), 631–647.Google Scholar

Liberman, R.P. (1987). "Skills training for community adaptation of chronic mental patients", Comm. Psychiatrist, 2(3), 5–17.Google Scholar

Linn, M.W., Caffey, E.M., Klett, C.J., Hogarty, G.E. and Lamb, R. (1979). "Day treatment and psychotropic drugs in the aftercare of schizophrenic patients," Arch Gen Psychiatry, 36, 1055–1066.Google Scholar

Luborsky, L., Barton, S. and Luborsky, L. "Comparative Studies of Psychotherapies: is it true that "everyone has won and all must have prizes?" Arch Gen. Psychiatry, 32, 995–1008.Google Scholar

Marder, S.R., Van Putten T., Mintz, J., Lebell, M., McKenzie, J. and May, P.R. (1987). "Low-and conventional-dose maintenance therapy with fluphenazine decanoate, two year outcome", Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 44, 518–521.Google Scholar

Mattes, J.A. (1982). "The optimal length of hospitalization for psychiatric patients: a review of the literature", Hosp. Comm. Psychiatry, 33(10), 824–828.Google Scholar

May, P.R.A. (1968). Treatment of Schizophrenia. A Comparative Study of Five Treatment Methods, Science House, New York. May, P.R.A. and Simpson G.M. (1980). Schizophrenia: evaluation of treatment methods. In Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 3rd Edition (eds. H.I. Kaplan, K.M. Freedman and B.J. Sadock), APPI, BaltimoreGoogle Scholar

Minkoff, K. (1978). "Map of the chronic mental patient". In The Chronic Mental Patient (ed. J.A. Talbott), APA, Washington, DC.Google Scholar

Mosher, L.R. and Keith, S.J. (1979). "Research on the psychosocial treatment of schizophrenia: a summary report", Am. J. Psychiatry, 136(5),623–631.Google Scholar

O'Brien C., Hamm, K., Ray, B., et al (1972). "Group vs individual psychotherapy with schizophrenics: a controlled outcome study", Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 27, 474–478.Google Scholar

Paul, G.L. (1969). "Chronic mental patient: current status-future directions", Psycho. Bull 71, 81–94.Google Scholar

Paul, G.L. and Lentz, R.J. (1977). Psychosocial Treatment of Chronic Mental Patients, University Press, Cambridge, MA.Google Scholar

Stein, L.I. and Test, M.A. (1980). "Alternative of mental hospital treatment, I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation", Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 37, 392–397.Google Scholar

Strauss, J.S. (1984). "Assessment of treatment in outpatient settings". In The Chronically Mentally Ill: Research and Services (ed. M. Mirabi), Spectrum Publications, Inc., New York.Google Scholar

Strauss, J.S. and Carpenter, W.T., Jr. (1978). "The prognosis of schizophrenia: rationale for a multidimensional concept", Schizophr. Bull. 4(1), 56–67.Google Scholar

Stroup, A.L. and Manderscheid, R.W. (1988). "The development of the state mental hospital system in the United States", 1840–1980, J. Wash. Acad. Sciences, 78, 59–68.Google Scholar

Talbott, J.A. (1982). "Twentieth-century developments in American Psychiatry", Psych Quarterly, 54(4), 207–219.Google Scholar

Talbott, J.A. and Kaplan, S.R. (1983). Psychiatric Administration: A Comprehensive Text for the Clinician-Executive, Grune & Stratton, Orlando FL.Google Scholar

Talbott, J.A. (1983). "Trends in the delivery of psychiatric services". In Psychiatric Administration (eds. J.A. Talbott and S.R. Kaplan), Grune & Stratton, New York.Google Scholar

Talbott, J.A. and Glick, I.D. (1986). "The inpatient care of the chronically mentally ill", Schizophr. Bull., 12(1), 129–140.Google Scholar

Test, M.A. and Stein, L.I. (1980). "Alternative to mental hospital treatment, III. social cost", Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 37, 409–412.Google Scholar

Tsuang, M., Woolson, R. and Fleming, J. (1979). "Long-term outcome of major psychoses, I: schizophrenia and affective disorders compared with psychiatrically symptom-free surgical conditions", Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 36, 1295–1301.Google Scholar

Wallace, C.J., Nelson, C.J., Liberman, R.P., Aitchison, R.A., Lukoff, D., Elder, J.P. and Ferris, C. (1980). "A review and critique of social skills training with schizophrenic patients", Schizophr. Bull, 6(1), 42–63.Google Scholar

Weisbrod, B.A., Test, M.A. and Stein, L.I. (1980). "Alternative to mental hospital treatment, economic benefit-cost analysis", Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 37, 400–405.Google Scholar