Back to the Future: Funding, Integrating, and Improving Mental Health Services

The three jeremiads reprinted here, written by John Talbott in the early 1980s, bring to mind Yogi Berra's memorable comment, "It's deja vu all over again." The sense of injustice, disaster, frustration, and outrage articulated by John Talbott as he assumed the presidency of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in 1985—as well as his forward-looking resolve—could have been voiced, in almost the same words, by any of his most recent successors. How could things have changed so little in 20 years? Has there been no progress? Five themes resound with contemporary echoes from Talbott's historical podium.

The first is homelessness. In 1983, Talbott railed against the tragedies in cities such as New York, where 36,000 homeless people lived on the streets and in shelters, many with severe mental illness. Twenty years later the Web site of the New York City Department of Homeless Services reports that there are almost 38,000 homeless New Yorkers, even though the city now spends $641 million annually on homeless services and has made a remarkable investment of $5 billion to build 250,000 units of low-income housing (1).

The second theme is funding. In his 1984 remarks to the APA, Talbott catalogued the then-new cost-containment mechanisms and governmentwide funding cutbacks that were seriously jeopardizing services for people with mental illness. Almost 20 years later, Paul Appelbaum spent much of his APA presidency drawing attention to the continuing meltdown in public mental health systems in Massachusetts and elsewhere (2).

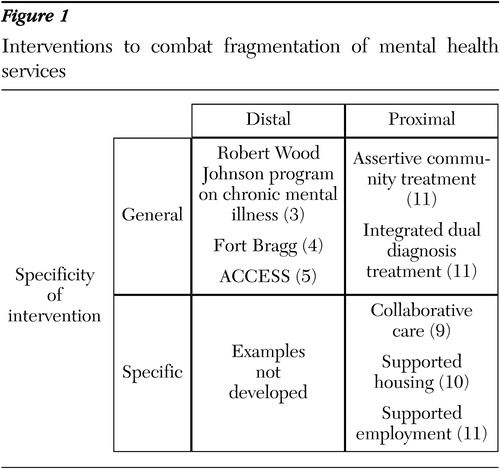

The third theme is systems integration. In his 1985 review of public psychiatry, Talbott decried the "fragmentation of the psychiatric delivery nonsystem" and pleaded for the development of "a unified systems approach." In the following decades, hundreds of millions of dollars were spent on three large service demonstration projects that tested systematic solutions to this problem, but none found evidence that such systemwide integration efforts yielded clinical benefits (3,4,5). Last year, the transmittal letter of the final report of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health echoed Talbott's claims, "for too many Americans with mental illnesses, the mental health services and supports they need remain fragmented, disconnected, and often inadequate." But the Commission did not recommend global, top-down approaches to the problem. Rather, it focused on the need for recovery-oriented services at the client level, echoing Talbott's exhortations that policy and practice be guided by a "focus on the patient."

The fourth theme is research. In addressing each issue, Talbott pinned his hopes on progress in research. He urged advocates not to forget the fundamental importance of research on epidemiology, basic mechanisms of disease, and treatment effectiveness. And when it came to funding schemes or integrative administrative mechanisms, he espoused no single approach but rather urged that diverse approaches be studied and that the field be guided by results.

The fifth theme is advocacy. Recognizing that reason and right do not make policy, Talbott called on his colleagues and on the families of people with mental illness to become advocates. Since that time, the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill has become an ever more powerful public voice. The New Freedom Commission was established in no small part because of the advocacy efforts of Senator Pete Domenici of New Mexico, who has been courageously public, over many years, about his daughter's struggle with schizophrenia. Every year more celebrities, from Tipper Gore to Rush Limbaugh, disclose their experiences with mental illness. Sadly, however, stigma remains strong.

Although almost all the challenges Talbott targeted are still with us, we have made some progress with some of them, although not as much as he—and we—would like. Although 20 years may be a long time in one person's career, it is a far shorter time for effecting major social change.

There are two reasons for looking back at the work of a revered teacher and professional leader. The first is aesthetic—to rediscover the clarity of that person's thinking and the passion and comprehensiveness of his vision, and to repay those gifts with honor. The second is more pragmatic—to get a clearer fix on where we stand today.

There are at least two recent developments that John Talbott did not anticipate but that fit well within the broad frame of his concerns: the advent of atypical antipsychotic medications and the development of the evidence-based practice approach to quality improvement.

The publication, in 1988, of a landmark clinical trial showed clozapine to be superior to haloperidol in the treatment of treatment-refractory schizophrenia (6), and the arrival of the safer second-generation agents—risperidone in 1994 and olanzapine in 1996—led to the rapid dissemination of these agents so that they are now prescribed to more than 70 percent of all patients with schizophrenia. Annual reports from the manufacturers of these medications suggest total annual sales of $8.7 billion in 2003, enough money to pay the salaries of 1.5 million case managers or rehabilitation specialists who could provide intensive community-based services to some 15 million consumers.

Some recent studies have questioned the magnitude of the benefits of these medications, even for side effects (7), and reports of serious metabolic consequences (8) leave it unclear whether these benefits are equal to those that would result from a similarly massive investment in evidence-based community services that are available to distressingly few patients. The ready availability of increased funding for a modest improvement in pharmacologic effectiveness stands in marked contrast to the continuing crisis in the availability of psychosocial treatment and adds an ironic wrinkle to the Talbott-Appelbaum concern with declining funding. Institutional constraints often determine public policy as much as rational choice does, and the past two decades have looked far more kindly on private-sector expansions—even when they are largely funded with public Medicaid dollars—than on the development of services that are regarded as expansions of the governmental sector.

In terms of evidence-based practices, although large-scale demonstration projects failed to show that consumers gained from overarching efforts at system integration (3,4,5), a new approach to quality improvement has emerged that focuses more directly on clinical practice. Many studies have shown that systematically structured collaborations, implemented proximal to patients, can improve outcomes in ways that did not appear with large-scale organizational interventions (9,10). A monthly series of articles published in Psychiatric Services in 2001 summarized outcome data for six psychosocial interventions, including assertive community treatment, supported employment, and family psychoeducation (11). In principle, these interventions have been shown through multiple clinical trials to improve client outcomes, and the fidelity of their implementation can be monitored to ensure that effective practices are being used. The advantages of this approach are that interventions are delivered proximal to patients rather at distal organizational levels and that in some cases (but not all) they are based on specific, operationally defined activities that can be taught and monitored in routine practice rather than being based on abstract organizational developments. This shift from a focus on distal and general interventions to proximal but specific interventions progressively embodies the "focus on the patient" that Talbott placed at the center of his APA presidency and that seems to have been rediscovered in other areas of medical care and renamed "patient-centeredness" (12) (Figure 1).

In his long career of service to his patients and to the mental health community—and, in particular, through his editorship of Psychiatric Services—John Talbott identified the central issues of our field in his time. Through his deeply held values, personal energy, and elegant style he gave us a model of a man to emulate for all times.

Dr. Rosenheck is affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Northeast Program Evaluation Center, VA Connecticut Healthcare System, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]). This commentary is part of a tribute to John A. Talbott, M.D., Editor Emeritus, who served as Editor of Hospital and Community Psychiatry and Psychiatric Services from 1981 to 2004.

Figure 1. Interventions to combat fragmentation of mental health services

1. Von Hoffman A: House by House, Block by Block: The Rebirth of America's Urban Neighborhoods. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003Google Scholar

2. Appelbaum PS: Response to the presidential address: the systematic defunding of psychiatric care: a crisis at our doorstep. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:1638–1640, 2002Link, Google Scholar

3. Lehman A, Postrado L, Roth D, et al: Continuity of care and client outcomes in the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Program on chronic mental illness. Millbank Quarterly 72:105–122, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Bickman L, Guthrie PR, Foster EM, et al: Evaluating Managed Mental Health Services: The Fort Bragg Experiment. New York, Plenum, 1995Google Scholar

5. Goldman HH, Morrissey J, Rosenheck RA, et al, and the ACCESS National Evaluation Team: Lessons from the evaluation of the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 53:967–970, 2002Link, Google Scholar

6. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:789–796, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Rosenheck RA, Perlick D, Bingham S, et al, for the Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on the Cost-Effectiveness of Olanzapine: Effectiveness and cost of olanzapine and haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia. JAMA 290:2693–2702, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Sernyak MJ, Leslie D, Alarcon R, et al: Association of diabetes mellitus with use of atypical neuroleptics in the treatment of schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:561–566, 2002Link, Google Scholar

9. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273:1026–1031, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rosenheck RA, Kasprow W, Frisman LK, et al: Cost-effectiveness of supported housing for homeless persons with mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:940–951, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Drake RE, Goldman HH, Leff HS, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services 52:179–182, 2001Link, Google Scholar

12. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 2001Google Scholar