Response to Vocational Rehabilitation During Treatment With First- or Second-Generation Antipsychotics

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Second-generation antipsychotics may enhance the rehabilitation of individuals with schizophrenia. The authors hypothesized that clients receiving second-generation antipsychotics would use vocational rehabilitation services more effectively and would have better employment outcomes than those receiving first-generation antipsychotics. METHODS: Ninety unemployed clients with schizophrenia and related disorders who were beginning a vocational rehabilitation program were followed for nine months. Three groups were defined according to the medication in use at study entry: olanzapine (N=39), risperidone (N=27), or first-generation antipsychotics only (N=24). Participants were interviewed monthly. RESULTS: The olanzapine and risperidone groups did not differ on any employment outcomes. On most vocational indicators, clients receiving second-generation agents did not differ from those receiving first-generation agents. However, at nine months the second-generation group had a significantly higher rate of participation in vocational training; a trend was found toward a higher rate of paid employment. All groups showed substantial improvement in employment outcomes after entering a vocational program. CONCLUSIONS: The hypothesis that second-generation antipsychotics promote better employment outcomes than first-generation antipsychotics was not upheld. However, second-generation agents appear to be associated with increased participation in vocational rehabilitation.

Since the beginning of the deinstitutionalization era, many mental health professionals have been pessimistic about the capacity of people with schizophrenia to work. The competitive employment rate for clients with schizophrenia is typically 20 percent or lower (1). However, recent studies have shown that vocational services that follow certain evidence-based principles—such as rapid job search, job matches congruent with client preferences, integration of vocational and clinical services, and long-term support (2)—lead to better employment outcomes (3,4,5,6,7).

Most studies that evaluate vocational programs do not pay enough attention to the effect medications may have on vocational outcomes, despite the accepted view that appropriate medications in combination with best practices in psychiatric rehabilitation lead to greater improvements in rehabilitation outcomes than does either factor alone (8,9,10,11,12). By the same token, most studies that assess the effects of psychotropic medications lack any systematic attention to vocational interventions, which may partly explain the fact that these studies did not show any effect of medications on work outcomes (unpublished paper, Mintz J, Mintz LI, Hwang SS, et al, University of California, Los Angeles department of psychiatry, 1997). For the past two decades, few researchers have investigated whether antipsychotics or other medications affect work outcomes.

The introduction of second-generation antipsychotics has renewed interest in the role of medications in the rehabilitation process (13). Although the focus of medication comparisons continues to be on reducing symptoms and on minimizing adverse events (14,15,16,17,18,19,20), some research is beginning to examine the effect second-generation antipsychotics have on rehabilitation outcomes, such as quality of life and general role functioning (21,22,23,24,25,26).

A few recent studies have examined the effect of second-generation antipsychotics on employment. Several uncontrolled studies showed improved work outcomes over time after clients' medication was switched from a first-generation antipsychotic to clozapine (27,28) or olanzapine (29,30,31). However, studies that directly compared the effect of second- and first-generation antipsychotics on vocational outcomes have shown mixed results. One observational study found that clients receiving clozapine, risperidone, or olanzapine had a higher rate of employment than did those receiving a first-generation antipsychotic (32), whereas another study found no differences in employment outcomes between clients receiving olanzapine or risperidone and clients receiving first-generation antipsychotics (33). Another study found that clients whose medication was switched from a first-generation antipsychotic to olanzapine had higher levels of psychosocial functioning than clients who received first-generation antipsychotics, after clients who were in psychotic relapse at baseline were excluded (31).

The most rigorous evaluation of a second-generation agent on work outcomes was a double-blind randomized controlled trial that compared 520 study participants who received olanzapine with 258 participants who received haloperidol (34). The trial found a significantly higher competitive employment rate at one year among olanzapine-treated participants than among those treated with haloperidol (15 percent compared with 5 percent). However, this study made no provision for vocational services, which may explain the low employment rates in both groups. Finally, studies have found that clients who receive olanzapine have vocational outcomes comparable to those of clients who receive risperidone (33,35).

Our study addressed the gap in current research by examining the effect of medications on work outcomes in the context of high-quality vocational rehabilitation services. We hypothesized that, among clients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders who entered comprehensive, vocationally oriented psychiatric rehabilitation programs, those who received a second-generation antipsychotic, either olanzapine or risperidone, would have better employment outcomes at follow-up than those who received first-generation antipsychotics only.

Methods

This study used a longitudinal design, in which changes were observed over a nine-month period among clients who were recently admitted to a psychiatric rehabilitation program. The study was approved by the Indiana University institutional review board. Data for this report were obtained from a larger study examining a range of clinical and neuropsychological measures obtained at baseline and at nine months (36). In this report we limit our focus to the employment outcomes.

Study participants were recruited from Thresholds, a Chicago-based agency (N=67), and four community mental health centers (CMHCs) in Indianapolis (N=23), from March 1999 to January 2001. Thresholds is a psychiatric rehabilitation agency that provides intensive vocational services in a stepwise manner, including unpaid work crews as well as group and individual work placements arranged between Thresholds and employers, enclaves, and agency-run businesses as well as independent jobs (37). Although this vocational approach differs in several respects from supported employment, it shares some common evidence-based principles of operation, including a focus on rapid placement into community jobs, the integration of treatment and vocational services, and the provision of long-term support (5). The participating CMHC study sites used an individual placement model of supported employment (38). A minority (N=13) of study participants from Thresholds received individual-placement supported employment in lieu of the stepwise vocational services Thresholds' clients receive.

Clients were eligible to participate in the study if they were unemployed, were between the ages of 18 and 64 years, expressed a goal of obtaining paid employment, had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and were currently receiving an antipsychotic—excluding clozapine, which is recommended for use among treatment-resistant patients. Clients who gave informed consent were enrolled in the study within 120 days of their admission to Thresholds or to one of the participating CMHC supported employment programs. Clients who did not maintain their antipsychotic regimen for at least two-thirds of the follow-up period—that is, six months—were excluded from the analysis.

During the study recruitment period, 551 clients were admitted to the study sites; out of this sample, 124 clients met the eligibility criteria and completed the baseline interviews. Of these, eight—three receiving olanzapine, two receiving risperidone, and three receiving first-generation antipsychotics only—discontinued services within the study period and were not included in the analyses. An additional 26 were excluded because they did not fall into one of the defined medication groups—six were receiving quetiapine, four were concurrently receiving two second-generation antipsychotics, and 16 clients changed medications, which precluded their classification into a specific medication group.

The final sample consisted of 90 study participants: 66 who were receiving olanzapine or risperidone and 24 who were receiving first-generation antipsychotics only. Within the olanzapine sample, 32 were receiving olanzapine only and seven were receiving olanzapine plus a first-generation antipsychotic. In the risperidone group, 24 were receiving risperidone only and three were receiving risperidone plus a first-generation antipsychotic. Five patients in the first generation group were prescribed two first-generation antipsychotics. All of the analyses reported below were repeated for each monotherapy subgroup, and the results were very similar to those for the full olanzapine and risperidone groups; therefore, we report only the findings for the full sample.

Data collection

Clients consecutively admitted to the study sites were screened for possible study inclusion by using computerized records and caseworker reports. A research assistant then contacted each client, explained the study, determined interest in the study, and obtained written consent from clients who agreed to participate.

Chart diagnosis was used as a preliminary screen for study participation. To determine diagnostic eligibility, clients who consented to participate were assessed by using the psychotic, mood disorder, and bipolar modules of a computerized version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-A) (39) or the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (40). Study participants were paid $10 for completing this assessment.

Participants were interviewed at baseline and were interviewed monthly, either by phone or in person, for nine months. During the follow-up interviews, participants were asked about changes in medications and work status. Employment outcomes after program enrollment but before the baseline interview were coded from clients' self-reports and were corroborated by agency records. Clients were paid $5 for each completed monthly interview, $15 for the baseline interview, and $15 for the nine-month interview.

Measures

A battery of assessment instruments administered at the baseline interview included demographic characteristics, work history information, and clinical measures. It included the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (41), which was scored on the total score and five subscales (42).

Vocational status was coded according to an adaptation of the Work Placement Scale (33) by using an 8-point gradient. Vocational status included competitive employment, defined as a regular community job with nondisabled coworkers that pays minimum wage; individual placement, an agency-contracted community job; group placement, a paid community job at a site working alongside other clients; agency-run business, paid work activity at a business owned and run by the rehabilitation agency; sheltered workshop, a paid work activity licensed by the Department of Labor and paid on a piece-rate basis; casual labor, paid employment of a temporary or intermittent nature; prevocational training, unpaid work training at the rehabilitation agency; and no vocational activity, not engaged in employment or vocational training.

Three dichotomous measures were defined from this typology. The first seven categories (competitive employment through prevocational training) were collapsed to define any vocational activity. The first six categories (competitive employment through casual labor) were collapsed to define a measure of paid employment. Finally, the first two categories (competitive employment and individual placement) were collapsed to define integrated employment. In addition, the following employment outcomes were measured: paid employment at any time, weeks from program admission until starting first paid job, weeks of paid employment, total hours of paid employment, and total earnings from employment.

Distributional properties of the major outcome variables were examined for outliers and skew. When tests for normality and homogeneity of variance were significant, nonparametric tests were also used. For all analyses that compared medication groups, continuous variables were analyzed by using analyses of variance and post hoc t tests, and all categorical variables were analyzed by using chi square tests.

Because some client background variables have been shown to be significantly associated with work outcomes in some studies (43), we compared the background variables of all medication groups to help identify any potential confounders. Except where noted below, the medication groups did not differ on any background variables. Statistical control for these variables did not materially change the results; therefore, results of the statistical analyses that did not control for these variables are reported throughout. Correlations, analyses of variance, and chi square tests were used to examine associations with employment outcome.

We also examined trends in the monthly employment rates during the nine-month follow-up period by using the three dichotomous indicators: any vocational activity, paid employment, and integrated employment. To increase statistical power, and because no differences were found between the olanzapine and risperidone groups, the two groups were aggregated into a single second-generation group and were compared with the first-generation group. The monthly vocational status data were analyzed by using the SAS Macro GLIMMIX (44), which is a statistical package employing random effects logistic regression to model longitudinal data. Specifically, this analysis compared the rate of change, that is, the slope of the regression line, for the two groups. Time zero in the models was set as the date a study participant entered the rehabilitation program.

Results

Sample characteristics

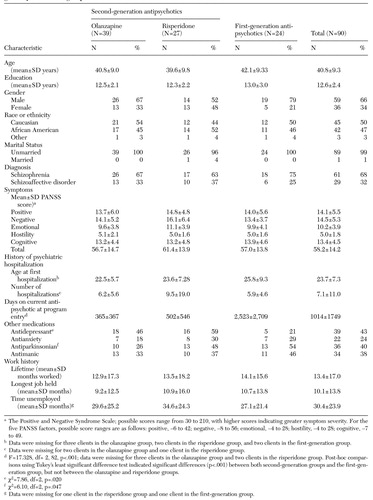

The three medication groups did not differ on most demographic or work history variables (Table 1). Although the three groups differed on the percentage of men and on percentage married, the comparisons of variables between first- and second-generation groups were not significant. Mean± SD baseline dosage levels of olanzapine, 12.9±7.0 mg, and risperidone, 5.4±2.8 mg, were within the range of recommended levels (45).

The three groups differed in the percentage of patients for whom two additional types of medications—antidepressants and antiparkinsonian medications—were prescribed. A significantly lower percentage of the first-generation group (21 percent) than of the second-generation group (52 percent) received a prescription for an antidepressant (χ2=6.75, df=1, p<.01). The difference between the percentage of the first-generation group receiving antiparkinsonian medication (54 percent) compared with the percentage of the first-generation group receiving antiparkinsonian medication (35 percent) approached significance (χ2=2.74, df=1, p<.10). Twelve participants in the first-generation group were receiving neuroleptics in depot form and 12 were receiving oral medication only. Because the oral and depot groups did not differ on a range of demographic or clinical measures examined, the first-generation group was treated as a single group.

Employment outcomes

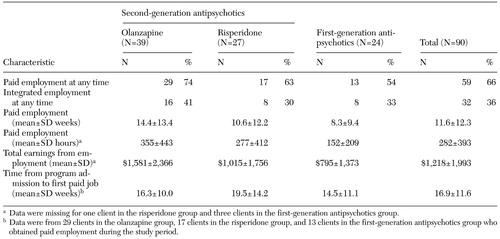

The first-generation group did not differ from the second-generation group on any of the six employment outcomes reported in Table 2. Post hoc comparisons between the olanzapine and risperidone groups suggested that they also did not differ on any of the employment outcome measures.

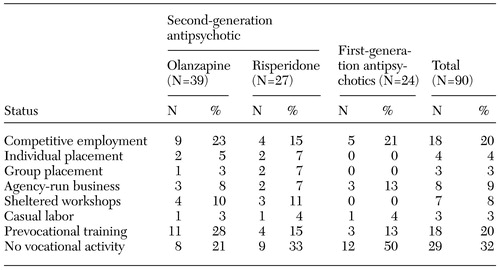

Employment status at nine-month follow-up for the three groups is shown in Table 3. After we combined data for the olanzapine and risperidone groups, we found that the first- and second-generation groups did not differ on paid employment (51 percent compared with 38 percent) nor in integrated employment (24 percent compared with 21 percent). However, a significantly higher percentage of the second-generation group was participating in some form of vocational activity—either working or receiving vocational training—at the nine-month follow-up, (76 percent compared with 50 percent; χ2= 5.74, df=1, p<.05).

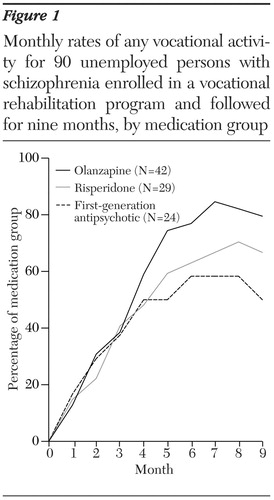

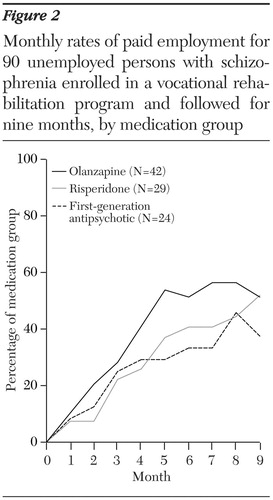

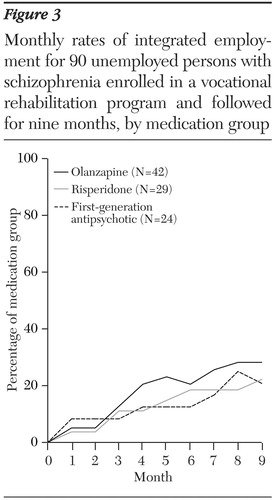

Monthly rates for any vocational activity, paid employment, and integrated employment for the olanzapine group, risperidone group, and first-generation antipsychotics only group are shown in Figures 1,2,3. The combined second-generation medication group was compared with the first-generation group by using random effects logistic regression. As expected, the entire study sample showed significant increases in vocational activity during the study period (t=4.25, df=718, p<.001). However, the rate of increase in vocational activity was significantly greater in the second-generation group than in the first-generation group (t=3.76, df=718, p=.001). The total sample also improved significantly in paid employment over time (t=4.86, df=718, p<.001). The interaction of rate of change (time × medication group) approached significance, suggesting weak evidence for a higher monthly rate of paid employment for the second-generation group compared with the first-generation group. Finally, integrated employment among all three groups increased significantly over time (t=3.57, df=718, p=.001), but the increase was not significantly greater in the second-generation group than in the first-generation group.

Discussion

This study was prompted by promising findings from earlier studies (31,33) that examined the potential for second-generation antipsychotics to enable people with schizophrenia and related disorders to achieve greater vocational gains. We hypothesized that persons receiving second-generation medications would demonstrate even stronger vocational gains than the gains that were hinted at in the literature (34) when these medications were provided in conjunction with vocationally oriented psychiatric rehabilitation services (8). We used a variety of employment indicators, but our study hypothesis was not upheld. Clients receiving first-generation antipsychotics did not differ from those receiving olanzapine or risperidone in nine-month employment outcomes. Consistent with our expectations and with the work of others (33), we found similar employment rates for the olanzapine and risperidone groups.

Although it was not the focus of the study, we confirmed that employment rates increased when vocational services that followed evidence-based principles were used. Not only did employment rates increase substantially from program admission to follow-up, but also the overall paid employment rate of 45 percent at the nine-month follow-up compares favorably with rates found in several surveys of employment rates among this population, including the study by Hamilton and colleagues (34), which demonstrated a 15 percent employment rate after a one-year follow-up period in a large clinical trial of olanzapine. It should be noted, however, that unlike in the study by Hamilton and colleagues, all of our study participants expressed a desire to work, which has been found to be associated with higher employment rates (1).

Despite the lack of employment differences between medication groups, some modest support was found for the hypothesis by Weiden and colleagues (13) that stated that second-generation antipsychotics may permit more clients to benefit from rehabilitation services. Specifically, compared with clients receiving first-generation antipsychotics, clients receiving second-generation antipsychotics remained involved longer in some form of vocational activity, even when they were not sustaining paid employment. Sustaining participation in vocational services is noteworthy, because of the widely replicated finding that clients who remain longer in vocational programs will eventually have better vocational outcomes (4). Thus, although second-generation antipsychotics may not yield improved short-term vocational outcomes, they may ameliorate the tendency some clients have to abruptly quit vocational programs.

Conversely, we speculated that clients receiving first-generation antipsychotics generally fall into two groups: those who respond well to their medication and achieve some measure of success in community jobs and those who get discouraged relatively quickly and stop participating in rehabilitation services, possibly precipitated in some cases by poor medication response. The reasons for greater participation by those in the second-generation group are not clear, but if this finding proves to be robust, it suggests one important benefit of prescribing a second-generation antipsychotic.

Several study limitations suggest that caution is needed in interpreting our findings, including low statistical power, a short follow-up period, and lack of randomization to remove any selection bias in the patients who entered the vocational program and which patients received which medication. Study participants differed widely in the length of time that they had been receiving medication, although these variables were unrelated to employment outcomes. Several outcome measures, including hours and weeks of paid employment as well as total earnings, had great between-subject variability. For each of these outcome measures, the mean levels for one or both of the second-generation groups were about twice that for the first-generation group, but the levels were still within the range attributable to random error. A much larger study would be required for sufficient power to detect clinically meaningful differences in these measures. The fact that participants in our study entered a vocationally oriented rehabilitation program suggests motivation to pursue recovery goals; therefore, our results cannot be generalized to all persons with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders.

Most study participants had been using their medication for more than six months, and so the groups may have consisted primarily of clients responding well to their prescribed antipsychotic. The fact that patients in the first-generation group in this study had not had their medications switched despite a general movement in treatment toward second-generation medications (46) may indicate that these clients were responding well to the first-generation antipsychotic. Other medication factors confounding the results included variability in medication dosages and considerable use of antiparkinsonian medications and of polypharmacy involving two or more antipsychotics. All of these confounding factors reflect the "real world" nature of this study, in which prescribing patterns are quite variable, but we cannot rule out the role of these factors in increasing variability of response and masking differences between groups.

Another factor of importance in enhancing the effectiveness of any medication is the application of evidence-based principles of medication management, for example, the close monitoring of adverse events, prescribing the lowest effective dose, paying attention to consumer preferences, and behavioral tailoring, that is, fitting medication taking into daily routines (47). This study did not measure the extent to which these principles were followed. Future studies should include routine assessment of fidelity to these principles.

Conclusions

It appears that the medication in use by persons entering vocational rehabilitation services did not have a dramatic effect on employment outcomes over a nine-month period, beyond the large effects already associated with vocational rehabilitation services. Whether the increased participation in vocational rehabilitation found for clients who received second-generation antipsychotics will translate into better employment outcomes over a longer period can best be answered by a future study with a longer follow-up period.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from Eli Lilly and Company. Our thanks to Alan McGuire and Marc Lauritano for their help in data analysis.

Dr. Bond and Dr. Evans are affiliated with the department of psychology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, 402 North Blackford Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46202-3275 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Kim is with Indiana University School of Social Work in Indianapolis. Dr. Meyer is with the University of North Carolina Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research in Chapel Hill. Dr. Gibson is with the Health and Hospital Corporation of Marion County in Indianapolis. Dr. Tunis is with Eli Lilly and Company in Indianapolis. Dr. Lysaker is with Roudebush Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Indianapolis. Dr. McCoy is with Westat in Rockville, Maryland. Dr. Dincin is with Thresholds in Chicago. Dr. Xie is with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center in Lebanon.

Figure 1. Monthly rates of any vocational activity for 90 unemployed persons with schizophrenia enrolled in a vocational rehabilitation program and followed for nine months, by medication group

Figure 2. Monthly rates of paid employment for 90 unemployed persons with schizophrenia enrolled in a vocational rehabilitation program and followed for nine months, by medication group

Figure 3. Monthly rates of integrated employment for 90 unemployed persons with schizophrenia enrolled in a vocational rehabilitation program and followed for nine months, by medication group

|

Table 1. Characteristics at baseline interview of 90 unemployed persons with schizophrenia enrolled in a vocational rehabilitation program, by medication group

|

Table 2. Work outcomes at nine-month follow-up for 90 unemployed persons with schizophrenia enrolled in a vocational rehabilitation program, by medication group

|

Table 3. Employment status at nine-month follow-up for 90 unemployed persons with schizophrenia enrolled in a vocational rehabilitation program, by medication group

1. Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Mueser PR: A prospective analysis of work in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:281–296, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bond GR: Principles of the individual placement and support model: empirical support. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:11–23, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: An update on supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:335–346, 1997Link, Google Scholar

4. Bond GR: Vocational rehabilitation in Handbook of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Edited by Liberman RP. New York, Macmillan, 1992Google Scholar

5. Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR, et al: Effectiveness of psychiatric rehabilitation approaches for employment of people with severe mental illness. Journal of Disability Policy Studies 10:18–52, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313–322, 2001Link, Google Scholar

7. Lehman AF: Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:645–656, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bond GR, Meyer PS: The role of medications in the employment of people with schizophrenia. Journal of Rehabilitation 65 (4):9–16, 1999Google Scholar

9. Corrigan PW, Penn DL: The effects of antipsychotic and antiparkinsonian medication on psychosocial skill learning. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2:251–262, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Hogarty G, Goldberg S: Drug and sociotherapy in the aftercare of schizophrenia patients: one-year relapse rates. Archives of General Psychiatry 28:54–64, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Schade ML, Corrigan PW, Liberman RP: Prescriptive rehabilitation for severely disabled psychiatric patients. New Directions for Mental Health Services 45:3–7, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Schwarzkopf SB, Crilly JF, Silverstein SM: Therapeutic synergism: optimal pharmacotherapy and psychiatric rehabilitation to enhance functional outcome in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 3:124–147, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Weiden PJ, Aquila R, Standard J: Atypical antipsychotic drugs and long-term outcome in schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 11):53–60, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

14. Casey DE: Side effect profiles of new antipsychotic agents. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 11):40–45, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

15. Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, et al: Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. British Medical Journal 321:1371–1376, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Leucht S, Pitschel-Walz G, Abraham D, et al: Efficacy and extrapyramidal side-effects of the new antipsychotics olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and sertindole compared to conventional antipsychotics and placebo. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Schizophrenia Research 35:51–68, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Moller HJ, Muller H, Borison RL, et al: A path-analytical approach to differentiate between direct and indirect drug effects on negative symptoms in schizophrenic patients. A re-evaluation of the North American risperidone study. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 245:45–49, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Rabinowitz J, Bromet EJ, Davidson M: Short report: comparison of patients satisfaction and burden of adverse effects with novel and conventional neuroleptics: a naturalistic study. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:597–600, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Tamminga CA: The promise of new drugs for schizophrenia treatment. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:265–273, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Tollefson GD, Beasley CM Jr, Tran PV, et al: Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders: results of an international collaborative trial. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:457–465, 1997Link, Google Scholar

21. Franz M, Lis S, Pluddemann K, et al: Conventional versus atypical neuroleptics: subjective quality of life in schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 170:422–425, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Meltzer HY, Burnett S, Bastani B, et al: Effects of six months of clozapine treatment on the quality of life of chronic schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:892–897, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Meltzer HY, Cola P, Way L: Cost effectiveness of clozapine in neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1630–1638, 1993Link, Google Scholar

24. Tunis SL, Johnstone BM, Gibson J, et al: Changes in perceived health and functioning as a cost-effectiveness measure for olanzapine versus haloperidol treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 19):38–45, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

25. Rosenheck R, Tekell J, Peters J, et al: Does participation in psychosocial treatment augment the benefit of clozapine? Archives of General Psychiatry 55:618–625, 1998Google Scholar

26. Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, et al: The National Institute of Mental Health Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Project: schizophrenia trial design and protocol development. Schizophrenia Bulletin 29:15–31, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Lindström LH, Lundberg T: Long-term effect on outcome of clozapine in chronic therapy-resistant schizophrenic patients. European Psychiatry 12(suppl 5):353s-355s, 1997Google Scholar

28. Littrell K: Maximizing schizophrenia treatment outcomes: a model for integration. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:75–77, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Noordsy D, O'Keefe C: Effectiveness of combining atypical antipsychotics and psychosocial rehabilitation in a CMHC setting. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 19):47–51, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

30. Noordsy DL, O'Keefe C, Mueser KT, et al: Twelve-month outcomes for patients switched to olanzapine in community psychiatric care. Poster presented at the Institute on Psychiatric Services, Philadelphia, Oct 25–29, 2000Google Scholar

31. Noordsy D, O'Keefe C, Mueser KT, et al: Six-month outcomes for patients who switched to olanzapine treatment. Psychiatric Services 52:501–507, 2001Link, Google Scholar

32. McGurk SR, Meltzer HY: The role of cognition in vocational functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research 45:175–184, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Meyer PS, Bond GR, Tunis SL, et al: Comparison between the effects of atypical and traditional antipsychotics on work status for clients in a psychiatric rehabilitation program. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:108–116, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Hamilton SH, Edgell ET, Revicki DA, et al: Functional outcomes in schizophrenia: a comparison of olanzapine and haloperidol in a European sample. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 15:245–255, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Weiden PJ, Aquila R, Kinon BJ, et al: Effectiveness of olanzapine upon psychiatric and vocational rehabilitation outcomes. Poster presented at the Institute on Psychiatric Services, New Orleans, Oct 1999Google Scholar

36. Bond GR, Kim HW, Meyer P, et al: Longitudinal impact of second generation antipsychotics and psychiatric rehabilitation: final report submitted to Health Outcomes Evaluation Group, Lilly Research Laboratories, Eli Lilly and Company. Indianapolis, Ind, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, 2002Google Scholar

37. Koop J, Rollins AL, Bond GR, et al: Development of the DPA Fidelity Scale: using fidelity to define an existing vocational model. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, in pressGoogle Scholar

38. Vogler KM: A fidelity study of the Indiana Supported Employment Model for individuals with severe mental illness in Psychology. Indianapolis, Ind, Indiana University- Purdue University Indianapolis, 1998Google Scholar

39. CIDI-Auto Version 2.1: Administrator's Guide and Reference. St. Louis, Training and Reference Centre for the World Health Organization CIDI, 1997Google Scholar

40. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders—Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0). New York, Biometric Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1994Google Scholar

41. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261–276, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

42. Bell MD, Lysaker PH, Beam-Goulet JL, et al: Five-component model of schizophrenia: assessing the factorial invariance of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Psychiatry Research 52:295–303, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Cook J, Razzano L: Vocational rehabilitation for persons with schizophrenia: recent research and implications for practice. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:87–103, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Littell R, Milliken G, Stroup W, et al: SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, Inc., 1996Google Scholar

45. Lehman AF, Schizophrenia PORT Team: Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Treatment Team (PORT) Treatment Recommendations:2003 Update. Baltimore, University of Maryland School of Medicine/ Johns Hopkins University Center for Research on Services for Severe Mental Illness, 2003Google Scholar

46. Wang PS, West JC, Tanielian T, et al: Recent patterns and predictors of antipsychotic medication regimens used to treat schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:451–457, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Mellman TA, Miller AL, Weissman EM, et al: Evidence-based pharmacologic treatment for people with severe mental illness: A focus on guidelines and algorithms. Psychiatric Services 52:619–625, 2001Link, Google Scholar