Traumatic Life Events and PTSD Among Women With Substance Use Disorders and Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors assessed the prevalence of traumatic life events and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among women with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and co-occurring substance abuse or dependence. The association between PTSD and specific traumatic life events was also examined. METHODS: Fifty-four drug-addicted women with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder participated in the study. All women were psychiatric outpatients and completed a large battery of structured clinical assessments. RESULTS: High rates of trauma, particularly physical abuse (81 percent), and revictimization—being abused both as a child and as an adult—were reported. The average number of traumatic life events reported was eight, and almost three-quarters of the sample reported revictimization. Rates of current PTSD were considerably higher than those documented in previous study samples of persons with serious mental illness and of drug-addicted women in the general community. PTSD was significantly associated with childhood sexual abuse and revictimization. CONCLUSIONS: The high levels of trauma and revictimization observed in the study highlight the need for the development of evidence-based interventions to treat trauma and its aftermath among women with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Given the overlap in symptoms between PTSD and schizophrenia, a better understanding is needed of how PTSD is expressed among people with schizophrenia. Recommendations and standards for the assessment of PTSD among this population need to be articulated. Finally, the comparatively high rates of PTSD suggest that the combination of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and substance use disorder makes these women particularly vulnerable to adverse outcomes.

The need for research on women who have both substance use disorders and schizophrenia is tremendous. Substance use is a pervasive problem among people with serious mental illness and is linked with numerous adverse outcomes, including a more severe course of illness, more severe symptomatology, and higher rates of rehospitalization, treatment noncompliance, and housing instability (1,2). Substance use is also on the rise among women (3,4,5). Evidence suggests that the combination of using substances and having a serious mental illness may substantially raise women's risk of trauma exposure and its associated adverse outcomes. In a study of sexual and physical abuse among 275 seriously mentally ill patients, 52 percent of the women surveyed reported having experienced adult sexual abuse and 36 percent adult physical abuse (6). In another study of trauma among 158 seriously mentally ill outpatients, 55 percent of women reported having experienced adult sexual abuse and 47 percent adult physical abuse (7).

Drug use has also been linked with higher rates of sexual and physical abuse in women with no history of serious mental illness (8). The context of drug use and being intoxicated make women more vulnerable to victimization. In studies of more than 520 drug-abusing women with no history of serious mental illness, between 44 percent and 59 percent of women reported sexual abuse and between 55 percent and 67 percent reported physical abuse (9,10). These data indicated that the rates of sexual and physical abuse observed among women with serious mental illness as well as among drug-abusing women without serious mental illness are considerably higher than the rates observed among women in the general population. In large epidemiological community studies, the prevalence of sexual abuse ranges between 7 percent and 13 percent and the prevalence of physical abuse ranges between 7 percent and 12 percent (11,12,13).

Not surprisingly, rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a common and devastating outcome associated with sexual and physical abuse, are elevated in samples of people with serious mental illness as well as in samples of women with substance use disorders. In perhaps the best-known study of trauma exposure among psychiatric outpatients, 43 percent of 275 patients reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD, and approximately 30 percent of 94 patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder screened positive for PTSD (6). Another study focusing specifically on domestic violence among psychiatric inpatients found that 29 percent of the 69 patients in the sample had PTSD (14). In a multisite study of cocaine treatment for individuals without serious mental illness, 30 percent of 43 women met criteria for current PTSD (15). Other studies of PTSD among drug-abusing women obtained similar results: prevalence rates of current PTSD ranged from 30 percent to 37 percent (9,16). These rates of PTSD, both among patients with serious mental illness and among women with substance use disorders, greatly exceed the current prevalence rate of 8 percent to 9 percent documented for women in the general population (11,13).

Despite this potentially higher risk of adverse outcomes, we know little about the nature and extent of trauma and PTSD among women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia. The difficulties linked with schizophrenia, such as cognitive impairments, poor social skills, and poor social-problem-solving ability, combined with the negative consequences associated with substance abuse among women, may make this population particularly vulnerable to sexual and physical abuse and associated adverse outcomes.

The purposes of our descriptive study were to assess the prevalence of traumatic life events and PTSD among women with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and co-occurring drug abuse or dependence and to examine the association between specific traumatic life events and PTSD. We hypothesized that the prevalence of trauma and PTSD in a well-defined sample of drug-using or drug-dependent women with schizophrenia would exceed previously observed rates in heterogeneous samples of women with serious mental illness as well as samples of drug-dependent women from the general population. To our knowledge, no study has examined the prevalence of trauma and PTSD in the marginalized and understudied population of women with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and co-occurring drug use disorders.

Methods

Participants and setting

The study participants were 54 women with DSM-IV diagnoses of either schizophrenia (33 of 54, or 61 percent) or schizoaffective disorder (21 of 54, or 39 percent) and current illicit-drug abuse or dependence (past three months). All women were receiving outpatient mental health treatment at inner-city community-based clinics affiliated with the University of Maryland (N=51) or the Veterans Administration Medical Center (N=3) in Baltimore and were stable psychiatrically. The mean±SD positive-symptom clinical rating from the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (17) (range, 0, not at all, to 7, extreme) was 2.54±.71, and the negative-symptom rating was 2.52±.7. The additional eligibility criteria included an age range of 18 to 65 years. Exclusion criteria were mental retardation and a documented history of seizure disorder or head trauma with loss of consciousness. Baseline data for the 54 women were collected from March 1999 to June 2002 for a longitudinal study of trauma among women with schizophrenia and substance use disorders.

The mean±SD age of the women was 40.6±6.8 years. The women had completed a mean of 10.9±2 years of school. Of the total sample, 50 (92 percent) were African American, 37 (69 percent) had never been married, 47 (87 percent) met criteria for either illicit-drug abuse or dependence, and eight (14 percent) met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence only. Forty-two percent of the participants met criteria for both illicit-drug abuse or dependence and an alcohol use disorder. As the primary drug of abuse, 45 (84 percent) of the women who used drugs reported cocaine, six (11 percent) cannabinoids, and two (4 percent) opioids.

Medical charts were reviewed to determine preliminary eligibility for the study. Therapists of eligible patients were then asked whether patients were sufficiently psychiatrically stable to provide informed consent. All potential participants took part in a standardized informed-consent process with trained recruiters. Individuals were read the informed-consent document and were then asked questions about the study requirements and the risks and benefits of study participation to determine whether they clearly understood what was being asked of them. Women who were unable to answer these routine questions were reread the consent document and asked again, and women unable to understand the study requirements were excluded. All assessments and procedures were reviewed and approved by the university and the VA Maryland Health Care System institutional review board.

Assessment measures

Each participant was administered a four-hour assessment battery over a two-day period. All research interviewers were women who had master's or doctoral degrees. The first author trained the clinical interviewers with reading materials, training tapes, and live supervision. Interviewers approved for beginning the assessments attended weekly group supervision sessions where videotaped assessments were reviewed and discussed. Ongoing interrater reliability was maintained by obtaining consensus on ratings of symptom intensity and severity as well as diagnosis for randomly selected study participants during weekly supervision sessions.

Diagnosis and symptom assessment. Information about current symptoms and psychiatric history was obtained with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (18). To evaluate diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and substance use disorders, the SCID was used, as well as all available information for the patient—the patient's self-report, medical records, and information from treatment providers. The interrater reliability rating (kappa) for the SCID diagnoses (psychiatric disorders and substance abuse or dependence), based on ratings of 21 randomly selected cases, was greater than .80. Patients for whom diagnoses were uncertain were considered ineligible to participate. This group included all patients whose psychotic symptoms were judged to be substance induced.

Lifetime trauma history assessment. Lifetime trauma history was assessed with the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ) (19). This instrument covers a range of commonly assessed childhood and adulthood events. The interview assesses both exposure to the event and individuals' subjective reaction to the event. Assessing subjective reaction—for example, self-reported feelings of terror, horror, or threat to life—is necessary for determining whether the event can be considered a DSM-IV criterion A event for PTSD.

Evidence indicates that the reliability over time of self-reports of trauma by women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia is quite satisfactory. Fourteen participants in our study were administered the TLEQ at baseline and then again seven to 10 days later. Kappa coefficients were calculated to determine agreement for the presence or absence of adult sexual and physical abuse as well as for the number of traumatic events reported. A kappa of .85 was obtained for adult sexual victimization, .60 for adult physical victimization, and .76 for the total number of lifetime traumatic events reported. Other studies have demonstrated good reliability for the reports of sexual and physical abuse by people with serious mental illnesses (20,21; unpublished paper, Gearon JS, Bellack AS, Tenhula W, 2003).

Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder. The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) (22) is a clinician-administered interview that measures PTSD diagnostic criteria. The CAPS was developed to enhance the validity and reliability of PTSD diagnoses. Each of the 17 DSM-IV PTSD symptoms is rated on a scale of 0, low, to 4, high, for both frequency and intensity. PTSD symptom severity is computed by summing the frequency and intensity scores for the 17 items. The PTSD diagnosis was established by using the recommended cutoff of total severity of symptoms: 45 or higher (23). This cutoff criterion was selected to enable us to compare our findings with those observed in previous studies: Meuser and colleagues' (6) preliminary study of PTSD and trauma among patients with serious mental illness, as well as several existing studies of PTSD among substance-abusing women from the general community (9,10,11) that used screening criteria or self-report instruments.

The CAPS offers a more rigorous and valid approach for estimating the prevalence of PTSD than does a brief screening or a self-report instrument, because it is an interview relying on clinical judgment. The interview also provides explicit anchors and behavioral referents for guiding ratings, which gives it reliability and validity above and beyond that of other instruments assessing PTSD.

The CAPS was adapted for use with patients with schizophrenia by making symptom descriptions more concrete and by providing more behaviorally specific examples. For example, DSM-IV criterion C1, "efforts to avoid thoughts, feelings, or conversation associated with the trauma," is assessed with multiple questions, including these: "Have you tried not to talk to people (like your therapist, case manager, psychiatrist, friends, or family) about the event? Is it hard to talk about it now? Are you trying to push away thoughts or feelings about the event right now?" On the basis of Kessler's recommendation (12), and because the majority of women with schizophrenia have experienced multiple traumatic events, questions about intrusion and avoidance that are typically asked in reference to a particular traumatic event were asked with respect to the range of traumatic experiences the participants reported.

Interrater reliability for our PTSD interviewers was excellent: intraclass coefficients for the symptom clusters and total severity of symptoms ranged from .97 to .99 for a subsample of eight participants, five of whom had a current diagnosis of PTSD. The level of agreement between interviewers in PTSD diagnosis, as indicated by the kappa coefficient, .90, was excellent as well.

Indexes of internal consistency suggest that the CAPS is internally stable and reliable. Coefficient alphas indicate that criteria in each of the three symptom clusters—for example, reexperiencing, avoidance, and arousal—and the total severity of symptom scores represent unified constructs. For our study participants, alpha was .91 for reexperiencing, .82 for avoidance, .86 for arousal, and .76 for the total severity of PTSD symptoms. The CAPS total symptom severity score and the three-symptom cluster scores appear to be reliable over time as well. Intraclass coefficients calculated at baseline and then again seven to ten days later for 14 participants were all satisfactory: reexperiencing, .62; avoidance, .80; arousal, .79; and total severity, .85.

Data analysis

The association between specific traumatic life events and current PTSD was assessed in two ways. First, Fisher's exact tests of the null hypothesis—that experiencing physical or sexual abuse is independent of PTSD diagnosis—was performed. Second, t tests were performed to test the difference in means between those reporting and those not reporting specific traumatic events. To control for type I errors, the alpha level was set to .01 for all comparative analyses. Findings with p values less than .05 but greater than .02 were considered marginal.

Results

Prevalence of trauma exposure

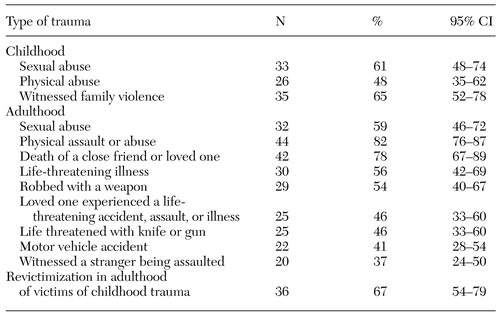

Almost the entire sample (96 percent) reported experiencing at least one lifetime traumatic event. The mean±SD number of traumatic events was 8.1±3.8. The median was 9.0. The proportions of women experiencing particular types of trauma in childhood and as adults are provided in Table 1.

Rates of sexual and physical abuse in the sample were very high. Childhood sexual abuse was reported by 61 percent of the sample and childhood physical abuse by 48 percent. Adult sexual abuse was reported by 59 percent and adult physical abuse by 82 percent. Two-thirds of the sample were revictimized—that is, experienced both childhood and adult sexual or physical abuse. The death of a close friend or loved one (78 percent), witnessing family violence as a child (65 percent), and experiencing a life-threatening illness (56 percent) were also frequently reported.

PTSD and types of trauma exposure

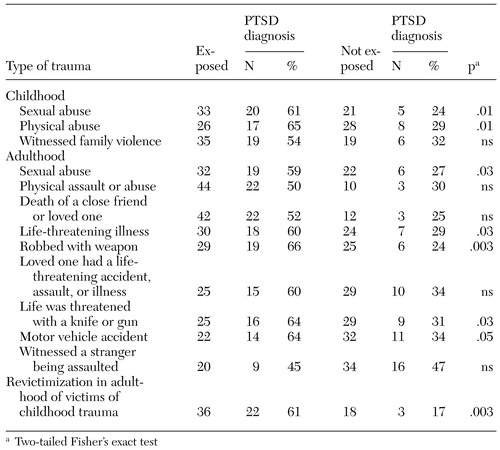

In our sample, 25 of the 54 women (46 percent) met criteria for current PTSD. Table 2 presents a comparison of the proportion diagnosed with PTSD between those exposed and those not exposed to the various traumatic events. Significance levels determined by Fisher's exact test are provided. Childhood sexual abuse and physical abuse were significantly associated with current PTSD. Also associated with PTSD were revictimization and being robbed with a weapon.

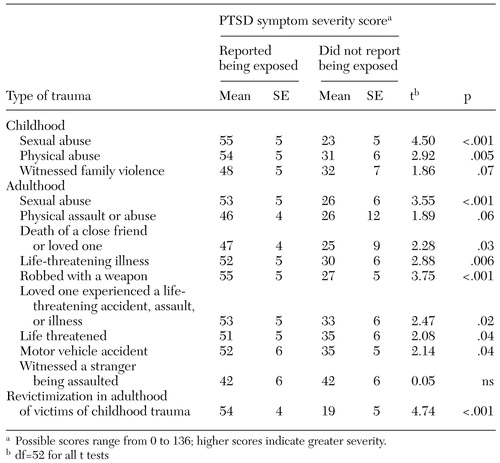

Table 3 shows the mean PTSD symptom severity scores by type of event reported. For the majority of traumatic events, clear differences in mean PTSD symptom severity scores, ranging from a difference of 16 points to a difference of 32 points, existed between those who had experienced and those who had not experienced the event. The largest differences were associated with sexual abuse—both childhood, a difference of 32 points, and adult, a difference of 27 points. Other statistically significant differences were found between those who had and had not experienced revictimization (30 points), being robbed with a weapon (27 points), childhood physical abuse (22 points), and life-threatening illness (22 points).

Discussion

High rates of trauma, including sexual and physical abuse and revictimization, were observed in our sample of women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia. The level of trauma exposure was similar to that found in earlier studies of trauma among patients with serious mental illness, but this level was considerably higher than that observed in other samples of substance-abusing women. In two studies of inner-city cocaine-addicted women, the average number of traumatic life events documented for the participants was five (15,24), compared with eight observed in our study sample. This finding is clinically meaningful, because other studies suggest that the likelihood of a diagnosis of PTSD is greater among women exposed to a greater number of traumas (15,24).

Rates of adult physical abuse in our study were also higher than those documented in previous studies of patients with serious mental illness and drug-addicted women from the community. In our study, 81 percent of the women reported physical abuse, compared with the 36 percent of the women who reported abuse in Meuser and colleagues' well-known investigation of trauma among patients with serious mental illness (6). In addition, our observed rate of 81 percent is slightly higher than the rates documented in demographically similar studies of drug-addicted women. In two studies of primarily cocaine-addicted women, between 55 percent and 67 percent reported adult physical abuse (9,25). These data suggest that women with schizophrenia who have substance use disorders are at particular risk of physical abuse. Additional studies, however, are obviously needed to determine empirically whether this increased risk of physical abuse is related to substance use factors—for example, drug of choice or severity of substance use—or having schizophrenia, or both.

As hypothesized, the prevalence rate of 46 percent for current PTSD among our sample of women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia was considerably higher than the 8.8 percent prevalence rate of current PTSD observed in the general population of women, as well as the rate documented by Mueser and colleagues (6) for patients with schizophrenia (30 percent) and rates observed in samples of women with drug use disorders and no history of serious mental illness—30 percent to 37 percent (9,15,16). Because we used gold-standard clinical interviews, as opposed to screening instruments or self-report measures, to establish a diagnosis of current PTSD, our level of confidence in the prevalence estimate is high. Importantly, this comparatively higher rate of current PTSD suggests a potential vulnerability to PTSD among women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia.

As in the general population, childhood sexual abuse was strongly associated with PTSD. Sizable differences in PTSD symptom severity were also found between those reporting childhood sexual abuse and those not reporting it. Although the cross-sectional nature of our study limited our ability to determine causality between exposure to specific traumatic events and PTSD, the fact that similar associations have been repeatedly documented in a variety of different samples across different settings increases our confidence in the results (24,26).

A significant link between PTSD and revictimization was also found. This finding is intuitive, and it has been documented among samples of inner-city cocaine-addicted women (8,15), but it has not been previously established among samples of women with serious mental illness.

The results of our study must be qualified by a few methodological limitations. First, the exclusive use of women with schizophrenia and co-occurring substance use disorders—primarily cocaine-dependent African-American women—may limit the generalizability of the findings. The positive side of this limitation, however, is that the well-defined sample makes it clear to whom the results are applicable. Another limitation is the fact that this was a sample of convenience. A random sample of women with schizophrenia would have helped reduce any potential sample biases.

Conclusions

The results of our study raise important issues. First, the high levels of trauma, revictimization, and associated suffering in our sample underscore the need to develop evidenced-based interventions to treat trauma and its aftermath among women who have substance use disorders and schizophrenia, as well as to develop preventive interventions to reduce the risk of revictimization.

Second, studies examining the context of abuse would be informative. In what types of situations are women with schizophrenia sexually or physically abused—for example, social, familial, or drug-use situations? Are these situations similar to or different from those in which other women are abused? Who are the perpetrators—family, friends, or strangers? Do women with schizophrenia report criminal victimization to mental health providers or the police?

Third, the relationship between substance use and trauma exposure needs to be established by also examining traumatic life events and PTSD in a well-defined sample of women with schizophrenia who do not have substance use disorders.

Fourth, we need to better understand the interface between schizophrenia and PTSD. The similarity between the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and the avoidant symptoms of PTSD, as well as between flashbacks and hallucinations or delusions, raises the question of how PTSD is expressed by people with schizophrenia. For example, are the overlapping symptoms exaggerated among people with schizophrenia? Studies comparing PTSD symptom constellations among patients with schizophrenia and less-impaired patients could improve our understanding of this area. Finally, the overlap in symptoms between disorders calls for the development of recommendations or standards for assessment of PTSD among people with schizophrenia.

Despite the limitations of our study, the data are informative about the nature and extent of the problem of trauma and PTSD among women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia—a population of women that has remained virtually invisible and thus likely to be misunderstood and ineffectively treated.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant DA-11199-01 to Dr. Gearon and grant DA-11753 to Dr. Bellack and the VISN 5 Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. The authors thank Ye Yang, M.A., for her help with the data analyses.

Dr. Gearon is an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and associate director of the clinical core at the Veterans Administration Capitol Health Care Network Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center; Dr. Kaltman is an assistant professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University; Dr. Brown is an assistant professor of epidemiology and preventive medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine; and Dr. Bellack is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the director of the Veterans Administration Capitol Health Care Network Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Send correspondence to Dr. Gearon at the VA Maryland Health Care System, 10 North Greene Street, Suite 6A MIRECC, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Lifetime exposure to traumatic events in a sample of 54 women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia

|

Table 2. Diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among 54 women with substance use disorder and schizophrenia, by whether or not they were exposed to different types of trauma

|

Table 3. PTSD symptom severity score by type of trauma exposure in a sample of 54women with substance use disorders and schizophrenia

1. Osher FC, Drake RE, Noordsy DL, et al: Correlates and outcomes of alcohol use disorder among rural outpatients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55:109-113, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Levinson DF, et al: Prevalence of substance abuse in schizophrenia: demographic and clinical correlates. Schizophrenia Bulletin 16:31-56, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Canterbury RJ: Alcohol and other substance abuse, in Women's Mental Health: a Comprehensive Textbook. Edited by Kornstein SG, Clayton AH. New York, Guilford, 2001Google Scholar

4. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Main Findings 1998. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2000Google Scholar

5. Stein MD, Cyr MG: Women and substance abuse. Medical Clinics of North America 81:979-998, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Mueser K, Goodman L, Trumbetta S, et al: Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66:493-499, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Coverdale JH, Turbott SH: Sexual and physical abuse of chronically ill psychiatric outpatients compared with a matched sample of medical outpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:440-445, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Fullilove MT, Fullilove RE, Smith M, et al: Violence, trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder among women drug users. Journal of Traumatic Stress 6:533-543, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Dansky BS, Brady KT, Saladin ME, et al: Victimization and PTSD in individuals with substance use disorders: gender and racial differences. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 22:75-93, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Cottler LB, Nishith P, Compton WM: Gender differences in risk factors for trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder among inner-city drug abusers in and out of treatment Comprehensive Psychiatry 42:111-117, 2001Google Scholar

11. Norris F: Frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 60:409-418, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:1048-1060, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Resnick H, Kilpatrick D, Dansky B, et al: Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 61:984-991, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Cascardi M, Mueser K, DeGirolomo J, et al: Physical aggression against psychiatric inpatients by family members and partners: a descriptive study. Psychiatric Services 47:531-533, 1996Link, Google Scholar

15. Najavits LM, Gastfriend DR, Barber JP, et al: Cocaine dependence with and without PTSD among subjects in the National Institute on Drug Abuse Collaborative Cocaine Treatment Study. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:214-219, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Kukla RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, et al: Trauma and the Vietnam War Generation: Report of Findings From the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, Brunner/Mazel, 1990Google Scholar

17. Opler LA, Kay SR, Lindenmayer JP, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (SCI-PANSS). New York, Multi-Health Systems, 1992Google Scholar

18. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Clinician Version. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1997Google Scholar

19. Kubany E: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ): a brief measure of prior trauma exposure. Honolulu, Pacific Center for PTSD, 1995Google Scholar

20. Goodman LA, Thompson KM, Weinfurt K, et al: Reliability of reports of violent victimization and posttraumatic stress disorder among men and women with serious mental illness. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:587-599, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Mueser K, Rosenberg S, Fox L, et al: Psychometric evaluation of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder assessments in persons with severe mental illness. Psychological Assessment 13:110-117, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, et al: A clinical rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: the CAPS-1. Behavior Therapist 18:187-188, 1990Google Scholar

23. Weathers FW, Ruscio AM, Keane TM: Psychometric properties of nine scoring rules for the Clinician-Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale. Psychological Assessment 11:124-133, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

24. Back S, Dansky B, Coffey SF, et al: Cocaine dependence with and without post-traumatic stress disorder: a comparison of substance use, trauma history, and psychiatric co-morbidity. American Journal on Addictions 9:51-62, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Grice DE, Brady KT, Dustan LR, et al: Sexual and physical assault history and post-traumatic stress disorder in substance dependent individuals. American Journal of Addictions 4:297-305, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, et al: Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:902-907, 1999Link, Google Scholar