Factors That Explain How Policy Makers Distribute Resources to Mental Health Services

Abstract

Advocates hope to influence the resource allocation decisions of legislators and other policy makers to capture more resources for mental health programs. Findings from social psychological research suggest factors that, if pursued, may improve advocacy efforts. In particular, allocation decisions are affected by policy makers' perceptions of the scarcity of resources, effectiveness of specific programs, needs of people who have problems that are served by these programs, and extent of personal responsibility for these problems. These perceptions are further influenced by political ideology. Conservatives are motivated by a tendency to punish persons who are perceived as having personal responsibility for their problems by withholding resources, whereas liberals are likely to avoid tough allocation decisions. Moreover, these perceptions are affected by political accountability, that is, whether politicians perceive that their constituents will closely monitor their decisions. Just as the quality of clinical interventions improves when informed by basic research on human behavior, the efforts of mental health advocates will be advanced when they understand the psychological forces that affect policy makers' decisions about resources.

One truism in the public sector is that the need for funds to adequately support mental health services seems to far exceed available resources. Legislators and other policy makers must wade through competing sets of budgetary requests from all the programs supported by the government and decide how much to allocate to mental health services. To have some effect on this allocation process, mental health advocates must identify factors that influence key allocation decisions.

One way in which advocates try to affect the decisions of policy makers is through informing them about evidence of the effectiveness of various psychiatric services (1). The assumption is that policy makers who have this information will naturally support such practices. Fortunately, this assumption corresponds with decision research from social and political psychology that suggests that decisions about resource allocation are influenced by knowledge of the need and effectiveness of service options (2).

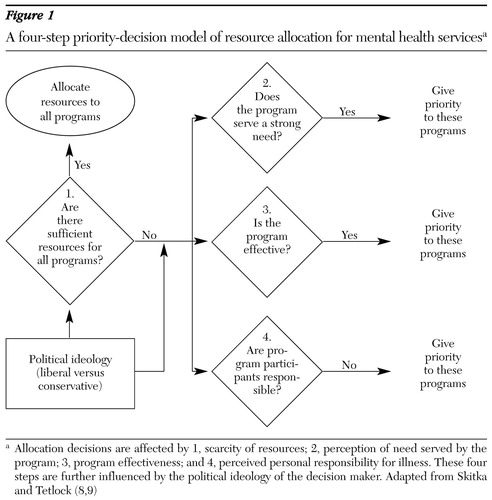

Moreover, psychological research has identified other factors that influence policy decisions. These factors include perceptions of resource scarcity, the political ideology of individual decision makers, and perceptions of responsibility for the recipient's problems that require service. In this article we provide a decision tree that summarizes this research so that advocates can be better informed about how to approach legislators and other policy makers about resource allocation. We further enhance this discussion by considering the psychological factors that affect how political accountability influences decision makers. We first review the extent of the resource problem.

The need for more resources

Consider the complexity of the allocation issue. First, legislators and policy makers must decide how to split revenue among the myriad of services the government supports. Human services are just one small portion of the vast portfolio of government programs. Within human services, many programs vie for what can seem to be a limited pot. These programs vary by state but may include public health programs, family planning programs, child and infant services, independent living services, and behavioral health services. Most states further divide behavioral health services into independent departments that serve people who have mental retardation, substance use disorders, or mental illness. The allocation task continues within departments of mental health that have a multitude of inpatient and outpatient or community-based services that need funds. Decisions about inpatient services must consider length of stay and the privatization of hospital programs. Community-based programs vary from traditional day treatment and medication management programs to more rehabilitative services, such as assertive community treatment, supported employment, supported housing, and supported education.

Resource needs become even more complex when lines blur between mental health and other human services. Policy makers must now grapple with budgetary requests to serve people with mental illness who also have substance use problems, struggle with family issues, or are involved in the criminal justice system. Finally, policy makers may have to decide who among those with mental health problems are most in need of services. Many government entities are focusing on serious mental illness and psychiatric disability as the priority for service funding.

The above discussion outlines the complexity only on the cost side of the allocation picture. What about revenues? The National Mental Health Association (3) stated that health care costs have continued to rise steeply over the past ten years while corresponding funds to support these services have leveled off. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (4), mental health and substance abuse expenditures represented only 7.8 percent of the more than $1 trillion of all U.S. health care expenditures in 1997. This finding is sobering given that the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study suggested that 7.3 percent of the adult population suffers from a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, major depression, or bipolar disorder. When all mental and addictive disorders are included, the one-year prevalence rate is 28 percent of the adult population (5). Moreover, 1997 expenditures represent a decrease from a decade earlier, when funding was 8.8 percent of total health care costs. Underfunding leads to inadequate provision of mental health services, especially to priority populations such as children and adults with serious mental illness (6).

The stinginess of policy makers seems to parallel the general public's hesitancy to more fully fund mental health services. In the 1996 General Social Survey—conducted by the National Opinion Research Center (7) every two years as a national snapshot of key social and political issues—almost half of respondents said they believed that mental health services should be supported "much less than," "less than," or "the same as" the current level. Public support for mental health funding was relatively low compared with support for other government services that same year. For example, 60 percent of survey respondents believed that the government should spend more on protecting the environment, and 70 percent wanted more spending on general health services, crime control, and education (7). The negative trend toward supporting mental health services leads to a key question for which advocates need answers if they are going to change the status quo: Why are legislators hesitant to more satisfactorily fund mental health programs?

Resource allocation as a decision-making process

An important series of studies by Skitka and Tetlock (2,8,9,10) have outlined some of the social psychological variables that affect decisions about resource allocation. On the basis of this work, we have provided a decision tree, shown in Figure 1, that suggests how priorities are made in terms of mental health funding. Variables in the model represent three broad concerns. First, what is the perception of overall resource availability? Policy makers will promise programs to meet all resource requests during times of prosperity when ample funds exist. Second, during periods of scarcity, decision makers are likely to prioritize service options on the basis of perceptions of the people in need and the quality of services. In particular, policy makers are less likely to allocate money to people who seem to be responsible for their problems. Third, political ideology predicts some aspects of resource allocation. Discriminating decision makers as conservatives or liberals has been useful for explaining allocation decisions.

Prioritizing during times of scarcity

The overall availability of funds—and resource requests made for those funds—is a key factor influencing resource allocation. Decisions about resource allocation are fairly easy when the available funds exceed the demands on resources (8). Policy makers will fund all programs at the requested level. This seems to hold true whether policy makers are liberal or conservative. Unfortunately, government support rarely—if ever—exceeds the need for resources. Even in periods of economic prosperity, the government is deluged with budgetary requests. In this situation, individuals must distinguish the relative merit of competing programs and allocate resources accordingly. Prioritizing which groups should receive what resources is likely to be influenced by prejudice.

The effects of the perceived scarcity of funds is evidenced in survey research on public opinion about mental health parity (11). Contrary to notions of stigma, the public generally supports mental health parity in which benefits for psychiatric services parallel those for general medical disorders. The public welcomes insurance companies' provision of greater benefits to cover mental health services.

However, survey participants were not willing to increase their premiums to meet these added costs. Moreover, many of the participants were wary about changes to general medical benefits that result from parity. Thus, when endorsing more resources means threats to status quo benefits and resources, the public is more prejudiced. Social and political psychologists have shown that three sets of perceptions about the groups in need and the quality of programs serving these groups influence resource priorities.

Perceptions of personal need

A moral orientation to social relationships outlines the mutual obligations and assets that people share and becomes activated when there is disparity in these assets (12). One way in which this disparity is understood is in terms of need: the conditions that must be satisfied to minimize suffering (13). Policy makers are often confronted with programs that serve many people who have unmet needs, and they must determine who is experiencing the greatest hardship.

One way in which need has been prioritized in medical decision research has been in terms of survival (8). People are ranked as more needy when they have a disorder from which they are likely to die. Although suicide and violence are important concerns in mental health services, death is not an easy way to characterize need in this context. Instead, need might be framed at the individual level (in terms of how essential life functions such as independent work and housing are disrupted by serious mental illness) or at the cultural level (in terms of the loss of taxable income and the need for greater governmental support when persons who have psychiatric disabilities are not properly served).

Perceptions of program effectiveness

Allocation decisions are also influenced by perceptions of how well a program works. Decision makers prefer interventions that seem to be more effective (8). In part, this assessment is a further representation of a moral orientation and perceptions of personal need. Decision makers want to invest in services that will most efficiently minimize suffering. Moreover, perceptions of program effectiveness represent concerns about waste (13). Decision makers do not want to squander the limited amount of resources that support human services, in essence not being able to help another needy population because funds were allocated to a feckless program.

Perceptions of personal responsibility

Service programs are closely identified with the people they serve. Thus service populations that are viewed positively may yield greater resource allocations for corresponding programs (14). Personal responsibility has been shown to be an important mediator in these perceptions. Programs that serve people who are viewed as being responsible for their problems will probably be allocated fewer resources (2,8). Thus legislators who view people with psychiatric disabilities as responsible for their illness will be likely to divert funds away from mental health programs.

Research has shown that there are two components of responsibility attributions. The first component is internal versus external locus of control, and the second is perceptions about whether the causal event was controllable. Internally controlled events are viewed more harshly than externally controlled ones. Internal causality is perceived to be located within the individual (for example, the person is believed to be mentally ill because of poor character), whereas external loci reflect environmental impacts (for example, the person is believed to be mentally ill because of a head injury). Controllability is a function of perceived choice. Controllable events (the person chose mental illness rather than personal strength) are viewed more negatively than uncontrollable ones (the head injury resulted from a train crash).

Bernard Weiner (15) provided a comprehensive description of the attitudes, emotions, and behaviors related to responsibility attributions. According to Weiner, people who are experiencing events that are viewed as external and uncontrollable will be pitied by others and offered help. Government officials may be more likely to provide helpful resources to mental health programs when they pity people with mental illness, because their illness is viewed as uncontrollable. However, people whose life problems are viewed as internal and controllable are likely to evoke anger, which leads to punishment. Punishment, in the human services, has been viewed as coercive treatment and institutionalization. Consistent with Skitka's research, programs serving the former group are likely to be allocated greater resources than those serving people who have internal and controllable life problems.

Further research on responsibility judgments may suggest why mental health services are funded at lower levels than other programs. In one study, people described as having mental or behavioral problems were judged to be more responsible for their illnesses than those who had physical illnesses (16). A second study replicated this finding and also showed that people who had substance abuse and psychosis were viewed as more responsible for their problems than people who had physical illness or mental retardation (17). Research has also shown perceptions of personal responsibility to be the single greatest correlate of the values driving decisions about resource allocation (2) (Figure 1). Thus the public may be less likely to fund mental health programs.

Implications for educating policy makers

The research findings described here provide direction for education and advocacy programs that seek to affect the attitudes and behaviors of government officials, especially in terms of resource allocation. First, advocates must continue to educate legislators about issues of need by stressing priority areas—for example, adults and children who have serious mental illness and psychiatric disabilities. Need must also be defined by using relatively tangible terms—for example, needing to be hospitalized, being unable to work, and being unable to live alone. Second, research illustrating the importance of effectiveness perceptions supports the current effort to inform policy makers about evidence-based practices (1,18).

In particular, legislators and other government officials will be able to recognize programs worth funding—for example, assertive community treatment, supported employment, and family education and support (19,20,21)—as opposed to programs for which there is no evidence of impact, such as depth-oriented individual psychotherapy (22). Advocates need to find easy ways to communicate the complicated findings of evidence-based research so policy makers can discriminate among program requests. Effectiveness in general medicine is frequently described as how a specific treatment extends life—for example, completing pharmacological trial X for cancer can extend life by five years. Advocates need to find ways to translate the effectiveness of evidence-based treatments into similarly understandable parameters—for example, participating in psychiatric treatment Y can decrease hospitalization by two months, or completing rehabilitation program Z can increase full-time employment for a year.

Finally, advocacy programs need to address the issue of personal responsibility, especially given that research suggests that many members of the general public endorse the idea that people who have mental illness are responsible for their illness (16,17). Advocates need to help policy makers replace notions such as "people choose mental illness because of weak character" with more factual information such as "mental illness is caused by a personally uncontrollable brain disorder." In fact, one research study showed that research participants who were taught that people with mental illness are not responsible for their mental illness showed significant reductions in negative attitudes about and social distance toward mental illness (23). However, there may be a downside to this kind of information that needs to be sorted out in future research. Educating the public that individuals are not responsible for their mental illness might generalize to views that these individuals are incompetent and unable to take care of themselves (23). General incompetence is a separate stereotype that increases the stigma associated with mental illness (24).

Note that our discussion of education-based approaches has not included an alternative model for affecting resource allocation: the argument that more mental health programs, especially with mandatory treatment arms, need to be funded so that potentially dangerous people with mental illness do not commit criminal acts (25,26). The Treatment Advocacy Center, which now has programs in several states as well as national headquarters in New York City, has been a highly public promoter of highlighting the violence associated with untreated mental illness as a means for obtaining more resources. This kind of education program may be especially effective among conservative legislators who are more sensitive to public safety concerns (27).

However, appeals to dangerousness may lead to a limited kind of increase in resources: programs related to criminal justice and outpatient commitment may increase, whereas services related to independent work and housing may stagnate. Moreover, it might exacerbate another form of stereotype in the general population: that all people with mental illness are dangerous. Our group is in the midst of a study to examine the relative effects of education programs that focus on responsibility and dangerousness to sort out their effects on stigmatizing attitudes and on allocating money to mental health services.

Education programs are only one way in which to provide this information to legislators. Research suggests these programs can have significant effects on attitudes about mental illness (28). Even greater effects are found when contact is added to education programs. Significant changes are found in attitudes and behaviors when members of the general public meet people with mental illness (22,29). The effects of contact are even greater when participants hear the person's life story—both the troubles that result from psychiatric disabilities and the life successes that have resulted despite these disabilities—and have a chance to interact with the person about his or her story. One common phenomenon we have observed in these interactions is the "for real" effect (23): "Your life story seems too good be true; are you really mentally ill?" Research on contact suggests that advocacy programs may be more effective when they include people with mental illness in central positions of the education program.

Effect of political ideology

Research shows that conservatives and liberals react differently to the decision tree in Figure 1. Although political psychologists realize that the conservative-liberal dichotomy is complex, especially in the case of behaviors that are as multidetermined as public resource allocation, relatively simple definitions distinguishing the two have been used in research on resource allocation. Cognitive conservatism is a combination of political conservatism with personality measures of dogmatism, authoritarianism, and internal locus of control, whereas liberal humanism represents a mix of liberal ideals and the principled stage of moral development (30).

Consistent with the cognition-affect-behavior link discussed here, conservatives tend to experience angry emotions toward—and withhold resources from—programs that serve people who are viewed as being responsible for their problems (9). Thus conservative policy makers who view mental illness as internal and controllable are less likely to allocate resources to such services. Conservatives may be especially driven by a desire to punish violators of traditional norms (31): People who want to enjoy the benefits of society should behave responsibly or suffer the adverse consequences of their actions.

Liberals, on the other hand, are less likely to attribute controllable causes and to hold individuals responsible for their predicaments. However, when they do make such attributions they tend to remain sympathetic to the plight of these individuals and allocate available resources to relevant programs. Liberal attitudes and behaviors are affected by avoidance (32,33)—liberal policy makers prefer to sidestep situations in which priorities must be made and resources allocated. Liberals especially dislike placing a monetary value on human suffering and thus will show a decided preference for aiding everyone. In the absence of ample resources, liberals, like conservatives, will probably allocate resources to programs whose recipients are not perceived as being responsible for their predicaments (2,8).

The different ways in which liberals and conservatives approach allocation decisions provide further direction for how advocates might affect resource decisions. Presentations for a largely conservative audience should focus on information related to assumptions about personal controllability and subsequent punitiveness. For example, "People with mental illness do not choose their illness, they are not attempting to shirk their community responsibilities, and so they should not be punished by withholding funds for programs that will help them." Conversely, liberal audiences of decision makers should be encouraged to examine the avoidance issue: "Although there are several worthy human service programs to which government resources might be allocated, we need to choose mental health services now because the needs of this population are especially pressing."

Other factors to consider

The relevance of the factors in Figure 1 is all the more salient given variables that have, for the most part, not been shown to affect allocation decisions: equality, queue, and merit (8). From an equality perspective, all programs should have a similar chance of receiving funds (34). Policy makers would use a lottery or some other random process to assign priority according to equality. From a queue perspective, funding priority is based on where the program falls in terms of a waiting line—first come, first served. Although both these perspectives have an element of fairness, research has found that neither is predictive of allocation decisions (8). Moreover, the equality and queue perspectives ignore the political agendas that interact with resource allocations. Politicians would have to ignore contemporary history and the current exigencies of their constituency to assign resources on equality and queue principles.

Merit has similar problems. According to this perspective, resources should be allocated to programs that serve people who have made a contribution to their community. Thus mental health programs should be funded only if policy makers learn that people with psychiatric disability are of value to their community. Interestingly, the general public finds this kind of social Darwinism distasteful. Rating judgments about resource allocation on the basis of merit is as inappropriate as allocation based on a market in which resources go to the highest bidder (8).

What about accountability? One last factor that might be relevant to resource allocation was omitted from the decision tree in Figure 1: political accountability. Conventional wisdom suggests that politicians support programs when a large constituency will subsequently demand they justify their actions (35). For example, we assume that the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill and the National Mental Health Association have clout based on more than 200,000 members who will demand accountability of their government representatives. The effects of accountability may also be understood in terms of some of the social-cognitive variables in Figure 1 (36). Because space does not permit a comprehensive review of these factors here, we focus on four that may be especially useful in planning ways to reach out to local officials: presence, identifiability, evaluation, and the need to give reasons.

Decision makers are more responsive to constituencies when representatives are immediately present (37). This effect is especially pronounced when officials believe that their decisions and actions will be observed by their constituents. At the most direct level, this effect suggests that advocates have the greatest impact when they regularly meet with relevant government officials and when they are present at public meetings at which relevant information is being gathered. Decision makers are also more responsive to specific interest groups when their decision and actions are identifiable (38,39)—that is, when they believe that what they say or do in terms of specific resource allocations can be linked to them personally. Thus public information efforts that seek to pair legislators with specific policies will promote identification, especially when government officials are aware of these efforts.

Policy makers are likely to be responsive when they believe that allocation decisions will be evaluated (40,41). They are likely to act in an accountable manner when they believe that their performance is assessed by their constituents. Moreover, evaluation has a greater impact when it has consequences. Thus politicians who believe that citizens not only are educated about their actions but also will evaluate these actions and respond accordingly are likely to be responsive to a specific interest group.

Finally, research suggests that the need to give reasons influences politicians' behavior (42,43). Politicians are likely to be responsive to specific concerns when they believe that they will have to provide the reasons for what they say or do. Thus advocates need to attend public forums where they can query politicians about the rationale for specific decisions. This kind of immediate feedback is likely to direct attention to decisions about programs that are of interest to the advocates.

This discussion does not provide a complete summary of psychological variables that enhance accountability. However, it provides a flavor for the kind of information that social psychological research yields and that can inform and enhance public advocacy.

Conclusions

The goal of this article parallels the translational research agenda touted by the National Institute of Mental Health in the year 2000 (44)—namely, clinical and services research may be further advanced by adapting the theories and methods of basic behavioral research. To apply the wisdom of translational research to the goals of mental health advocates, we operationalize the decisions in which legislators and policy makers participate to allocate resources as largely social-cognitive phenomena. Basic social psychology research has shown that perceptions about specific services—and about the people receiving those services—significantly influence allocation decisions.

Moreover, these perceptions are influenced by the policy maker's political ideology and accountability. Most service researchers agree that clinical programs need to be informed by evidence. In this way, we are better assured that consumers will be offered interventions that are likely to have positive effects. In a similar manner, advocates should base their attempts to affect the behavior of policy makers on the basis of evidence. Extrapolating findings from social psychology, we listed several putative strategies that advocates might add to their armamentarium.

Most of the studies from which these factors were identified have been completed as decision-making paradigms on student populations in behavior-analog laboratories. Future research is needed to ensure that these paradigms are relevant to the experiences of the policy makers and legislators who must actually wrestle with these decisions. However, given the rigor and replication of earlier studies, these studies provide a useful heuristic for understanding the psychological factors that influence allocation decisions. This heuristic can guide future research in this area.

Finally, we need to remember that cognitive consideration of the social exigencies that affect resource allocation is only one aspect of the allocation decision. Government officials are also influenced by the economic and political demands of a specific decision. For example, legislators will frequently vote along party lines on appropriation decisions, irrespective of their individual concerns. Moreover, program administrators deciding how to allocate their budget to the component services in their program are influenced by the demands of the executive branch. Thus additional understanding of the behavior of decision makers will require partnering with economists, sociologists, and political scientists. This kind of complete picture of the public policy process will further inform advocates about their approach.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was partly supported by grant MH-62198 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the Chicago Consortium for Stigma Research. The authors thank Linda Skitka, Ph.D., for her helpful reviews of earlier drafts.

The authors are affiliated with the University of Chicago Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 7230 Arbor Drive, Tinley Park, Illinois 60477 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. A four-step priority-decision model of resource allocation for mental health servicesa

a Allocation decisions are affected by 1, scarcity of resources; 2, perception of need served by the program; 3, program effectiveness; and 4, perceived personal responsibility for illness. These four steps are further influenced by the political ideology of the decision maker. Adapted from Skitka and Tetlock (8,9)

1. Torrey EF, Zdanowicz M: Outpatient commitment: what, why, and for whom. Psychiatric Services 52:337-341, 2001Link, Google Scholar

2. Skitka LJ, Tetlock PE: Of ants and grasshoppers: the political psychology of allocating public assistance, in Psychological Perspectives on Justice: Theory and Applications. Cambridge Series on Judgment and Decision Making. Edited by Mellers B, Baron J. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1993Google Scholar

3. National Mental Health Association: Research Shows That Mental Health is Under Funded. Available at www.nmha.org/federal/appropriations/factsheet3.cfmsGoogle Scholar

4. National Expenditures for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment, 1997. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2000Google Scholar

5. Regier D, Narrow W, Rae D, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM, Dixon LB, et al: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11-20, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Davis J, Smith T: General Social Surveys, 1972-1998. Chicago, National Opinion Research Center, 1999Google Scholar

8. Skitka LJ, Tetlock PE: Allocating scarce resources: a contingency model of distributive justice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 28:33-37, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Skitka LJ, Tetlock PE: Providing public assistance: cognitive and motivational processes underlying liberal and conservative policy preferences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65:1205-1223, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Skitka LJ: Health care allocation priorities: locus-of-responsibility, scarcity, and cognitive style. Dissertation Abstracts International 50(10-B):4820-4821, 1990Google Scholar

11. Hanson KW: Public opinion and the mental health parity debate: lessons from the survey literature. Psychiatric Services 49:1059-1066, 1998Link, Google Scholar

12. Deutsch M: Interdependence and psychological orientation, in Cooperation and Helping Behavior: Theories and Research. Edited by Derlega V, Grzelak JL. New York, Academic, 1982Google Scholar

13. Greenberg J: The justice of distributing scarce and abundant resources, in The Justice Motive in Social Psychology. Edited by Lerner MJ, Lerner SC. New York, Plenum, 1981Google Scholar

14. Committee on Addictions of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry: Responsibility and choice in addiction. Psychiatric Services 53:707-713, 2002Link, Google Scholar

15. Weiner B: Judgments of Responsibility: A Foundation for a Theory of Social Conduct. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

16. Weiner B, Perry R, Magnusson J: An attributional analysis of reactions to stigma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55:738-748, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, et al: Predictors of participation in campaigns against mental illness stigma. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:378-380, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Corrigan PW, Steiner L, McCracken SG, et al: Strategies for disseminating evidence-based practices to staff who treat people with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 52:1598-1606, 2001Link, Google Scholar

19. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313-322, 2001Link, Google Scholar

20. Drake RE, Goldman HE, Leff HS, et al: Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services 52:179-182, 2001Link, Google Scholar

21. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:903-911, 2001Link, Google Scholar

22. Corrigan P, Rowan D, Green A, et al: Challenging two mental illness stigmas: personal responsibility and dangerousness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 28:293-310, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Corrigan P, Lundin R: Don't Call Me Nuts! Coping With the Stigma of Mental Illness. Tinley Park, Ill, Recovery Press, 2001Google Scholar

24. Corrigan PW, Backs AE, Green A, et al: Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:219-225, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Jaffe DJ: Remarks on assisted outpatient treatment. Presented at the annual conference of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, Chicago, Ill, June 30, 1999Google Scholar

26. Jaffe DJ, Zdanowicz, MT: Federal neglect of the mentally ill. Washington Post, Dec 30, 1999, A31Google Scholar

27. Altemeyer B: The Authoritarian Specter. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

28. Penn DL, Corrigan PW: Social cognition in schizophrenia: answered and unanswered questions, in Social Cognition and Schizophrenia. Edited by Corrigan PW, Penn DL. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2001Google Scholar

29. Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, et al: Three strategies for changing attributions about severe mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:187-195, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Carroll JS, Perkowitz WT, Lurigio AJ, et al: Sentencing goals, causal attributions, ideology, and personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52:107-118, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Altemeyer B: Enemies of Freedom: Understanding Right-Wing Authoritarianism. San Francisco, Calif, Jossey-Bass, 1988Google Scholar

32. Tetlock PE: A value pluralism model of ideological reasoning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50:819-827, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Tetlock PE, Skitka L, Boettger R: Social and cognitive strategies for coping with accountability: conformity, complexity, and bolstering. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57:632-640, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Deutsch M: Equity, equality, and need: what determines which value will be used as the basis of distributive justice? Journal of Social Issues 31:137-149, 1975Google Scholar

35. Tetlock PE: Good judgment in international politics: three psychological perspectives. Political Psychology 13:517-539, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

36. Lerner JS, Tetlock PE: Accounting for the effects of accountability. Psychological Bulletin 125:255-275, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Guerin B: Social Facilitation. New York, Cambridge University Press, 1993Google Scholar

38. Reicher S, Levine M: Deindividuation, power relations between groups and the expression of social identity: the effects of visibility to the out-group. British Journal of Social Psychology 33:145-163, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Schopler J, Insko CA, Drigotas SM, et al: The role of identifiability in the reduction of interindividual-intergroup discontinuity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 31:553-574, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

40. Guerin B: Reducing evaluation effects in mere presence. Journal of Social Psychology 129:183-190, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

41. Sanna LJ, Turley KJ, Mark MM: Expected evaluation, goals, and performance: mood as input. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22:323-335, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

42. Simonson I, Nowlis SM: The role of explanations and need for uniqueness in consumer decision making: unconventional choices based on reasons. Journal of Consumer Research 27:49-68, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

43. Wilson TD, LaFleur SJ: Knowing what you'll do: effects of analyzing reasons on self-prediction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68:21-35, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Translating Behavioral Science Into Action. Pub (NIH) 00-4699. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 2000Google Scholar