Use of Substance Abuse Treatment Services by Persons With Mental Health and Substance Use Problems

Abstract

OBJECTIVES: This study provided population estimates of mental syndromes and substance use problems and examined whether the co-occurrence of mental health and substance use problems was associated with the use of substance abuse treatment services. METHODS: Study data were drawn from the 1997 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. RESULTS: Of the total sample of 16,661 adults, 2 percent reported using services for alcohol or drug use problems in the previous year. Among the 3,474 (17 percent) who reported at least one alcohol or drug use problem, 6 percent used substance abuse services. Only 4 percent of persons who reported substance use problems alone received any substance abuse treatment service in the previous year. Only 3 percent of persons who reported alcohol use problems alone received such services. Among persons with one or more substance use problems, the prevalence of service use was 11 percent among persons who reported one co-occurring mental syndrome and 18 percent among those who reported two or more mental syndromes. Multiple logistic regression analyses identified a number of subgroups who might have needed substance abuse services but did not receive them, including women, Asians and Pacific Islanders, college graduates, persons employed full-time, persons who abused alcohol only, and persons with substance use problems who reported no coexisting mental syndromes. CONCLUSIONS: The rate of help seeking among persons with alcohol use problems is low, which is a public health concern.

A substantial number of Americans suffer from a mental health or substance use disorder, and a large proportion have comorbid disorders. Nearly 50 percent of respondents to the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) reported at least one lifetime psychiatric disorder, and close to 30 percent reported at least one disorder in the previous year (1). An estimated 79 percent of the NCS respondents who reported a lifetime disorder reported co-occurring disorders—either co-occurring mental disorders or a mental disorder and a co-occurring substance use disorder (1). Substance abuse or dependence is often associated with mood or anxiety disorders (2,3,4,5,6,7).

The literature also suggests substantial barriers to mental health or substance abuse treatment (2,8,9). The National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area (NIMH-ECA) study found that 84 percent of persons with a six-month psychiatric disorder had not received treatment from general medical or mental health care providers during the previous six months (8). Similarly, the NCS reported that about 83 percent of persons with a past-year disorder received no mental health or substance abuse services from either general medical or mental health care providers in the previous year (10).

Persons with panic disorder are the most likely to receive mental health services, and those with substance use disorders or phobias are the least likely to receive services (10,11,12). Of persons with substance dependence, greater use of mental health services was noted among those with drug dependence than among those with alcohol dependence (10). The co-occurrence of mental health and substance use disorders has been reported to increase rates of use of mental health services (2,3,4,9,13).

Population-based studies have tended to focus on the use of mental health services among persons with a psychiatric diagnosis. In this study, we capitalized on data from a recent national survey to determine population estimates of co-occurring mental syndromes and substance use problems and the use of substance abuse services and to examine correlates of service use. We were particularly interested in the extent to which the co-occurrence of mental syndromes and substance use problems was associated with the use of substance abuse services.

Methods

Sample

Data for the study were drawn from the 1997 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) (14). The NHSDA is designed primarily to provide national estimates of the use of illicit drugs, alcohol, and tobacco by the U.S. civilian, noninstitutionalized population. Targeted populations include household residents, residents of noninstitutional group residences—for example, college dormitories, group homes, homeless shelters, and rooming houses—and civilians dwelling on military installations (15).

Persons aged 12 years or older were selected for participation in the 1997 survey on the basis of multistage area probability sampling. A total of 24,505 individuals completed one-hour interviews in their homes, which represented a response rate of 78 percent. Other details of the survey design and data collection procedures are reported elsewhere (14). Our study focused on adults (persons aged 18 years or older) (unweighted N=16,661), because the 1997 NHSDA did not include mental health questions in the instrument administered to adolescents.

Definitions of variables

We examined past-year prevalence of substance use problems, mental syndromes, and use of both mental health and substance abuse services. Of the seven criteria for substance dependence specified by DSM-IV (16), six were assessed in the 1997 NHSDA: tolerance; using a given substance in larger amounts than intended; inability to cut down on or stop using the substance; spending a great deal of time getting the substance; reducing important social, occupational, or recreational activity because of substance use; and manifesting health or psychological problems because of substance use.

In this article, the term "alcohol use problems" means meeting one or more of six DSM-IV alcohol dependence criteria in the past year. "Drug use problems" means meeting one or more of six DSM-IV drug dependence criteria resulting from the nonmedical use of any of the following drugs in the previous year: cocaine or crack, marijuana, inhalants, heroin, hallucinogens, pain relievers, stimulants, and pain relievers.

The 1997 NHSDA assessed the presence of four mental syndromes in the previous year: depression, panic attack, agoraphobia, and generalized anxiety syndrome (17,18). Definitions for each self-reported disorder were designed to operationalize the criteria from the DSM-III-R diagnosis (17). In brief, depression was measured by using 27 items that asked respondents to report whether they felt either sad or depressed or experienced a loss of interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities for most of the day over a two-week period. Panic attack (eight items) was defined as a discrete episode of intense fear or discomfort with at least four accompanying symptoms. Agoraphobia (seven items) was defined as unreasonably strong fears about being in places or situations in which most people would not be afraid. Generalized anxiety syndrome (11 items) was defined as having unrealistic or excessive anxiety about two or more life circumstances for at least six months.

Substance abuse service use was defined broadly as receipt of any service for alcohol or illicit drug use at any location in the previous year—in a hospital, drug or alcohol rehabilitation facility, mental health center or facility, private doctor's office, prison or jail, or self-help group. Mental health service use was defined narrowly as receipt of treatment in the previous year for psychological or emotional problems at a mental health clinic, in a hospital, or by a mental health professional in an outpatient setting.

Social and demographic variables studied included gender, race or ethnicity, age, education, employment status, and marital status. Four categories of employment status were defined (14): full-time, (at least 35 hours a week), part-time (fewer than 35 hours a week), unemployed, and other (for persons who were retired, disabled, homemakers, or students).

Data analyses

Because the study data were obtained through a multistage probability sampling design, SUDAAN software (19), which applies a Taylor series linearization method to account for complex design features of the NHSDA, was used for weighted statistical analyses. Weighted estimates of mental syndromes and substance use problems were based on the entire sample of 16,661 adult respondents. Estimates of substance abuse service use were based on a subsample of 3,474 respondents who reported at least one DSM-IV alcohol or drug use problem in the previous year. Odds ratios were used to describe correlates of this population and to denote the relative odds of service use as a function of the covariates examined in the model.

Results

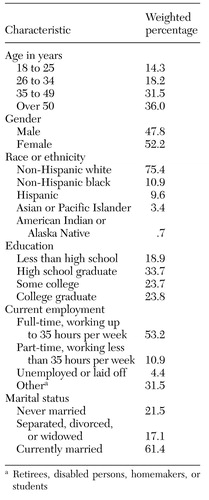

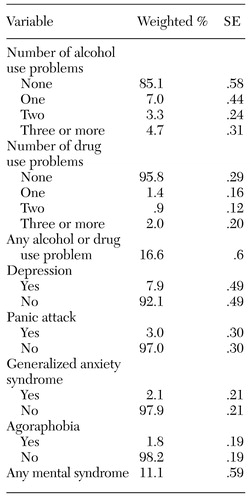

The demographic characteristics of the 16,661 adults in the 1997 NHSDA sample are summarized in Table 1. Prevalence estimates of mental syndromes and substance use problems are given in Table 2. Approximately 15 percent of all adults reported at least one alcohol use problem, and 4 percent reported at least one drug use problem. Altogether, 3,474 (17 percent) reported at least one alcohol or drug use problem in the year before the survey. Close to 2 percent of the respondents—or 6 percent of those who had at least one alcohol or drug use problem—reported receiving any substance abuse service for their use of alcohol or illicit drugs in any setting in the previous year. Only .8 percent of those with no substance use problems received such services in the previous year.

Overall, 1,929 respondents (11 percent) reported at least one of the four mental syndromes in the previous year. The syndrome with the highest prevalence was depression (8 percent). Close to 5 percent of all respondents, or 23 percent of those with at least one mental syndrome, reported receiving treatment from specialty sectors for mental health problems in the previous year.

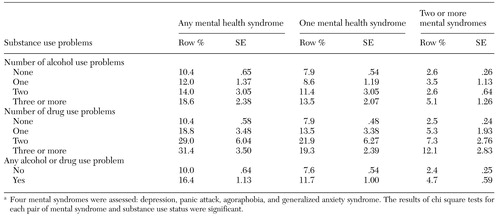

One-year prevalence estimates of mental syndrome by substance use status are shown in Table 3. Significantly higher rates of mental syndromes were noted among persons who reported any substance use problems than among those who reported no problems; those who reported at least three substance use problems were particularly likely to report a mental syndrome. For example, 10 percent of persons with no alcohol use problem reported having at least one mental syndrome, compared with almost 19 percent of those with at least three alcohol use problems. Similarly, one in ten persons with no use drug use problems reported having at least one mental syndrome, compared with about three in ten who had at least three drug use problems.

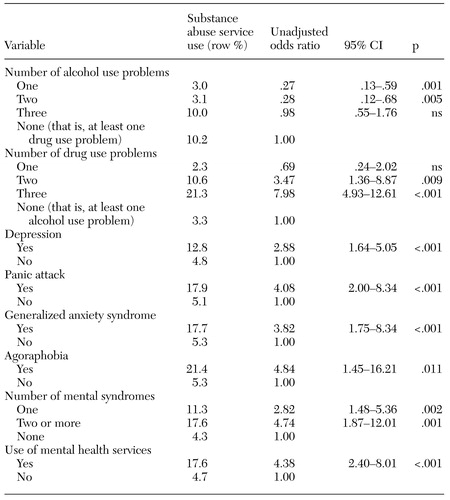

Prevalence estimates of substance abuse service use among adults with at least one alcohol or drug use problem are given in Table 4. Significant bivariate associations were observed between use of substance abuse services and each of the variables related to alcohol or illicit drug use problems, mental syndromes, and past-year use of mental health services. Persons who reported three or more drug use problems were much more likely to use substance abuse services than those who reported fewer or no problems. A very low prevalence of service use (3 percent) was noted for respondents who reported having alcohol use problems only.

The co-occurrence of mental syndromes and substance use problems proved to be highly associated with help-seeking behavior; 13 percent of substance-abusing respondents who reported depression used substance abuse treatment services, compared with 5 percent who did not report depression. Similarly, co-occurring panic attack and the presence of generalized anxiety syndrome and agoraphobia were each strongly associated with higher rates of substance abuse service use among substance-abusing persons. The number of mental syndromes reported by individual respondents was also strongly associated with use of substance abuse services. In addition, persons with substance abuse who recently received treatment for mental health problems were much more likely to use substance abuse services during the same one-year period.

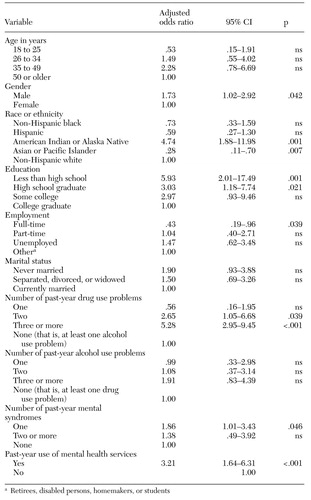

The final logistic regression model assessed whether the association between use of substance abuse treatment services and mental health and substance use variables was independent of demographic characteristics. The results are summarized in Table 5. The model included significant correlates found in the bivariate analysis—race or ethnicity, educational level, employment status, and marital status—as well as age, gender, alcohol or drug use problems, mental syndromes, and use of mental health services.

This adjusted model showed that men were twice as likely as women to seek services. Compared with white persons, American Indians and Alaska Natives were much more likely and Asians and Pacific Islanders were much less likely to use substance abuse services. Level of education was strongly and inversely associated with service use. Persons with substance use problems who worked full-time were much less likely to use services than those who did not work full-time. Neither age nor marital status was related to service use.

With statistical adjustment for these specified demographic characteristics, the reported number of drug use problems (but not alcohol use problems) was strongly associated with service use. Again, recent use of mental health services was strongly associated with use of substance abuse services. Persons who reported one coexisting mental syndrome were about two times as likely to seek substance abuse services as those who did not report a coexisting syndrome.

Discussion and conclusions

We examined the co-occurring mental syndromes and substance use problems and factors related to the use of substance abuse treatment services in a national sample of adults. We found that 9 percent and 4 percent reported at least one DSM-IV alcohol or drug use problem, respectively, in the previous year. Overall, 11 percent of the respondents reported at least one of the four NHSDA-specified mental syndromes in the previous year—depression, panic attack, agoraphobia, or generalized anxiety syndrome. Approximately one-third of respondents who had at least three drug use problems also reported at least one mental syndrome during a one-year period. Almost one-fifth of respondents who had at least three alcohol use problems also reported at least one mental syndrome.

The use of substance abuse treatment services among persons with one or more coexisting mental syndromes was estimated at 16 percent, whereas only 4 percent of those without a coexisting mental syndrome received services. Adjusted logistic regression analyses of data from respondents who reported at least one alcohol or drug use problem indicated that the use of substance abuse treatment services was associated with the presence of drug use problems (but not alcohol use problems), coexisting mental syndromes, and recent use of mental health treatment services.

The study design had some limitations. First, the NHSDA uses a cross-sectional design, so causality cannot be inferred. Our analyses were based on self-reported data, which may be affected by recall bias, memory errors, and respondents' reluctance to answer sensitive questions. Both mental health and substance use problems may have been underreported. Second, the sampling frame of the NHSDA is limited to civilian, noninstitutionalized persons. Higher rates of drug use have been observed among homeless persons and individuals living in institutional group quarters (20).

Third, assessments of self-reported mental syndromes were restricted to the four syndromes specified in the NHSDA. Fourth, the lack of assessments related to the withdrawal criterion for substance dependence is likely to have underestimated substance use problems, particularly the prevalence of alcohol dependence—that is, persons who reported three or more symptoms of dependence. Although withdrawal is one of the specified criteria for the DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol dependence, the diagnosis of marijuana dependence does not specify the presence of withdrawal (16), the most common illicit drug of dependence in the general population (21). Nevertheless, our focus on self-reported substance use problems as defined by DSM-IV may have missed some persons with substance use problems who needed services but who reported no problem, perhaps denying that they had a substance use problem or believing that their substance use was under control (22).

Finally, the survey questions that tapped use of substance abuse treatment services cast a much wider net than those that assessed mental health treatment. For example, substance abuse services included self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, and other social services, whereas mental health services were restricted to services delivered by specialty providers. Because of this broad definition of substance abuse services, our estimates of substance abuse service use are based on adults who reported one or more alcohol or drug use problems. Our analyses might also have identified some subgroups who did not perceive the need for such services. Nevertheless, these estimates of co-occurrence represent an advance over those based on clinical samples, which may yield inflated estimates given that persons who have multiple ailments are more likely to seek treatment (23).

Perhaps the most salient finding of this study concerns the proportion of adults in the general population who reported at least one DSM-IV substance use problem—almost one in six—and the very small number of them who received any substance abuse service. This finding must be tempered with the recognition that the presence of a solitary problem may not constitute sufficient reason for seeking help. On the other hand, the definition of substance abuse services as operationalized by the NHSDA is sufficiently wide to capture a variety of nonclinical settings, including self-help groups.

This finding thus speaks convincingly to the need for primary health care providers or family physicians to conduct routine screenings for substance use problems, to make referrals to prevention or treatment specialists as appropriate, and to follow up on these referrals and their effects on subsequent visits. The finding also suggests that purchasers of health services in the public and private sectors who are truly interested in the well-being of those covered by their policies should induce the managed care organizations with which they do business to support these practices.

Our results also indicate that some subgroups may need substance abuse services but not receive them, including women, Asians and Pacific Islanders, college graduates, persons who are employed full-time, persons with alcohol abuse only, and persons with substance abuse who report no coexisting mental syndromes. These findings suggest that these subgroups should be targeted by prevention specialists' outreach efforts. More research is needed to examine the nature and extent of barriers to substance abuse treatment.

Also of interest is the much lower use of substance abuse services by substance abusers who did not report a mental syndrome or use of mental health services. This finding, which is similar to that reported by the NIMH-ECA (3) and others (9,24), suggests that help-seeking behavior may be less stigmatized for persons with mental health syndromes than for those with substance use problems alone. It is also possible that, relative to substance abuse services, mental health services are more available or more easily reimbursed. We may also conjecture that persons with a dual diagnosis may be more in need of services than those with a substance use disorder alone, because their substance abuse may be more severe or may be exacerbated by mental illness (25).

It is also possible that persons with substance use problems who seek or receive services are—or become—more aware of their mental health problems and thus are more likely to report them retrospectively. If this hypothesis is correct, receipt of substance abuse services may tend to generate a dual diagnosis even among persons with discrete substance use or mental disorders (26). Of course, outside of a prospective study, the causal relationships between substance use and mental health problems and the processes by which an understanding of one may lead to recognition of the other cannot be disentangled (26).

Overall, our findings indicate that the severity of substance use problems plays a significant role in help seeking. It appears that many persons with substance use problems received no help until multiple substance use or other mental health problems affected their daily life. Delaying help seeking might have a negative impact on the course of substance abuse or might lead to the development or exacerbation of a comorbid mental disorder and increase health care costs. If behavioral health care systems were designed to increase access to early prevention and treatment interventions for persons with substance use problems, the rate of comorbidity and the cost of treating problems related to substance use might be lower.

The results of this study have several additional implications. First, the nature and pathways to use of alcohol treatment services deserve more focused investigation. Although alcohol use problems are more prevalent than other drug use problems, persons with an alcohol use problem alone were not likely to use substance abuse services. Because of societal sanctions and cultural norms of alcohol use, some adults with alcohol use problems might not perceive their alcohol use behaviors as problematic. Studies need to identify factors that enhance or impede the likelihood of service use, particularly among the underserved populations we identified. Some of these factors may be related to specific cultural or gender issues, whereas others may be linked to perceived stigma, attitudes toward treatment services, service availability, costs, and accessibility.

Second, primary health care and prevention providers should also be aware that persons with substance use problems who do not also report or manifest mental problems may be less visible and thus more likely to be undetected and underserved. Primary health care providers should be trained to detect substance use problems and refer patients with these problems to appropriate services. Finally, our findings suggest the need to develop and implement strategies to increase the use of treatment services among persons with substance use problems.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by contract 282-98-0022 from the office of managed care of the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The authors thank Nancy J. Kennedy, Dr.P.H.

Dr. Wu is affiliated with the Center for Risk Behavior and Mental Health Research of Research Triangle Institute, P.O. Box 12194, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709-2194 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Ringwalt is with the Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Dr. Williams is with the office of managed care of the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention in Rockville, Maryland.

|

Table 1. Social and demographic characteristics of all adults in the 1997 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (unweighted N=16,661)

|

Table 2. One-year prevalence estimates of substance use and mental health problems among adults in the 1997 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (unweighted N=16,661)

|

Table 3. One-year prevalence estimates of mental syndromes among adults by substance use status in the 1997 National Household Survey on Drug Abusea

a Four mental syndromes were assessed: depression, panic attack, agoraphobia, and generalized anxiety syndrome. The results of chi square tests for each pair of mental syndrome and substance use status were significant.

|

Table 4. One-year prevalence estimates of substance abuse service use among adults with at least one alcohol or drug use problem in the 1997 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (unweighted N=3,474)

|

Table 5. Adjusted odds ratios in the final multiple logistic regression model of substance abuse service use among adults with at least one alcohol or drug use problem (unweighted N=3,474)

1. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17-31, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Helzer JE, Pryzbeck TR: The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 49:219-224, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Grant BF, Harford TC: Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression: results of a national survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 39:197-206, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, et al: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:313-321, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Merikangas KR, Mehta RL, Molnar BE, et al: Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addictive Behaviors 23:893-907, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Regier DA, Shapiro S, Kessler LG, et al: Epidemiology and health service resource allocation policy for alcohol, drug abuse, and mental disorders. Public Health Reports 99:483-492, 1984Medline, Google Scholar

9. Wu LT, Kouzis AC, Leaf PJ: Influence of comorbid alcohol and psychiatric disorders on utilization of mental health services in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1230-1236, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, et al: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:115-123, 1999Link, Google Scholar

11. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Olfson M, Kessler RC, Berglund PA, et al: Psychiatric disorder onset and first treatment contact in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1415-1422, 1998Link, Google Scholar

13. Bourdon KH, Rae DS, Locke BZ, et al: Estimating the prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adults from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area Survey. Public Health Reports 107:663-668, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

14. Office of Applied Studies: National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Main Findings 1997. DHHS pub (SMA) 99-3295. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1999Google Scholar

15. Office of Applied Studies: National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population Estimates 1997. DHHS pub (SMA) 98-3250. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998Google Scholar

16. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

17. Mental Health Estimates From the 1994 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. DHHS pub (SMA) 96-3103. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1996Google Scholar

18. Substance Use Among Women in the United States. DHHS pub (SMA) 97-3162. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1997Google Scholar

19. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS: SUDAAN software for the statistical analysis of correlated data. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1996Google Scholar

20. Preliminary Results From the 1996 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. DHHS pub (SMA) 97-3149. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1997Google Scholar

21. Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC: Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology 2:244-268, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ: Contrast of treatment-seeking and untreated cocaine abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry 49:464-471, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Berkson J: Limitations of the application of the 4-fold table analyses to hospital data. Biometrics 2:47-53, 1946Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Galbaud du Fort G, Newman SC, Bland RC: Psychiatric comorbidity and treatment seeking: sources of selection bias in the study of clinical populations. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:467-474, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Hanna EZ, Grant BF: Gender differences in DSM-IV alcohol use disorders and major depression as distributed in the general population: clinical implications. Comprehensive Psychiatry 38:202-212, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Schuckit MA: Genetic and clinical implications of alcoholism and affective disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:140-147, 1986Link, Google Scholar