Patterns of Service Use Among Persons With Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed 12-month service use patterns among people with psychotic disorders and sought to identify determinants of service use. METHODS: As part of a large two-phase Australian study of psychotic disorders, structured interviews were conducted with a stratified random sample of adults who screened positive for psychosis. Demographic characteristics, social functioning, symptoms, mental health diagnoses, and use of psychiatric and nonpsychiatric services were assessed. Data were analyzed for 858 persons who had an ICD-10 diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and who had been hospitalized for less than six months during the previous year. RESULTS: People with psychotic disorders had high levels of use of health services, both in absolute terms and relative to people with nonpsychotic disorders. Those with psychotic disorders were estimated to have an average of one contact with health services per week. Use of psychiatric inpatient services was associated with parenthood, higher symptom levels, recent attempts at suicide or self-harm, personal disability, medication status, and frequency of alcohol consumption. Services provided by general practitioners (family physicians) were more likely to be obtained by older people, women, people with greater availability of friends, those with fewer negative symptoms, and those whose service needs were unmet by other sources. People who were high users of health services also reported having more contact with a range of non-health agencies. CONCLUSIONS: The predictors of service use accounted for small proportions of the variance in overall use of health services. The role of general practitioners in providing and monitoring treatment programs and other psychosocial interventions needs to be acknowledged and enhanced.

Information about patterns of service use among people with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders is important for planning mental health services and allocating resources. The shift in emphasis to community care as a result of deinstitutionalization has broadened the forms and locations of treatments offered. Health care planners are now turning their attention to the determinants of service use in various settings. Potential predictors of the extent of service use include demographic factors, diagnosis, patterns of comorbidity (especially substance use), and disability.

Several sociodemographic factors have been associated with higher hospital admission and readmission rates, such as being younger (1,2,3); being single, divorced, or widowed (2); being unemployed (4); being socially disadvantaged (5); living in an urban area (5); having inadequate access to aftercare (6,7); and having a comorbid substance use disorder (8). Factors associated with multiple readmissions include the number of previous admissions, longer inpatient stay, and a diagnosis of psychosis (9,10,11). Some patients seem to need long and frequent admissions despite the expansion of community care (6).

In a three-year follow-up study in Finland of 537 new patients, 5 percent of the cohort met the criteria for "revolving-door" patients, and readmission rates were higher among patients who had psychosis and personality disorder (12). Two percent of the cohort became long-stay hospital patients, and this outcome was predicted by psychiatric diagnosis. Patients who continue to require hospitalization despite the availability of community services deserve attention, because they make considerable demands on psychiatric resources and personnel and their care is expensive, not only in terms of hospital beds occupied but also in terms of sickness benefits and disability pensions.

Lifetime comorbid substance abuse occurs among a large proportion of people with severe mental illness (13). A study that measured the use and cost of institutional and outpatient services in three groups of patients with schizophrenia—those with current substance abuse, those with past substance abuse, and those without a history of substance abuse—showed that the use and cost of institutional (hospital and jail) services were significantly higher for patients with current substance abuse (14). The patients with current substance abuse also used more emergency services. The co-occurrence of psychiatric illness and an alcohol use disorder has been found to be a stronger predictor of service use than either disorder alone (15). Most research has not taken into account the effect on service use of other patterns of comorbidity and the heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders (15).

In one study, the nature of the affective episode and whether the person had a history of childhood physical abuse were significant predictors of mental health service use among persons with bipolar disorder (16). The authors of that study proposed that service use depends on multiple patient and system factors rather than simply being a passively driven function of disease severity (16). For example, patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who live alone or in marginal accommodation seek more inpatient or day care services than those who live with an informal caregiver (17). It may also be useful to examine the predictors of service use by people who have a psychotic disorder within the framework of a generic model of health service use, such as Andersen's model, which incorporates the effects of predisposing, enabling, and need factors (18,19).

Thus it is clear that several variables may be involved in determining the pattern and extent of service use among persons with mental illness. We present data from a large multicenter study of people with psychotic disorders that was conducted in Australia in 1997-98, known as the Low Prevalence (psychotic) Disorders Study (LPDS) (20). Detailed information about service use was collected from the respondents, along with demographic data, information on symptoms and mental state that enabled psychiatric and substance use diagnoses to be made, and assessment of levels of disability. The aims of this study were to provide a comprehensive description of service use among persons with psychotic disorders and to identify the main determinants of service use. Many of the service use variables measured in the LPDS were amenable to being categorized as predisposing factors (for example, demographic details and premorbid functioning), enabling factors (family and social support, employment, and welfare status), or need factors (diagnosis, symptoms, and disability) as identified in Andersen's model (18,19). We subsequently used this approach to assess the predictors of service use.

Methods

Study sample

A detailed account of the design and methods for the LPDS has been provided by Jablensky and colleagues (21). This two-phase, census-based study was conducted in four metropolitan areas in Australia in 1997-98. The inclusion criteria were age of 18 to 64 years and an ICD-10 diagnosis of any nonorganic or non-substance-induced psychotic disorder. Phase 1 comprised a one-month census of all persons who had been in contact with mainstream mental health services in the four participating areas. This sample was supplemented by patients drawn from the caseloads of general practitioners or private psychiatrists in the participating areas, persons with no fixed abode or living in marginal accommodation, and persons who had had previous service contacts but who were not in contact with the services during the census month.

All eligible participants were screened for psychosis by using the method described by Jablensky and colleagues (21). Phase 2 comprised standardized interviews with a stratified random sample of 980 individuals who screened positive for psychosis. Exclusion criteria were status as a temporary visitor to Australia, significant cognitive deficit, residence in a nursing home or prison, and inability to communicate adequately in English. Approval was obtained from relevant institutional ethics committees, and the participants gave informed consent before being interviewed.

Measures

The postscreening assessment instrument was the Diagnostic Interview for Psychosis (DIP), a semistructured diagnostic interview with three modules: demographic and social functioning, including selected items from the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (DAS) (22); diagnosis using the Operational Criteria for Psychosis (OPCRIT) (23) and elements of the WHO Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) (24); and reported use of a range of hospital- and community-based services in the previous year. Interviews were conducted by trained clinical interviewers, and interrater diagnostic agreement was satisfactory (generalized kappa=.73 for ICD-10 diagnoses).

The main health service use variables were inpatient psychiatric and nonpsychiatric hospitalization; outpatient psychiatric and nonpsychiatric services, including attendance at hospital and community clinics or home visits from a community mental health team; and psychiatric and nonpsychiatric emergency service contacts, including use of community-based crisis teams. Use of psychiatric rehabilitation services and consultations with general practitioners (family physicians) were also recorded.

The proportions of participants who had used these services in the previous year were calculated, and the extent of use by those who had used services was measured. Extent of use was measured in weeks for inpatient hospitalization and in the number of contacts for all other variables. Because the units of measurement varied and because the episodes of service delivery were not discrete (for example, emergency service contacts resulting in hospital admissions on the same day), combining the various components of health service use was problematic. Nevertheless, an overall index of estimated health service contacts was constructed by treating all reported contacts as discrete events or days, including counting each day in the hospital as a separate event. All service use information was based on patient self-report, which has acceptable levels of reliability (25), and a number of checks to minimize the potential effects of any recall inaccuracies were built into the interviews (20).

Three measures of disability were derived from the interview data. First, two disability scales were constructed on the basis of item loadings from a principal-components analysis of the DAS (22): a personal disability score, which covered five DAS items (participation in household activities, interests, self-care, occupational performance, and overall socializing), and a social disability score, which included three DAS items (intimate relationships, deterioration in relationships, and social withdrawal). Second, we regrouped global ratings from the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) (26). Social support was assessed in two ways: the extent of contact with family members, excluding children, and the availability of friends. Most items measuring disability in the LPDS had good to excellent reliability (27).

The DIP items covering current symptoms and mental state as well as past-year symptoms were subjected to a principal-components analysis to confirm their patterns of association. Scores on four symptom factors were derived on the basis of item loadings: depression, mania, reality distortion, and disorganization. To facilitate comparisons with other studies, a negative symptom score was derived by grouping three items that would have otherwise been included in the disorganization factor.

Data analysis

Chi square tests were used for simple group comparisons involving categorical outcome variables; one-way analysis of variance was used for continuous outcome variables. Hierarchical logistic regressions were used to identify significant predictors of the likelihood of 12-month service use; odds ratios (ORs) were the preferred metric for reporting the magnitude of effects. Hierarchical regressions were also used to examine predictors of the extent of 12-month service use by those who used services; partial correlations (pr) were the preferred metric for reporting the contribution of individual predictors. Where appropriate—for example, for defined sets of analyses—Bonferroni-adjusted probabilities were used to control for the number of outcome variables. For the remaining analyses, the threshold for significance was set at .01 as a partial control for the number of tests.

Results

Sample characteristics

The 980 participants interviewed for the LPDS included 44 (4.55 percent) who did not meet ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder, three (.03 percent) with poorly completed service use data, and a further 75 (7.7 percent) who reported that they had been hospitalized for more than six months during the previous year. These individuals were excluded from the analyses, because we were interested primarily in patterns of service use among persons with psychosis and because the long-stay patients would have had fewer opportunities to use the full range of services. The resulting data set included 858 participants, 516 men (60.1 percent) and 342 women (39.9 percent), with a mean±SD age of 39.19±11.79 years. Five ICD-10 diagnostic groups were identified: schizophrenia (445 patients, or 51.9 percent), schizoaffective disorder (95 patients, or 11.1 percent), bipolar disorder or mania (111 patients, or 12.9 percent), depressive psychosis (66 patients, or 7.7 percent), and other psychosis (141 patients, or 16.4 percent).

Overall service use

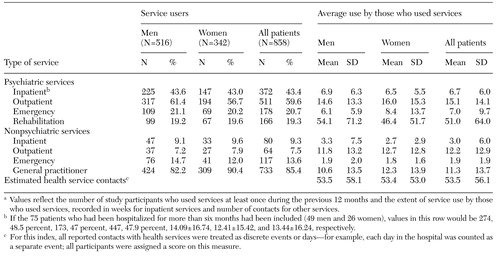

Twelve-month use of health services is shown by sex in Table 1. About a fifth of the sample (21.9 percent) reported that they had not used any psychiatric services during the year, and 11.7 percent had not used any nonpsychiatric services. The only significant difference between men and women was in the overall use of general practitioner services: women were more likely than men to have had at least one consultation during the year (90.4 percent compared with 82.2 percent, χ2= 11.06, df=1, p<.001).

The overall likelihood of at least one service contact was highest for visits to general practitioners (85.4 percent), followed by psychiatric outpatient services (59.6 percent) and psychiatric inpatient services (43.4 percent). On average, users of these services had 11.3 general practitioner consultations, 15.1 psychiatric outpatient contacts, and 6.7 weeks in psychiatric inpatient facilities. Of the 418 study participants (48.7 percent) who had at least one hospital admission during the previous year, 338 (80.9 percent) had admissions only to inpatient psychiatric services. This latter group had an average of 2.2±2.8 admissions and 6.7±6 weeks in the hospital, for an average reported length of stay (per episode) of about three weeks. Our overall index of estimated health service contacts indicated an average of 53.5 contacts, or about one day per person per week; the rates were similar for men and women.

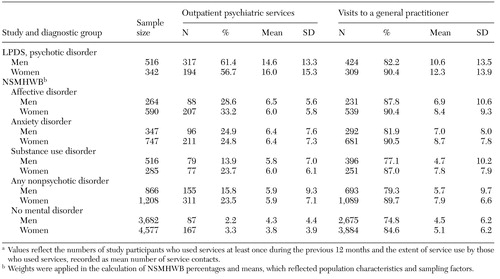

Although the service use rates shown in Table 1 generally appear to be high, they are difficult to interpret in the absence of data for other disorders or for the general community. For outpatient psychiatric services and visits to general practitioners, it was possible to derive comparable indexes from the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHWB), of which this study was a separate component. The NSMHWB was a representative household survey conducted in 1997 to establish the prevalence of nonpsychotic mental disorders in Australia (28,29). ICD-10 diagnoses in that survey were obtained by using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (30).

Data from the two studies on the use of outpatient psychiatric services and visits to general practitioners, by sex and ICD-10 diagnosis, are presented in Table 2; statistical comparisons were made between the samples but not within the NSMHWB diagnostic subgroups. Use of outpatient psychiatric services as reported in the NSMHWB was well below that obtained in the LPDS (p<.001). Although this result partially reflects the nature and sources of recruitment for the LPDS, it generally demonstrates the intensity of use of outpatient psychiatric services by persons with psychotic disorders. Among those who used services, the mean number of psychiatric outpatient contacts by persons with a psychotic disorder was more than twice that for persons with an affective disorder, an anxiety disorder, or a substance use disorder. For general practitioner services, the pattern of differences was similar for men and women; those with a psychotic disorder were just as likely to report contact with their general practitioner as those with an affective, anxiety, or substance use disorder. However, the LPDS respondents were significantly more likely to have reported contact with their general practitioner than those with no mental disorder (men: 82.2 percent compared with 74.8 percent, χ2=13.31, df=1, p<.001; women: 90 percent compared with 85 percent, χ2=8.26, df=1, p<.01). Moreover, for both men and women, the mean use of general practitioner services among persons who contacted their general practitioner was much higher (p<.001) in the LPDS sample than in each diagnosis group of the NSMHWB sample, reaching approximately 2.4 times the rate of the group with no mental disorder.

Use of other non-health-related services

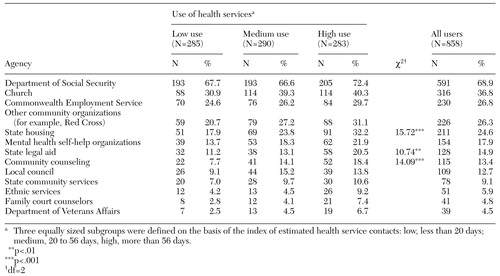

Service use by persons with psychosis clearly extends well beyond the formal health sector. Table 3 provides a breakdown of the non-health-related agencies from which study participants reported seeking help during the previous year, subdivided by overall use of health services. Use of government welfare and employment-related services, church services, and general community welfare organizations was uniformly high and was unrelated to overall use of health services. The likelihood of contact was significantly associated with health service use in three groups of non-health-related service agencies: state housing agencies, state legal aid agencies, and community counseling agencies—that is, organizations that provide specific assistance with aspects of day-to-day functioning, such as accommodation, legal assistance, and general counseling; contact rates were proportionate to health service use.

Predictors of likelihood of service use

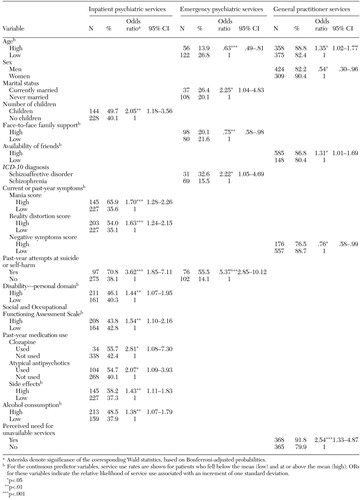

A series of hierarchical logistic regression analyses was conducted to identify predictors of the likelihood of 12-month use of health services. These analyses were restricted to the six types of services shown in Table 1 for which use was greater than 10 percent. In each logistic regression, the binary outcome variable was nonuse (designated 0) versus use (designated 1) of that service during the year. There were 41 categorical and continuous predictor variables in each analysis, with a predetermined five-step order of entry: predisposing factors (for example, age, sex, educational level, and premorbid functioning), enabling factors (marital status, number of children, family support, availability of friends, and employment and welfare status), onset of illness and course-related factors (age at onset and chronicity of illness), diagnosis-related need factors (lifetime substance abuse history and comparisons between ICD-10 diagnostic subgroups), and need factors related to symptoms, functioning, and medication (symptoms during the preceding 12 months, recent suicide or self-harm attempts, disability, current social and occupational functioning, and medication use and side effects). This hierarchy reflected the presumed (chronological) order of influence of the predictors on service use, which was formulated to be consistent with Andersen's (18) overall model of service use. The results of three of the six logistic regressions, in which there were five or more significant predictors, are summarized in Table 4. We report the results of the remaining analyses in the text.

Likelihood of using psychiatric services. All but one of the significant predictors of an inpatient psychiatric admission came from the final step in the hierarchy. Higher admission rates were reported by patients who had children, greater mania and reality distortion, recent attempts at suicide or self-harm, greater personal disability, better social functioning, use of clozapine or other atypical antipsychotics, greater impairment due to side effects of medications, and greater frequency of alcohol consumption. Among these predictors, recent attempts at suicide or self-harm had the strongest association with psychiatric admission (OR=3.62); for the other predictors, ORs ranged from 1.38 (frequency of alcohol consumption) to 2.81 (clozapine use).

Use of specific categories of antipsychotics is more likely to be a consequence of than a contributor to hospitalization. Likewise, better social functioning may not be a predictor of psychiatric admission in its own right. However, within the context of the chosen hierarchy, and after factors such as symptoms, personal disability, and sociodemographic characteristics have been controlled for, social functioning may be performing more as an index of treatment seeking capacity.

Three predictors were significantly associated with use of outpatient psychiatric services (not shown in Table 4): ICD-10 diagnosis, use of clozapine, and use of other atypical antipsychotics. Compared with patients with an ICD-10 diagnosis of schizophrenia, those in the subgroup of patients who had other psychotic disorders were less likely to have used psychiatric outpatient services (60 percent compared with 47 percent, OR=.54, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=.31 to .94, p< .05). The associations with medication status were similar to those for inpatient services (Table 4). Compared with patients who were nonusers, clozapine users and users of other atypical antipsychotics were more likely to have used psychiatric outpatient services (58.6 percent of non-clozapine users compared with 72.1 percent of clozapine users, OR= 3.19, CI= 1.25 to 8.17, p<.01; 56.6 percent of nonusers of other atypical antipsychotics compared with 70 percent of users of other atypical antipsychotics, OR=2.67, CI=1.47 to 4.85, p<.001).

Five variables were significant predictors of use of psychiatric emergency services (Table 4). Younger patients were more likely to have used these services, as were patients who were currently married, those with lower levels of family support, those with a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, and those who had made recent attempts at suicide or self-harm; this latter variable had the strongest association (OR=5.37). Only one variable was a significant predictor of use of rehabilitation services (not shown in Table 4): Patients who were not receiving welfare benefits were less likely to report use of rehabilitation services than patients who were receiving such benefits (10.6 percent compared with 20.9 percent, OR= 2.91, CI=1.24 to 6.83, p<.01).

Likelihood of using nonpsychiatric services. Only one variable significantly predicted use of nonpsychiatric emergency services. Patients who reported having fewer friends were less likely to have used such services than those who reported having more friends (8.2 percent compared with 15.1 percent, OR=1.50, CI=1.10 to 2.05, p<.001). As Table 4 shows, users of general practitioner services were less likely to report negative symptoms and were more likely to be older, to be women, to have more friends, and to have reported an unmet need—for example, as a result of the unavailability of mental health services or an inability to afford specific services.

Predictors of the extent of health service use

A parallel series of hierarchical regressions was conducted to identify predictors of the extent of 12-month use of health services by those who used services. There were seven outcome variables: the extent of use of inpatient psychiatric services (N= 370), outpatient psychiatric services (N=499), emergency psychiatric services (N=178), and rehabilitation psychiatric services (N=166); the extent of use of nonpsychiatric emergency services (N=117) and general practitioner services (N=733); and estimated health service contacts (N=858). Each analysis included 45 continuous and contrast-coded predictors, which were functionally equivalent to the predictor set used in the logistic regressions. Once again, a predetermined five-step hierarchy was used, which was consistent with Andersen's (18) model. Because the number of significant predictors was small, the results are reported in the text.

Extent of use of psychiatric services. The set of predictors was largely unrelated to the extent of use of psychiatric services. Conventionally, the squared multiple correlation (R2), expressed as a percentage, is used to describe the variance explained by a set of predictors. Across the four psychiatric services' outcome measures, the (unadjusted) explained variance was 18.1 percent for inpatient services, 11.9 percent for outpatient services, 29.0 percent for emergency services, and 28.1 percent for rehabilitation services. However, in this instance, given the variations in sample size across the outcome measures and the large number of predictors, it is also appropriate to report variance estimates based on the adjusted R2—that is, adjusted for chance associations. The corresponding (adjusted) explained variance estimates were 6.8 percent for inpatient services, 3.2 percent for outpatient services, 4.8 percent for emergency services, and 1.1 percent for rehabilitation services. The only significant predictor was use of clozapine, for which there was a positive association with the number of weeks of inpatient psychiatric admission (step 5, pr=.23, p<.001).

Extent of use of nonpsychiatric services. For the nonpsychiatric services' outcome measures, the corresponding unadjusted and adjusted explained variance estimates for emergency services were 50.9 percent and 19.9 percent, respectively; for general practitioner services the estimates were 13.1 percent and 7.4 percent. In each case, there was only one significant predictor. The number of contacts with nonpsychiatric emergency services was positively associated with attempts at suicide or self-harm (step 5, pr=.37, p<.001), and age was positively associated with the number of consultations with a general practitioner (step 1, pr=.17, p<.001).

Overall contacts with health services. Seven variables significantly predicted the number of health service contacts; the unadjusted and adjusted explained variance estimates were 16.1 percent and 11.4 percent, respectively. Patients who were receiving welfare benefits reported more contacts with health services (pr=.13, p<.01). The remaining six predictors were from the last step in the hierarchy; overall contacts with health services were positively associated with attempts at suicide or self-harm during the previous year (pr= .14, p<.001), personal disability (pr= .10, p<.05), use of clozapine (pr=.14, p<.001), use of other atypical antipsychotics (pr=.11, p<.01), use of conventional antipsychotics (pr=.10, p< .05), and greater impairment due to side effects (pr=.11, p<.01).

Discussion

It is clear that this sample of people with psychotic disorders had very high rates of service use—almost one of every two patients were admitted to an inpatient psychiatric facility during the course of a year, and a majority had extensive contacts with outpatient or community-based health services. They were two to four times as likely as people with nonpsychotic disorders to have obtained outpatient mental health services and had more than twice the number of contacts with these services. Although the patients with psychotic disorders differed little from the rest of the sample in their rates of use of general practitioner services, they averaged four or five more visits during a year than patients with nonpsychotic disorders and had more than twice the number of visits to general practitioners as those without a mental disorder.

It seems reasonable to infer that many of these additional visits were associated with mental health, disability, and related lifestyle factors. However, it is likely that only a small proportion of the visits were for explicitly acknowledged mental health problems (29,31). At an aggregate level, people with psychotic disorders were in contact with some component of the health system on an average of one day a week. Moreover, the greater their use of health services, the more likely they were to contact other helping agencies, such as state housing authorities and legal aid services.

Within the framework of Andersen's (18) behavioral model of access to health care, a number of variables were associated with the likelihood of service use. In the case of admission to inpatient psychiatric facilities, the greater risk of hospitalization associated with having children probably reflects a lower admission threshold for patients with a parenting role, owing to at least two factors. First, health professionals may be concerned about child protection and welfare issues, which may be expediently addressed by admitting the parent to a hospital. Second, the burden of family responsibilities may tax the coping capacities of persons with a psychotic disorder to a degree that overwhelms their ability to function independently.

We expected that the need factors of mania and reality distortion would increase the likelihood of hospitalization, because their exacerbation is often associated with conspicuous socially unacceptable behavior, making successful community tenure less likely. Similarly, we expected attempts at suicide and other self-harm to be associated with an increased risk of hospital admission—and related presentations to psychiatric emergency services—because of the role of hospitals in protecting patient safety and because the risk of self-harm is an important criterion for involuntary admission under mental health legislation.

Greater personal disability and its association with an increased likelihood of hospital admission probably reflects the greater need for inpatient care among persons with low competence in daily living, few or no interests, poor self-care, and generally low levels of functioning. By contrast—and paradoxically—better social and occupational functioning was also associated with a greater likelihood of admission, which may reflect these patients' greater capacity to obtain inpatient care, a lower level of tolerance of ill health, or a lower threshold in terms of seeking hospitalization.

The association of clozapine and other atypical antipsychotic drugs with the likelihood of hospital admission and the use of psychiatric outpatient services probably reflects the fact that, at the time of the study (1997– 98), these drugs may have been prescribed particularly for patients who were relatively treatment resistant or noncompliant with medication regimens. Links between impairment due to side effects and the likelihood of hospital admission and between clozapine use and the extent of psychiatric hospitalization add support to the treatment resistance or noncompliance interpretation. The association of high alcohol consumption with greater risk of hospitalization is compatible with findings of other studies on the correlates of substance use co-occurring with psychosis (8).

The association between younger age and a greater likelihood of using emergency psychiatric services is consistent with clinical experience of the early course of psychotic disorders, in contrast with later stages, when a more stable pattern of illness has generally emerged. This association is also compatible with a consistent finding from the Nordic Comparative Study on Sectorized Psychiatry, namely, that younger age is associated with a greater risk of readmission (3).

The association between increased likelihood of using emergency psychiatric services and being married and the lower likelihood of using these services among patients with strong family support appear contradictory. However, although marriage may be a vehicle for more rapid response to crises, it can be a source of stress that in itself leads to crises. High levels of family support have a protective effect in ameliorating or buffering the stressors that may otherwise precipitate crises and the need for emergency services. Schizophrenia was associated with a higher likelihood of contacting outpatient services and a relatively lower likelihood of using emergency psychiatric services. Increased use of emergency psychiatric services by patients with schizoaffective disorder probably reflects the critical nature of florid affective symptoms that may either be dramatically conspicuous or signify risk of harm to self or others, demanding an emergency response in either case.

Women were more likely than men to visit a general practitioner. However, the magnitude of the gender effect was similar for patients with psychotic disorders, nonpsychotic disorders, and no mental disorders. Older patients were also more likely to visit general practitioners and to have more frequent consultations. These patients and those with better social support and fewer negative symptoms may have psychotic disorders that are relatively stable, which would increase the likelihood of their using general practitioners as their principal form of health care. Patients who visit general practitioners also tend to recognize a service need that is unmet by other sources.

Overall, few variables predicted the extent of use of specific services (older age in relation to general practitioners, suicide or self-harm attempts in relation to nonpsychiatric emergency services, and clozapine use in relation to duration of psychiatric hospitalization). In terms of estimated total health service contacts, several statistically significant predictors were identified, although only 16 percent of the variance was explained (11 percent adjusted). These variables reflected a profile of welfare dependency, suicidal or self-harming behaviors, high personal disability, and use of antipsychotic drugs, including impairment due to side effects. Links between medication status and overall service contacts also partially reflect the fact that prescriptions are issued, renewed, and revised in conjunction with consultations.

The weak associations we observed between the predictor variables and the service use variables may have been due in part to sampling issues and, specifically, to the effects of range restriction. The LPDS sample was composed largely of persons who had had recent contact with mainstream mental health services. Use of a broader community sample, including persons with less frequent or no contact with health services, may have resulted in stronger associations. Likewise, the overall contribution of particular psychosocial and clinical variables to health service use may be higher in samples with a broader range of psychopathology.

Alternatively, studies that address individual disorders may benefit from the inclusion of prospective data or retrospective health service data, which would facilitate assessment of the predictive utility of factors such as service contact history, timing and nature of interventions received, length of stay, patterns of aftercare, and continuity of care (3,6,10,12). On the positive side, our analyses were conducted within a multivariate (hierarchical regression) framework influenced by Andersen's (18) model, as opposed to an array of univariate analyses that failed to control for relationships among the predictor variables.

Apart from potential sampling biases associated with recruiting participants who had been in relatively recent contact with services, the LPDS sample was also predominantly urban and probably underrepresentative of women with psychotic disorders. The Australian health service context in which this study was conducted also limits the extent to which international comparisons can be made. For example, Australia has geographically based health services in which public hospital and community-based services are generally free of charge, including public mental health services. General practitioners are self-employed; however, 85 percent of their consultation fees are reimbursed to patients through the government's public health insurance scheme. Moreover, most patients recruited for this study (85 percent) were receiving welfare benefits, and all had access to the subsidized public health care universally available in Australia. It is important to keep these factors in mind in any attempt to generalize these findings to other countries.

The other major limitation of the study relates to the nature of the measurements. Although the interviews were conducted by trained clinicians and incorporated standardized diagnostic assessments, many items relied solely on participants' recollections of service use without corroborative data from service records. However, we do not expect that there would have been more than minor inaccuracies due to subjective recall (25), because a number of checks to minimize such distortion were built into the interviews (20). The choice of potential comparison groups is also worthy of comment. Comparing groups with psychotic and nonpsychotic disorders, as we did, may be more appropriate in relation to use of mental health services. However, for measures such as the extent of use of general practitioner services, it may also be sensible to consider patients who do not have mental illness but who have similar levels of disability, social isolation, unemployment, dependence on welfare benefits, and access to subsidized health care.

Conclusions

People with psychotic disorders in Australia have a high rate of use of health services, particularly psychiatric inpatient and outpatient services and visits to general practitioners. Factors associated with an increased likelihood of obtaining particular psychiatric services were broadly consistent with the results of previous research—for example, younger age, social isolation, higher symptom levels, and attempts at suicide and self-harm. However, the extent of use of psychiatric services was largely unrelated to the variables investigated. A different profile emerged for general practitioner services; women, older persons, and those with more support were more likely to make contact with a general practitioner. High users of health services were also more likely to report contacts with government and community non-health-related agencies, such as housing, self-help and counseling services.

Collectively, the predictors of overall health service use were relatively poor, accounting for small proportions of the variance, which was partially explained by sampling limitations. Among patients with high rates of service use, such as those with psychosis, it may be wise in future research to pursue a broader range of issues than patient characteristics and the determinants of service use. For example, estimating the costs of psychosis, identifying psychosocial and clinical correlates, and modeling the effects of interventions that might reduce disability and promote independence are directions worth following in comprehensive data sets such as that collected for the LPDS.

We also need to clearly acknowledge the role of general practitioners in the treatment of psychosis in Australia, and, where appropriate, to provide improved education and training in patient management. It may be cost-effective to initiate and monitor psychosocial interventions that acknowledge and utilize the frequency with which people with psychosis consult their general practitioner. The ideal intervention for psychosis is presumably one that simultaneously manages symptoms, improves quality of life, reduces the burden of illness on individuals and their families, and optimizes demands on health and other community services.

Acknowledgments

The team leaders for the LPDS study were Assen Jablensky, D.M.Sc., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., Mandy Evans, M.B.B.S., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., Helen Herrman, M.D., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., and John McGrath, Ph.D., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P. A complete list of investigators can be found in references 20 and 21. The study was partly funded by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (Perth, Melbourne, and Brisbane). Data on nonpsychotic disorders from the NSMHWB are courtesy of Professor Gavin Andrews, M.D., F.R.A.N.Z.C.P., and the WHO Collaborating Centre for Evidence for Mental Health Policy in Sydney.

Professor Carr is professor of psychiatry at the University of Newcastle in Australia and director of Hunter Mental Health and the Center for Mental Health Studies. Mr. Johnston is lecturer in psychiatry at the Centre for Mental Health Studies at the University of Newcastle. Mr. Lewin is research manager at Hunter Mental Health. Dr. Rajkumar is professor at the Centre for Rural and Remote Mental Health of the University of Newcastle. Mr. Carter is director of the consultation-liaison psychiatry department of the Newcastle Mater Misericordiae Hospital and conjoint senior lecturer at the Centre for Mental Health Studies. Ms. Issakidis is research officer at the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Evidence for Mental Health Policy of the School of Psychiatry at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. Send correspondence to Professor Carr at the Centre for Mental Health Studies, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Reported use of health services during the previous 12 months among persons with an ICD-10 diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, by sexa

a Values reflect the number of study participants who used services at least once during the previous 12 months and the extent of service use by those who used services, recorded in weeks for inpatient services and number of contacts for other services.

|

Table 2. Reported use of outpatient psychiatric services and visits to general practitioners during the previous 12 months, by ICD-10 diagnosis and sex, in the Low Prevalence (psychotic) Disorders Study (LPDS) and the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHWB)a

a Values reflect the numbers of study participants who used services at least once during the previous 12 months and the extent of service use by those who used services, recorded as mean number of service contacts.

|

Table 3. Reported use of government and community (non-health-related) agencies during the previous 12 months among persons with an ICD-10 diagnosis of a psychotic disorder, by service use subgroup

|

Table 4. Significant predictors of the likelihood of 12-month service use among 858 patients with a psychotic disorder

1. Kastrup M: Who became revolving-door patients? Findings from a nation-wide cohort of first-time admitted psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 76:80-88, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Burgess PM, Joyce CMJ, Pattison PE, et al: Social indicators and the prediction of psychiatric inpatient service utilization. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 27:83-94, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Oiesvold T, Saarento O, Sytema S, et al: Predictors for readmission risk of new patients: the Nordic Comparative Study on Sectorized Psychiatry. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 101:367-373, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hirsch SR (ed): Psychiatric Beds and Resources: Factors Influencing Bed Use and Service Planning: Report of a Working Party of the Section for Social and Community Psychiatry of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. London, Gaskell, 1988Google Scholar

5. Systema S: Social indicators and admissions rates: a case register study in the Netherlands. Psychological Medicine 21:177-184, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Korkeila JA, Lehtinen V, Tuori T, et al: Frequently hospitalised psychiatric patients: a study of predictive factors. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:558-567, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Green JH: Frequent rehospitalization and noncompliance with treatment. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:963-966, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

8. Lewis T, Joyce PR: The new revolving door patients: results from a national cohort of first admissions. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 82:130-135, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Kastrup M: Prediction and profile of the long stay population: a nation-wide cohort of first-time admitted patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 76:71-79, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Jakubaschk J, Waldvogel D, Wurmle O: Differences between long-stay and short-stay inpatients and estimation of length of stay. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 28:84-90, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Zilber N, Popper M, Lerner Y: Pattern and correlates of psychiatric hospitalization in a nationwide sample: II. correlates of length of hospitalization and length of stay out of hospital. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 25:144-148, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Saarento O, Nieminen P, Hakko H, et al: Utilisation of psychiatric in-patient care among new patients in a comprehensive community-care system: a 3-year follow-up study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 95:132-139, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Fowler IL, Carr VJ, Carter NT, et al: Patterns of current and lifetime substance use in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:443-455, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Bartels SJ, Teague GB, Drake RE, et al: Substance abuse in schizophrenia: service utilization and costs. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:227-232, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Li-Tzy W, Kouziz AC, Leaf PJ: Influence of comorbid alcohol and psychiatric disorders on utilization of mental health services in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1230-1236, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Bauer MS, Shea N, McBride L, et al: Predictors of service utilization in veterans with bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders 44:159-168, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Tucker C, Barker A, Gregoire A: Living with schizophrenia: caring for a person with a severe mental illness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:305-309, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1-10, 1995Google Scholar

19. Deboer AGEM, Wijker W, Dehaes HCJM: Predictors of health care utilization in the chronically ill: a review of the literature. Health Policy 42:101-115, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Jablensky A, McGrath J, Herrman H, et al: People With Psychotic Illnesses: National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing, Report 4. Canberra, Australia, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 1999Google Scholar

21. Jablensky A, McGrath J, Herrman H, et al: Psychotic disorders in urban areas: an overview of the methods and findings of the Study on Low Prevalence Disorders, as part of the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 34:221-236, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. WHO Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO/DAS). Geneva, World Health Organization, 1988Google Scholar

23. McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I: A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness: development and reliability of the OPCRIT system. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:764-770, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, et al: SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:589-593, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Voruganti L, Heslegrave R, Awad A, et al: Quality of life measurement in schizophrenia: reconciling the quest for subjectivity with the question of reliability. Psychological Medicine 28:165-172, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

27. Gureje O, Herrman H, Harvey C, et al: Defining disability in psychosis: performance of the Diagnostic Interview for Psychosis-Disability Module (DIP-DIS) in the Australian National Survey of Psychotic Disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 35:846-851, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Andrews G, Hall W, Teeson M, et al: The Mental Health of Australians. Canberra, Australia, Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 1999Google Scholar

29. Andrews G, Henderson S, Hall W: Prevalence, comorbidity, disability, and service utilisation: overview of the Australian national mental health survey. British Journal of Psychiatry 178:145-143, 2000Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Composite International Diagnostic Interview, version 2.1. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1997Google Scholar

31. Andrews G, Issakidis C, Carter G: The shortfall in mental health service utilisation. British Journal of Psychiatry 179:417-425, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar