Psychopharmacology: Number Needed to Treat: An Underused Measure of Treatment Effect

The effectiveness of a treatment can be described in many different ways (1,2). A drug company promoting a new medication may choose to use the effectiveness measure that shows its drug in the best light. However, a clinician choosing a therapy or advising a patient needs measures that accurately reflect how one treatment compares with either a placebo or another active treatment. In this column we briefly introduce "number needed to treat" (NNT), an important but underused measure of treatment effect. NNT is believed by many statisticians, clinical epidemiologists, and advocates of evidence-based practice to be the best measure of relative treatment effectiveness (1,2,3,4,5).

Dichotomous outcome measures

In psychiatric research, especially drug trials, investigators frequently use a variety of rating scales. In reporting the results of a study, they may compare scale scores between an experimental group and a control group. Although the use of such rating scales in drug trials may be necessary for approval by the Food and Drug Administration and may generate data that can be easily analyzed, these scales have their limitations. For example, clinicians and patients cannot easily appreciate the practical implications of a small difference in scores on a particular scale.

Dichotomous outcome measures, on the other hand, are often more clinically useful (4). Examples of such measures include readmission to the hospital, achievement of full remission, a rating scale score of "improved" or "much improved," or a decrease in score of at least 50 percent. These are all measures that most clinicians and patients would consider to be clinically significant and that can be readily understood. In addition, the use of such dichotomous outcome measures allows for the calculation of a number of useful measures of clinical importance, including NNT.

In illustrating some of these measures and their calculation, we draw on the results of a hypothetical randomized controlled trial comparing an antidepressant (the experimental treatment) with a placebo (the control condition) for the treatment of major depression; the outcome measure was remission. In this hypothetical trial, 60 percent of the patients who received the antidepressant responded and 40 percent did not respond; 40 percent of the patients who received the placebo responded and 60 percent did not.

Percentage response

Percentage response is the simplest way of expressing the effectiveness of a medication and is the measure most commonly cited. However, it fails to take into account the high percentage of patients with depression and other psychiatric disorders who respond to a placebo (6,7,8). In our hypothetical study, 60 percent of the patients who received the antidepressant responded.

Absolute risk reduction

Absolute risk reduction (ARR) is a measure of the difference in percentage response between two treatments (1,2,3,4,5). When ARR is used as a measure of treatment effectiveness, the results are conventionally expressed in terms of negative outcomes—for example, nonresponse. An effective treatment is therefore one that reduces negative outcomes.

On the basis of this convention and the results of our hypothetical trial, the proportion of patients who did not respond to the placebo—termed the control event rate—was 60 percent. The proportion of patients who did not respond to the antidepressant—termed the experimental event rate—was 40 percent. ARR is the difference between the control event rate and the experimental event rate. Thus ARR=60 percent minus 40 percent=20 percent, which means that relative to the patients who received the placebo, 20 percent fewer patients who received the antidepressant failed to respond; conversely, 20 percent more of the patients who received the antidepressant did respond. These are absolute, not relative, percentage differences. Thus they can be used to estimate the percentage of patients undergoing treatment who would benefit more from the experimental treatment than the control condition. Confidence intervals for ARR may be calculated by using the formulas provided by Sackett (5) or Altman (9).

Number needed to treat

NNT represents the number of patients who would need to be treated with a specified intervention in order to obtain one additional positive outcome that would not have occurred had the patient received the comparison treatment. Alternatively, it is the number of patients who would need to be treated in order to prevent one negative outcome that would have occurred had the patient received the comparison treatment.

Although the CONSORT guidelines recommend that NNT be included in reporting the results of clinical trials (10), relatively few trials follow this recommendation (11). As a result, it is often necessary for clinicians to make the calculations themselves on the basis of data from a published article.

NNT is the reciprocal of ARR. In our hypothetical clinical trial, NNT=1/.2=5, which means that for every five patients who are treated with medication, one additional patient will respond to the medication who would not have responded to the placebo. A related measure, "number needed to harm," can be calculated as a measure of the frequency of side effects relative to the control condition.

Confidence intervals for NNT are derived from the confidence limits for ARR (5,9). They may also be calculated with the EBM calculator available on the Web site of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (www.cebm.utoronto.ca/practise/ ca/statscal/), a version of which can be downloaded to a personal digital assistant.

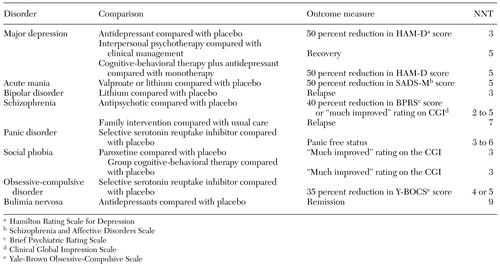

Examples of NNTs for common therapies for psychiatric disorders are given in Table 1 (6,12,13,14). Most psychiatric therapies have NNTs in the range of 3 to 6, which means that for every three to six patients treated, there is one positive outcome that would not otherwise have occurred. These NNTs compare favorably with those for other common medical therapies (5).

NNT is affected by the baseline risk of a negative outcome and may be used to derive individual estimates of treatment effectiveness for a given patient (2,5). If a patient's likelihood of improving without the experimental treatment is greater than that of patients in a study, then the patient will receive less benefit from the treatment than expected on the basis of the calculated NNT. Methods of quantifying an individual's expected benefit of treatment are given by Sackett and colleagues (5).

In summary, NNT is a useful but underused measure of the effectiveness of a treatment. Because of its popularity in systematic reviews and among proponents of evidence-based practice, NNT is a concept with which all psychiatrists should become familiar.

Dr. Pinson is a resident in general psychiatry at Martin Luther King, Jr./Charles R. Drew Medical Center in Los Angeles. Dr. Gray is professor and chairman of psychiatry and human behavior and director of the Center for Mental Health Research and Clinical Epidemiology at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science. Send correspondence to Dr. Gray at the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science, 1720 East 120th Street, AFH-1021, Los Angeles, California 90059 (e-mail, [email protected]). George M. Simpson, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Examples of "number needed to treat" (NNT) for common psychiatric disorders and treatments

1. Jaeschke R, Guyatt G, Barratt A: Therapy and understanding the results: measures of association, in Users' Guide to the Medical Literature: A Manual for Evidence-Based Clinical Care. Edited by Guyatt G, Rennie D. Chicago, AMA Press, 2002Google Scholar

2. Laupaucis A, Sackett DL, Roberts RS: An assessment of clinically useful measures of the consequences of treatment. New England Journal of Medicine 318:1728-1733, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Cook RJ, Sackett DL: The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. British Medical Journal 310:452-454, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Gray GE: Evidence-based medicine: an introduction for psychiatrists. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 8:5-13, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Sackett DL, Strauss SE, Richardson WS, et al: Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM, 2nd Edition. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 2000Google Scholar

6. Cookson J, Taylor D, Katona C: The Use of Drugs in Psychiatry: The Evidence From Psychopharmacology, 5th Edition. London, Gaskell, 2002Google Scholar

7. Preskorn SH: A dangerous idea. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 2:231-234, 1996Google Scholar

8. Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, et al: Placebo response in studies of major depression: variable, substantial, and growing. JAMA 287:1840-1847, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Altman DG: Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. British Medical Journal 317:1309-1312, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Altman DG, Schulz KF, Moher D, et al: The revised CONSORT statement for reporting randomized trials: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine 134:663-694, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Nuovo J, Melnikow J, Chang D: Reporting number needed to treat and absolute risk reduction in randomized controlled trials. JAMA 287:2813-2814, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Geddes J, Butler R: Depressive disorders. Clinical Evidence 7:867-882, 2002Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hay P, Bacaltchuk J: Bulimia nervosa. Clinical Evidence 7:834-845, 2002Medline, Google Scholar

14. McIntosh A, Lawrie S: Schizophrenia. Clinical Evidence 7:920-944, 2002Medline, Google Scholar