Volume of VA Patients With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the New York Metropolitan Area After September 11

Abstract

The authors examined data from the Veterans Integrated Service Network of New York and New Jersey to determine whether the number of veterans who were treated for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) increased significantly after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. They analyzed the number of veterans treated for PTSD at Veterans Healthcare Administration facilities in New York and New Jersey from September 1999 through June 2002. The number of veterans treated for PTSD in these facilities after September 11 exceeded projections based on secular trends, and the increase was more pronounced than for other diagnostic groups. The results highlight the need to ensure adequate availability of services in the wake of traumatic events.

The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, affected Americans profoundly. A nationwide survey conducted within days of the attacks found high levels of stress reactions in a community sample (1). In New York, stress-related symptoms were common in the immediate aftermath of the attacks.

Studies conducted one to two months after the attacks found that residents of the New York City metropolitan area had a higher rate of symptoms suggestive of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than did residents of Washington, D.C., or other major metropolitan areas (11.2 percent, 2.7 percent, and 3.6 percent, respectively) (2) and found elevated rates of acute PTSD among persons who were living close to Ground Zero at the time of the attacks (3). The impact of the September 11 attacks on clinical psychiatric populations is of particular interest. Many veterans who use services of the Veterans Healthcare Administration (VHA) are at risk as a result of preexisting mental health conditions and previous war-related trauma (4).

One published report indicated little change in the number of mental health visits to New York City VHA facilities in the first 19 workdays after the attacks (5). The number of mental health outpatient visits among adult military health care beneficiaries in Washington, D.C., did not increase significantly during the five months after the attacks (6), nor did the proportion of Manhattan residents who visited a mental health professional in the 30 days after September 11 (7). However, anecdotal reports from clinicians at local VHA facilities suggested that the number of veterans who were treated for mental illness, particularly PTSD, increased after September 11. Preliminary data analyses also suggested a change in service activity, particularly services for patients with PTSD.

In the study reported here we sought to determine whether, after September 11, 2001, there was a significant increase in the number of patients who were treated for PTSD in Veterans Integrated Service Network 3 (VISN 3), which covers the New York and New Jersey metropolitan region, and whether there was a significant increase in the number of new PTSD cases treated in VISN 3.

Methods

This retrospective study was a secondary analysis of administrative data. The institutional review board of the Bronx Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center approved the study protocol.

We obtained data from the Patient Treatment File (inpatient discharge abstracts) and the Outpatient File in the VA Austin database. We tabulated the number of unique patients who were receiving mental health treatment in VISN 3 by calendar quarter (90-day periods) and by site, dating back eight quarters before September 11, 2001, and covering three quarters subsequent to September 11, 2001 (September 17, 1999, to June 7, 2002).

We categorized each main campus in VISN 3 as a separate site and assigned community-based clinics to their parent stations, except for the Brooklyn community-based outpatient clinic (CBOC). We treated the Brooklyn CBOC as a separate site because of its proximity to the World Trade Center and because most or all of the staff and patients who were present at the clinic on September 11 had a clear view of the World Trade Center through clinic windows.

We tabulated the number of patients who had at least one mental health visit by diagnostic category, calendar quarter, and site. We analyzed data from each site separately. If a patient had a visit for a given disorder at more than one site, we counted that patient separately at each site. We counted new cases of PTSD by quarter beginning on September 11, 2000. A case was considered new for that quarter if the veteran had not been seen for PTSD in the previous 360 days—that is, since September 17, 1999. Each subsequent quarter added another 90 days to the previous "look back." Thus veterans with new cases of PTSD in the final quarter had not been seen for PTSD at that site in the previous 900 days.

To determine whether the number of veterans treated for PTSD increased significantly after September 11, we compared the observed number of veterans who received services for PTSD quarterly after September 11, 2001 (overall and by site) with the number expected on the basis of previous linear trends. We calculated 95 percent prediction intervals for the number of veterans expected to receive services at each site (based on the eight quarters before September 11) for three quarters after September 11 and compared the observed number of unique veterans who received services for PTSD with predicted numbers (8). The 95 percent prediction interval is wider—and thus more conservative—than a 95 percent confidence interval, because it allows for additional uncertainty in prediction by using an extrapolation penalty as the period of extrapolation becomes farther from September 11, 2001. We performed similar calculations for veterans receiving services for all psychiatric diagnoses and by diagnostic category.

For patients who had new episodes of PTSD we calculated predictive intervals on the basis of data from four quarters before September 11. Because additional historical data would have been needed to exclude previous treatment for PTSD (to establish it as a "new" diagnosis), a two-year lead-in was not possible.

Results

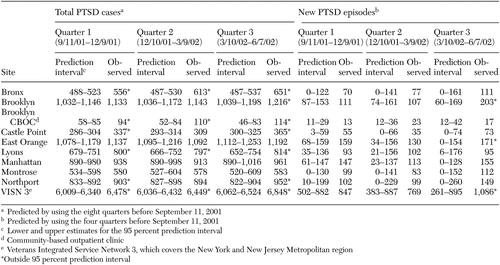

The number of unique patients who were treated for PTSD in VISN 3 increased during each of the three quarters after September 11, 2001, as can be seen from Table 1. This increase was larger than that projected on the basis of data from the preceding two years, was most pronounced in the third quarter after September 11, and was evident for six of nine sites. These results parallel an increase in the number of veterans who were treated for "all diagnoses" in VISN 3 and across diagnostic categories after September 11, but the increases are most robust for PTSD. New cases of PTSD in VISN 3 exceeded the upper limit of the 95 percent predictive interval during the third quarter after September 11.

Discussion

This study revealed an increase in the number of veterans who were treated for PTSD in VISN 3 after the September 11 attacks as well as an increase in newly diagnosed cases of PTSD over and above projections based on secular trends. The increases in the number of patients with PTSD were more robust than those for other mental disorders. Our findings contrast with those reported by Rosenheck and Fontana (9). The increase found in our study was most robust in the third quarter after the attacks. However, Rosenheck and Fontana analyzed data for six months after September 11, which may have been an insufficient period to detect a significant effect. In addition, we used a statistical model that accounted for linear change over time by using quarterly data rather than an analysis of variance based on fewer time points.

On the basis of retrospective analysis of administrative data, we cannot infer that the events of September 11 and the increase in the number of PTSD cases were causally related. Other possible reasons for the increase include clinicians' bias in diagnosing and interpreting symptoms after September 11; the impact of other stressful events, such as the anthrax scare, the airplane crash in Queens, the war in Afghanistan, and the economic downturn; substantial outreach to veterans who had previously received treatment for PTSD or depression and to veteran first responders, such as firefighters; and staffing changes at several clinics before September 11. We found no relationship between sites' geographic distance from Ground Zero and the increase in the number of veterans treated for PTSD, possibly because many people commute and socialize regionwide.

Methodologic limitations may have affected specific results of this study but not the significant findings. The fact that we counted patients who were treated at multiple sites more than once artificially inflated the total number of cases in VISN 3. However, this bias is likely to have been constant over time and should not have affected the findings. We ascertained new cases of PTSD on the basis of a variable "look back." This approach led to overcounting the number of PTSD cases that were classified as new in the early quarters compared with the later ones. This bias is a conservative one, which makes it more difficult to find a significant increase in new cases of PTSD, because the projected number of new cases is inflated—that is, calculated on the basis of overcounts from the early quarters. We used four quarters to calculate the expected number of new cases, compared with eight quarters for total cases, which results in larger predictive intervals for new cases and makes it less likely that significant increases will be detected. We could not determine whether "new" cases were truly new or were reactivated cases involving patients who had not been seen in the previous 365 to 900 days. Linearity assumptions for predictive intervals hold for "all diagnoses" and for PTSD but not for each individual diagnosis. We assessed the number of veterans who were receiving services in the VA system. However, veterans may have sought services in other sectors—for example, through such programs as Project Liberty.

Other limitations include caveats associated with secondary analyses of administrative data: coding errors, inability to prove causality, and not knowing whether PTSD symptoms were related to the terrorist attacks or were exacerbations of combat-related trauma. Numbers alone cannot capture fully the emotional impact of these traumatic events. Our results are consistent with the possibility that the September 11 attacks led more veterans to make mental health visits, but they are not definitive evidence.

Conclusions

On the basis of these results, we conclude that vigilance on the part of clinicians and administrators is warranted to ensure that adequate services are available to meet patients' needs in the wake of traumatic events.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of Veterans Integrated Service Network 3. The authors thank James Farsetta, F.A.C.H.E., and Michael Sabo, M.B.A., C.H.E.

Dr. Weissman and Dr. Marcus are affiliated with the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC) of the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the Bronx, New York, and with the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Ms. Kushner and Mr. Davis are with Veterans Integrated Service Network 3 (VISN 3), Mental Health Care Line, in the Bronx. Send correspondence to Dr. Weissman at Bronx VA Medical Center (OOMH), 130 West Kingsbridge Road, Bronx, New York 10468 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Predicted and actual number of patients treated for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during three 90-day periods after September 11, 2001, by site

1. Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al: A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. New England Journal of Medicine 345:1507–1512, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, et al: Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks. JAMA 288:581–588, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al: Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 346:982–987, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentin JD: Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 68:748–766, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck R: Reactions to the events of September 11th. New England Journal of Medicine 346:629–630, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Hoge CW, Pavlin JA, Milliken CS: Psychological sequelae of September 11 (letter). New England Journal of Medicine 347:443, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Galea S, Resnick H, Vlahov D: Psychological sequelae of September 11 (reply). New England Journal of Medicine 347:444, 2002Google Scholar

8. Hildebrand DH, Ott AL: Statistical Thinking for Managers, 4th ed. Belmont, Calif, Duxbury, 1998Google Scholar

9. Rosenheck R, Fontana F: Use of mental health services by veterans with PTSD after the terrorist attacks of September 11. American Journal of Psychiatry 160:1684–1690, 2003Link, Google Scholar