Differences Between Physical and Behavioral Health Benefits in the Health Plans of At-Risk Drinkers

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The goal of this study was to describe the physical and behavioral health benefits of a representative community-based sample of at-risk drinkers potentially in need of behavioral health services. METHODS: A screening instrument for at-risk drinking was administered by telephone to a random community sample of more than 12,000 adults. A telephone interview was conducted with the health plans of 294 at-risk drinkers who were insured and who consented to the release of their insurance records to collect information about supply-side cost-containment strategies (for example, gatekeeping and restrictions on choice of provider), and demand-side cost-containment strategies (for example, deductibles, limits, coinsurance, and copayments). Information about health plan characteristics was successfully collected for 217 (72 percent) of the insured at-risk drinkers, representing 113 different health plans and 206 different policies. RESULTS: Both provider choice restrictions and gatekeeping were more likely to be used for behavioral health care than for physical health care. Greater cost-sharing for mental health than for physical health was most often achieved by using additional limits (83 percent) and higher coinsurance (66 percent) and less often achieved by using higher copayments (38 percent) and additional deductibles (13 percent). The greater cost-sharing for behavioral health amounted to a 30 percent ($42) difference in annual out-of-pocket costs for an average user of behavioral health services compared with full parity. CONCLUSIONS: The results provide information to advocacy groups and policy makers about how much equalization would have to occur in the insurance market before full parity could be achieved between physical health and behavioral health benefits for a population of individuals potentially in need of behavioral health services.

Managed care organizations use a combination of strategies to promote health and contain costs, including supply-side and demand-side strategies. Demand-side—or cost-sharing—strategies are designed to minimize the moral hazard associated with insurance by requiring patients to pay for a proportion of health care expenditures out-of-pocket. Supply-side strategies are designed to create incentives for health care practitioners to provide services to enrollees in a more efficient and less costly manner.

Current evidence indicates that managed care has reduced the growth in health care expenditures without adversely affecting a majority of patient outcomes (1). However, it has also been argued that any adverse effects of managed care are most likely to involve particular subgroups of persons with mental illness (2,3,4). Because psychiatric disorders tend to be chronic illnesses that require multiple treatment episodes, cost-containment strategies that focus on these disorders can be expected to generate substantial savings over time (2). Likewise, the stigma associated with behavioral health treatment can reduce consumer advocacy efforts for benefit coverage. Thus there may be less resistance to reductions in behavioral health benefits than would be the case for physical health benefits.

In a 1995 Foster Higgins survey, fewer than a third of employers reported that behavioral health benefits were as generous as medical benefits (5). Despite federal and state mental health parity legislation, enrollees face higher visit limits, copayments, and coinsurance rates for mental health services than for physical health services (6,7). As a consequence, behavioral health treatment costs in large employer-sponsored health plans (8,9,10) decreased from 9 percent of expenditures in 1989 to 4 percent in 1995 (5).

Although health plan surveys conducted by Foster Higgins, the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and others have provided important information about health benefits for enrollees of health plans in general (6,7,8,9,10,11), the health benefits of a representative community-based sample of persons with behavioral health disorders have not been described. On the basis of the recommendations of Mechanic and colleagues (2) and the Institute of Medicine (3) to examine health plan access issues for high-risk populations, we examined the cost-containment strategies used by the health plans insuring a community-based sample of at-risk drinkers.

The objective of this study was to compare the health plans' behavioral health benefits with their physical health benefits. Both supply-side cost-containment strategies (for example, selective contracting, gatekeeping, and mental health carve-outs) and demand-side strategies (for example, deductibles, annual or lifetime service use limitations, coinsurance, and copayments) were examined. Because all participants in this study were current at-risk drinkers, the data provide a unique opportunity to describe the health benefits for a population of individuals who are potentially in need of behavioral health services. Benefit data were collected directly from health plan representatives rather than from enrollees, because previous research has shown that enrollees are often uninformed about their behavioral health benefits (12,13).

Methods

Enrollees and health plans

This study was part of larger study designed to examine access, service use, and outcomes over time for a group of at-risk drinkers. Details of sampling, screening, recruitment, and follow-up have been described previously (14,15). List-assisted random-digit dialing was used to create a probability-based random sample of telephone numbers from Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Tennessee. To generate a sample of approximately equal numbers of rural and urban residents, the sampling frame was stratified to oversample rural residents—that is, those not residing in a Metropolitan Statistical Area.

A brief screening instrument for at-risk drinking was administered by telephone to 12,348 adults, 960 (8 percent) of whom screened positive. The instrument defined at-risk drinking as meeting at least one lifetime DSM-IV criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence and at least one of several criteria in the previous 12 months: any abuse or dependence criteria; significant binge drinking, defined as at least 12 drinks on one occasion for men and eight drinks for women; or frequent heavy drinking, defined as at least five drinks for men and at least three drinks for women in a typical drinking day (at least once a week in the past 12 months or on at least 21 out of the previous 28 days).

A total of 733 (76 percent) of the respondents who screened positive for at-risk drinking were successfully recruited into the four-wave longitudinal study (baseline interview and six-month, 12-month, and 18-month follow-up interviews). Participants did not significantly differ from nonparticipants in demographic and clinical characteristics (16). Follow-up rates exceeded 90 percent at each wave, resulting in 573 participants (78 percent) who completed the 18-month interviews, which were administered between March 1997 and March 1998. Participants who did not complete the interviews were more likely than those who did complete the interviews to be Caucasian, male, and to live in a rural area but were not significantly different on the other dimensions examined (15).

At the completion of the 18-month interview, participants were asked to provide written consent to the collection of insurance records by the research team and to provide the names, addresses, and policy numbers of all insurers for the previous six months of the study period. The protocol and consent form were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

Written consent was provided by 442 (77 percent) of the study participants. Those who provided written consent were not significantly different in clinical or demographic characteristics than those who did not. Of those who provided consent, 142 (32 percent) reported that they were not insured or reported incorrectly that they had health insurance. Attempts were made to contact all the health plans listed by the insured study participants (N=300) in order to administer a telephone survey about the participants' benefits and coverage dates. Complete health plan survey data were collected for 217 (72 percent) of the insured participants. Those with complete health plan data were not significantly different from those who did not have complete health plan data in terms of clinical or demographic characteristics.

Research assistants contacted personnel from the customer service, claims, and provider services departments of the health plans to administer the survey. The research assistant verified that the enrollee's name corresponded with the policy number and that the coverage dates overlapped the study window. If a health plan reported that enrollees needed to get authorization from a carve-out specialty behavioral health organization to see a behavioral health specialist, the name and telephone number of the behavioral health plan was obtained. Survey items that pertained to behavioral health coverage were then administered by telephone to a representative of the specialty behavioral health organization. We successfully administered the behavioral health plan survey to 38 (70 percent) of the carve-outs. For the remaining 16 carve-outs (30 percent), we used responses about behavioral health coverage from the main health plan. The health plan information that was collected pertained to the date that the health plan survey was administered (January 1998 through June 1998), and all surveys were conducted after the Federal Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 went into effect (January 1998).

Benefit measurement

The survey asked about the type of health plan in which the at-risk drinker was enrolled: indemnity, health maintenance organization (HMO), preferred-provider organization (PPO), point-of-service (POS) plan, or other. Questions about outpatient mental health and substance abuse coverage, gatekeeping (including carve-outs), restrictions on choice of provider, deductibles, limits, coinsurance, and copayments were also included in the survey. Questions about utilization review were not asked because of measurement difficulties. The survey was designed to measure capitation at the health plan level, but the item was dropped from the analysis because 29 percent of the respondents could not answer the question.

Gatekeeping for physical health services was assessed by asking "Do enrollees have to get authorization from a primary care provider to see a medical specialist?" Gatekeeping for behavioral health services was assessed with the question "Do enrollees have to get authorization from any of the following to see a mental health or substance abuse specialist?" Respondents were asked to check all the responses that applied, including primary care physician, specialty behavioral health company, employee assistance program, health plan representative, and other/please specify.

From the perspective of an enrollee who must get authorization from a behavioral health organization, the carve-out functions as a gatekeeper to the specialty behavioral health sector. If enrollees receive care in the specialty sector, behavioral health organizations typically use additional strategies to contain costs and promote high-quality care. For enrollees who were required to get authorization from a carve-out to visit a behavioral health specialist, the additional cost-containment strategies used by behavioral health organizations—for example, provider choice restrictions, deductibles, coinsurance, copayments, and limits—were captured by separate survey items.

Provider choice restrictions for physical health services were assessed by asking "For physical health problems, are enrollees required to choose from a list of approved providers, allowed to choose any provider they want, or allowed to choose any provider but have to pay more if they don't choose from the list?" Provider choice restrictions for behavioral health services were assessed with the question "For mental health and substance abuse problems, are enrollees required to choose from a list of approved specialists, allowed to choose any specialist they want, or allowed to choose any specialist but have to pay more if they don't choose from the list?"

In responding to the survey items that were designed to gauge the four demand-side cost-sharing mechanisms—deductibles, limits, coinsurance, and copayments—respondents first indicated whether the cost-sharing mechanism was used. If an affirmative response was given, respondents were asked to indicate whether the mechanism was applied to physical health services. The survey then asked about "additional" deductibles and limits or "different" coinsurance and copayment levels for mental health services compared with physical health services and for substance abuse services compared with mental health services.

Because health plans use different combinations of mechanisms to increase cost-sharing for behavioral health, it is difficult to compare the total level of cost-sharing for physical health and behavioral health by examining each mechanism separately (10). Therefore, we created a behavioral health benefit generosity index for each health plan policy, which combines the impact of each cost-sharing mechanism into a single measure. For each health plan policy, the benefit generosity index measures the average annual out-of-pocket costs a behavioral health service user would incur for outpatient behavioral health services. The generosity index is calculated for each health plan on the basis of deductibles, coinsurance, copayments, and limits for mental health and substance abuse. Rather than specifying a standardized service use pattern based on expert opinion or treatment guidelines, we chose to base the generosity index on the actual behavioral health services used by study participants.

Annual service use data were generated for 26 users of behavioral health services by abstracting the study participants' medical and billing records to identify behavioral health diagnoses and charges. (The 17 study participants for whom psychotropic medications were prescribed but who did not receive a behavioral health diagnosis were not included in the calculation of the generosity index.) The 26 behavioral health service users differed from the nonusers in age (p<.05), sex (p<.01), employment status (p<.01), and recent alcohol disorder (p<.05). On the basis of the assumption that the 26 users of behavioral health services would have used the same amount and type of services regardless of the health plans that covered them, hypothetical annual out-of-pocket costs were calculated for each of the 26 services users as if he or she were enrolled in each of the health plans represented in the sample. This assumption would be violated if enrollees modified their service use pattern in accordance with the benefit design of their health plan in order to minimize out-of pocket costs. If the assumption were violated, the generosity index would be biased toward zero (more generous) for the selected study participant's health plan and other similar health plans.

For each health plan, the out-of-pocket costs were averaged across the 26 service users to generate the benefit generosity index. In addition, for each plan, we calculated what the out-of-pocket costs would have been if cost-sharing for behavioral health was the same as cost-sharing for physical health—that is, full parity. The difference in the generosity indexes for behavioral health and physical health represents the level of mental health parity. Because enrollees would be likely to use more behavioral health services if their behavioral health benefits were the same as their physical health benefits, this index does not represent the expected out-of-pocket costs under full parity.

Data analysis

The statistical analysis compared the use of supply-side and demand-side cost-containment strategies for behavioral health services and physical health services within plans. The GSK test (Grizzle, Starmer, and Koch) of marginal homogeneity was used to compare the distributions for gatekeeping and provider restrictions for physical health services compared with behavioral health services (17). This test determines whether the distribution of responses is the same for the physical health items as for the behavioral health items. The GSK test was an appropriate test to use because the survey responses about physical health are not independent of the survey responses about behavioral health. When each cost-sharing mechanism was examined independently, no statistical tests were used to compare the differences for physical health and behavioral health services. McNemar's paired t test was used to compare differences in benefit generosity under the existing cost-sharing levels for behavioral health and the hypothetical cost-sharing levels under full parity. Weights for study participants were calculated to reflect a combination of sampling weights, a poststratification weight, and nonresponse weights for each data-collection stage. All inferential statistics were calculated by using weights. However, all frequencies, means, and sample sizes are reported unweighted.

Results

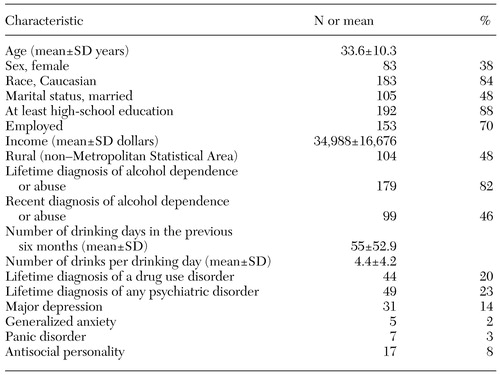

Data were collected for 217 at-risk drinkers with 113 different plans with 206 different policies. Descriptive characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 1. Overall, the sample was young, predominantly male, Caucasian, well educated, employed, and middle income. Most of the sample met criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol dependence or abuse, and about half met these criteria in the six months before baseline. The sample can be characterized as moderate to heavy drinkers, drinking 55 days in the past six months, and consuming 4.4 drinks per drinking day. Almost all (93 percent) of the enrollees' health plans covered both outpatient substance abuse and mental health services, and an additional 1 percent covered outpatient mental health services but not outpatient substance abuse services. PPOs were the most common type of health plan (42 percent), followed by HMOs (20 percent), other types of plans (21 percent), indemnity plans (11 percent), and POS plans (7 percent).

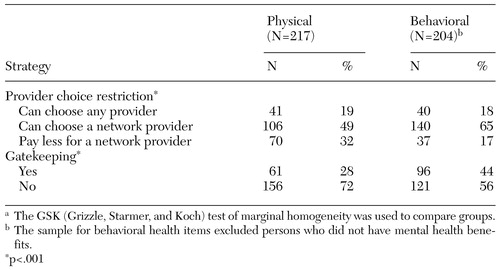

Table 2 presents data about supply-side cost-containment strategies. GSK tests indicated that the distribution of provider choice restriction strategies was different for behavioral health than for physical health. Although the ability to choose any provider was not different for physical health and behavioral health, requiring enrollees to choose from a list of providers was more prevalent for behavioral health than for physical health; conversely, paying less for a network provider was less prevalent for behavioral health than for physical health. Because of the substantial proportion (25 percent) of plans that required enrollees to get authorization from a specialty behavioral health organization before visiting a behavioral health specialist, gatekeeping for behavioral health was used significantly more often than gatekeeping for physical health.

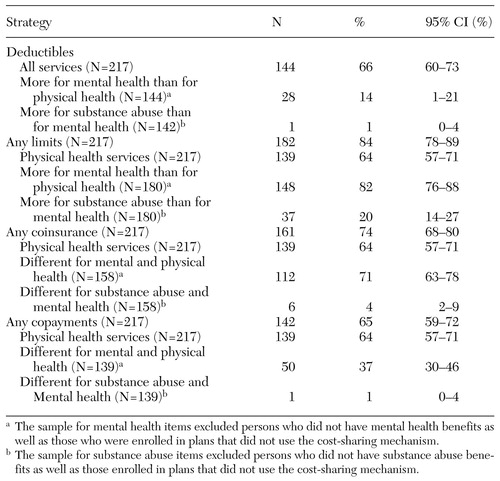

Data on demand-side cost-containment strategies are presented in Table 3. Greater cost-sharing for mental health than for physical health was most often achieved by using additional limits (82 percent) and higher coinsurance (71 percent) and less often achieved by using higher copayments (37 percent) and additional deductibles (14 percent). Greater cost-sharing for substance abuse services than for mental health services was not common among health plans. The most commonly applied cost-containment strategy targeting substance abuse was the use of additional limits beyond those targeting mental health (20 percent).

The behavioral health benefit generosity index indicated that the mean±SD annual out-of-pocket costs for users of behavioral health services was $181±$123. The generosity index ranged from zero to $494 across health plan policies. If the deductibles, limits, coinsurance, and copayments for behavioral health had been the same as those for physical health, the average annual out-of-pocket costs would have been $139±$104 (minimum of zero and maximum of $403). Thus, on the basis of the health plan benefits and behavioral health service use patterns of this representative sample of at-risk drinkers, users of behavioral health services paid 30 percent ($42) more out-of-pocket annually than they would have had to pay under full parity, assuming no change in service use patterns under parity. The paired t test indicated that this difference was statistically significant (p<.001).

Discussion and conclusions

This article presents data about the cost-containment strategies used by the health plans of insured at-risk drinkers living in urban and rural areas in the South. We detected significantly greater use of both supply-side and demand-side cost-containment strategies for behavioral health than for physical health. Provider choice restrictions were greater for behavioral health services than for physical health services. Likewise, because of the frequent requirement that enrollees get authorization from a carve-out to use behavioral health services, gatekeeping was more often used for behavioral health services than for physical health services.

At-risk drinkers also faced greater cost-sharing for behavioral health services: 82 percent faced additional limits, 71 percent faced higher coinsurance, 37 percent faced higher copayments, and 14 percent faced additional deductibles. The greater cost-sharing for behavioral health services than for physical health services amounted to a 30 percent ($42) difference in annual out-of-pocket costs for an average user of behavioral health services in the sample. Although this difference may not represent a substantial barrier to treatment for an average user of behavioral health services, this estimate is based on a sample with low to moderate annual behavioral health treatment costs (average of $538 and maximum of $2,018). The difference in out-of-pocket costs would be much greater for a high-need, high-cost user.

These results provide benchmarking data for health plans and self-insured employers concerning the distribution of physical and behavioral health benefits across the insurance market. These results also provide relevant data to mental health advocacy groups and policy makers about how much equalization will have to occur in the health insurance market before physical health and behavioral health benefits will be the same. It also provides information about the extent to which legislation mandating full parity would decrease out-of-pocket costs for at-risk drinkers who use behavioral health services, assuming no change in service use levels. Such information is needed to assess the benefits of implementing full parity. The results indicate that, for parity legislation to be effective, it must focus on cost-containment strategies other than dollar limits. The Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 mandated that dollar limits for mental health be no more than those for medical benefits for most employer-sponsored health plans. Of the employer-sponsored health plans in compliance with the Mental Health Parity Act, 87 percent reported using other cost-sharing mechanisms that are more restrictive for behavioral health services than for physical health services, thereby mitigating the impact of the legislation (18).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01-AA-12085 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to Dr. Fortney, grant P50-MH-48197 from the National Institute of Mental Health Center for Mental Healthcare Research to G. Richard Smith, M.D., and grant HFP-90-019 from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development (HSRD) Center for Mental Health Services and Outcomes Research to Richard Owen, M.D. Dr. Kirchner was supported by a VA HSRD Career Development Award (RCD-97-308). Dr. Booth was supported by an Independent Scientist Award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K02-DA-00346). The authors acknowledge the guidance and advice of the project's scientific advisory committee: James Adamson, M.D., Michael French, Ph.D., and Dennis McCarty, Ph.D.

Dr. Fortney, Dr. Booth, and Dr. Kirchner are affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center for Healthcare and Outcomes Research of the Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System in Little Rock and with the Centers for Mental Healthcare Research in the department of psychiatry at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock. Dr. Williams is with the department of biometry of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Ms. Han is with the Centers for Mental Healthcare Research in the department of psychiatry at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. Send correspondence to Dr. Fortney at Freeway Medical Tower, 5800 West Tenth Street, Suite 605, Little Rock, Arkansas 72204 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for 217 insured at-risk drinkers

|

Table 2. Comparison of supply-side cost-containment strategies for physical and behavioral health carea

a The GSK (Grizzle, Starmer, and Koch) test of marginal homogeneity was used to compare groups.

|

Table 3. Demand-side cost-containment strategies for physical health, mental health, and substance abuse treatment

1. Iglehart JK: Managed care and mental health. New England Journal of Medicine 334:131-135, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Mechanic D, Schlesinger M, McAlpine DD: Management of mental health and substance abuse services: state of the art and early results. Milbank Quarterly 73(1):19-54, 1995Google Scholar

3. Edmunds M, Frank R, Hogan M, et al: Managing Managed Care: Quality Improvement in Behavioral Health. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1997Google Scholar

4. Schlesinger M, Wynia M, Cummins D: Some distinctive features of the impact of managed care on psychiatry. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 8:216-230, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Buck JA, Umland B: Covering mental health and substance abuse services. Health Affairs 16(4):120-126, 1997Google Scholar

6. Buck JA, Teich JL, Umland B, et al: Behavioral health benefits in employer-sponsored health plans, 1997. Health Affairs 18(2):67-78, 1999Google Scholar

7. Jensen GA, Rost KM, Burton RPD, et al: Mental health insurance in the 1990s: are employers offering less to more? Health Affairs 17(3):201-208, 1998Google Scholar

8. Salkever DS, Shinogle J, Goldman H: Mental health benefit limits and cost sharing under managed care: a national survey of employers. Psychiatric Services 50:1631-1633, 1999Link, Google Scholar

9. Druss B, Levinson C, Marcus S: Employer-based mental health benefits: implications for mental health parity. Psychiatric Services 51:455, 2000Link, Google Scholar

10. Hodgkin D, Horgan CM, Garnick DW, et al: Cost sharing for substance abuse and mental health in managed care plans. Medical Care Research and Review, in pressGoogle Scholar

11. Substance abuse provisions in employee benefit plans. Bulletin 2412. Washington, DC, US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1992Google Scholar

12. Cunningham PJ, Denk C, Sinclair M: Do consumers know how their health plan works? Health Affairs 20(2):159-166, 2001Google Scholar

13. Mickus M, Colenda CC, Hogan AJ: Knowledge of mental health benefits and preferences for type of mental health providers among the general public. Psychiatric Services 51:199-202, 2000Link, Google Scholar

14. Booth BM, Ross RL, Rost K: Rural and urban problem drinkers in six Southern states. Substance Use and Misuse 34:471-493, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Booth BM, Fortney SM, Fortney JC, et al: Short-term course of drinking in an untreated sample of at-risk drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 62:580-588, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Booth BM, Kirchner J, Fortney J, et al: Rural at-risk drinkers: correlates and one-year use of alcohol services. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 61:267-277, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Grizzle JE, Starmer CF, Koch GG: Analysis of categorical data by linear models. Biometrics 25:489-504, 1969Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Committee on Health Education Labor and Pensions, and US Senate: Mental Health Parity Act: Despite New Federal Standards, Mental Health Benefits Remain Limited. Washington, DC, US General Accounting Office, Health, Education, and Human Services Division, 2000Google Scholar