Combination Antipsychotic Therapy in Clinical Practice

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Surveys have shown that antipsychotic drug combinations are frequently prescribed, yet few clinical studies have examined this practice. Experts have generally recommended antipsychotic combinations, especially those combining an atypical and a conventional antipsychotic, as a measure of last resort. A survey of prescribers was conducted to examine why combination antipsychotic therapy is being used in outpatient clinical practice. METHODS: Antipsychotic prescribing practices in the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health System were reviewed for a six-month period during 1998-1999. Data on the use of atypical and conventional antipsychotics in combination were collected. RESULTS: A total of 1,794 patients received prescriptions for at least one antipsychotic medication during the study period, of which 715 (40 percent) received an atypical agent. Ninety-three patients (13 percent) who were treated with an atypical antipsychotic received a prescription for combination antipsychotic therapy for at least 30 days. In cases in which both a conventional and an atypical agent were prescribed, the primary reason given for adding a conventional antipsychotic medication was to treat persistent positive symptoms. The primary reason an atypical agent was added to a conventional agent was to switch medications to the atypical agent; however, a significant number of patients became "stuck" on the combination. CONCLUSIONS: The results of this study support previous reports of the frequent use of combination antipsychotic therapy in clinical practice. Prospective controlled trials are needed to substantiate perceptions that combination antipsychotic therapy is clinically beneficial and to provide guidelines on when and for whom antipsychotic polypharmacy should be considered.

The goal of this study was to evaluate providers' rationale for the frequent yet poorly studied practice of combining antipsychotic medications. The results of three different surveys suggest that up to 25 percent of outpatients with schizophrenia may be receiving antipsychotic polypharmacy, usually consisting of both an atypical and a conventional agent (1). In the extended care units at a Texas State Hospital, more than 50 percent of the patients who were treated with atypical antipsychotics received a second antipsychotic agent and in some cases a third agent. The most frequently coprescribed medication was a potent D2-receptor blocker (2). In a survey of four mental health centers, 4 percent of patients who were treated with clozapine, 12 percent of patients treated with olanzapine, and 20 percent of patients treated with risperidone also had a conventional antipsychotic prescribed (3).

Similar patterns of polypharmacy have been noted internationally. In a study in Australia, 13 percent of all outpatients received more than one antipsychotic medication (4). In a French study, an average of 1.4 antipsychotic medications were prescribed for persons with schizophrenia and other psychoses (5). In a study in Austria, 47 percent of patients received prescriptions for two antipsychotic medications, and 8 percent received prescriptions for three medications (6). A survey from Japan found the highest rates of polypharmacy: a combination of a high-potency and a low-potency antipsychotic medication was prescribed for more than 90 percent of inpatients with schizophrenia (7).

Although polypharmacy is common, studies of this practice are lacking. Stahl (8) called the lack of controlled trials of the effectiveness of antipsychotic combinations a "dirty little secret." Only a few studies have examined the practice of combining antipsychotics, and they have been limited by small samples. A group of studies have examined the effect of adding a second antipsychotic to clozapine. These studies have indicated that risperidone, olanzapine, pimozide, and loxapine may be helpful in reducing psychotic symptoms when used as adjuncts to clozapine (9,10,11,12,13,14). In the only controlled double-blind study of combination antipsychotic therapy, Shilo and colleagues (15) studied the augmentation of clozapine with amisulpiride, a conventional antipsychotic that is not available in the United States. The study sample consisted of 28 patients with treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Sixteen patients were randomly assigned to receive 600 mg of amisulpiride plus clozapine a day, and 12 received placebo plus clozapine. Significant reductions in symptoms were noted at the end of ten weeks among patients who received the amisulpiride-clozapine combination, as measured by scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and on separate measures of positive and negative symptoms.

Other investigators have reported on combinations of a conventional agent and atypical antipsychotics other than clozapine. Goss (16) reported that the addition of thioridazine to risperidone reduced anxiety and agitation among a few patients. Bacher and Kaup (17) examined the effect of adding low-dosage risperidone (1 mg to 2 mg) to conventional neuroleptics among 18 patients with chronic and refractory schizophrenia. They noted slight to moderate improvements in anxiety and reductions in hallucinations for ten of 18 patients. In a more recent study, Waring and colleagues (18) treated 31 patients who had treatment-refractory schizoaffective disorder with low-dosage conventional neuroleptics such as haloperidol, trifluoperazine, and fluphenazine combined with the atypical agents risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine. These researchers observed clinical improvement without serious side effects among two-thirds of these patients. However, the study had a number of methodologic limitations, including uncertainty about diagnosis and treatment-refractory status as well as the questionable adequacy of treatment with the atypical agents as monotherapy (3).

Atypical antipsychotics have been noted to have superior beneficial effects in terms of extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, prolactin secretion, negative symptoms, and cognition. Antipsychotic polypharmacy may interfere with these beneficial effects (3). For this reason, published expert guidelines have recommended polypharmacy only as a last resort. In the Expert Consensus Guideline Series (19), combination antipsychotic therapy is presented as an option only after sequential trials of conventional antipsychotics and one or more newer atypical antipsychotics, including clozapine, have failed to bring relief of prominent positive symptoms. In the procedural manual for the schizophrenia module of the Texas Algorithm, antipsychotic polypharmacy is considered only after trials with four atypical antipsychotics, including clozapine, have failed (20).

However, because new-generation antipsychotic medications appear to have a different efficacy profile both from conventional agents and from each other, there may be a rationale for the use of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Because conventional agents may have a more rapid onset of action, it has been suggested that they be used as a lead-in with an atypical agent, to control psychotic symptoms until the atypical agent becomes effective (8). Another possible use might be to "top up" by adding a conventional to an atypical agent when symptoms worsen in order to prevent a full exacerbation of psychotic symptoms (2,8). Third, combination antipsychotic therapy may result from cross-tapering designed to change an antipsychotic regimen; if the patient starts to respond favorably, the clinician or the patient may be unwilling to change the medication regimen, and the patient becomes "stuck" on the combination therapy (8).

In the study reported here, pharmacy records were reviewed to examine the frequency of antipsychotic polypharmacy, with a particular focus on both the least-recommended and the most-frequent combination in which an atypical and a conventional antipsychotic are used concomitantly. We also present the results of a survey of practitioners who prescribed a combination of a conventional and an atypical antipsychotic, to investigate their rationale for using this form of polypharmacy.

Methods

Outpatient pharmacy records for the Seattle and American Lake Divisions of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Puget Sound Health Care System were reviewed to identify prescriptions filled for any antipsychotic medication within a six-month period (September 1998 to March 1999). The number of patients taking a conventional or an atypical antipsychotic or a combination of antipsychotic medications was obtained. If a patient had received prescriptions for more than one antipsychotic agent during the six-month period, medical records were reviewed to ascertain whether the patient was ever taking both medications at the same time. If the combination had been prescribed for the patient for at least 30 days, the patient was included in the study.

A survey of clinicians was then developed to ascertain why both a conventional and an atypical agent had been prescribed and what specific symptoms were targeted. The clinicians were asked to rate whether the combination of medications had improved specific symptoms. The specific symptom dimensions were chosen from items on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (21). These symptoms included hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, elevated mood, depression, flat affect, preoccupation, anhedonia, poor hygiene, conceptual disorganization, impulsivity, hostility, anxiety, alogia, avolition, and poor attention. Information was also collected on the age, sex, and diagnosis of the patient. Surveys were completed either by directly communicating with the provider or by reviewing charts. A majority of the surveys were completed with the input of providers.

This survey was conducted as part of a continuous quality assurance project, and no patients were interviewed specifically for the purpose of obtaining information for the study. The American Lake Division was chosen as the study site because it serves more patients with severe chronic schizophrenia, a population more likely to have combination antipsychotic therapy prescribed, than the Seattle Division. Approval to conduct the review of patient medical records was obtained from the human subjects committee of the local internal review board.

Results

During the six-month study period, 1,794 outpatients had a prescription filled for at least one antipsychotic medication, of whom 715 received an atypical antipsychotic. At the first count, 123 patients who had a prescription filled for an atypical agent were found to have received a second antipsychotic during the six-month time frame. After a chart review, 30 patients were excluded from the study because we could not confirm that they had been receiving the combination for at least 30 days. Of the 93 remaining patients, 74 received a combination of an atypical and a conventional agent, and 19 received a combination of two atypical agents. Thus, of all patients who had a prescription filled for an atypical antipsychotic, 13 percent received a secondary antipsychotic for at least 30 days.

Of the 74 patients for whom antipsychotic polypharmacy was prescribed, 42 were being treated at the American Lake Division. Of 22 providers in the mental health service of the American Lake Division, 12 had prescribed a combination of an atypical and a conventional antipsychotic. All these cases were surveyed. However, in one case the data were insufficient for completion of the survey. Of the 41 patients for whom surveys were collected, 39 were men and two were women. Thirty patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Of the remaining patients, nine had schizoaffective disorder, one had delusional disorder, and one had Alzheimer's-associated dementia with delusions. The two patients who did not have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were excluded from the analysis, because this study was concerned mainly with the prescribing practices for these disorders.

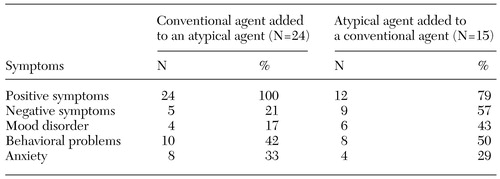

Of the remaining 39 patients, 24 (62 percent) had a conventional agent added to an atypical antipsychotic, and 15 (38 percent) had an atypical agent added to a conventional agent. For cases in which the combination therapy involved the addition of a conventional agent to an atypical agent, all the prescribers indicated that this decision was made for therapeutic reasons, primarily to help control persistent positive symptoms. Of the 15 patients for whom an atypical agent was added to a conventional agent, one was in the process of switching to the atypical agent and 12 had been "caught" in the switch—that is, although the intention had been for the patient to switch completely to the atypical agent, the patient started doing better on the combination and either the prescriber or the patient was unwilling to discontinue the conventional agent. The remaining two patients had been given an atypical agent to augment the action of the conventional antipsychotic. The main reason given for prescribing a secondary antipsychotic, whether conventional or atypical, was to improve persistent positive symptoms. Table 1 lists the symptoms that clinicians described as being improved by the addition of a secondary antipsychotic agent.

The use of clozapine was examined for all 42 patients at the American Lake Division who had received a combination of a conventional and an atypical agent. Four patients were receiving combinations with clozapine at the time of the survey, but none of the remaining patients had ever received clozapine. (No patients at the Seattle division were receiving clozapine in combination.) The same 42 patients were reviewed one year later to assess their use of clozapine. As of March 2000, three of these patients who had not previously received a prescription for clozapine had been switched from the conventional-atypical combination to clozapine.

Discussion

We found that within a six-month period, 13 percent of all patients in the VA Puget Sound Health Care system for whom an atypical antipsychotic was prescribed also received a prescription for a secondary antipsychotic. This rate is lower than those reported in other studies. The differences may be related to the populations sampled. Our study primarily included stable outpatients, whereas Ereshefsky (2) reported on a sample of inpatients with persistent mental illness. Thus patients with a more treatment-refractory or severe course of illness and those in acute treatment settings are more likely to receive antipsychotic polypharmacy. Also, patients with schizophrenia may be more likely to receive antipsychotic polypharmacy than patients with other disorders.

In our survey of prescribers at the American Lake Division, we found that 73 percent of patients for whom the combination of conventional and atypical antipsychotics had been prescribed had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Had we limited our focus to patients with schizophrenia, as was done in other surveys (5,7), the proportion of patients for whom antipsychotic polypharmacy was prescribed may have been higher. Another factor that may have resulted in an underestimation of antipsychotic polypharmacy rates is the fact that depot medication prescriptions are not recorded in the pharmacy database as frequently as oral medications, and so we may not have captured all cases of depot medication prescriptions.

The data we obtained suggest that when a patient receives a combination of atypical and conventional antipsychotics for more than 30 days, he or she is likely to continue on that combination. In only one of the 39 cases was the clinician still intending to discontinue one of the medications.

The larger proportion of patients who continued to receive a combination of antipsychotics in this study had initially received a prescription for an atypical antipsychotic. In general, clinicians added a conventional antipsychotic to target positive symptoms of schizophrenia and reportedly found this intervention to be effective for 100 percent of the patients. However, an interesting phenomenon was observed when an atypical antipsychotic agent was added to a conventional agent. Clinicians intended to have patients switch to the atypical agent and in the process found the combination so advantageous that they were reluctant to discontinue the conventional agent. Clinicians estimated that this combination improved patients' symptoms, sometimes even before the patient had been tried on the atypical agent alone. Patients who receive these combinations are exposed, perhaps unnecessarily, to a greater risk of side effects associated with conventional neuroleptics, such as tardive dyskinesia.

Our findings on the use of clozapine are also interesting. Only 4 percent of patients for whom combination therapy was prescribed had received a prescription for clozapine. Despite clinical guidelines that recommend that clozapine be tried before a combination antipsychotic regimen is prescribed (19,20), some clinicians have chosen to try polypharmacy first. Clinicians may choose this option for several reasons. First, clozapine requires continuous monitoring, which necessitates considerable coordination of resources in order to bring a patient into the clinic on a regular basis. Second, some patients may refuse to undergo phlebotomy on such a frequent basis. Considering these obstacles, clinicians may find it considerably easier to add a second antipsychotic agent rather than to prescribe clozapine.

These examples highlight how clinical practice may diverge from experts' recommendations. This problem has been well demonstrated in the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) project (22). Another important issue is the targeting of symptoms. Positive symptoms remain the focus of treatment in schizophrenia in clinical practice. However, current knowledge demonstrates that negative symptoms—and, more important, cognitive dysfunction—lead to more disability and poorer functional outcome in schizophrenia (23).

This study had several limitations that restrict interpretation of the data. One major limitation was the retrospective study design. There were no objective ratings of clinical condition or structured interviews, so our results cannot be used to evaluate the effectiveness of the use of antipsychotic polypharmacy. Optimally, this examination should be conducted in a prospective double-blind fashion. Another limitation was the lack of data on the mean duration of combination antipsychotic therapy. It would be interesting to know whether patients who were "stuck" during cross-titration continued to receive the combination on a long-term basis. This question is especially relevant in light of the risk of exposure to tardive dyskinesia. The methods used in this study also probably resulted in an underestimation of antipsychotic polypharmacy rates, because not all the patients for whom depot medication was prescribed were captured and thus not all were included in the analysis.

Another question unanswered by this survey relates to dosage and the threshold at which clinicians should consider augmentation rather than an increased dosage of the initial antipsychotic. Finally, this study was conducted among stable outpatients who were predominately male. Thus our findings cannot be generalized to women or to other treatment settings.

Conclusions

We found that combination antipsychotic therapy was prevalent in a large metropolitan VA medical center. As a result of the frequency with which patients are exposed to the risk of newer antipsychotic agents combined with conventional neuroleptics, and because providers believe that this combination is advantageous to the patient, future studies are urgently needed to examine the effectiveness and risks of combination antipsychotic therapy. Assessment of benefits should include not only traditional positive and negative symptoms but also cognitive function and community or social outcome. Such data are required in order to guide rational antipsychotic polypharmacy for patients with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maya Chandran, M.D., Dance Smith, Pharm.D., and Murray Raskind, M.D.

The authors are affiliated with the Department of Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System in Tacoma, Washington. Dr. Tapp, Dr. Wood, and Dr. Kilzieh are also with the department of psychiatry of the University of Washington in Seattle. Send correspondence to Dr. Tapp at Mental Health Services (A-116-R), VA Puget Sound Health Care System, American Lake Division, Tacoma, Washington 98493 (e-mail, [email protected]). A version of this paper was presented at the winter workshop on schizophrenia, held February 5-11, 2000, in Davos, Switzerland, and at the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology December 10-14, 2000, in Las Croabas, Puerto Rico.

|

Table 1. Improvements in symptoms among patients with schizophrenia who received combination antipsychotic therapy, as reported by physicians

1. Stahl SM: Selecting an atypical antipsychotic by combining clinical experience with guidelines from clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 10):31-39, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

2. Ereshefsky L: Pharmacologic and pharmacokinetic considerations in choosing an antipsychotic. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 10):20-30, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

3. Meltzer HY, Kostaoglu AE: Combing antipsychotics: is there evidence for efficacy? Psychiatric Times 17(9):25-34, 2000Google Scholar

4. Keks NA, Altson K, Hope J, et al: Use of antipsychosis and adjunctive medications by an inner urban community psychiatric service. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 33:896-901, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Fourrier A, Gasquet I, Allicar MP, et al: Patterns of neuroleptic drug prescription: a national cross-sectional survey of a random sample of French psychiatrists. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 49:80-86, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Rittmannsberger H, Meise U, Schauflinger K, et al: Polypharmacy in psychiatric treatment: patterns of psychotropic drug use in Austrian psychiatric clinics. European Psychiatry 14:33-40, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Ito C, Kubota Y, Sato M: A prospective survey on drug choice for prescriptions for admitted patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 53:S35-S40, 1999Google Scholar

8. Stahl SM: Antipsychotic polypharmacy: I. therapeutic option or dirty little secret? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:425-426, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Friedman J, Ault K, Powchik P: Pimozide augmentation for the treatment of schizophrenia patients who are partial responders to clozapine. Society of Biological Psychiatry 42:522-523, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Gupta S, Sonnenburg SJ, Frank B: Olanzapine augmentation of clozapine. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 10:113-115, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Henderson DC, Goff DC: Risperidone as an adjunct to clozapine therapy in chronic schizophrenics. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:395-397, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

12. Morerra AL, Barreiro P, Cano-Munoz JL: Risperidone and clozapine combination for the treatment of refractory schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 99:305-306, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Mowerman S, Siris SG: Adjunctive loxapine in a clozapine-resistant cohort of schizophrenic patients. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 8:193-197, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Raskin S, Katz G, Zislin Z, et al: Clozapine and risperidone: combination/augmentation treatment of refractory schizophrenia: a preliminary observation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 101:334-336, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

15. Shiloh R, Zemishlany Z, Aizenberg D, et al: Sulpiride augmentation in people with schizophrenia partially responsive to clozapine: a double-bind, placebo-controlled study. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:569-573, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Goss JB: Concomitant use of thioridazine with risperidone. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 15:443, 1995Google Scholar

17. Bacher NM, Kaup BA: Combining risperidone with standard neuroleptics for refractory schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:137, 1996Link, Google Scholar

18. Waring EW, Devin PG, Dewan V: Treatment of schizophrenia with antipsychotics in combination. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 44:189-190, 1999Google Scholar

19. Expert Consensus Guideline Series: treatment of schizophrenia 1999. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 11):3-80, 1990Google Scholar

20. Miller AL, Chiles JA, Chiles J, et al: Procedural Manual: Schizophrenia Module Physician Manual. Unpublished manuscript, Texas Medication Algorithm Project, 1998Google Scholar

21. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261-276, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Lehman FA, Steinwachs DM, and the co-investigators of the PORT project: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11-20, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Green MF, Kern RS, Braff DL, et al: Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the "right stuff"? Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:119-136, 2000Google Scholar