Factors Associated With Missed First Appointments at a Psychiatric Clinic

Abstract

This study identified characteristics ofpatients who missed their intake appointments at a university psychiatric outpatient clinic for persons with serious mental illness after referral from a state agency. Of the 313 patients whose charts were reviewed, 113 (36 percent) missed their appointment. Demographic characteristics, DSM-IV diagnoses, clinician rating scales, and psychopharmacological therapy were compared between attenders and nonattenders. Five predictors of nonattendance were significant: being younger, being Hispanic, having a poor family support system, not taking psychotropic medications, and having health insurance. Persons at greater risk of missing their intake appointment may be prospectively identified and targeted for measures to improve compliance.

In outpatient psychiatric clinics, missed appointments can compromise quality of care and reduce the efficiency of resource allocation. Initial appointments are more frequently missed, are less often rescheduled, and require more staff time than appointments for ongoing treatment (1). Studies to identify patients at risk of missing initial appointments in a variety of outpatient psychiatric treatment settings have yielded inconsistent results (1). Younger age (2,3), low socioeconomic status (4), and longer waiting periods from contact to appointment (3,4) are the factors most consistently associated with nonattendance. Knowledge of the characteristics of those who attend and those who do not in a particular setting allows the prospective identification of patients at risk and can lead to program modifications to reduce the risk and rate of nonattendence.

Methods

The sample population included 313 patients with scheduled appointments at a Southwestern medical-school-affiliated psychiatric outpatient clinic from April through August 2000. Study subjects were referred by the Texas Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation, a public-sector state agency that provides mental health services to persons with serious mental illness who meet specific diagnostic and financial criteria. Patients were given a specific date and time for an appointment at this clinic, which was within their catchment area and thus accessible to them. Data were obtained from medical records, including clinicians' ratings on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (5), agency assessment using the Multnomah Community Ability Scale (MCAS) (6), and a structured interview assessment of sociodemographic information.

The explanatory variables in this study can be categorized as predisposing, enabling, and need factors in accordance with the behavioral model of health services utilization of Andersen and Newman (7). Predisposing variables include age, sex, ethnicity, living situation, education, and legal trouble. Enabling variables include marital status, employment status, sources of financial support, annual income, and insurance status. Need variables included alcohol use, drug use, diagnoses, medications, inpatient history, BPRS score, and MCAS score. Tolerance statistics and Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine correlations between predictor variables.

Logistic regression was used to identify factors associated with appointment attendance. Bivariate models of each explanatory variable assessed how useful the variable was at predicting whether patients would attend their appointments. A multivariate logistic model was used to determine which variables were independently associated with attendance after the other measured characteristics were controlled for.

Results

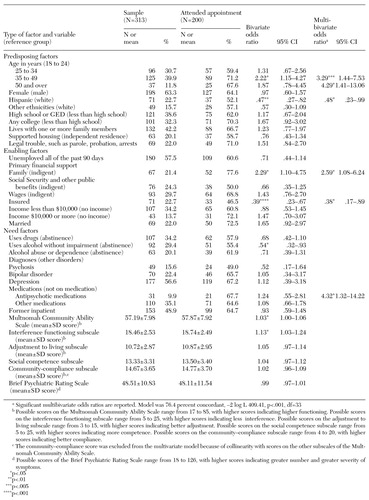

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics for the sample population. Of the 313 patients, 113 (36 percent) failed to attend their appointment at the psychiatric outpatient clinic. The majority of the study population were female, non-Hispanic white, unmarried, living alone in an independent residence, uninsured, unemployed during the past 90 days, and without income.

Bivariate logistic analysis

Seven characteristics were significantly different (p<.05) between those who attended their appointment and those who did not (Table 1). An age of 35 to 49 years (versus under 25), receipt of family financial support, and higher MCAS scores were positively associated with attendance at the scheduled appointment (odds ratios greater than 1). Hispanic ethnicity, having health insurance (including Medicaid and Medicare), and use of alcohol without impairment (versus abstinence) were negatively associated with attendance (odds ratios less than 1).

Multivariate analysis

The odds ratios of significant explanatory variables in the multivariate model (Table 1) indicate the relative likelihood that an individual with that characteristic would attend the appointment compared with an individual without the characteristic, when other variables are controlled for. Six variables were significant (p<.05): age of 35 to 49 years or 50 to 64 years, receipt of family financial support, and use of antipsychotic medication were positively associated with attendance. Hispanic ethnicity and having insurance were negatively associated with attendance—that is, Hispanics and patients with insurance were more likely to miss their appointment.

Use of antipsychotic medication and the highest age group were significantly associated with attendance in the multivariate but not in the bivariate model. This finding can be explained by correlations with other model variables. Use of antipsychotics was correlated with patients' diagnoses, and higher age was correlated with receipt of public financial support and insurance. However, examination of the tolerance statistics and correlation coefficients revealed that multicollinearity was not a problem.

Discussion

Although the "no-show" rate of 36 percent for this public-sector outpatient clinic was well within the range of the 26 to 50 percent previously reported for initial appointments (4), this rate is nevertheless cause for concern. Patients who do not attend their appointments are at risk of being rehospitalized or of endangering themselves and others (8).

At least one study found that most patients who miss psychiatric appointments reschedule within two weeks of the original appointment (1). The problems of patients who do not spontaneously reschedule may resolve without professional care (1,9). However, this is unlikely to be the case among patients with severe mental illness, who constituted the patient population treated in the study clinic.

Our finding that patients aged 35 and older are more likely to attend their outpatient appointment than those under 25 is consistent with previous research (2,3,4). The relationship between higher age and attendance may be related to previous psychiatric treatment, which is associated with attendance (2).

The relationship between ethnicity and not attending the initial appointment is consistent with previous studies that reported less use of mental health services by Hispanics. Cultural barriers are often cited as the reason for less use by Hispanics when financial access is controlled for (10).

The finding that the receipt of family support is related to appointment attendance suggests that such support may help to overcome financial barriers or that family members who provide financial support may also encourage the patient to obtain psychiatric care. Family support has been proposed as one mechanism that enables patients to seek care (2).

The relationship between insurance and a lower likelihood of attending the initial appointment is interesting and suggests several policy issues connected with the relationship between access to care and funding. The findings of this study suggest that individuals who have health insurance, including Medicaid, have alternative treatment options and may use them if they offer advantages to treatment in a public-sector agency. While quality of care may not be adversely affected under these circumstances, they may contribute to inefficient use of staff and agency resources.

A major limitation of this study is that we had incomplete information about previous involvement with the psychiatric care system and about whether patients were referred from inpatient or community settings—factors that are known to affect appointment attendance (2). Unfortunately, neither the date of hospital discharge nor the initial date of referral were consistently documented in the data available for review. This inconsistency also precluded the calculation of another important variable, the time between initial referral and the date of the scheduled appointment.

The important role we observed for antipsychotic medications is consistent with findings of studies that have identified a relationship between previous psychiatric treatment and appointment attendance (2). Patients who take medications may be more motivated to attend their scheduled appointments, particularly if the benefit of medications is evident to them or their caregivers.

Conclusions

This study identified patient characteristics associated with attendance at an initial appointment at a university-based outpatient psychiatry clinic after referral by a state agency. This information can be used to identify patients who are at risk of not attending their initial appointment and to design interventions to reduce the risk factors for nonattendance.

At the time of this study, Ms. Kruse was a research assistant in the department of health services research and management of the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC). Dr. Rohland is associate professor and regional chair of the department of psychiatry of TTUHSC-Amarillo. Dr. Wu was a resident in psychiatry at the TTUHSC School of Medicine in Lubbock. Send correspondence to Dr. Rohland, Department of Psychiatry, TTUHSC-Amarillo, 1400 Wallace Boulevard, Amarillo, Texas 79106 (e-mail, [email protected]). An abstract of this material was presented as a poster at the annual meeting of American Psychiatric Association held May 5-10, 2001, in New Orleans.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of patients referred by a public-sector agency to an outpatient clinic for persons with serious mental illness, by whether or not they attended their first appointment

1. Sparr LF, Moffitt MC, Ward MF: Missed psychiatric appointments: who returns and who stays away. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:801-805, 1993Link, Google Scholar

2. Carpenter PJ, Morrow GR, Del Gaudio AC, et al: Who keeps the first outpatient appointment? American Journal of Psychiatry 138:102-105, 1981Google Scholar

3. Nicholson IR: Factors involved in failure to keep initial appointments with mental health professionals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:276-278, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Chen A: Noncompliance in community psychiatry: a review of clinical interventions. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:282-287, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Ventura J, Leukoff D, Neuchterlein KH, et al: Manual for the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 3:221-224, 1993Google Scholar

6. Barker S, Barron N, McFarland BH, et al: A community ability scale for chronically mentally ill consumers: I. reliability and validity. Community Mental Health Journal 30:363-383, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Andersen R, Newman J: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly Health and Society 51:95-124, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Nelson EA, Maruish ME, Axler JL: Effects of discharge planning and compliance with outpatient appointments on readmission rates. Psychiatric Services 51:885-889, 2000Link, Google Scholar

9. Peeters FPML, Bayer H: "No-show" for initial screening at a community mental health center: rate, reasons, and further help-seeking. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:323-327, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, et al: Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: findings from a national sample. Medical Care 40:52-59, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar