Veterans Who May Need a Payee to Prevent Misuse of Funds for Drugs

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study sought to determine the possible need for a payee among Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) inpatients with substance use disorders who receive public support payments. METHODS: A total of 290 veterans hospitalized in VA psychiatric units completed a survey designed to identify patients who may be in need of a payee because of excessive expenditures for substances of abuse. Level 1 screening identified patients with a general likelihood of needing a payee because they received public support payments, did not have a payee, and had a substance abuse diagnosis. Level 2 screening identified level 1 patients for whom there was further evidence of need for a payee because, in addition to spending substantial amounts of money on substances of abuse, they reported either difficulty meeting basic material needs or substantial harm from substance use. RESULTS: Of 290 patients surveyed, 78 (27 percent) met level 1 criteria. Altogether, 35 patients (45 percent of level 1 patients and 13 percent of all surveyed patients) met the more specific level 2 criteria, indicating that they were likely to be in need of a payee. As expected, veterans who met the level 2 criteria were more likely than those meeting only the level 1 criteria to have both self-rated and clinician-rated difficulties managing money. However, clinicians did not rate these veterans as more likely to benefit from a payee. CONCLUSIONS: A substantial proportion of veterans who have not been assigned a payee may need one. More effective approaches to money management in this population are needed.

Possession of a large amount of money is a well-recognized trigger for substance abuse relapse (1,2), and it has been asserted that unrestricted access to public support payments may increase the risk of such a relapse (3). Among cocaine users with schizophrenia, increases in cocaine use and psychiatric symptoms around the beginning of each month, coincident with receipt of disability payments, have been reported (4).

Mismanagement of public support payments such as Social Security or veterans benefits is grounds for assignment of a payee to prevent funds from being misused. Both the Social Security Administration (5) and the Veterans Benefits Administration of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) (6) assign payees to beneficiaries who are deemed incapable of managing their own benefits, usually because of an organic brain syndrome or psychosis. In these cases, the beneficiary's benefits checks are mailed directly to representative payees, who are responsible for ensuring that funds are spent in the beneficiary's best interest.

In this paper, we define three screening criteria, referred to as level 1 criteria, for determining when patients may need a payee. The criteria are met when a patient receives public support payments, does not have a payee, and has a substance abuse diagnosis. In a previous paper, we proposed three more specific criteria, referred to as level 2 criteria, for identifying patients who are incapable of managing their funds because of an addictive disorder (7). Payee assignment was deemed appropriate if within the previous 12 months the beneficiary demonstrated a maladaptive pattern of substance use and the mismanagement of funds had been manifested by either an inability to meet basic needs (criterion 2A) or substantial harm to the recipient (criterion 2B). An additional level 2 criterion—the availability of a suitable payee—was not evaluated in this study.

For this study, we developed a questionnaire that operationalized the criteria for payee assignment and used it to assess the possible need for payees among psychiatric inpatients. A survey of VA psychiatric inpatients was designed to answer six questions. What proportion of hospitalized veterans meet level 1 screening criteria, in that they have unmonitored spending of public support payments and a diagnosis of substance abuse? What proportion of these level 1 patients may be in need of a payee by the more specific level 2 criteria described above? What characteristics distinguish patients who meet level 2 criteria from patients who meet only level 1 criteria? Do patients who meet level 2 criteria differ from patients who meet only level 1 criteria in their own or their inpatient clinicians' assessment of whether or not they mismanage their funds? Do patients who meet level 2 criteria differ from patients who meet only level 1 criteria in their own or their inpatient clinicians' assessment of whether a payee would help? Would level 1 or level 2 patients agree to have their funds managed for them?

Methods

Sample

A sequential sample of veterans hospitalized in inpatient psychiatry units at VA medical centers was approached and invited to participate in a survey. The four centers were in West Haven, Connecticut; Northampton, Massachusetts; Bedford, Massachusetts; and Los Angeles. In all, 570 veterans were identified—150 at each of the first three sites and 120 at the fourth site. Inpatients rather than outpatients were studied because, by virtue of their severe dysfunction, they were likely to include a high proportion of patients in need of a payee. Data were collected between January and May 2000.

Data collection

First, sequential inpatients were asked to complete a study survey (described below) that dealt with how they managed their funds. Second, the treating inpatient clinicians of all identified patients were approached and asked to complete a brief questionnaire that addressed the same issues as the patient survey. Patient age and demographics and diagnostic information were obtained from chart review.

Research assistants administered the patient questionnaire after patients had reviewed and signed an informed consent form explaining that this was a voluntary survey being conducted for research purposes only. The study was approved by each of the local institutional review boards.

Measures

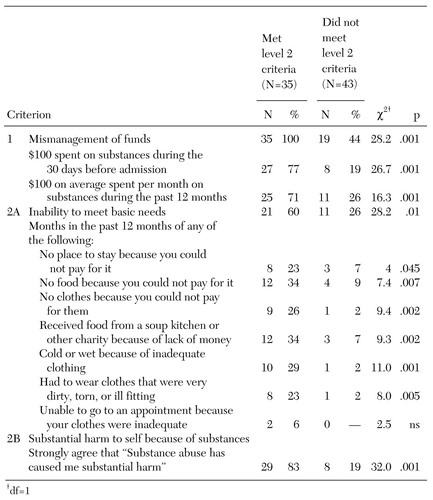

The questionnaires contained items aimed at determining which patients with substance abuse diagnoses were in greatest need of a payee by level 2 criteria (Table 1). These questions are detailed below in the discussion of level 2 criteria.

Data on patient characteristics were obtained that might account for differences between patients in need of a payee and other patients. These data included patients' sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric status, income, and expenditures.

Questions on substance use and expenditures for substance abuse were extracted from the drug and alcohol modules of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), Version 5 (8). Questions in the ASI referring to substance use during the past 30 days were reworded to reflect the 30 days before admission in this hospitalized sample. Composite scores reflecting overall severity of alcohol use and drug abuse, respectively, were computed from the ASI subscales, using standard formulas (9).

Questions on patients' attitudes toward their management of funds asked whether the patients believed they had difficulty managing their funds, whether the patients thought a payee would be helpful, and whether the patients wanted someone to manage their funds. A 4-point Likert scale (1, strongly disagree; 2, somewhat disagree; 3, somewhat agree; 4, strongly agree) was used to assess these attitudes.

The clinician questionnaire was briefer and solicited background information about the patients' psychiatric and substance abuse diagnoses and presented Likert-scaled items addressing the patients' money management capacities. These items were reworded from the patients' questionnaire to reflect clinicians', rather than patients', assessments of the patients' management of their funds.

Level 2 criteria

It was considered that recipients of public support payments with a current diagnosis of substance abuse and no current payee might need a payee if they met the criteria described above (Table 1). The level 1 criteria about mismanagement of funds was operationalized as the patient's having spent at least $100 on drugs or alcohol during the 30 days preceding hospitalization or as the patient's having spent an average of $100 per month during the 12 months preceding hospitalization. The level 2 criteria addressed two adverse consequences of substance abuse. Criterion 2A was that the patient had not met basic needs in at least two of the past 12 months. Criterion 2B was that the patient strongly agreed with the statement "Substance use has caused me substantial harm."

These criteria were not expected to determine definitive need for a payee; they were expected to determine possible need for a payee, subject to further clinical assessment.

Data analysis

Data analysis proceeded in several steps. First, the above criteria were applied to identify patients who met the level 2 criteria, and then this group and the group meeting only the level 1 criteria were compared on the items used to operationalize the criteria.

Second, the two groups were compared on additional sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, on patterns of income and expenditures, and on habits of and attitudes toward personal funds management. For items asked of both patients and inpatient clinicians, the results were compared to determine the agreement between patient and clinician responses.

Comparisons were conducted using t tests for continuous variables and chi square tests for categorical variables. First, Likert-scaled items were dichotomized to differentiate any agreement from any disagreement, and chi square tests were used to compare level 2 patients with patients meeting only level 1 criteria on these dichotomized variables. Pearson's product-moment correlations were used to determine the strength of associations between clinician and patient assessments of the need for and the benefits of money management. Paired t tests were conducted to determine whether patient and clinician assessments were significantly different from each other.

Test results were considered statistically significant when p values were less than .05, using two-tailed tests. Stand ard errors of the mean are reported.

Results

The sample

A total of 570 sequentially admitted psychiatric inpatients were identified through administrative records. The clinician questionnaire was completed for 504 inpatients (88 percent). A total of 290 (57 percent of the 504 patients) completed the patient questionnaire. Of the 214 patients who did not complete the questionnaire, 89 (42 percent) were discharged from the inpatient unit before being asked to participate, 89 (42 percent) refused to participate, and 36 (17 percent) were judged to be too impaired to be interviewed because they could not answer three screening questions indicating competence to give consent.

Patients who completed the surveys were compared with noncompleters, for whom only clinician surveys were available. Patients who completed the survey were slightly but significantly older (mean±SD age, 51.2±11.6 years compared with 49.4±10 years; t=2.2, df=472, p<.05), more likely to have been diagnosed as having a personality disorder (19 percent versus 12 percent; χ2=4.6, df=1, p<.05), and more likely to be receiving public support payments (57 percent compared with 48 percent; χ2=3.9, df=1, p<.05). No differences were found on any other sociodemographic or clinical measures.

Of the 290 patients for whom we had both patient and clinician survey data, 175 (60 percent) were receiving public support payments, and 104 of these recipients (59 percent) had a substance abuse diagnosis; 78 (75 percent) of the 104 did not already have a payee, fiduciary, or conservator. The sample of interest for this paper thus consisted of the 78 patients (27 percent of all respondents) who met level 1 criteria: they were receiving public support payments, had a substance abuse diagnosis, and had not been assigned any kind of payee.

Level 2 criteria

A large percentage (45 percent) of the 78 patients who met level 1 screening criteria also met the more specific level 2 criteria for needing a payee. As Table 1 shows, the percentages of patients who endorsed individual items for criterion 2A were far greater among level 2 patients than among level 1 patients. In fact, level 2 patients were significantly more likely to endorse all but one of the individual items.

There was significant variation across facilities in the proportion of veterans who met level 1 criteria. Only 13 percent of the surveyed patients at the Los Angeles center and 19 percent at the Bedford center were identified as possibly needing a payee, in contrast to 36 percent and 32 percent at the West Haven and the Northampton centers, respectively (χ2=14.5, df=3, p<.01). However, the proportions of level 1 patients meeting the level 2 criteria did not differ significantly by site.

Demographic, psychiatric, and substance abuse variables

As would be expected from a sample of veterans, nearly all of the 78 patients were male (73 patients, or 94 percent). Their mean±SD age was 50±8.8 years. The majority (54 patients, or 69 percent) were Caucasian, and few (ten patients, or 13 percent) were married. In addition to substance abuse diagnoses, patients had a variety of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. Twenty patients (26 percent) were diagnosed as having schizophrenia; 13 (17 percent), bipolar disorder; 33 (42 percent), depression; 21 (27 percent), personality disorder; and 18 (23 percent) posttraumatic stress disorder (percentages total more than 100 percent because some of the patients had more than one psychiatric diagnosis). The only characteristic that differed by need for a payee was depression, which was a less common diagnosis among patients needing a payee (29 percent compared with 54 percent, χ2=4.9, df=1, p<.03). Composite ASI drug use severity scores were significantly higher among patients possibly in need of a payee (composite drug index, .16 versus .05; t=10.6, df=1, p<.001); alcohol use severity scores were not significantly higher for patients possibly in need of a payee (composite alcohol index, .39 versus .29; t=2.7, df=1, p<.11).

Income and expenditures

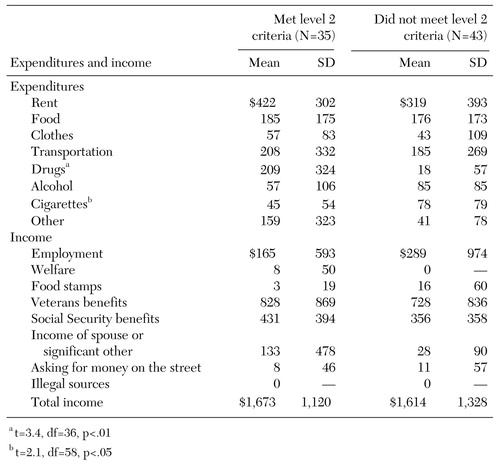

As shown in Table 2, during the 30 days before admission, patients who met the level 2 criteria did not differ from patients who met only the level 1 criteria in total income, income from specific sources, total expenditures, or expenditures in any category other than drugs and cigarettes (Table 2). Thus differences between the two groups in their ability to manage their funds were not attributable to differences in total income, and there were no significant differences in nondrug expenditures.

Money management assessments

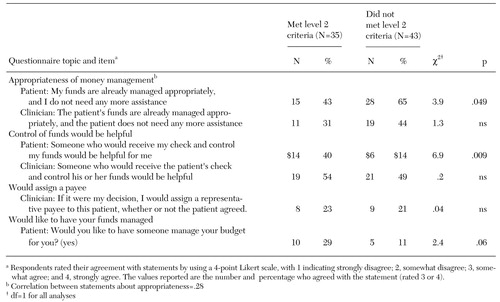

As shown in Table 3, patients who met the level 2 criteria were significantly more likely than patients who met only the level 1 criteria to feel that they had money management difficulties and to be assessed by their clinicians as having money management difficulties. Level 2 patients were also significantly more likely to feel they would benefit from having a payee. However, their clinicians were not more likely to rate them as likely to benefit from having a payee. Thus, some level 2 patients were rated by their clinicians as having money management difficulties but as not being likely to benefit from having a payee. Relatively few patients (13 patients, or 19 percent of all at-risk patients) wanted someone to receive their checks and manage their finances for them.

Given that clinicians were not more likely to rate level 2 patients as more likely to benefit from money management than other patients, it is not surprising that clinicians were not more likely to think assigning a payee to these patients would be helpful. However, it is noteworthy that a clinician's willingness to assign a payee depended heavily on whether the patient would agree to have a payee. Whereas only 23 percent of the clinicians (N=17) would assign a payee whether or not the patient agreed, 57 percent (N=40) favored assignment of a payee if the patient agreed.

Patient and clinician assessments

There were modest correlations between patient and clinician assessments of the extent of overall money management problems. The correlation between patient and clinician ratings of whether funds "are already managed appropriately," although significant, was only .28. The correlation between patient and clinician opinions about the potential value of a payee was not significant.

In general, clinicians were more likely than patients to identify money management difficulties. Clinicians were significantly less likely than patients to agree with the statement "The patient's funds are already managed appropriately" (38 percent versus 55 percent; t=2.2, df=77, p<.04) and were more likely than patients to agree with the statement "Someone who would receive the patient's check and control his/her funds would be helpful" (51 percent versus 26 percent; t=3.4, df=77, p<.001).

Discussion

Findings

We surveyed 290 veterans hospitalized in VA psychiatric units to identify patients who might be in need of a payee because of their substance abuse. A strikingly high proportion, 27 percent, were found to possibly need a payee because they were receiving public support payments, did not have a payee, and had a substance abuse diagnosis. This proportion was three times as great as the proportion of public support recipients in the sample with a substance abuse diagnosis who had already been assigned a payee (9 percent).

There was only modest differentiation between the patients who met the more specific level 2 criteria and those who met only the level 1 criteria. A significantly larger proportion of level 2 patients identified themselves as having difficulty managing their money and as being likely to benefit from being assigned a payee. However, the differentiation between level 1 and level 2 patients was less clear in the clinicians' ratings. Clinicians identified a higher proportion of level 2 patients than level 1 patients as having difficulty managing their funds. However, they did not think interventions would be any more effective for the level 2 patients than for the level 1 patients.

In absolute percentages, the level 2 patients indicated considerable money management distress. A full 57 percent did not think that they managed their funds appropriately. A somewhat smaller percentage, 40 percent, thought someone who would control their funds would be helpful. An even smaller percentage, 29 percent, actively wanted someone to manage their budget for them. Clinicians also identified high proportions of patients with money management difficulties and a need for intervention. The clinicians of 69 percent of level 2 patients did not think that their patients managed their funds appropriately; for 56 percent of these patients, the clinicians thought it would be helpful for them to have someone else control their funds.

Implications of findings

Our finding that a substantial number of hospitalized patients with a substance abuse diagnosis have money management difficulties has two important implications. First, it suggests that capacity to manage money should be routinely assessed among inpatients who do not have payees, because a substantial number will need assistance in managing their funds.

Second, and perhaps of greater importance, there is a need for demonstrably effective interventions that can address patients' need for money management assistance. Thus far no models of money management have demonstrated empirical effectiveness. However, retrospective studies of patients in selected institution-based payee programs suggest that the psychiatric status of the patients in these programs is better than the psychiatric status of comparison groups (10,11), and considerable benefits have been reported in selected cases (12). There may also be a place for services that do not have the involuntary features of payeeship but involve managing patients' funds collaboratively with them.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study deserve comment. First, we have not formally assessed the reliability and validity of our survey instrument. For example, multiple inquiries about recent harm from drug use might more validly capture the concept of substantial harm from drugs than our single patient-rated item. The construct "need for a payee" is inherently difficult to validate, because there is no readily available standard for these determinations. However, the low levels of agreement between clinician and patient ratings suggest that concurrent validity needs to be better established, perhaps by surveying other informants, such as patients' significant others, to determine agreement about funds management.

A second limitation concerns the generalizability of our findings. The population surveyed in this study was limited to veterans hospitalized at four VA medical centers. As a result, almost all the participants were male. The generalizability of the study findings to women, outpatients, and other community settings is unknown.

It is also possible that the 57 percent of patients who consented to be interviewed differed in a systematic way from those who did not consent to be interviewed. Although possible, this seems unlikely because only relatively small differences were found between the surveyed and nonsurveyed patients, and the differences do not suggest any substantial selection bias.

Conclusions

A substantial number of hospitalized inpatients may need assistance in managing their funds. Effective approaches to money management in this population are needed.

Acknowledgments

This project was a multisite collaboration among the following: VA Connecticut Healthcare System (Susan Harman. B.A., and Rhonda Pruzinsky, B.A.), Bedford VA Medical Center (Charles Drebing, Ph.D., and Alice Van Ormer, M.A.), Northampton VA Medical Center (Christopher Cryan, B.A., and Lynn Gordon, R.N.), and the West Los Angeles VA Medical Center. This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs VISN 1 and VISN 22 Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Care Center at the Northeast Program Evaluation Center in West Haven, Connecticut.

Dr. Rosen is associate professor of psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Rosenheck is professor of psychiatry and public health and director of the division of mental health services and treatment outcomes research in the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Shaner is associate director of mental health for the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System and professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the School of Medicine of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Dr. Eckman is associate professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine and program director of the dual diagnosis treatment program at the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Dr. Gamache is adjunct assistant professor and senior postdoctoral research associate at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Mr. Krebs is a research associate and clinician at the Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial Veterans Hospital in Bedford, Massachusetts, and is also affiliated with the Bedford branch of the New England Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center. Send correspondence to Dr. Rosen at the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System, Department of Psychiatry, 116A, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Veterans Affairs inpatients who met two levels of criteria for having a potential need for a representative payee

|

Table 2. Mean income and expenditures during the 30 days before hospital admission of Veterans Affairs inpatients who met two levels of criteria for having a potential need for a representative payee

|

Table 3. Patient and clinician assessments of patients' ability to manage funds among Veterans Affairs inpatients who met two levels of criteria for having a potential need for a representative payee

1. Wallace BC: Treating crack cocaine dependence: the critical role of relapse prevention. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 24:213-222, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. O'Brien CP, Childress AR, McClellan T, et al: Integrating systemic cue exposure with standard treatment in recovering drug-dependent patients. Addictive Behavior 15:355-365, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Satel S: When disability benefits make patients sicker. New England Journal of Medicine 33:794-796, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Shaner A, Eckman TA, Roberts LJ, et al: Disability income, cocaine use, and repeated hospitalization among schizophrenic cocaine abusers: a government sponsored revolving door? New England Journal of Medicine 333:777-783, 1995Google Scholar

5. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 20: Employees' Benefits, Chapter 416 Supplemental Security Income for the Aged, Blind, and Disabled, Subpart F: Representative Payment, 416.610Google Scholar

6. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 38: Pensions, Bonuses, and Veterans' Relief, Chapter 1: Department of Veterans Affairs, Part 3: Adjudication, 3.353Google Scholar

7. Rosen MI, Rosenheck RA: Substance abuse and the assignment of representative payees. Psychiatric Services 50:95-98, 1999Link, Google Scholar

8. McClellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:199-213, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Alterman AI, Brown L, Zabahero L, et al: The interviewer severity ratings of the ASI: a further look. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 34:201-209, 1984Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Ries RK, Comtois KA: Managing disability benefits as part of treatment for persons with severe mental illness and comorbid drug/alcohol disorders: a comparative study of payee and non-payee participants. American Journal of Addictions 6:330-338, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

11. Luchins DJ, Hanrahan P, Conrad KJ, et al: An agency-based representative payee program and improved community tenure of persons with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:1218-1222, 1998Link, Google Scholar

12. Brotman AW, Muller JJ: The therapist as representative payee. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:167-171, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar