A Comparison of Guidelines for the Treatment of Schizophrenia

Abstract

Although the clinical and administrative rationales for the use of guidelines in the treatment of schizophrenia are convincing, meaningful implementation has been slow. Guideline characteristics themselves influence whether implementation occurs. The authors examine three widely distributed guidelines and one set of algorithms to compare characteristics that are likely to influence implementation, including their degree of scientific rigor, comprehensiveness, and clinical applicability (ease of use, timeliness, specificity, and ease of operationalizing). The three guidelines are the Expert Consensus Guideline Series' "Treatment of Schizophrenia"; the American Psychiatric Association's "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia"; and the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. The algorithms are those of the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP). The authors outline the strengths of each and suggest how a future guideline might build on these strengths.

In the past decade, practice guidelines have been developed for the treatment of many chronic illnesses, including schizophrenia. Guidelines are designed to assist practitioners in making appropriate health care decisions by synthesizing the treatment literature into a usable form and facilitating the transfer of research into practice. Guidelines have also been used to control practice variation, to lower costs, and to evaluate care processes (1,2).

Despite the tremendous promise of treatment guidelines, however, implementation has been difficult to achieve (3). Guideline characteristics, such as clarity, complexity of treatment recommendations, perceived credibility, and organizational sponsorship, have been shown to affect clinicians' acceptance of guidelines (3,4,5). The Institute of Medicine task force described a "good" guideline as one that has validity, reliability, reproducibility, applicability, clarity, scheduled review, good documentation, and multidisciplinary input (6).

Comparison of guidelines

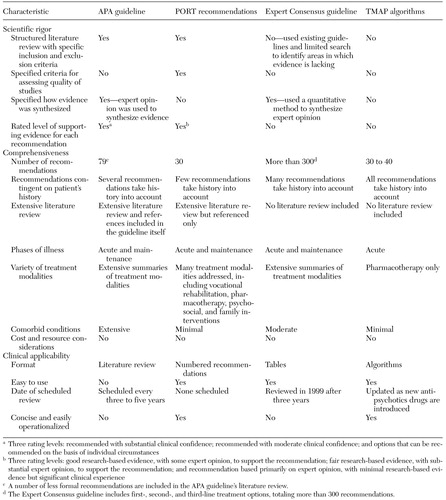

To compare characteristics that are likely to affect implementation, we examined three nationally prominent practice guidelines and one set of algorithms: the Expert Consensus Guideline Series' "Treatment of Schizophrenia" (7), the American Psychiatric Association's (APA) "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia" (8), the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations (9), and the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) algorithms (10). We compared them on degree of scientific rigor, comprehensiveness, and clinical applicability.

We believe this comparison will assist the decision-making process for practitioners and health care organizations that are considering the implementation of guidelines and will inform the development of future guidelines.

Scientific rigor

Guidelines developed with a high degree of scientific rigor are likely to be valid, reliable, and reproducible. Ideally, guideline developers should specify treatment questions, conduct an extensive structured literature search, assess the quality of the studies identified in the search, report how the studies synthesized the scientific evidence, make key data available for readers, and label the strength of the evidence for each treatment recommendation.

The guidelines produced by APA and by PORT are the most scientifically rigorous of those we examined. The developers of these guidelines conducted extensive structured literature reviews and considered study design and quality in making their recommendations. They also coded each recommendation to indicate the strength of the supporting evidence and included a list of references. However, neither set of developers published formal evidence tables, and only PORT specified how expert review was incorporated into the final guideline.

The developers of the Expert Consensus guideline and of the TMAP algorithms conducted limited literature searches and did not code recommendations to indicate the level of supporting evidence. Indeed, the Expert Consensus guideline was developed specifically to provide assistance to clinicians in areas in which scientific evidence was weak or lacking.

Comprehensiveness

Comprehensive guidelines for the treatment of schizophrenia address more phases of the illness, discuss a wider variety of treatment modalities, and make greater numbers of specific recommendations. They also have greater depth, with recommendations reflecting previous treatment trials and responses. Ideally, costs and resource allocation are also considered.

Literature review. The APA guideline has the most comprehensive literature review, with an extensive text summary of the treatment literature and an exhaustive list of references. The PORT guideline references detailed review articles, whereas the Expert Consensus guideline and the TMAP algorithms include only limited literature reviews and selected references.

Number and depth of recommendations. The APA and Expert Consensus guidelines make the most specific treatment recommendations, and PORT makes the fewest. Only a minority of the APA and PORT recommendations are contingent on a patient's treatment history. In contrast, the recommendations listed in the TMAP algorithms are based exclusively on the patient's treatment and response history.

Phases of the illness. The APA, PORT, and Expert Consensus guidelines include specific recommendations about treatment of the acute and maintenance phases of schizophrenia. TMAP indicates that its algorithms are suitable for "any patient beginning medication treatment or taking a medication without a satisfactory response."

Content. The APA guideline includes several recommendations about pharmacological management, group and individual therapy, vocational rehabilitation, and specific psychosocial interventions. The PORT recommendations focus mainly on pharmacotherapy, but recommendations are also made for family interventions, psychological interventions, vocational rehabilitation, and case management. The Expert Consensus guideline addresses both pharmacological and psychosocial interventions and offers recommendations about the intensity or location of nonpharmacological services. In contrast, the TMAP algorithms address only the pharmacological management of schizophrenia.

Costs. None of these guidelines include specific considerations about costs and resource allocation in their recommendations, although the APA guideline notes that the advantages of the newer antipsychotic medications should be balanced against their costs, the PORT recommendations refer to the costs of assertive community treatment and clozapine, and the Expert Consensus guideline includes a policy section that recommends interventions to increase the cost-effectiveness of mental health services.

Clinical applicability

Ease of use. The algorithmic format employed by TMAP makes it the easiest to use. The Expert Consensus guideline, designed to be user-friendly, lists recommendations in tabular form. The numbered PORT recommendations are quickly assimilated. The APA guideline, written in the form of a literature review, is more difficult to assimilate and use.

Timely review. The APA guideline, published in 1997, was based on reviews of the scientific literature up to 1995. Revisions are scheduled at three- to five-year intervals. The PORT was based on literature reviews up to 1993, and no revisions are scheduled. The Expert Consensus guideline was originally published in 1996 and was updated in 1999. TMAP revisions are made available at the TMAP Web site as new antipsychotic agents are introduced; the latest revision occurred in December 1999.

Specificity or ease of operationalizing. Guidelines that are specific and can be operationalized as rate-based monitors lend themselves to benchmarking and the establishment of best-practice parameters. Both the TMAP algorithms and the PORT recommendations are explicit, specific, and easily operationalized. The Expert Consensus guidelines are more general, and the APA guidelines are almost didactic in format, making them more difficult to operationalize.

Discussion

An ideal guideline for the treatment of schizophrenia would combine the best features of each of these efforts. It would be derived from a comprehensive literature review and would explicitly assess the quality of supporting research studies and the methods used for synthesizing evidence. Evidence tables would be constructed and published. Although both evidence-based and expert opinion would be incorporated, there would be a clear delineation between the two.

The ideal guideline would make recommendations not only for the pharmacological management of schizophrenia but also for assessment and psychosocial interventions during both the acute and the maintenance phases of the illness. Treatment recommendations would take into account important demographic, clinical, and psychosocial issues. Cost considerations would be included. Recommendations would be summarized in a concise, user-friendly format, and suggestions would be made about how the guidelines might be operationalized as quality monitors. Guidelines would be revised at three-year intervals.

Guidelines that address the factors described in this review may be more effective in changing practices. However, even excellent guidelines will require additional support, such as academic detailing and provider reminders, if best practices are to be widely disseminated.

The authors are clinical assistant professors in the department of psychiatry of the University of Michigan Health System, B1D102, UH, University of Michigan Health System, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-0020 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Valenstein is also affiliated with the Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center for Excellence.

|

Table 1. Comparison of the American Psychiatric Association's "Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia," the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations, the Expert Consensus Guideline Series' "Treatment of Schizophrenia," and the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) algorithms

1. Margolis CZ: Solving clinical problems using clinical algorithms, in Implementing Clinical Practice Guidelines. Edited by Margolis CZ, Cretin S. Chicago, American Hospital Association Press, 1999Google Scholar

2. Smith TE, Docherty JP: Standards of care and clinical algorithms for treating schizophrenia. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 21:203-220, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Davis DA, Taylor-Vaisey A: Translating guidelines into practice: a systematic review of theoretic concepts, practical experience, and research evidence in the adoption of clinical practice guidelines. Canadian Medical Association Journal 157:408-416, 1997Google Scholar

4. Solbert LI, Brekke ML, Fazio CJ, et al: Lessons from experienced guidelines implementers: attend to many factors and use multiple strategies. Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement 26:171-188, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hayward RS: Clinical practice guidelines on trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal 156:1725-1727, 1997Google Scholar

6. Field MY, Lohr KN (eds): Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Agency. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, 1990Google Scholar

7. McEvoy JP, Scheifler PL, Frances A: The Expert Consensus Guidelines Series: treatment of schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 11):1-80, 1999Google Scholar

8. Herz MK, Liberman RP, Lieberman JA, et al: American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154 (suppl 4)1-63, 1997Google Scholar

9. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM, and the co-investigators of the PORT project: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Miller AL, Chiles JA, Chiles JK, et al: The Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) schizophrenia algorithms. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:649-657, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar