Characteristics of Suicide Attempts in a Large Urban Jail System With an Established Suicide Prevention Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention in Washington State, like many jail systems across the nation, implemented a suicide prevention program in response to high suicide rates. A review committee was formed to prospectively study the patterns of suicide attempts that occurred in the system after the program was implemented and to make recommendations for improvements. METHODS: All first suicide attempts per jail booking over a 33-month period in two of the department's jails were studied. For each attempt, characteristics of the individual and of the attempt were abstracted by trained staff. RESULTS: A total of 132 first suicide attempts were made by 124 individual inmates during the study period. The prevalence of mental illness among inmates who attempted suicide was 77 percent, compared with 15 percent in the general jail population. Seventy-five percent of the inmates who attempted suicide had received a mental health evaluation from jail personnel before the attempt. Suicide attempts that were made in observation units for suicidal inmates (42 percent of all attempts), particularly those made in group observation units, necessitated fewer visits to an emergency department than those that occurred in general areas of the jail. CONCLUSIONS: On the basis of these findings, the jails implemented interventions such as more suicide screening and treatment for inmates who have active substance abuse, greater consensus building in decisions about housing, and structural changes such as greater use of group-housing units and the use of barriers to prevent the inmates from jumping from balconies.

Suicide is the leading cause of death in U.S. jails (1). Although the precise rate of suicide in jails is controversial, estimates range from 47 to 114 per 100,000, which is nine to 14 times higher than the rate in the general population (2). Factors that make jails a particularly high-risk environment include the large proportion of inmates who have mental illness, the high rate of enforced withdrawal from alcohol and drugs, and the traumatic effect that criminal conviction and incarceration have on an inmate's personal life. Furthermore, the transient nature of the jail population adds complexity to the identification of high-risk individuals (2,3,4,5,6).

Over the past decade, growing attention has been paid to the effectiveness of suicide prevention programs in jails. Studies have documented reductions in the number of suicide attempts and deaths in systems in which prevention programs have been implemented (1,2,4). The King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention in Washington State adopted a suicide surveillance and prevention program in 1991. The prevention program, consistent with other programs described in the literature, includes training for correctional officers and health professionals, intake screening, psychiatric evaluation for at-risk inmates, communication among staff, special safe-housing units, observation of inmates by officers, medical intervention procedures, and a review of completed suicides (3,6,4). These efforts have helped reduce the number of suicide deaths in this jail system.

However, suicide attempts continue to occur. Such attempts, especially among individuals who were not prospectively identified as being at risk, pose a formidable challenge for jails, which are charged not only with keeping inmates safe but also with minimizing liability. As part of an effort to further improve the suicide prevention program, a quality improvement committee was formed in the Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention to examine the characteristics of inmates who attempted suicide in the county jail system and to make recommendations for actions to be taken. This article summarizes the major findings from that process.

Methods

Setting

The King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention manages several correctional facilities in King County, Washington, the two largest of which are the King County Correctional Facility in downtown Seattle and the Regional Justice Center in the city of Kent in south King County, which was opened in April 1997. Both facilities are accredited by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care. About 60,000 individuals are booked into the two jails each year. The average daily population increased from 1,875 in 1996 to 2,266 in 1999. Most of the inmates housed in these facilities have been charged and are awaiting or undergoing trial, have been convicted and are awaiting sentencing, or are serving sentences of up to a year. A small proportion of inmates are held while awaiting transfer to other facilities.

Medical staff are available 24 hours a day at both jails. Although most direct patient care occurs at on-site clinics, the jails have special units for inmates who are mentally ill, who are under suicide observation, or who need acute medical services, including treatment for problematic alcohol or drug withdrawal. Inmates who experience life-threatening emergencies or who need specialized medical services are referred to one of two local hospitals.

As each inmate is booked into jail, health-trained correctional staff members use an intake screening form to obtain medical, psychiatric, substance abuse, and pregnancy histories. Any inmate who is found to have a psychiatric history or psychiatric symptoms, who is found to have significant health complaints, or who appears to be disoriented, agitated, or obtunded is referred immediately to medical personnel. On the basis of this initial screening procedure, about 15 percent of all inmates are referred to the jail's psychiatric staff for a mental health evaluation.

Master's- or doctoral-level psychiatric evaluation specialists or trained psychiatric nurses are available 24 hours a day for the immediate evaluation of inmates who are identified as having mental health problems or who are exhibiting suicidal warning signs. The purpose of the evaluation is to assess the inmate's symptoms and to generate an accurate diagnostic impression that will guide therapeutic decisions.

Central to the evaluation is the completion of a standard form that includes detailed questions about psychiatric history and hospitalizations, questions about medications, and a thorough assessment of current and past suicidal behavior. The form also includes questions about drug and alcohol abuse, a detailed social history, and whether the inmate has a case manager. Finally, a mental status examination is performed. On the basis of these findings and a review of the inmate's medical record (if one exists), a diagnosis is made and a therapeutic plan implemented.

The principal decisions made at this juncture are whether the inmate requires housing in a special psychiatric unit for mental health reasons or because of suicidality or whether the inmate is a suitable candidate for placement in a general area of the jail. About half of inmates who are initially evaluated are housed in one of several mental health units, and the other half are considered fit to be housed in the general areas. Inmates who are housed in general areas are considered to have stable mental health conditions that are manageable through the jail's psychiatric clinic, and their risk of suicide is considered comparable to that of the general jail population.

About 27 percent of inmates housed in the psychiatric unit are under suicide observation, either in a group-housing unit or in an individual cell. Those who require housing in individual cells are checked on by a correctional officer at least every 15 minutes. Those who are housed in a group unit are in plain view of a correctional officer who is stationed about 20 feet away. On a regular basis, the mental health team reviews the cases of inmates who are under suicide observation to decide whether they need to continue in special housing or whether it is appropriate to move them to a general area. About half of the inmates who are initially placed under suicide observation are subsequently moved to a general area of the jail.

Data collection and analysis

Psychiatric staff at the two jails collected data on all suicide attempts during the 33-month period from October 1, 1996, to June 30, 1999. "Suicide attempt" was defined as any self-harm incident brought to the attention of medical staff that was linked with an inmate's expressed intent to commit suicide. We did not try to differentiate between "real" suicide attempts and "gestures" (manipulative, attention-getting acts) as defined in a 1984 Special Commission on Detention Suicides in Massachusetts (7), because there is evidence that the characteristics of inmate behavior are similar between lethal and nonlethal attempts (8) and that the presence of a manipulative component does not distinguish life-threatening events from medically insignificant ones, especially among incarcerated persons (7).

After each suicide attempt, psychiatric staff at the two jails collected data from the inmate's medical record and officers' logs. Basic demographic information; medical, psychiatric, and substance abuse history; housing status; characteristics of the suicide attempt; and whether transportation to a hospital emergency department was required were abstracted and entered into a Microsoft Access database and analyzed with SPSS, version 7.5.1. Only first attempts during a single incarceration episode were included in the analysis to avoid the bias associated with the small number of inmates who made multiple attempts during an incarceration.

The primary analysis consisted of a comparison of the characteristics of inmates and suicide attempts by suicide observation status: inmates who had received a psychiatric evaluation before the attempt and who were under suicide observation at the time of the attempt; inmates who received a psychiatric evaluation before the attempt but who were not under suicide observation at the time of the attempt; and inmates who had not received a psychiatric evaluation before the attempt and who thus were not under suicide observation at the time of the attempt. Patient identifiers were encoded before analysis. The study was approved by the University of Washington's institutional review board in December 2000.

Results

Between October 1996 and June 1999, a total of 158 known suicide attempts were made in the King County Correctional Facility and the Regional Justice Center. The rate of suicide attempts in this series was calculated as 22 attempts per 1,000 average daily population per year, which was comparable to a rate calculated for the jails in South Carolina between 1985 and 1989 (9,10). The 158 attempts were made during 132 separate incarcerations by 124 individual inmates. Nineteen inmates (15 percent) accounted for 34 percent of all attempts. The subsequent analysis was restricted to the 132 first attempts made during an incarceration.

During the study period, two suicide deaths occurred. In both cases the inmates were known to be at high risk of suicide and were under suicide observation at the time of the incident. One inmate had made repeated threats over many months but had not made any actual suicide attempts until the one that resulted in death. Because this was a first attempt during the incarceration, it was included in the analysis. The second inmate had made an attempt several days before the completed suicide. Only the first, nonfatal attempt was included in the analysis.

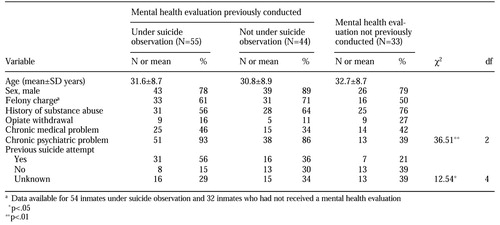

Table 1 summarizes the demographic, clinical, and other characteristics of the inmates who attempted suicide. The average age of inmates who attempted suicide was 31.5±8.7 years. Eighty (61 percent) of the 132 incarcerations involved a felony charge. These characteristics were not significantly different from those of the general jail population, for whom the average age was 29.5 years and of whom 64 percent had been charged with a felony. Women constituted a higher proportion of inmates who attempted suicide (24 inmates, or 18 percent) than of the general jail population (12 percent).

Inmates who attempted suicide were much more likely to have a chronic psychiatric problem than inmates in the general jail population (102 inmates, or 77 percent, compared with 15 percent). However, the proportion of inmates with a chronic medical condition (54 inmates who attempted suicide, or 41 percent, compared with 40 percent in the general jail population) or a history of substance abuse (84 inmates, or 64 percent, compared with 60 percent) was similar. Fifty suicide attempts (38 percent) occurred within three days of incarceration, and 37 (28 percent) occurred more than 30 days after incarceration. Only 14 percent of inmates in the general jail population stayed in jail longer than 30 days.

Fifty-five of the 132 suicide attempts (42 percent) were made by inmates who were under formal suicide observation at the time of the attempt. The remaining 77 attempts (58 percent) were made by inmates who were housed in a general area of the jail. No significant differences were noted in age, sex, or type of charge between the three suicide observation categories.

Inmates who had not received a psychiatric evaluation before their suicide attempt and therefore were not candidates for suicide observation tended to have higher rates of substance abuse and opiate withdrawal than those who had received a psychiatric evaluation, although these differences were not significant. Among the inmates who had received no psychiatric evaluation before their suicide attempt, 39 percent had a chronic psychiatric problem, a rate far greater than that found in the general jail population (15 percent). In the course of psychiatric evaluations of these individuals after they attempted suicide, about 21 percent were found to have made a previous suicide attempt.

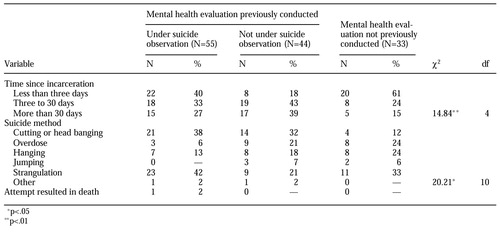

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the 132 suicide attempts. Forty percent of attempts made by inmates who were housed in a suicide observation unit occurred within the first three days of incarceration. In the case of inmates who received a mental health evaluation before their suicide attempt but who were not under suicide observation, only 18 percent of attempts occurred within the first three days, which suggests that this group of inmates were in fact at lower risk. In contrast, for inmates who had not previously received a mental health evaluation, 61 percent of the attempts occurred during the first three days. Inmates who were under suicide observation made fewer attempts by overdose, hanging, and jumping from a second-floor balcony than those who were not under observation, which probably reflects differences in the availability of self-harm options.

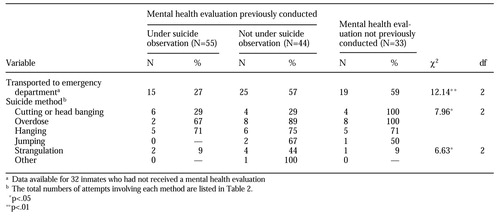

The suicide method in attempts that led to transportation to a hospital emergency department, along with statistics indicating the relationship between them, are detailed in Table 3 for each suicide observation category. Attempts that were made in an observation unit were associated with a significantly lower rate of transportation to an emergency department than attempts that were made in a general housing area.

To examine the relationship between suicide attempts and isolation units, we restricted the analysis to inmates who were under formal suicide observation at the time of their suicide attempt. During the study period, these inmates were housed in one of two ways. About a third of all suicidal inmates were housed in a group observation unit, and the remaining two-thirds were housed in isolation units where a correctional officer performed a visual check at least every 15 minutes.

Of the 55 attempts made by inmates who were under suicide observation, seven (13 percent) were made by inmates who lived in group housing, and 48 (87 percent) were made by inmates who were in isolation units. Only one (14 percent) of the seven attempts in the group observation unit resulted in transportation to the emergency department, whereas 14 (29 percent) of the 48 attempts that occurred in the isolation cells necessitated transportation to the emergency department.

Discussion

The characteristics of the suicide attempts in this study differed from those in studies that used data collected in the 1980s. These older studies showed that suicidal inmates in jails and lockups tended to be younger white men without psychiatric histories who were intoxicated when they were arrested for minor charges and who committed suicide by hanging within the first 24 hours of incarceration (3,6,11). The findings of more recent studies of suicide in urban jails have been consistent with our findings—that is, that chronic mental illness is common among inmates who attempt suicide and that the timing of their attempts ranges from days to months after incarceration (1,2,4,12). These differences may reflect a growing proportion of inmates who are mentally ill (13) or may be the result of suicide prevention programs that are better able to prevent early suicide attempts or of differences in the environments (jails versus lockups) that have been documented in the literature (2,3,14).

This review of consecutive suicide attempts showed that a majority of at-risk inmates at these urban jails were successfully identified, screened, and triaged. The mortality rate associated with suicide attempts was well below published norms for jails that do not have prevention programs (3) and was comparable to the rate observed in New York State, which has a well-documented suicide prevention program (4). Despite these encouraging findings, this process highlighted the persistence of a high-risk and vulnerable population of individuals entering the jails and identified opportunities for continued improvement.

Of major concern is the finding that 25 percent of the inmates who attempted suicide had not received a mental health evaluation. About 40 percent of these inmates had a psychiatric history, and a disproportionately large number had active substance abuse. Targeting services for this group of individuals is extremely difficult; by definition, they do not identify themselves as suicidal and generally do not exhibit disturbing behavior before they attempt suicide.

To better identify and manage this group of suicidal inmates, three significant interventions have been put in place. First, there has been a greater effort to conduct mental health screenings for persons who are intoxicated or experiencing withdrawal. Second, efforts have been made to improve communication between local mental health providers and jail health providers, primarily through greater use of telephone- and fax-based notification systems. Finally, new policies that allow the use of methadone maintenance therapy have been promoted in response to the numerous medical, psychiatric, and behavioral consequences of enforced withdrawal from opiates on entry to the jails.

The use of methadone in the jail system represents a series of policy decisions that have required collaboration between public health and correctional officials, the jail health team, and local methadone maintenance services. Inmates with opiate addictions who elect to receive methadone while they are in jail will, at a minimum, not lose their place on the waiting list for methadone treatment centers, and some will be given priority status for services when they are released. These interventions have led to a heightened awareness among correctional and health staff of the connection between substance use and suicide risk.

We also noted that about a third of the inmates who attempted suicide had received a psychiatric evaluation but were not under suicide observation at the time of the attempt. To address this problem, efforts to improve the accuracy of the screening process have been pursued. These efforts have included a greater degree of team consensus in decisions about housing for inmates whose cases are challenging and an expansion of educational programs focused on suicide prevention in the jails.

In this study we also examined the role of isolation among these suicidal inmates. The literature is replete with observations on the value of housing suicidal inmates together or in proximity to inmate observation aides (1,3,15). Such arrangements arguably provide for additional observational capacity and create opportunities for much-needed social association. However, Felthous (14) has urged caution in examining the apparent relationship between isolation and suicides in jail on the grounds that causality cannot be confirmed.

Often isolation is the mechanism of choice for managing an already suicidal and self-destructive inmate. On balance, however, the existing literature and the findings of this study support the value of group-housing units for appropriate candidates. At the time of the study, it was possible to house a maximum of 20 suicidal inmates together. At the time of writing, capacity has been expanded to allow up to 33 inmates (23 men and ten women) to be housed, and further expansion is planned.

Finally, to address the problem of inmates' jumping off second-floor balconies, Plexiglas barriers have been erected in the areas of the jails in which suicidal inmates are housed or managed. These areas include the psychiatric housing units, the medical infirmary, and the clinic. This intervention should virtually eliminate the risk that inmates will jump during transportation or when cell doors are opened.

Conclusions

This study has outlined a series of steps taken by two urban jails to identify the characteristics of suicide attempts in a system that has an established suicide prevention program and to make improvements where possible. It is hoped that these interventions will enable the number and severity of suicide attempts to be reduced further. The interventions were achieved through a quality-improvement process involving collaboration between correctional and health care staff.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Art Wallenstein, Steve Thompson, and Barbara Hadley for their administrative support. They also acknowledge Becca King, R.N.C., Holly Wollaston, A.R.N.P., M.P.H., and Tissa Kemp-Brown for their participation in the quality-improvement review committee. Funding for the initiative and for manuscript development was made available through the King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention.

Dr. Goss is affiliated with the department of internal medicine of the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. He was formerly with Jail Health Services, Seattle-King County Department of Public Health, with which Ms. Peterson and Ms. Kalb are affiliated. Dr. Smith is with the King County Department of Adult and Juvenile Detention in Seattle. Dr. Brodey is with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the University of Washington School of Medicine and with Jail Health Services, Seattle-King County Department of Public Health. Send correspondence to Dr. Goss at Harborview Medical Center, 325 Ninth Avenue, Box 359780, Seattle, Washington 98104 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of inmates in 132 suicide attempts, categorized by the inmate's suicide observation status

|

Table 2. Characteristics of 132 suicide attempts, categorized by the inmate's suicide observation status

|

Table 3. Suicide attempts that necessitated transportation to an emergency department, categorized by the inmate's suicide observation status

1. Hayes LM: From chaos to calm: one jail system's struggle with suicide prevention. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 15:399-413, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Farmer KA, Felthous AR, Holzer CE III: Medically serious suicide attempts in a jail with a suicide prevention program. Journal of Forensic Sciences 41:240-246, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

3. Hayes LM: National study of jail suicides: seven years later. Psychiatric Quarterly 60 (1):7-29, 1989Google Scholar

4. Cox JF, Morschauser PC: A solution to the problem of jail suicide. Crisis 18:178-184, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. DuRand CJ, Burtka GJ, Federman EJ, et al: A quarter century of suicide in a major urban jail: implications for community psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1077-1080, 1995Link, Google Scholar

6. Winkler GE: Assessing and responding to suicidal jail inmates. Community Mental Health Journal 28:317-326, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Haycock J: Manipulation and suicide attempts in jails and prisons. Psychiatric Quarterly 60(1):85-98, 1989Google Scholar

8. Lester D, Beck AT, Mitchell B: Extrapolation from attempted suicides to completed suicides. Journal of Abnormal Psychiatry 88:78-80, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. McKee GR: Lethal vs nonlethal suicide attempts in jail. Psychological Reports 82:611-614, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Hill G: Jail inmates, by sex, held in local jails. Washington, DC, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1997Google Scholar

11. Jordan FB, Schmeckpeper K, Strope M: Jail suicides by hanging. American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology 8:27-31, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Marcus P, Alcabes P: Characteristics of suicides by inmates in an urban jail. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:256-261, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Lamb HR, Weinberger LE: Persons with severe mental illness in jails and prisons: a review. Psychiatric Services 49:483-492, 1998Link, Google Scholar

14. Felthous AR: Does "isolation" cause jail suicides? Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 25:285-294, 1997Google Scholar

15. Hayes LM: Controversial issues in jail suicide prevention, part 2: use of inmates to conduct suicide watch. Crisis 16:151-161, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar