Service Use and Health Status of Persons With Severe Mental Illness in Full-Risk and No-Risk Medicaid Programs

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The service use patterns and health status outcomes of Medicaid recipients with severe mental illness in a system that assigned full financial risk to managed care organizations through capitation and a system that paid for mental health care on a no-risk fee-for-service basis were compared. METHODS: With use of a quasi-experimental design, initial interviews (time 1) and follow-up interviews six months later (time 2) were conducted among 92 clients in the full-risk group and 112 clients in the no-risk group. Regression models were used to compare self-reported service use and health status between the two groups. RESULTS: Service use patterns differed between the two groups. When symptom severity at time 1 was controlled for, clients in the full-risk group were more likely to have received case management but less likely to report contact with a psychiatrist or to have received counseling than clients in the no-risk group. When health status at time 1 was controlled for, clients in the full-risk group reported poorer mental health at time 2 than clients in the no-risk group. When physical health status at time 1 was controlled for, clients in the full-risk group reported poorer physical health at time 2 than clients in the no-risk group. CONCLUSIONS: Capitation was associated with lower use of costly services. Clients with serious mental illness in the full-risk managed care system had poorer mental and physical health outcomes than those in the no-risk system.

Virtually every state in the United States now uses managed care techniques to control behavioral health costs for Medicaid recipients. Implementation of these strategies has proceeded in the absence of substantial information on the resulting quality of care and effectiveness of services (1). Advocates for persons who have severe mental illness have raised concerns about the application of cost-cutting techniques developed in the private sector for employed persons with acute illnesses to persons in Medicaid and other public-sector programs who have persistent serious mental illness (2). We wanted to compare the service use patterns of Medicaid recipients with serious mental illness in a full-risk (capitated) and a no-risk (fee-for-service) system of care and to determine whether the type of financial risk arrangement affected patients' health status.

Many state Medicaid agencies use capitation—the prepayment of an established fee per person for a defined benefit over a set period—to keep their costs predictable and limited. In some instances a single capitated payment is made to a managed care organization (MCO). In these ostensibly integrated plans, behavioral health care can be provided directly by MCO providers, by behavioral health professionals who are paid on a discounted fee-for-service basis, or even by a behavioral health MCO or another agency through a subcontract. In other cases, the state Medicaid agency can carve out the behavioral health benefit by making capitated payments directly to a behavioral health MCO.

Managed care programs that use capitated payments to transfer financial risk to for-profit entities that are responsible for the care of vulnerable populations are of particular concern. Specifically, the incentives of capitation to lower costs and limit service use may lead to worse outcomes for persons with severe mental illness, who often have multiple and intensive service needs.

State Medicaid agencies that pay for mental health care on a fee-for-service basis also use cost-control measures. Often an administrative services organization that is not contractually at financial risk provides utilization management, including prior authorization and concurrent review. Because the pressures to reduce service use are less severe in no-risk situations than under capitated contracts, utilization management alone is not likely to lead to serious adverse consequences for clients, although this area needs further study.

Several studies have shown that various managed care arrangements affect the use of Medicaid behavioral health services and Medicaid costs (3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10). One of the most consistent findings is that capitation lowers Medicaid costs by decreasing the use of expensive services, such as hospitalization, while promoting less expensive outpatient treatment. Relatively little is known about how the resulting patterns of service use affect patient outcomes. Some researchers who have compared the outcomes of persons with severe mental illness in capitated and fee-for-service systems have found no evidence that individuals have been harmed by prepaid care (10,11). However, in Utah researchers found a slightly lower rate of improvement in mental health status among persons with schizophrenia in a capitated plan than among those in a fee-for-service plan (12).

This article reports the results of a prospective cohort study undertaken as part of the Tidewater managed care study, which compared two organization and financing strategies for Virginia Medicaid recipients with serious mental illness. A managed care program in the Tidewater region that assigned full financial risk to MCOs through capitation was compared with a program in the Richmond region that paid for mental health care on a no-risk fee-for-service basis (13).

In the Richmond region (no-risk condition), a Medicaid primary care case management program was in operation at the time of this study. In this model of managed care, mental health services were carved out of the program and were provided on a fee-for-service basis. The primary care providers were not gatekeepers for access to mental health services. The state Medicaid agency contracted with an administrative services organization to provide utilization management, including prior authorization and concurrent review, for mental health services. The administrative services organization was not at financial risk.

In the Tidewater region (full-risk condition), Medicaid recipients were mandated to enroll in one of four health maintenance organizations (HMOs). The medical-psychiatric component of the Medicaid mental health benefit was prepaid with use of capitated contracts with the HMOs. The covered mental health services were inpatient hospitalization, psychiatric evaluation, medication management, and psychotherapy. We examined the HMO in the Tidewater region that had the largest market share—about 60 percent. This HMO developed a subcontract with a subsidiary behavioral health MCO to manage the covered mental health benefits.

The behavioral health MCO subcontracted with five local community mental health centers—known in Virginia as community service boards—to provide outpatient mental health services and paid these boards on a capitated basis. Community service boards serve essentially the same function as public community mental health centers—they represent the primary locus of nonhospital care for persons with serious mental illness. A network of local hospitals provided inpatient services. The behavioral health MCO paid these hospitals on a capitated basis, placing them at risk for the costs of inpatient treatment. By withholding a portion of the capitated payments if utilization goals were not met, the behavioral health MCO shared financial risk for inpatient services with the community service boards and the hospitals.

Under both the no-risk and the full-risk condition, case management and rehabilitation services for persons with serious mental illness were provided by community service boards on a no-risk fee-for-service basis under Virginia's Medicaid state plan option. Under state law, only community service boards were eligible for Medicaid payments for state plan option services. Substance abuse services were not covered under the Virginia Medicaid program; these services were supported by block grant funding from the Virginia Department of Mental Health to the community service boards.

Methods

This prospective cohort study used a quasi-experimental design. Whether a subject received the intervention (full-risk Medicaid managed care) was determined by place of residence rather than random assignment. Time 1 data collection began in August 1997, 19 months after the mandatory HMO program began. Time 2 data were collected six months after the initial interview with each participant, with the final interviews taking place in early 1999.

The analyses were conducted with data collected from Medicaid recipients with serious mental illness who were recruited as outpatients at a Tidewater area community service board and a Richmond area community service board. Trained interviewers who had clinical experience with clients who have serious mental illness conducted initial structured research interviews with 243 outpatients—123 (51 percent) in the Tidewater area and 120 (49 percent) in the Richmond area.

Access to study subjects was through personnel of the community service boards, who generated a list of clients and asked those who were eligible to speak with a researcher about participating in a research interview. Research personnel then contacted those who agreed and explained the study in detail and obtained written informed consent. The consent form and other research procedures were approved by the Committee on the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Carolina at Chapel Hill.

As part of a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration initiative to examine managed behavioral health care in the public sector, the Tidewater managed care study used a survey instrument developed with investigators at other sites. The instrument covered several domains, including demographic information, quality of life, clinical history, health status, mental health symptoms, substance use, satisfaction, and service use.

We focused on service use, symptoms, and health status and created dichotomous variables for each. Information about service use was obtained by asking clients whether they had used specific mental health and substance abuse services in the previous three months. Physical and mental health status were measured with the physical component summary (PCS-12) and mental component summary (MCS-12), respectively, of the Medical Outcomes Study 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) (14). Severity of symptoms was measured with the global severity index of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (15).

Chi square tests and t tests were used to compare the two groups in demographic, social, clinical, and service use variables at time 1. The analyses then focused on two research questions. First, if symptom severity at time 1 is controlled for, how do the service use patterns of persons with serious mental illness compare between the full-risk and no-risk conditions? Second, if health status at time 1 and service use are controlled for, does the type of managed care arrangement affect health status six months later? The SAS statistical package was used for all analyses.

To address the first question, a list of key psychiatric and medical services was adapted from the recommendations of the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) (16). Chi square tests were used to compare the crude proportions of the two groups that reported use of each key service during the three months before the time 2 interview. Logistic regression was then used to estimate an adjusted odds ratio for each key psychiatric and medical service, controlling for symptom severity and physical health status at time 1.

The second question was addressed with use of regression models. Linear regression was used to predict scores on the SF-12 mental and physical component summaries at time 2. Backward stepwise selection was used, with a p value below .05 as the deletion criterion. The initial predictors in the models included the managed care condition, four dichotomous variables that indicated use of each key outpatient psychiatric service—case management, contact with a psychiatrist, counseling, and vocational training—and a dichotomous variable that indicated the use of any key medical service—primary care, specialty care, or admission—during the three months before the time 2 visit. The interaction of risk condition and case management was also included, because the nature of case management services may differ between sites. In each initial model, the time 1 score for the dependent variable was included as a covariate.

Results

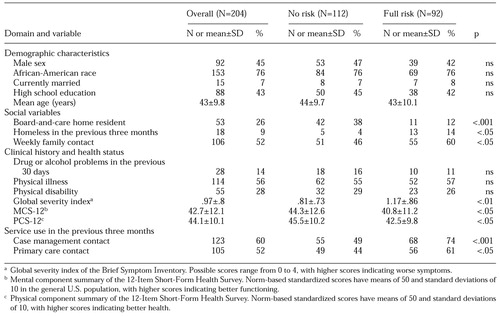

Participants in the full-risk and no-risk groups who completed both the time 1 and time 2 assessments were similar demographically, as can be seen from Table 1. At time 1, the no-risk group (Richmond area) had a higher proportion of board-and-care home residents, a lower proportion who reported homelessness in the previous three months, and a lower proportion reporting weekly family contact than the full-risk group (Tidewater area). The no-risk group also reported better mental health, as indicated by lower scores on the global severity index of the BSI, and less use of case management and primary care than the full-risk group. Clients in the no-risk group reported better mental and physical health status, as indicated by higher MCS-12 and PCS-12 scores, than clients in the full-risk group.

Six-month follow-up rates were 92 (75 percent) of 123 in the full-risk group and 112 (93 percent) of 120 in the no-risk group. In both groups, clients who were lost to follow-up had less housing stability, less disability, and fewer symptoms than those who were retained. In the full-risk group, clients who were lost to follow-up reported better mental health at time 1 than those who were retained.

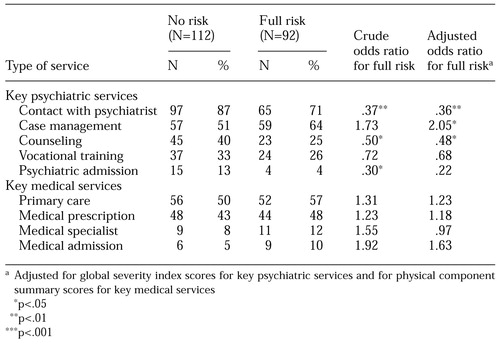

The crude and adjusted odds ratios for the full-risk group relative to the no-risk group for the three-month period preceding the time 2 interview are shown for each key psychiatric and medical service in Table 2. After adjustment for time 1 symptoms, clients in the full-risk group were more likely to have received case management but less likely to report contact with a psychiatrist or receipt of individual, group, or family counseling than clients in the no-risk group. The results for vocational training and psychiatric admission were not significant but suggested that clients in the full-risk group were less likely to have received these services. For key medical services, there was a nonsignificant pattern of more service use for clients in the full-risk group.

At time 2, clients in the full-risk group continued to report worse mental and physical health than clients in the no-risk group. Respective scores were 41.4 and 48.1 on the MCS-12 (t=4.15, df=190, p<.001) and 41.3 and 46.4 on the PCS-12 (t=3.30, df=190, p<.001). To control for the differences in health status at time 1, we included the time 1 scores for the dependent variables in the linear regression models.

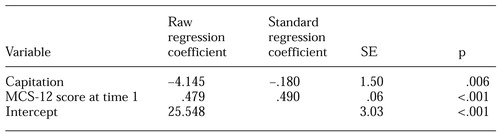

After backward stepwise regression, the only significant predictors in the final model of the MCS-12 score at time 2 were the score at time 1 and the managed care condition (Table 3). When MCS-12 score at time 1 was controlled for, the full-risk managed care condition was a predictor of poorer mental health. The difference of 4.1 points in the MCS-12 score that was associated with capitation in our model is of only modest clinical significance. In the study in which the validity of the SF-12 was established (14), people with serious mental and physical illness scored 9.3 points lower than people with serious physical illness alone, while people with mental illness alone scored 16.8 points lower than people with only a minor medical illness.

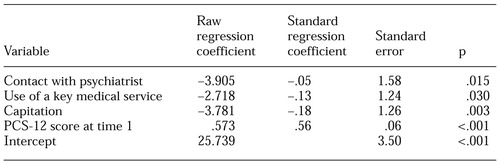

In the final linear regression model for the PCS-12 score at time 2, the managed care condition, contact with a psychiatrist in the previous three months, use of any physical health service in the previous three months, and PCS-12 score at time 1 were significant predictors, as shown in Table 4. Contact with a psychiatrist and the use of any physical health service were associated with poorer physical health status. The full-risk managed care condition was associated with poorer physical health status. Again, the 3.9-point difference in PCS-12 score that was associated with capitation in our model is of moderate clinical significance. In the study in which the validity of the SF-12 was established, people with serious mental and physical illness scored 2.4 points lower than people with serious physical illness alone, while people with mental illness alone scored 1.9 points higher than people with only a minor medical illness (14).

Discussion and conclusions

We found differences between the service use patterns of persons with serious mental illness in a full-risk Medicaid HMO and those in a no-risk Medicaid plan. Services covered by a capitated fee, including outpatient services provided by a psychiatrist and individual, group, and family counseling, were used significantly less by the enrollees in the full-risk HMO than by those in the no-risk Medicaid program. Use of inpatient services, also covered by a capitated fee, showed a similar trend. Case management, a service paid for through separate funds on a fee-for-service basis under both arrangements, was more commonly reported by clients in the full-risk group than by those in the no-risk group.

These patterns of service use suggest that the financial incentives associated with the full-risk arrangement had an impact in the expected direction. The community service board in the full-risk setting had a strong incentive to use case management, because doing so provided income in addition to the capitated payment received from the behavioral health MCO. The incentive to provide case management and bill for it was less strong in the no-risk setting, because all services could be billed on a fee-for-service basis.

The full-risk managed care model we studied in the Tidewater region had unique characteristics. Although the state Medicaid agency paid HMOs a single capitated fee to cover both mental and physical health services, the HMO in this study provided mental health services through a capitated subcontract with a subsidiary behavioral health MCO. By contracting with the existing public mental health centers to provide outpatient services, the behavioral health MCO ensured that persons with serious mental illness had access to providers who had appropriate experience. By allowing these mental health centers to continue to bill for case management outside the capitated contract, the state Medicaid agency limited some of the financial risk of the community service boards.

At time 1, study participants in the full-risk group reported poorer mental and physical health than participants in the no-risk group. Possible explanations for the differences at time 1 include sampling bias—that is, nonrepresentativeness of the samples—and real population differences. Because staff of the community service boards approached every eligible client who could be located, the clients enrolled in this study can be considered a representative sample of all community service board clients who have severe mental illness. Other possible reasons for these differences are that the community service boards and HMOs targeted services for sicker clients in the full-risk setting or that the program resulted in poorer outcomes that were already apparent at the time of the time 1 interviews. Future research may be able to avoid the time 1 differences by focusing on new Medicaid enrollees.

We found that adults with severe mental illness in the full-risk managed care setting had poorer outcomes, consistent with our hypotheses. When scores at time 1 were controlled for, the full-risk condition was associated with poorer mental and physical health at time 2.

The results of this study support earlier findings that the service use patterns of adults with severe mental illness are affected by risk-based managed care contracts. Previous studies have not shown a consistent effect of service use patterns on client outcomes under capitation (10,11,12). Because ours was a quasi-experimental study, we cannot draw definite conclusions. We found that the full-risk managed care model we studied may have had an adverse effect on the mental and physical health of persons with serious mental illness.

Virginia's mandatory HMO program, although limited in geographic scope, saved the state Medicaid agency at least $16 million during its first two years of operation (17). The program expanded to the Richmond area in 1999, providing indirect evidence that the program is acceptable for MCOs and the state Medicaid agency. Whether this is sound public policy can be determined only by continued evaluation and public debate.

Although this observational study provided no definitive evidence on capitated mental health services for adults with serious mental illness, it did provide evidence that full-risk capitation for this population may have adverse consequences. Although the clinical effects of capitation in our study were modest, they were found over a relatively short period. Six months is not a long follow-up period for persons who have serious mental illness. However, our findings parallel those from Utah, where adverse effects became apparent only after about three years of follow-up (12).

Longer-term follow-up studies would help determine whether the negative effects we found in Virginia persist or intensify. In the absence of longer-term data, caution in the use of risk-based contracts for services for persons with serious mental illness is warranted.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by cooperative agreement UR-7-TI11272 with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Dr. Morrissey, Dr. Stroup, and Mr. Ellis are affiliated with the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 275 Airport Road, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7590 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Merwin is with the Southeastern Rural Mental Health Research Center of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of clients with serious mental illness under no-risk and full-risk managed care arrangements at time 1

|

Table 2. Service use by clients with serious mental illness under no-risk and full-risk managed care arrangements during the three months before six-month follow-up

|

Table 3. Final linear regression model predicting mental component summary (MCS-12) score at time 2

|

Table 4. Final linear regression model predicting physical component summary (PCS-12) score at time 2

1. Durham M: Mental health and managed care. Annual Review of Public Health 19:493-505, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hoge MA, Davidson L, Griffith EEH, et al: Defining managed care in public-sector psychiatry. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1085-1089, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Christianson JB, Manning W, Lurie N, et al: Utah's prepaid mental health plan: the first year. Health Affairs 14(3):160-172, 1995Google Scholar

4. Callahan JJ, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH, et al: Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Affairs 14(3):173-184, 1995Google Scholar

5. Dickey B, Normand SL, Norton EC, et al: Managing the care of schizophrenia: lessons from a 4-year Massachusetts Medicaid study. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:945-952, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Stroup TS, Dorwart RA: The impact of a managed mental health program on Medicaid recipients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:885-889, 1995Link, Google Scholar

7. McFarland BH, Johnson RE, Hornbrook MC: Enrollment duration, service use, and costs of care for severely mentally ill members of a health maintenance organization. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:938-944, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Popkin MK, Lurie N, Manning W, et al: Changes in the process of care for Medicaid patients with schizophrenia in Utah's prepaid mental health plan. Psychiatric Services 515-523, 1998Google Scholar

9. Liu CF, Manning WG, Christianson JB, et al: Patterns of outpatient use of mental health services for Medicaid beneficiaries under a prepaid mental health carve-out. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 26:401-415, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Warner R, Huxley P: Outcomes for people with schizophrenia before and after Medicaid capitation at a community agency in Colorado. Psychiatric Services 49:802-807, 1998Link, Google Scholar

11. Lurie N, Moscovice IS, Finch M, et al: Does capitation affect the health of the chronically mentally ill? Results from a randomized trial. JAMA 267:3300-3304, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Manning WG, Liu CF, Stoner TJ, et al: Outcomes for Medicaid beneficiaries with schizophrenia under a prepaid mental health carve-out. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 26:442-450, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Fried BJ, Topping S, Morrissey JP, et al: Comparing provider perceptions of access and utilization management in full-risk and no-risk Medicaid programs for adults with a serious mental illness. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research 27:29-46, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12): construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 32:220-233, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Derogatis LR: A Brief Form of the SCL-90-R: A Self-Report Symptom Inventory Designed to Measure Psychological Stress: Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI). Minneapolis, National Computer Systems, 1993Google Scholar

16. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Virginia Division of Medical Assistance Services: Managed Care Program Summary. Richmond, 2000. Available at www.cns.state.va.us/dmas/managed_care/manged_care.htmGoogle Scholar