Rehab Rounds: Improving Medication Compliance of a Patient With Schizophrenia Through Collaborative Behavioral Therapy

Abstract

Introduction by the column editors: Numerous factors influence a patient's decision to accept or reject prescribed medications, including the patient's personal values, environmental conditions, and the quality of the patient-physician relationship (1). Guidelines for evaluating and managing noncompliance with medication regimens by patients with schizophrenia take this multidimensional perspective into account, emphasizing functional assessment of nonadherence behaviors and individualized behavior-change strategies to secure and maintain the patient's cooperation (2). Moreover, a collaborative approach to planning pharmacotherapy is required to ensure medication compliance, with a particular emphasis on linking the positive effects of medications with the patient's personal goals and desires for better functioning and quality of life (3).The following case study illustrates the application of principles for enhancing medication compliance in the treatment of a woman diagnosed as having schizophrenia, paranoid type. Strategies presented by Dr. Heinssen include collaborative treatment contracts, analysis of adherence behaviors, and techniques for boosting medication cues and reinforcers in the patient's home. The therapy described was provided in the Life Skills partial hospitalization and psychiatric rehabilitation program, a multidisciplinary, multilevel outpatient service of the now-closed Chestnut Lodge Hospital in Rockville, Maryland. The program integrated medical, social-learning, and cognitive-behavioral interventions for psychosis within a psychiatric rehabilitation framework.

Ms. J, a Caucasian woman in her mid-thirties, entered the Life Skills partial hospitalization program of Chestnut Lodge Hospital in 1998, after her acute psychotic symptoms had been stabilized in inpatient treatment. Events leading to Ms. J's index hospitalization had been repeated many times during her 15-year struggle with serious mental illness: soon after she discontinued neuroleptic therapy, she experienced anxiety, paranoia, and auditory hallucinations, followed by social withdrawal, deterioration of self-care, and, eventually, rehospitalization.

The reasons Ms. J gave for stopping her medications included side effects such as constipation and amenorrhea, a belief that "I should be able to make it on my own," and difficulty remembering dosing times. During her most recent inpatient admission, her previous medication—risperidone, 4 mg at bedtime—was started again, and her positive symptoms improved significantly. However, her lingering reservations about prophylactic pharmacotherapy threatened her commitment to long-term medication compliance.

Collaborative treatment planning

Suspiciousness, skepticism, and low motivation for therapy were obstacles to Ms. J's participation in outpatient treatment. To try to establish a positive alliance and to boost Ms. J's interest in rehabilitative activities, the social work case manager in the partial hospitalization program helped her elaborate long-term goals whose achievement had been interrupted by her illness. These discussions, which took place during the first two weeks of partial hospitalization, represented the first step in developing a collaborative treatment contract related to the purpose and form of outpatient therapy (4).

The case manager used techniques of empathic reflection, clarification, and elaboration of personal goals to help Ms. J define her overall objectives and to identify the steps necessary for achieving these goals. For Ms. J, acquiring greater autonomy was paramount, as her economic reliance on her aging parents troubled her. She declared her ambition to become a sales clerk in a women's clothing store and to earn enough money to purchase groceries independently. Ms. J acknowledged that to accomplish these goals she had to stay out of the hospital, find a suitable part-time job, and act "normally" in the workplace.

Ms. J identified auditory hallucinations, paranoid fears, and feelings of panic as potential barriers to employment. She admitted that medications had alleviated these symptoms in the past and concluded that medication adherence would be worth the effort "if taking the meds could help me keep a job."

Equipped with a better rationale, Ms. J showed greater interest in maintaining adherence over time. She agreed to a rehabilitation plan that targeted, in sequence, reliable self-administration of medications; adjunctive symptom-management techniques such as applied relaxation, self-instructional training, and cognitive restructuring; workplace social skills; and successful vocational placement.

With Ms. J's consent and involvement, medication management training began with a functional analysis of the barriers to and supports for medication adherence that were present in her apartment, including Ms. J's own behaviors. On the basis of interview data, direct observation, and input from knowledgeable informants, functional analysis pinpoints a person's strengths and weaknesses in performing target behaviors, as well as environmental events that influence responses (5). Several home visits by the case manager established that Ms. J's medication habits were poorly developed, were compounded by memory impairments, and were not supported by environmental cues or contingencies for reliable self-administration.

For example, medication bottles were strewn haphazardly about Ms. J's apartment or remained unopened in her purse. Although Ms. J claimed that she took medications "sometime after dinner," she had not established a consistent time to take them. She admitted that she often forgot to take her medications before she fell asleep, became flustered when she realized her error, and could not remember her doctor's instructions about missed doses. Finally, her apartment lacked any external signals, reminders, or rewards for reliable medication self-administration, a situation that magnified the impact of her functional neurocognitive deficits.

An environmental approach

On the basis of these observations, environmental interventions were proposed to offset Ms. J's memory problems and to reinforce adaptive medication behaviors. During the first two months of Ms. J's partial hospitalization treatment, features of her apartment were reorganized to make self-administration procedures routine, to establish conspicuous medication reminders, and to provide contingent social reinforcement for adherence.

Environmental engineering began by simplifying medication storage and disbursement procedures. The case manager arranged weekly sessions with a psychiatric nurse, who taught Ms. J to transfer medications from bottles to a compartmentalized storage box and then to take the pills according to labeled instructions. Next, the case manager helped Ms. J analyze her evening routine, with the goal of finding a consistent daily activity to anchor medication self-administration.

Ms. J reported that she never missed the televised evening news, which served as her primary link to the outside world. She agreed to take her medications at the start of the program, using the opening music as a cue for the evening doses. The case manager suggested that Ms. J store the medication box next to her television set to strengthen the link between the news program and taking the medication. Ms. J agreed and proposed that she place a sign above the television as an additional cue.

Ms. J, her parents, and the case manager met during the third week of treatment to review the proposed rehabilitation plan. Ms. J's father, delighted by his daughter's maturity and cooperation, offered to call each evening after the news to check on her medication status. Ms. J readily agreed, especially when her father offered to extend the telephone conversation by several minutes whenever she had taken her medication before he called.

Ms. J also accepted the suggestion that she seek feedback from peers during weekly meetings of her therapeutic contracting group. During those sessions, led by a rehabilitation counselor, patients systematically set treatment goals, reviewed their progress, and updated individualized behavior-change programs (6).

With the addition of these social reinforcers, Ms. J's medication regimen was complete. Through active involvement in treatment planning, Ms. J had established a set time, a set place, and a dependable reinforcement system to support her efforts toward medication self-reliance.

Evaluating the interventions

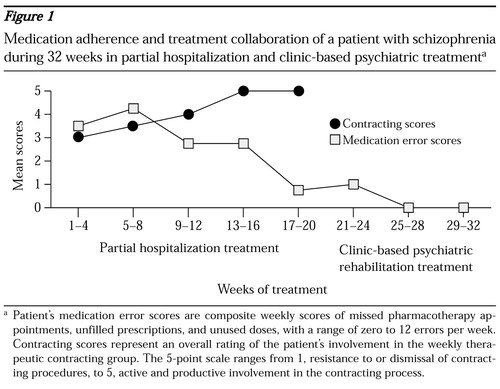

Figure 1 depicts Ms. J's response to medication adherence interventions during partial hospitalization (weeks 1 through 20) and after discharge to the affiliated clinic-based psychiatric rehabilitation program (weeks 21 through 32). Medication adherence was quantified by the psychiatric nurse, who recorded medication errors for each week during the weekly instructional sessions. Missed pharmacotherapy appointments (up to one per week) were scored 3 points; unfilled prescriptions (up to one per week), 2 points; and unused doses (up to seven per week), 1 point each. The range was thus zero to 12 error points a week.

Ms. J made medication errors often during the first eight weeks of partial hospitalization (mean±SD error score, 3.9±1.9 per week), but the number of errors fell dramatically during the third month of therapy (mean±SD error score, 2.8±1.6 per week). This result can be attributed to the cumulative effect of rehabilitation interventions introduced during the first two months, as no other changes had occurred in Ms. J's medical, social, or psychological circumstances. Medication errors remained constant during month 4 (mean±SD error score, 2.8± 1.5 per week), despite significant stress brought on by the sale of Ms. J's apartment building.

When the sale of her building forced Ms. J to move, she worked closely with her case manager to choose and relocate to a new and appropriate domicile—another apartment in the community—and to transfer medication cues and reinforcers there. At the same time, Ms. J's parents supported her efforts to maintain independent housing, and during the therapeutic contracting sessions her peers praised her businesslike demeanor. These social supports within and outside the treatment program bolstered Ms. J's commitment to the master treatment plan and helped produce further improvements in medication adherence in subsequent weeks.

The system of environmental cues remained constant throughout the first eight months of treatment, but social reinforcement changed in week 21. Ms. J's evening conversations with her father were gradually decreased as she took her medications more reliably. Her father was so pleased with her progress that he offered to exchange daily phone conversations (continuous reinforcement) for weekend shopping trips (intermittent reinforcement). Ms. J agreed to this trade and noted that she felt like less of a burden on her parents since she was taking better care of herself.

Figure 1 also shows Ms. J's contracting scores during weeks 1 to 20 of partial hospitalization, when the weekly contracting group ended. Contracting scores were determined by rehabilitation counselors at the weekly contracting sessions, using a scale of 1 to 5. Scale anchors were 1, resistance to or dismissal of contracting procedures (problem solving, goal setting, and contract revision activities); 3, passive acceptance of contracting interventions; and 5, active and productive involvement in the therapeutic contracting process.

Ms. J's involvement in therapeutic contracting increased consistently over time; her score increased from 3 to 5, suggesting a gradual blossoming of the rehabilitation alliance. Although she was only modestly engaged in collaborative treatment planning at the start of partial hospitalization, she became highly invested in the weekly ritual of setting goals, reviewing progress, and updating interventions. It is noteworthy that her motivation for therapy—as reflected in her contracting scores—increased before her medication adherence improved, and it progressed independently of further changes in adherence to pharmacotherapy.

Ms. J achieved her aim of reliable self-administration of medication after six months of outpatient treatment, registering perfect adherence over the ensuing two months. With that goal accomplished, the focus of rehabilitation shifted toward developing stress management skills and social competencies for the workplace. Using these techniques, Ms. J acquired a paid position in a sheltered workshop nine months later, and this work served as a stepping-stone to competitive community employment, which she attained in treatment month 24. Four years after partial hospitalization therapy began, Ms. J remains out of the hospital, working part-time and adhering to pharmacotherapy.

Afterword by the column editors: Ms. J's treatment in the Life Skills program illustrates the complex interplay of illness features, personal values, interpersonal supports, and environmental conditions in determining a patient's adherence to medication regimens. This case study highlights the value of collaborative treatment planning to deliver rehabilitation services that are individualized to a person's circumstances and tailored to his or her natural milieu. For example, Ms. J's attention, memory, and problem-solving difficulties were overcome by introducing control stimuli, behavioral routines, and social reinforcers into her apartment, thereby creating a pathway for adaptive behavior (7).

The use of such behaviorally oriented environmental engineering was the subject of a previous Rehab Rounds column (8), and it has been validated in a randomized controlled study (9). In Ms. J's case, the program's use of basic behavioral principles combined with the staff's willingness to address Ms. J as a partner ensured the long-term success of the treatment program, from medication-adherence training to job placement in the community.

Dr. Heinssen is chief of the Psychotic Disorders Research Program of the Division of Mental Disorders, Behavioral Research, and AIDS of the National Institute of Mental Health, 6001 Executive Boulevard (MSC 9615), Bethesda, Maryland 20892 (e-mail, [email protected]). Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., and Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., are editors of this column.

Figure 1. Medication adherence and treatment collaboration of a patient with schizophrenia during 32 weeks in partial hospitalization and clinic-based psychiatric treatmenta

a Patient's medication error scores are composite weekly scores of missed pharmacotherapy appointments, unfilled prescriptions, and unused doses, with a range of zero to 12 errors per weekContracting scores represent an overall rating of the patient's involvement in the weekly therapeutic contracting group. The 5-point scale ranges from 1, resistance to or dismissal of contracting procedures, to 5, active and productive involvement in the contracting process.

1. Corrigan PW, Liberman RP, Engel JD: From noncompliance to collaboration in the treatment of schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1203-1211, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Fenton WS, Blyler CR, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:637-651, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Noordsy DL, Torrey WC, Mead S, et al: Recovery-oriented psychopharmacology: redefining the goals of antipsychotic treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61(suppl 3):22-29, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

4. Heinssen RK, Levendusky PG, Hunter RH: Client as colleague: therapeutic contracting with the seriously mentally ill. American Psychologist 50:522-532, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Haynes SN, O'Brien WH: Functional analysis in behavior therapy. Clinical Psychology Review 10:649-668, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Heinssen RK, Hunter RH: Therapeutic contracting: an effective strategy for competency-based treatment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Skills 2:128-148, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Heinssen RK: The cognitive exoskeleton: environmental interventions in cognitive rehabilitation, in Cognitive Rehabilitation for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Edited by Corrigan PW, Yudofsky SC. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1996Google Scholar

8. Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC: Two case studies of cognitive adaptation training for outpatients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 51:25-29, 2000Link, Google Scholar

9. Velligan DI, Bow-Thomas CC, Huntzinger CD, et al: A randomized controlled trial of the use of compensatory strategies in schizophrenic outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1317-1323, 2000Link, Google Scholar