The Effect of Intensive Case Management on the Relatives of Patients With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Relatives play a vital role in caring for patients with severe mental illness but receive inadequate support from psychiatric services. Evidence suggests that although intensive case management is directed primarily at patients, relatives may benefit as well. This study examined whether relatives of patients who were receiving intensive case management had more contact with mental health professionals than relatives of patients who were receiving standard case management. It also examined whether relatives of patients receiving intensive case management appraised caregiving less negatively and experienced less psychological distress than relatives of patients receiving standard case management. METHODS: The sample was drawn from the pool of patients participating in the UK700 randomized controlled trial of intensive case management. Prospective data on contact between case managers and the relatives of 146 patients were collected over a two-year period. At a two-year follow-up assessment, relatives of 116 patients were interviewed with the Experience of Caregiving Inventory and the 12-item General Health Questionnaire. RESULTS: Considerably more relatives of patients receiving intensive case management had contact with a case manager during the study period than relatives of patients receiving standard case management (70 percent compared with 45 percent). However, relatives of patients receiving intensive case management did not appraise caregiving less negatively or experience less psychological distress than relatives of patients who were receiving standard case management. CONCLUSIONS: Reducing case managers' caseloads alone will not guarantee adequate support for relatives. Instead, providing more support will need to be an explicit aim, and staff will require specific additional training to achieve it.

Interest in the effects of patients' treatment on relatives began in the 1960s when Grad and Sainsbury (1,2) evaluated a new community-based psychiatric service. In the decades that followed, concerns that deinstitutionalization would place an unacceptable burden on relatives were not realized. Indeed, findings indicated that relatives benefited when patients were offered community alternatives to hospital treatment (3,4,5).

With community treatment now established as standard care, attention has turned to the effects of different types of such treatment on relatives and to whether services that target primarily patients also benefit relatives. The latter possibility is of particular interest given that interventions aimed specifically at providing support for relatives—namely, psychoeducation and counseling—are rarely offered routinely and have limited efficacy (6,7). A recent meta-analysis (8) concluded that both assertive community treatment and clinical case management are more effective than usual treatment in the domains of family burden and family satisfaction with services.

However, findings about the effectiveness of intensive case management are less consistent. Although some studies have demonstrated that relatives of patients receiving intensive case management experience less burden than relatives of patients receiving standard care (9,10), the PRiSM Psychosis Study (11) found that a routine and long-established intensive community service did not influence relatives' caregiving activities or psychological distress. However, methodological differences between studies make comparison difficult. Moreover, although consensus holds that family support is an important component of care for patients with severe mental illness (12), little is known about case managers' routine contact with relatives and how intensive case management compares with standard care. Without these data it is unclear whether the lack of evidence for an effect of intensive case management on relatives' experience is due to there being little or no difference between standard and intensive case management in how relatives are involved.

We aimed to investigate the effect of intensive case management on relatives while taking into consideration their contact with case managers. Our sample was drawn from the UK700 randomized controlled trial, in which caseload size differed between the experimental and control services but all other potentially influential variables, such as access to other services and training offered to case managers, were the same (13). Supporting relatives was not an explicit aim of the intensive case management service. However, it was thought that smaller caseloads might enable case managers to have more contact with relatives, which might in turn allow problems frequently cited by relatives to be addressed, particularly exclusion from the treatment process and a lack of information about the patient's illness and treatment (14).

Methods

Recruitment

The study participants were the relatives of patients who had been recruited for the UK700 Trial, which has been described in detail elsewhere (15). The patients were 18 to 65 years of age, had a diagnosis of psychosis according to the Research Diagnostic Criteria (16) and established by a structured examination of case notes (17), and had a minimum of two previous psychiatric hospital admissions, one of which was in the two years preceding enrollment in the study. Patients were excluded if they had organic brain damage or a primary diagnosis of substance abuse.

Patients were identified through a systematic review of community mental health team caseloads. Patients' informed consent to participate was obtained, and baseline assessments were made. After this assessment, the patients were randomly assigned to two years of either standard case management, in which case managers had caseloads of 30 to 35 patients, or intensive case management, in which case managers had caseloads of 10 to 15 patients. The patients were reassessed at the end of the two-year period. At each assessment, they were asked whether they had had face-to-face contact with a relative at least twice a week and, if so, whether they consented to a researcher's approaching their relative. Relatives' consent to be interviewed was then sought. The relatives were typically interviewed within one month after the patient's interview. Each center obtained local ethics committee approval for the study. Data were collected between February 1994 and April 1996.

Case managers' contact with relatives

During the study period, all members of the mental health teams—community psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists, social workers, psychologists, and psychiatrists—recorded their activities with or on behalf of study patients. These process data have been described in full elsewhere (18). The focus of this study was their contact with patients' relatives. Contacts with relatives, both face-to-face and by telephone, were recorded if they lasted more than 15 minutes. Two types of contact were distinguished: all case manager contacts with relatives irrespective of the focus, and a subset of these in which the contact was focused primarily on the relative. The kinds of activity such contacts included were providing advice or education about the patient's illness, providing support, helping with problem solving, gathering information, and performing tasks related to child protection.

The sample was restricted to patients who had frequent contact with a relative at both baseline and follow-up, because it was presumed that case managers could not be expected to have contact with a patient's relative if the patient did not. Overall, 203 patients had an eligible relative at both time points. Standard case managers at one site did not collect data on case manager contacts with relatives, so all 57 patients from that site, in both standard and intensive case management, were excluded from the analyses. The excluded patients did not differ from those who were included, except that a smaller proportion were from ethnic minority groups (35 percent compared with 51 percent; χ2=6.43, p=.04). Thus, data on case manager contacts with relatives were available for 69 patients receiving standard case management and 77 patients receiving intensive case management, giving a response rate of 72 percent. We could not determine from the data collected how many relatives each patient had frequent contact with during the study period. When interpreting the results, we adopted the most prudent approach and assumed that each patient had frequent contact with only one relative.

Relatives' experience

Outcome data were collected from relatives at baseline and at the two-year follow-up assessment. A stress-appraisal-coping paradigm was used to conceptualize relatives' experience (19). Measures of burden were therefore rejected in favor of instruments that would assess components of this paradigm—namely, the Experience of Caregiving Inventory (ECI) (19), which measures appraisal of caregiving, and the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) (20), which measures psychological distress.

The ECI is a 66-item self-report questionnaire developed for use with relatives of patients with mental illness. Using a 5-point scale anchored at "never" and "always or nearly always," relatives rate the frequency with which they have thought about each item during the preceding four weeks. The ECI is divided into a negative appraisal scale (52 items) and a positive appraisal scale (14 items). It can be further divided into ten subscales, one of which—problems with services (eight items)—was examined in this study. The problems with services subscale ranges from 0 to 32, with a higher score indicating more negative appraisal of services.

The GHQ-12 is a widely used self-report questionnaire. Using a 4-point scale, relatives rate the frequency with which they have experienced 12 indicators of psychological distress during the preceding four weeks. Internal and test-retest reliability and validity coefficients (specificity and sensitivity) for this instrument are satisfactory (21). As recommended (21), we used the straightforward GHQ (SGHQ) score. Because this method of scoring has been criticized for its lack of sensitivity to feelings of resignation, an alternative scoring method was also used in which "same as usual" on negative items indicates the presence of distress, producing a chronic GHQ (CGHQ) score (22). To determine potential psychiatric caseness, we used cutoffs of 4 or more on the SGHQ and 5 or more on the CGHQ (23). Scores on both the SGHQ and the CGHQ range from 0 to 12, with a higher score indicating greater psychological distress.

For several reasons, primarily ineligibility or a refusal to provide consent, some relatives who were interviewed at baseline were not reinterviewed at follow-up. However, because patients had been randomly allocated to treatment groups, comparisons could be made on the basis of follow-up data alone. To ensure that randomization had been successful, relatives' baseline experiences were compared; no significant effect of treatment group was found. An interview with a relative was completed for 116 of the 251 UK700 Trial patients who had an eligible relative at follow-up (48 patients receiving standard case management and 68 receiving intensive case management). This response rate of 46 percent, although low, is similar to that of other studies (24,25).

Methodological limitations

Because outcome and process data were collected separately, we encountered two problems during the study. First, case managers were asked to record their contacts with "carers," who potentially included friends, neighbors, and relatives, whereas outcome data were collected only from relatives. However, this discrepancy probably had only a minimal effect, because in practice almost all carers were patients' relatives. Second, because the case managers did not record details of the relative with whom they had contact, process data could not be directly related to the relatives' experience.

Statistical methods

Comparisons by treatment group were made with the Mann-Whitney U test and chi square tests. All tests were two-tailed.

Results

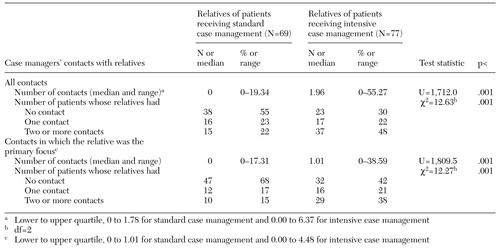

Case managers' contact with relatives

As Table 1 shows, relatives of patients receiving intensive case management had significantly more contact with case managers during the two-year study period than did relatives of patients receiving standard case management. This finding was observed for all contacts and for contacts focused primarily on the relative. More than 70 percent of the relatives of patients receiving intensive case management had some contact with a case manager, and 58 percent were the primary focus of a contact. By contrast, 45 percent of the relatives of patients receiving standard case management had some contact with a case manager, and 32 percent were the primary focus of a contact. More than twice as many relatives of patients receiving intensive case management as relatives of patients receiving standard case management were the subject of two or more contacts with case managers.

Relatives' experience

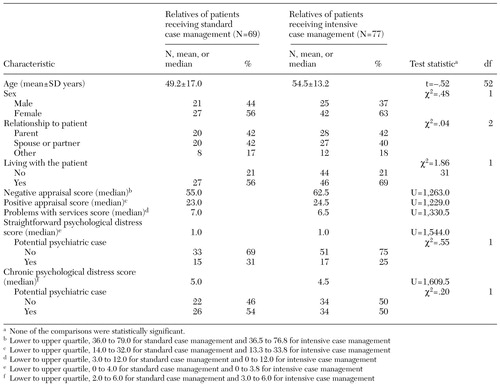

As Table 2 shows, no significant sociodemographic differences were found between the two groups. The relatives' mean±SD age at the two-year follow-up assessment was 52±15 years, and 60 percent were women. Two-fifths (42 percent) of the relatives were the patient's parent, and a similar proportion (41 percent) were the patient's spouse or partner. Nearly two-thirds (63 percent) of the relatives lived with the patient.

No significant differences were observed in relatives' appraisal, either positive or negative. Relatives of patients receiving intensive case management did not appraise problems with services less negatively than relatives of patients receiving standard case management. Just over a quarter of the relatives (28 percent) were identified by SGHQ scores as potential psychiatric cases. This proportion exceeded one-half (52 percent) when feelings of resignation were taken into account. However, no between-group differences in relatives' psychological distress were observed either before or after feelings of resignation were taken into account.

Additional analyses were conducted to determine whether the lack of between-group differences in outcome could be explained by a lack of difference in case manager contacts for the subgroup of relatives from both groups who were interviewed at follow-up. Of the 116 relatives for whom outcome data were available, process data were available for 71, of which 32 were relatives of patients receiving standard case management and 39 were relatives of patients receiving intensive case management. The median number of contacts these relatives had with case managers during the two-year study period was 1.05 [interquartile range (IQR)=3.01] and 2.76 (IQR=7.30), respectively (Mann-Whitney U=480.50, p=.09). When contacts that were focused on the relative were examined, the relatives of patients receiving standard case management had a median of zero contacts (IQR=2.00), whereas relatives of patients receiving intensive case management had a median of two contacts (IQR=6.00) (U=424.50, p=.02).

Although these between-group differences were less marked than those of the larger group, they suggest that the lack of difference in experience among relatives of patients receiving standard or intensive case management is not explained by a lack of difference in their contacts with case managers.

To assist with interpretation we also examined the effect of intensive case management on the clinical characteristics of the subgroup of 116 patients whose relative was included in the outcome study. Consistent with the main results of the UK700 Trial (15), no significant treatment group differences were found in patients' psychiatric hospital use, psychopathology, severity of symptoms, course of illness, or social functioning.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that case managers had significantly more contact with relatives of patients receiving intensive case management than with relatives of patients receiving standard case management, even though more contact with relatives was not a specific aim of the intensive case management service. Compared with relatives of patients receiving standard case management, fewer relatives of patients receiving intensive case management had no contact with a case manager and more than twice as many were the focus of several contacts. Thus it appears that a reduction in caseload size enables case managers not only to have contact with a greater proportion of relatives but also to have more contact with individual relatives. Nevertheless, despite the association between intensive case management and greater contact with relatives, the relatives' experience did not differ significantly from that of relatives of patients receiving standard case management. Three possible explanations for this result are discussed.

First, intensive case management may have had no impact on patient outcomes because the routine service to which it was compared was of high quality, incorporating several elements of assertive community treatment, including well coordinated services and in-community treatment (15). Because the severity of patients' symptoms is the strongest predictor of relatives' distress (26), the lack of impact of intensive case management on patients' outcomes means that differences in relatives' experience are unlikely. This interpretation is consistent with findings from two other studies of the effect of intensive case management on relatives (9,10), in which improvements in relatives' burden corresponded with improvements in patients' outcomes. However, because neither study reported the amount of support relatives received, it is impossible to determine whether differences in their experience were due to improvements in patients' outcomes or to greater support for relatives.

Alternatively, intensive case management may have failed to have an impact on relatives' experience because, despite its association with more case manager contact, it did not meet relatives' needs. Intensive case management clearly provides an opportunity for more family support, but the case managers who participated in this study received no explicit guidance in this area. Training case managers to use successful interventions, such as individualized family education approaches (27), may allow this opportunity to be developed.

Finally, it may be that relatives' experience did not differ between the two types of case management because the contacts that relatives of patients receiving intensive case management had with case managers were too infrequent for adequate support to be provided. The UK Government has recommended that relatives caring for a person with severe mental illness have their own caring, physical, and mental health needs assessed at least annually and also receive their own care plan to be implemented in discussion with them (28). These findings show that the target of annual contact is being achieved for only 15 percent of relatives routinely and for 38 percent of relatives of patients receiving intensive case management. Moreover, these figures may overestimate the actual proportions, because the study assumed that each patient had only one relative. Case managers' contacts with a patient's relative may in fact have been divided among several relatives.

It is important to understand why the amount of contact between case managers and relatives of patients receiving intensive case management is so low, particularly because the opportunity for a broader spectrum of clinical practice, including more work with families, is voiced by many staff members as a reason for joining the intensive case management teams. It may be that, because of the study design, the data did not include a substantial number of incidental contacts with relatives that occurred when case managers visited a patient who lived under the same roof as the relative. We have no way of quantifying these incidental contacts or of establishing whether they were more or less likely in the intensive case management service. However, even if these brief, incidental contacts are numerous, it is unlikely that the support that relatives require can be provided without some longer contacts focused on their needs.

Beyond methodological considerations, the amount of contact may have been low because intensive case managers considered support for relatives to be outside of their duties. Although providing support, advice, and services to relatives inevitably diverts scarce resources from patients, it is considered an important component of patient care (12) and one of the best ways of helping patients (28). However, which professionals should provide family support and whether it is the responsibility of the professionals caring for the patient remains unclear. If future research establishes that frequent contact with relatives is indeed beneficial, this study has shown that such contact will need to be an explicit aim if it is to be achieved.

An alternative reason for intensive case managers' low levels of contact with relatives stems from the challenges arising from working with families. Explaining to families the nature of psychotic illnesses, how treatments work, and—most difficult of all—how an individual's prognosis can be expressed in the short, the medium, and the long term is difficult. Also, bridging the gap between patient confidentiality and relatives' need for information can be problematic (29), although strategies for overcoming this issue are available (30). It cannot be assumed that staff already have the necessary skills and confidence to support relatives. Despite striking improvements in the range and quality of information contained in booklets and videos, these are inevitably general, whereas the questions relatives ask are often specific and difficult to answer. Specific training for staff will be necessary if higher levels of family contact and support are to be achieved.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that in current clinical practice, contact between mental health professionals and patients' relatives is minimal. It also indicated that reducing caseloads will not, by itself, result in adequate contact, even when this reduction represents an effective doubling of the mental health workforce. Further research is required to establish whether relatives' psychological distress can be alleviated through greater contact with mental health professionals whose primary concern is the patient, or whether interventions specifically aimed at supporting relatives are required.

Acknowledgments

The sample for this study was drawn from the UK700 Trial, a collaborative study involving four clinical centers and funded by grants from the UK Department of Health and the National Health Service Research and Development Programme. The authors thank Tom Butler, Ph.D., Francis Creed, F.R.C.Psych., Janelle Fraser, B.A., Nick Tarrier, Ph.D., and Theresa Tattan, Ph.D. (Manchester); Catherine Gilvarry, B.Sc., Kwame McKenzie, M.R.C.Psych., Robin Murray, D.Sc., Jim van Os, Ph.D., and Elizabeth Walsh, M.R.C.Psych. (King's School of Medicine and Maudsley Hospital, London); John Green, Ph.D., Anna Higgitt, M.R.C.Psych, Elizabeth van Horn, M.R.C.Psych, Donal Leddy, B.A., and Peter Tyrer, F.R.C.Psych (St. Mary's and St. Charles', London); Rob Bale, M.R.C. Psych., Andy Kent, M.D., and Chiara Samele, Ph.D. (St. George's Hospital, London); Sarah Byford, M.Sc., and David Torgerson, Ph.D. (Center for Health Economics, York); and Simon Thompson, D.Sc., and Ian White, Ph.D. (Statistical Centre, London).

At the time of writing, Dr. Harvey was with the department of general practice and primary care at Guy's, King's and St. Thomas' School of Medicine in London, United Kingdom. Professor Burns and Dr. Fiander are with the department of community psychiatry at St. George's Hospital Medical School in London. Professor Huxley is with the health services research department of the Institute of Psychiatry in London. Ms. Manley is with the department of public mental health at the Imperial College School of Medicine in London. Professor Fahy is at the Maudsley Hospital in London. Send correspondence to Dr. Harvey at the Department of Psychology, The University of Reading, Earley Gate, Whiteknights Road, Reading, Berkshire RG6 2AL, United Kingdom (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Case managers' contacts with relatives during the two-year study period

|

Table 2. Characteristics at two-year follow-up of relatives of patients receiving standard or intensive case management

1. Grad J, Sainsbury P: Mental illness and the family. Lancet 9:544-547, 1963Crossref, Google Scholar

2. Grad J, Sainsbury P: The effects that patients have on their families in a community care and a control psychiatric service: a two-year follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 114:265-278, 1968Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Test M, Stein L: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: III. social cost. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:409-412, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hoult J, Reynolds I, Charbonneau-Powis M, et al: A controlled study of psychiatric hospital versus community treatment: the effect on relatives. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 15:323-328, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Reynolds I, Hoult J: The relatives of the mentally ill: a comparative trial of community-oriented and hospital-oriented psychiatric care. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 172:480-489, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Pharoah FM, Mari JJ, Streiner D: Family intervention for schizophrenia, Cochrane Review, in the Cochrane Library, vol 1. Oxford, Update Software, 2001Google Scholar

7. Szmukler G, Herrman H, Colusa S, et al: A controlled trial of counselling intervention for caregivers of relatives with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 31:149-155, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ziguras SJ, Stuart GW: A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of mental health case management over 20 years. Psychiatric Services 51:1410-1421, 2000Link, Google Scholar

9. Aberg-Wistedt A, Cressell T, Lidberg Y, et al: Two-year outcome of team-based intensive case management for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 46:1263-1266, 1995Link, Google Scholar

10. Chandler D, Meisel J, Hu TW, et al: Client outcomes in a three-year controlled study of an integrated service agency model. Psychiatric Services 47:1337-1343, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Szmukler GI, Wykes T, Parkman S: Care-giving and the impact on carers of a community mental health service. PRiSM Psychosis Study 6. British Journal of Psychiatry 173:399-403, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Fiander M, Burns T: Essential components of schizophrenia care: a Delphi approach. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 98:400-405, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. UK700 Group: Comparison of intensive and standard case management for patients with psychosis: rationale of the trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 174:74-78, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Francell CG, Conn VS, Gray DP: Families' perceptions of burden of care for chronic mentally ill relatives. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:1296-1300, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

15. UK700 Group: Intensive versus standard case management for severe psychotic illness: a randomised trial. Lancet 353:2185-2189, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Robins E: Research Diagnostic Criteria: rationale and reliability. Archives of General Psychiatry 35:773-782, 1978Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. McGuffin P, Farmer A, Harvey I: A polydiagnostic application of operational criteria in studies of psychotic illness: development and reliability of the OPCRIT system. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:764-770, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Burns T, Fiander M, Kent A, et al: Effects of case load size on the process of care of patients with severe psychotic illness: a report from the UK700 Trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 177:427-433, 2000Medline, Google Scholar

19. Szmukler G, Burgess P, Herrman H, et al: Caring for relatives with serious mental illness: the development of the Experience of Caregiving Inventory. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 31:137-148, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Goldberg D: The 12-Item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12). Windsor, England, NFER-NELSON, 1978Google Scholar

21. Goldberg D, Williams P: A User's Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, England, NFER-NELSON, 1988Google Scholar

22. Goodchild ME, Duncan-Jones P: Chronicity and the General Health Questionnaire. British Journal of Psychiatry 146:55-61, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, et al: The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO Study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine 27:191-197, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Jones SL, Roth D, Jones PK: Effect of demographic and behavioral variables on burden of caregivers of chronic mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 46:141-145, 1995Link, Google Scholar

25. Stueve A, Vine P, Struening EL: Perceived burden among caregivers of adults with serious mental illness: comparison of black, Hispanic, and white families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:199-209, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Baronet AM: Factors associated with caregiving burden in mental illness: a critical review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review 19:819-841, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Solomon P: Moving from psychoeducation to family education for families of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 47:1364-1370, 1996Link, Google Scholar

28. Department of Health: National Service Framework for Mental Health. Modern standards and service models. London: HMSO, 1999Google Scholar

29. Szmukler G: Family involvement in the care of people with psychoses: an ethical argument. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:401-405, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Bogart T, Solomon P: Procedures to share treatment information among mental health providers, consumers, and families. Psychiatric Services 50:1321-1325, 1999Link, Google Scholar