Mental Health Services in Nursing Homes: Models of Mental Health Services in Nursing Homes: A Review of the Literature

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors review the research literature on models and outcomes of extrinsic mental health services in nursing homes and summarize the data on current practices in this area. Extrinsic mental health services are those delivered in the nursing home by specialists who are not full-time staff of the nursing home. METHODS: English-language articles providing descriptive and research reports on models and outcomes of extrinsic mental health services in nursing homes were identified through a comprehensive search of peer-reviewed journals, using MEDLINE and psychological literature databases. The research methods of the reports were also noted. RESULTS: Three primary models of mental health service delivery were identified: psychiatrist-centered, nurse-centered, and multidisciplinary team models. Uncontrolled observational studies suggested that mental health services may result in improved clinical outcomes and less use of acute services. However, few well-designed controlled intervention studies have been conducted. Education and training appeared to improve staff members' knowledge and performance and to decrease turnover. The least effective model involoved traditional consultation-liaison service in which a lone clinician provided a one-time, written consultation on an as-needed basis. Multidisciplinary team approaches were favored as preferred service models. CONCLUSIONS: Few studies using an experimental design have examined the outcomes of mental health services in nursing homes. Program descriptions and uncontrolled outcome studies suggest that preferred practice includes the routine presence of qualified mental health clinicians in the nursing home, that optimal services are interdisciplinary and multidimensional, and that the most effective interventions blend innovative approaches to training and education with consultation and feedback on clinical practices.

Despite the high prevalence of psychiatric and behavioral problems among nursing home residents, most of those residents who need mental health services do not receive them. About 80 percent of nursing home residents have diagnosable psychiatric disorders, with dementia being the most prevalent condition (1,2,3). However, fewer than a fifth of them receive treatment from a mental health clinician (4,5). Nursing home staff have identified a lack of access to high-quality mental health services and a lack of appropriate reimbursement as major barriers to providing needed consultation services to nursing home residents (6). Nursing home administrators have estimated that two-fifths of nursing home residents need psychiatric services, yet half of nursing homes do not have access to adequate psychiatric consultation, and three-quarters are unable to obtain consultation and educational services for behavioral interventions (6). In general, there are not enough mental health clinicians with specialized training in geriatric psychiatry who are willing and able to provide mental health services in nursing homes (7).

Effective models of mental health service delivery in nursing homes will be critical in meeting the needs of the growing numbers of individuals who will be entering long-term-care facilities over the coming decades. In this report we provide an overview of the treatment research literature on extrinsic mental health services in nursing homes and summarize data on current practice in this area. Extrinsic mental health services are those provided on-site by specialists who are not full-time staff of the nursing home.

Three questions will be addressed. First, what is known about psychiatric practice in nursing homes? Second, what models of mental health services provided to nursing homes are described in the research literature? Finally, what outcomes of mental health services in nursing homes are reported in the literature?

Methods

We used MEDLINE and psychological literature databases to conduct a comprehensive search for English-language descriptive and research reports published through May 2000 on models of mental health services in nursing homes. We used a variety of search terms, including psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, mental disorders, long-term care, homes for the aged, nursing homes, and residential facilities. We also conducted a manual search of references from relevant literature. Our searches were restricted to articles in peer-reviewed journals reporting on models and outcomes of extrinsic mental health services as well as on hybrid services involving external psychiatric clinicians who work closely with nursing home psychiatric nurse specialists or social workers. Given our aim of describing the roles, models, and outcomes of mental health services provided by psychiatrists and other external clinicians, we excluded reports on mental health services provided by full-time nursing home staff or descriptions of special-care units or dementia-care units staffed by nursing home professionals. We also excluded non-nursing home settings, such as assisted living facilities and residential care homes, because the literature on these settings is poorly defined and their patient population and treatment and regulatory environment are different from those of nursing homes. Research methods were also noted, including narrative program descriptions, reports of outcome data, and studies using an experimental design. The sources reviewed included detailed descriptions of service models that lacked outcome data, observational outcome studies, and randomized controlled studies of mental health service interventions.

Results

Psychiatric practice in nursing homes

A recent survey of practitioners suggested that psychiatric services in nursing homes, if they are available, are most commonly provided by a psychiatric consultant who works alone, comes only when called to see a specific patient, and does not provide subsequent care unless specifically called back (8). This survey of clinicians, as well as a multistate survey of nursing home administrators (6), concluded that traditional, "as-needed" consultation models are inadequate to address the many needs of nursing home residents and staff. Available data on nursing home practices by mental health clinicians are largely limited to the results of surveys of general psychiatrists (9) and psychiatrists who specialize in geriatric psychiatry (10).

An annual practice survey of a randomly selected sample of general psychiatrists in the United States conducted from 1982 to 1996 has shown a gradual increase in the proportion of American psychiatrists who have a substantial geriatric practice (9). The proportion of psychiatrists for whom elderly patients constitute at least 20 percent of their caseload increased from 7.3 percent in 1982 to 14.5 percent in 1988 and then to 18.1 percent in 1996. This group of psychiatrists devoted 7 percent of their professional time to practice in nursing homes. Moreover, 14.9 percent had board certification with additional qualifications in geriatric psychiatry. In contrast, psychiatrists for whom elderly patients made up less than 20 percent of their caseload were unlikely to devote much time to nursing home practice, spending on average of only .5 percent of their time in nursing homes. These data suggest that despite trends showing an increase in the proportion of psychiatrists who treat older people, the vast majority of psychiatric practice in nursing homes is provided by a minority of clinicians who devote at least a fifth of their practice to geriatrics.

Not surprisingly, most psychiatrists who have a subspecialty in geriatrics routinely provided mental health services in nursing homes. Data from surveys conducted in 1997 by the Canadian Academy of Geriatric Psychiatry (10) and in 1998 by the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (8) have shown that more than three-quarters of geriatric psychiatrists saw patients in nursing homes. The Canadian survey revealed that 78 percent of respondents worked in nursing homes and that they provided services for an average of 5.8 institutions (10). Canadian geriatric psychiatrists reported that they spent, on average, 7.5 hours a week in nursing homes, which accounted for about a fifth of their professional time. Sixty-five percent reported that they worked within an interdisciplinary team structure.

The 1998 survey conducted by the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry found that geriatric psychiatrists in the United States visited six nursing homes on average (8), nearly the same proportion as their Canadian counterparts. At these facilities, they covered an average of 678 beds. At the primary nursing home where they worked, they spent an average of four hours per visit and saw nine residents for an average of 26 minutes per resident. Sixty-seven percent worked within a team consisting primarily of nurses (76 percent), social workers (62 percent), or psychologists (36 percent). This finding is comparable to the 65 percent of Canadian geriatric psychiatrists who reported working as part of a team. The most common treatment recommendations by geriatric psychiatrists in the U.S. survey included psychiatric medications (84 percent), changes in the general medical regimen (55 percent), staff support interventions (46 percent), medical diagnostic testing (37 percent), behavioral interventions (35 percent), staff training (30 percent), individual or group psychotherapy (20 percent), and family psychotherapy (13 percent). These data suggest that geriatric psychiatrists tend not to rely solely on pharmacotherapy, instead recommending a more diverse range of treatment interventions, as suggested by the treatment literature (11,12). This approach contrasted with the more typical pattern of exclusive reliance on pharmacotherapy that nursing home staff perceive to be inadequate (6).

Models of mental health services

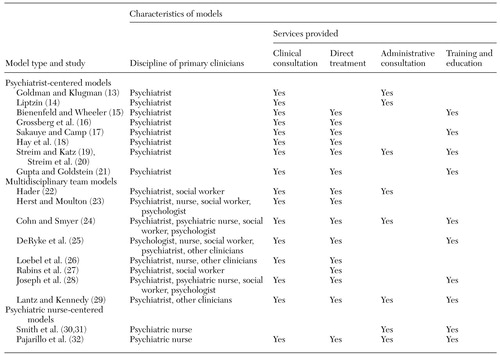

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of three models of mental health services in nursing homes—psychiatrist-centered models, multidisciplinary team models, and nurse-centered models. Psychiatrist-centered models emphasize the role of the psychiatrist as the primary and often the sole provider of direct consultation and clinical services (13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21). In this respect, the psychiatrist-centered model is an adaptation of the traditional hospital-based consultation-liaison model. In general, the psychiatrist responded to a request to provide clinical evaluation and treatment recommendations for a specific resident. Only a minority of the reports on this type of model included a description of administrative or program consultation provided to the nursing home managers, and only half explicitly described staff training and education.

In contrast, multidisciplinary team models included a variety of mental health clinicians with different roles and responsibilities (22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29). Teams varied in size from two individuals—for example, a psychiatrist and a social worker or another clinician—to as many as five clinicians, including a psychiatrist, a psychiatric nurse, a social worker, a psychologist, and other types of service providers. Most reports on these models described direct clinical consultation services to individual nursing home residents, and half described training and educational activities. Multidisciplinary team models emphasized the complementary contributions of different disciplines (24). For example, the psychiatric nurse specialist may be more effective in directly relating to the nursing staff and in developing treatment plans, and the psychiatrist may be most influential in relating to the medical director and physician staff and providing recommendations for differential diagnosis and pharmacological interventions. Psychologists may offer specific expertise in behavioral programming and neuropsychological assessment, whereas social workers may have superior skills in addressing family and social support concerns.

Finally, two reports described nurse-centered models of mental health service delivery that are distinguished by the presence of a geropsychiatric nurse specialist who coordinates the service of other extrinsic mental health clinicians while providing training to develop the skills and abilities of the intrinsic nursing staff. These nurse-centered models (30,31,32) emphasize routine administrative consultation to nursing home personnel and training of intrinsic direct care staff to provide mental health interventions within the nursing home. These models included a "train-the-trainer" approach in which an extrinsic geropsychiatric nurse specialist provides ongoing training and consultation to a nursing home staff nurse who becomes the internal "expert" responsible for training others.

Common themes among these models include an emphasis on the limitations of traditional consultation services provided on an as-needed or emergency basis. The reports emphasized the value of a team approach for providing ongoing routine services within the nursing home, ideally in the context of a formal contract for clinical, administrative, and training services.

Effectiveness of mental health services

Few studies of the outcomes of mental health services in nursing homes have been conducted, and most have substantial methodological limitations. For example, a majority were observational studies that did not include a comparison group, and, in most studies, outcomes were rated by clinicians.

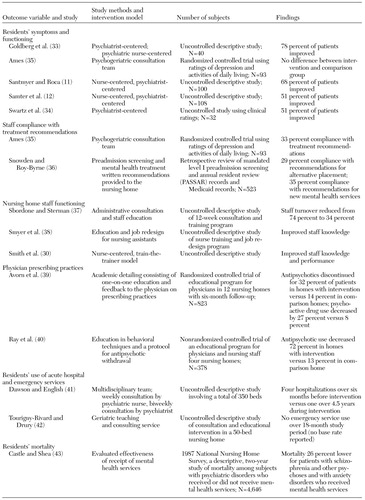

The findings of data-based studies are summarized in Table 2, with emphasis on four overall categories of outcomes: residents' symptoms and functioning, residents' use of acute services, functioning of the nursing home staff, and physicians' prescribing practices. The outcomes of mental health services on residents' symptoms and functioning have been reported in four uncontrolled descriptive studies with samples ranging from 32 to 108 persons. These studies found that mental health services were associated with improvement in symptoms and functioning among 51 to 78 percent of residents who received services (11,12,33,34). In contrast, the only randomized controlled study that examined these outcomes found no difference between nursing home residents who received psychogeriatric consultation services and a comparison group that received usual care (35). This study of 93 residents included ratings of depression and functional outcomes. Although no difference in outcomes was found for the group that received psychiatric consultation services, only a third (27 of 81) of the treatments recommended in the consultation intervention were implemented. The failure of nursing home staff to adopt the written treatment recommendations of external consultants and reviewers was also noted in a study that examined compliance with mandated preadmission screening and annual residence reviews (36). This review of the records of 523 nursing home residents found that only 35 percent of recommendations for new mental health services were followed.

Several studies have suggested that targeted educational interventions may be successful in changing clinicians' treatment practices. Three uncontrolled descriptive studies of specific training and educational programs found that the programs were associated with lower staff turnover (37) and improved knowledge and performance by nursing home staff (30,38). These studies emphasized the importance of focusing training on the staff members who have the greatest direct contact with residents, such as certified nursing assistants. Two different educational interventions have also been shown to be effective in changing the prescribing practices of physicians in nursing homes. In the first, a decrease in the use of antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications was found in a randomized trial of academic detailing consisting of one-on-one physician education and feedback on prescribing behavior (39). In the second, lower use of antipsychotics was achieved in a nonrandomized study of nursing staff and physician education in the use of behavioral techniques combined with a protocol for gradual withdrawal from antipsychotic medications (40).

Several observational studies have reported that mental health services in nursing homes may be associated with better outcomes, including lower rates of hospitalization (41) and lower use of emergency services (42). However, none of these studies reported baseline rates of service use for an equivalent period before the intervention. Caution is also warranted in interpreting these results because these studies did not report the methods for determining service use. Finally, an analysis of nursing home survey data suggested that mental health services may be associated with lower mortality rates among nursing home residents with specific psychiatric diagnoses (43). This descriptive two-year follow-up study of 1987 national nursing home survey data on 4,646 residents reported that among residents with psychiatric disorders, the mortality rate for those who received psychiatric services was 26 percent lower than the rate for those who did not. Notably, this difference was found only for residents with schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders. There were no differences between the groups for other diagnoses, such as depression, after the effects of resident and facility characteristics were controlled for (44).

In summary, the data on the effectiveness of mental health services in nursing homes are promising but have substantial methodological limitations. Uncontrolled observational studies have reported that one-half to three-quarters of residents who received mental health services improved and that mental health services may be associated with lower rates of hospitalization and lower use of emergency services. However, well-designed controlled studies are needed to confirm the effectiveness of mental health services in improving clinical outcomes and reducing use of acute services in nursing homes. Education and training appear to improve staff knowledge and performance and to decrease staff turnover. Innovative educational models are effective in changing physicians' prescribing behavior when ongoing monitoring and direct feedback are provided.

The literature suggests a general consensus that the least effective model consists of traditional consultation-liaison services in which a clinician provides written treatment recommendations on an as-needed basis. This approach appears to be ineffective because of poor treatment implementation, a lack of adherence to written recommendations, and a failure to provide additional services, including ongoing training, administrative consultation, program development, and discipline-specific support.

In contrast, multidisciplinary treatment team approaches appear to be favored in descriptions of preferred service models. However, these studies did not assess the cost-effectiveness of this model. Although researchers have argued that the combined use of physician and nonphysician services, including follow-up, may result in more efficient and effective services, data are lacking. In addition, evidence-based guidelines are needed to ensure that services are provided by qualified clinicians, are medically necessary, and have the appropriate intensity. The lack of cost-effectiveness data is particularly unfortunate in view of the recent controversial findings of the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services, which concluded that 27 percent of mental health services in nursing homes are medically unnecessary (44). Despite problems in the methods and interpretations of such regulatory studies, they underscore the urgent need to provide empirical support for recommended treatments and service models. Finally, some of the most promising models have focused on improving the behavioral management skills and treatment behaviors of the nursing home staff though training and discipline-specific interventions.

Discussion

What conclusions can be drawn about the characteristics and effectiveness of optimal models of mental health service delivery in nursing homes? First, the available research literature is marked by a paucity of well-designed studies that use a sufficient test of effectiveness. Many reports describe programs but lack outcome measures. With few exceptions, the studies that used outcome measures did not use a controlled design with a comparison group. Overall, we were able to identify only two randomized controlled studies of service interventions. One study tested the effectiveness of psychogeriatric consultation in a small sample and found inadequate implementation of treatment recommendations (35). The other focused on physicians' prescribing practices and reported that a targeted educational and feedback intervention provided significant benefits (39).

Despite substantial limitations in the current research literature, a clear convergence on several points can be discerned in the descriptions of service models and the findings of outcome studies. First, these reports recommend the routine presence of qualified mental health clinicians in the nursing home. A regular presence allows mental health clinicians to provide ongoing consultation and follow-up during episodes of acute illness and to provide an intensity of services dictated by medical necessity. Other elements of good care may include routine subsequent visits by mental health clinicians for management of maintenance treatment and for administrative and programmatic consultation to the facility and its staff. The most appropriate intensity of services is still unclear. Variations in the intensity of services are likely to be driven by factors such as practice structure, demand for services, patterns of reimbursement, and geography in addition to medical necessity.

Second, optimal services are interdisciplinary and multidimensional, addressing neuropsychiatric, medical, psychosocial, environmental, and staff issues. Most of the models described in the literature are team models, and a majority of geriatric psychiatrists who are members of the Canadian and American associations of geriatric psychiatrists practice within a team structure. However, the ideal composition of the team is not well defined, and it is not clear whether the interdisciplinary team must be formally organized or whether it can function through collaboration between extrinsic consultants and specially trained on-site nursing home staff.

Third, among the most effective interventions are those that blend consultation with training and educational interventions. Training and education should focus on frontline nursing staff who provide basic care to residents as well as on nursing home physicians who are responsible for prescribing psychotropic medications and behavioral interventions.

Conclusions

Well-designed intervention and services research studies are needed to determine which psychiatric treatments are most effective in the nursing home, which disciplines should provide such treatments, what competencies are crucial for nursing home staff, and which interventions are the most cost-effective. These findings will form the basis of changes in regulatory and reimbursement policies to support more effective and efficient mental health services in long-term care.

Dr. Bartels is director of the aging services division of the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center and associate professor of psychiatry at Dartmouth Medical School in Hanover, New Hampshire. Dr. Moak is associate professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester. Ms. Dums is a research assistant in the aging services division of the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center. Send correspondence to Dr. Bartels, New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, 2 Whipple Place, Suite 202, Lebanon, New Hampshire 03766 (e-mail, [email protected]). This study was presented in part at the long-term care consensus conference of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry held June 22-24, 2000, in Washington, D.C. This article is part of a special section on mental health services in long-term care facilities.

|

Table 1. Studies describing models of mental health service delivery in nursing homes

|

Table 2. Outcomes of mental health service interventions and models in nursing homes

1. Rovner BW, German PS, Brodhead J, et al: The prevalence and management of dementia and other psychiatric disorders in nursing homes. International Psychogeriatrics 2:13-24, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Tariot PN, Podgorski CA, Blazina L, et al: Mental disorders in the nursing home: another perspective. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1063-1069, 1993Link, Google Scholar

3. Krauss NA, Freiman MP, Rhoades JA, et al: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, Nursing Home Update, 1996, AHCPR publication 97-0036. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1997Google Scholar

4. Shea DG, Streit A, Smyer MA: Determinants of the use of specialist mental health services by nursing home residents. Health Services Research 29:169-185, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

5. Smyer MA, Shea DG, Streit A: The provision and use of mental health services in nursing homes: results from the National Medical Expenditure Survey. American Journal of Public Health 84:284-287, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Reichman WE, Coyne AC, Borson S, et al: Psychiatric consultation in the nursing home: a survey of six states. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 6:320-327, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

7. Lombardo NE, Sherwood S: The 1992 National Telephone Survey of Nursing Home Administrators and Directors of Nursing. Boston, Research and Training Institute, Hebrew Rehabilitation Center for Aged, 1992Google Scholar

8. Moak GS, Borson S, Jackson J: The AAGP Long Term Care Survey. Paper presented at the long-term care consensus conference of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, Washington, DC, June 22-24, 2000Google Scholar

9. Colenda CC, Pincus H, Tanielian TL, et al: Update of geriatric psychiatry practices among American psychiatrists. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 7:279-288, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

10. Conn D, Silver I: The psychiatrist's role in long-term care. Canadian Nursing Home 9:22-24, 1998Google Scholar

11. Santmyer KS, Roca RP: Geropsychiatry in long-term care: a nurse-centered approach. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 39:156-159, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Samter J, Braun JV, Culpepper WJ, et al: Description of a program for psychiatric consultations in the nursing home. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 2:144-156, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Goldman LS, Klugman A: Psychiatric consultation in a teaching nursing home. Psychosomatics 31:277-281, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Liptzin B: The geriatric psychiatrist's role as consultant. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 16:103-112, 1983Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bienenfeld D, Wheeler BG: Psychiatric services to nursing homes: a liaison model. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:793-794, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Grossberg GT, Hassan R, Szwabo PA, et al: Psychiatric problems in the nursing home. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 38:907-917, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Sakauye KM, Camp CJ: Introducing psychiatric care into nursing homes. Gerontologist 32:849-852, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Hay DP, Hay L, Howell T, et al: Geriatric psychiatry consultation for nursing homes. Nursing Home Medicine 4:178-184, 1994Google Scholar

19. Streim JE, Katz IR: The psychiatrist in the nursing home: II. consultation, primary care, and leadership. Psychiatric Services 46:339-341, 1995Link, Google Scholar

20. Streim JE, Oslin D, Katz IR, et al: Lessons from geriatric psychiatry in the long-term care setting. Psychiatric Quarterly 68:281-307, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Gupta S, Goldstein MZ: Psychiatric consultation to nursing homes. Psychiatric Services 50:1547-1550, 1999Link, Google Scholar

22. Hader M: The psychiatrist as consultant to the social worker in a home for the aged. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 14:407-413, 1966Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Herst L, Moulton P: Psychiatry in the nursing home. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 8:551-561, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Cohn MD, Smyer MA: Mental health consultation: process, professions, and models, in Mental Health Consultation in Nursing Homes. Edited by Smyer MA, Cohn MD, Brannon D. New York, New York University Press, 1988Google Scholar

25. DeRyke SC, Wieland D, Wendland CJ, et al: Psychologists serving elderly in long-term care facilities. Clinical Gerontologist 10:35-49, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

26. Loebel JP, Borson S, Hyde T, et al: Relationships between requests for psychiatric consultation and psychiatric diagnoses in long-term-care facilities. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:898-903, 1991Link, Google Scholar

27. Rabins P, Storer D, Lawrence MP: Psychiatric consultation to a continuing care retirement community. Gerontologist 32:126-128, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Joseph C, Goldsmith S, Rooney A, et al: An interdisciplinary mental health consultation team in a nursing home. Gerontologist 35:836-839, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Lantz MS, Kennedy GJ: The psychiatrist in the nursing home: I. collaborative roles. Psychiatric Services 46:15-16, 1995Link, Google Scholar

30. Smith M, Mitchell S, Buckwalter KC, et al: Geropsychiatric nursing consultation: a valuable resource in rural long-term care. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 8:272-279, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Smith M, Mitchell S, Buckwalter KC: Nurses helping nurses: development of internal specialists in long-term care. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 33:38-42, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

32. Pajarillo EJ, Sers AJ, Ryan RM, et al: Consultation-liaison psychiatric nursing in long-term care. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 35:24-30, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

33. Goldberg HL, Latif J, Abrams S: Psychiatric consultation: a strategic service to nursing home staffs. Gerontologist 10:221-224, 1970Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Swartz M, Martin T, Martin M, et al: Outcome of psychogeriatric intervention in an old-age home: a 3 year follow-up study. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 11:109-112, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Ames D: Depression among elderly residents of local-authority residential homes: its nature and the efficacy of intervention. British Journal of Psychiatry 156:667-675, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Snowden M, Roy-Byrne P: Mental illness and nursing home reform: OBRA-87 ten years later. Psychiatric Services 49:229-233, 1998Link, Google Scholar

37. Sbordone RJ, Sterman LT: The psychologist as a consultant in a nursing home: effect on staff morale and turnover. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 14:240-250, 1983Crossref, Google Scholar

38. Smyer M, Brannon D, Cohn M: Improving nursing home care through training and job redesign. Gerontologist 33:327-333, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

39. Avorn J, Soumerai SB, Everitt DE, et al: A randomized trial of a program to reduce the use of psychoactive drugs in nursing homes. New England Journal of Medicine 327:168-173, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Ray WA, Taylor JA, Meador KG, et al: Reducing antipsychotic drug use in nursing homes: a controlled trial of provider education. Archives of Internal Medicine 153:713-721, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

41. Dawson D, English C: Psychiatric consultation and teaching in a home for the aged. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 26:509-511, 1975Link, Google Scholar

42. Tourigny-Rivard MF, Drury M: The effects of monthly psychiatric consultation in a nursing home. Gerontologist 27:363-366, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Castle NG, Shea DG: Mental health services and the mortality of nursing home residents. Journal of Aging and Health 9:498-513, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Medicare Payments for Psychiatric Services in Nursing Homes: A Follow-Up. Publication OIE-02-99-00140. Rockville, Md, Office of the Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services, 2001Google Scholar