Problematic Substance Use, Depressive Symptoms, and Gender in Primary Care

Abstract

This study determined the frequency of problematic substance use and of counseling about drug and alcohol use among 867 women and 320 men who reported symptoms of depression in managed primary care clinics. Seventy-two (8.3 percent) of the women and 61 (19 percent) of the men reported hazardous drinking; 228 (26.3 percent) of the women and 94 (29.4 percent) of the men reported problematic drug use, including use of illicit drugs and misuse of prescription drugs. Only 17 (13.9 percent) of the patients who reported hazardous drinking and 18 (6.6 percent) of those who reported problematic drug use received counseling about drug or alcohol use during their last primary care visit. Men were significantly more likely than women to have received counseling about drug or alcohol use from their primary care practitioner.

Recent years have seen extensive efforts to raise awareness of depression and improve the treatment of depression in primary care, but substance use disorders and comorbid depression have not received the same attention. Substance use is underrecognized in primary care settings, particularly among women, for whom treatment is considered more complicated and difficult (1). Differences have been found between men and women in the nature and progression of addiction, which may affect the identification and treatment of this problem among women (2,3).

Problematic use of alcohol and drugs affects the diagnosis and treatment of depression and requires its own evaluation and treatment. Because most persons who abuse substances do not seek specialty care, primary care providers have an important responsibility to identify, treat, and monitor these individuals. In this study, we used a large database from a survey of six managed primary care organizations to estimate the frequency of problematic alcohol and drug use among male and female patients who had depressive symptoms and whether they received advice or counseling on alcohol or drug use at their last medical visit. We hypothesized, on the basis of published studies, that alcohol and drug use would be higher among men than among women and that women would be less likely to receive counseling on drug or alcohol use than men.

Methods

We used data from a survey of 46 clinics associated with six managed care organizations in Maryland, Minnesota, California, Texas, and Colorado. These organizations were part of a study of alternative interventions to improve the quality of care for depression and included public, private, staff, and network practice models in urban, suburban, and rural areas (4).

Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they were at least 18 years old, spoke English or Spanish, considered the clinic to be their primary source of medical care, and had health insurance that covered care from behavioral health care providers that offered the alternative interventions. Patients who had comorbid medical or psychiatric illnesses were also eligible.

Patients were identified as having a probable current depressive disorder if they received a positive score on a five-item screening instrument that was based on the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview 2.1, 12-month version (CIDI-12 2.1) (5) and had had symptoms of depression in the previous month. Of 27,332 consecutive patients, 3,918 met the eligibility criteria, and 1,356 enrolled in the two-year study between June 1996 and March 1997. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. Enrolled patients completed the full affective disorders section of the CIDI-12 2.1 (response rate, 100 percent) and a baseline patient assessment questionnaire (response rate, 1,193 patients, or 88 percent). The analytic sample consisted of 1,187 patients who completed the baseline questionnaire and for whom data on problematic substance use were available.

To measure hazardous or at-risk drinking, we used the ten-question Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Hazardous drinking is defined as consumption of alcohol in a quantity or pattern that places patients at risk of adverse health events, such as physical or psychological harm (6). A cutoff score of 8 out of a possible score of 40 points has a sensitivity of 96 percent and specificity of 98 percent for hazardous alcohol consumption (7,8). Problematic drug use was defined as use of any illicit drug or drug use without a physician's prescription in the previous six months, use in greater amounts or more often than prescribed, or use for a reason other than advice from a physician. The patients were asked whether a health care provider had given advice or counseling about alcohol or drug use during their last medical visit.

We calculated the percentage of patients who engaged in problematic substance use and the percentage who received counseling on drug or alcohol use. We weighted the data to correct for the varying probabilities of enrollment among clinic patients, attrition, and survey response rates. We used the chi square statistic to test for differences between men and women and used logistic regression to analyze the relationship of gender and depressive disorder to the likelihood of receiving counseling. Missing data at the item level, except the outcome variable for counseling, were imputed by use of a hot deck imputation method (9).

Results

Of the 1,187 patients, 867 (73 percent) were women; 311 (26 percent) were Hispanic, 716 (60.3 percent) were white, 80 (6.7 percent) were African American, and 80 (6.7 percent) were of other minorities. The patients' ages ranged from 18 to 90 years (median, 43 years). A total of 473 patients (39.9 percent) had a diagnosis of major depression or dysthymia, and 714 patients (60.1 percent) had depressive symptoms that did not meet the criteria for dysthymia or major depression.

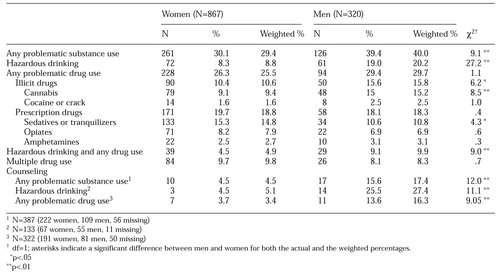

As shown in Table 1, a total of 261 (30.1 percent) of the women and 126 (39.4 percent) of the men reported problematic substance use. Hazardous drinking was less common among women than among men. More than a quarter of the sample used illicit drugs or misused prescription drugs; no significant differences in problematic drug use were found between women and men. Overall use of illicit drugs and use of cannabis were significantly lower among women. Misuse of prescription drugs was similar for women and men, but misuse of sedatives or tranquilizers was significantly higher among women.

Among the 387 patients who reported either hazardous drinking or problematic drug use, 27 (8.2 percent) had received counseling; men were significantly more likely to have received counseling (17 men, or 15.6 percent, versus 10 women, or 4.5 percent). Of the 133 patients who reported hazardous drinking, 17 (13.9 percent) reported receiving counseling—14 of the men (25.5 percent) and 3 (4.5 percent) of the women. Among hazardous drinkers, women were less likely to have received counseling when age was controlled for (odds ratio=.19, p=.026). Among the 322 patients who had used an illicit drug or misused a prescription drug, 18 (6.6 percent) had received counseling—11 of the men (13.6 percent) and 7 of the women (3.7 percent). Among the patients who used illicit drugs and those who misused prescription drugs, women were also less likely to have received counseling when age was controlled for (odds ratio=.18, p=.001). When gender was controlled for, the presence of a depressive disorder was not significantly associated with hazardous drinking or problematic drug use.

Discussion

In this sample of primary care patients who had depression, hazardous drinking or problematic drug use was reported by more than 30 percent of both the men and the women. Although women with symptoms of depression were less likely to have problems with alcohol or cannabis, they were more likely to misuse sedatives. The combination of problematic alcohol and drug use was more common among men who had depressive symptoms, but men and women did not differ significantly in problematic use of more than one drug.

The fact that relatively few of the patients in this study received advice or counseling on alcohol or drug use is striking, as is the difference in counseling rates between men and women. The overall rate of counseling related to substance use was low among patients who had depressive symptoms and was even lower among women. In studies conducted in the 1980s, primary care providers detected or treated substance abuse among only a few of their patients, and patients who abused substances were less likely to be identified if they were depressed (10). Alcohol abuse and illicit drug use may still carry more stigma for women than for men, which may discourage women from seeking help from a health care provider and thus may hamper detection of substance abuse problems.

This study had several limitations. First, substance use may have been underreported because the study relied on self-reports. On the other hand, consecutive sampling of patients who visited the clinic may have resulted in oversampling of patients who visited the clinic more frequently, who were more ill, and who had more problematic substance use. Second, the enrollment process may have been biased, because patients with substance use problems may have been less likely to enroll. Third, to improve generalizability, the results were weighted. Finally, we did not have information about whether patients had participated in a specialty care program for problematic substance use or had previously discussed substance use with their provider. However, given that substance dependence is a chronic condition that is characterized by frequent relapses and that has significant medical and psychosocial implications, including drug interactions, providers have much to contribute to the care of individuals who have or are at risk of developing a substance use problem.

Conclusions

Problematic substance use is common among primary care patients who have depressive symptoms, but few patients—particularly women—receive advice or counseling about substance use from their primary care provider. Future research should focus on methods of improving screening, counseling, and treatment for both depression and substance use problems among men and women, including referral to or consultation with substance abuse or mental health specialists.

Acknowledgments

Financial support for this study was provided through grants MH-54623 and MH-0090 from the National Institute of Mental Health and grant HS-08349 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and by the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey. The authors acknowledge Diana Liao, M.P.H., and Jennifer Liu, B.S., for statistical assistance.

Dr. Roeloffs, Dr. Unützer, Dr. Tang, and Dr. Wells are affiliated with the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences of the Neuropsychiatric Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles, 10920 Wilshire Boulevard, Suite 300, Los Angeles, California 90024 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Wells is also affiliated with Rand in Santa Monica, California. Dr. Fink is with the department of medicine in the School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles.

|

Table 1. Problematic substance use and counseling on substance use among 1,187 primary care patients with depression

1. Moore RD, Malitz FE: Underdiagnosis of alcoholism by residents in an ambulatory medical practice. Journal of Medical Education 61:46-52, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

2. Piazza NJ, Vrbka JL, Yeager RD: Telescoping of alcoholism in women alcoholics. International Journal of Addiction 24:19-28, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, et al: Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:313-321, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wells KB: The design of Partners in Care: evaluating the cost-effectiveness of improving care for depression in primary care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:20-29, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), version 2.1. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1995Google Scholar

6. Reid MC, Fiellin DA, O'Connor PG: Hazardous and harmful alcohol consumption in primary care. Archives of Internal Medicine 159:1681-1689, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Saunders JB, Aasland OG: World Health Organization Collaborative Project on the Identification and Treatment of Persons With Harmful Alcohol Consumption: Report on Phase I: Development of a Screening Instrument. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1987Google Scholar

8. Conigrave KM, Hall WD, Saunders JB: The AUDIT questionnaire: choosing a cut-off score. Addiction 90:1349-1356, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Little RJ: Missing-data adjustments in large surveys. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 6:287-301, 1988Google Scholar

10. Coulehan JL, Zettler-Segal MS, Block M, et al: Recognition of alcoholism and substance abuse in primary care patients. Archives of Internal Medicine 147:349-352, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar