The Relationship Between Treatment Access and Spending in a Managed Behavioral Health Organization

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study replicated an earlier study that showed a linear relationship between level of treatment access and behavioral health spending. The study reported here examined whether this relationship varies by important characteristics of behavioral health plans. METHODS: Access rates and total spending over a five- to seven-year period were computed for 30 behavioral health plans. Regression analysis was used to estimate the relationship between access and spending and to examine whether it varied with the characteristics of benefit plans. RESULTS: A linear relationship was found between level of treatment access and behavioral health spending. However, the relationship closely paralleled that found in the earlier study only for benefit plans with an employee assistance program linked to the managed behavioral health organization and for plans that do not allow the use of out-of-network providers. CONCLUSIONS: The results of this study replicate those of the earlier study in showing a linear relationship between access and spending, but they suggest that the magnitude of this relationship may vary according to key plan characteristics.

Concerns about the effects of managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) have given rise to various attempts to understand the relationship between the amount of money spent on health care and the amount and quality of care that is delivered to consumers (1,2,3,4). In this arena, the usual market dynamics for most commodities are complicated by the fact that purchasers of health insurance are often employers who have difficulty determining the value of behavioral health care to their employees. Without some knowledge of the relationship between the cost of health care and the value of what is delivered, purchasers cannot rationally choose among competing behavioral health plans or even determine how much behavioral health care to purchase.

A recent study by Weissman and colleagues (5) provided some information about the value of behavioral health spending. The authors estimated the relationship between overall health care spending and the proportion of the population that received treatment—referred to as the treated prevalence rate—using secondary data from published articles on managed behavioral health. The results of that study suggest that each dollar increase in the amount spent on mental health and substance abuse treatment purchases services for an additional .9 percent of the population.

The study further showed that the relationship between spending and treated prevalence was linear and that it might be used by purchasers and MBHOs to project the level of treatment access that can be expected from a given level of spending.

Although the treated prevalence rate measures only one aspect of a health care system's performance, it gains additional significance through epidemiological and health services research on the rates of specialty mental health services use in the United States, which have been estimated at 5.6 to 5.9 percent in the general population (6,7). According to the study by Weissman and colleagues (5), an estimated $6 per member per month is required to achieve this level of access. Spending less than this amount may indicate greater restriction of access to care and possible undertreatment.

The study reported here was undertaken to determine whether the results obtained in the Weissman study are replicable in a broader sample of behavioral health plans and whether there are any important mediators in the relationship between spending and treated prevalence. We used data from a sample of 30 behavioral health plans from one MBHO and tested whether the relationship observed in the Weissman study differed by three key plan characteristics: the presence of capitation, allowance of out-of-network use, and integration of employee assistance programs and behavioral health benefits.

Method

Data source

Claims and benefit data were extracted from United Behavioral Health's 1998 data systems for 30 behavioral health benefit plans. The plans were for self-insured employers and included all contracts of five to seven years' duration. The contracts covered the years 1992 to 1998. Employers from a broad range of company sizes, types of industries, and geographic locations were represented. The details of the plans have been published elsewhere (8).

The total sample consisted of 179 observations—30 employer plans multiplied by 5.97 years per plan. The average monthly membership in the plans was 263,052, yielding 1.54 million person-years (number of persons multiplied by years of eligibility). A total of 59,005 persons were seen in treatment during the study period.

Characteristics of the plans

Behavioral health plans in managed settings differ from each other in a number of fundamental ways that affect how the plans are administered. For example, all plans are based on an individual practice association model in which a network of providers delivers services. However, point-of-service plans reduce payment for treatment that is delivered by out-of-network providers, and exclusive-provider plans do not pay for out-of-network treatment at all.

Plans also differ in the method by which employers pay the MBHO. Capitated (fully insured) plans place financial risk on the MBHO; employers pay on a per-member per-month basis. Here, capitation is distinguished from subcapitation, which passes financial risk through to mental health professionals. (United Behavioral Health does not make subcapitation arrangements with mental health professionals even when the plan is capitated by employers.) In administrative-services-only plans, employers pay for the direct costs of treatment and pay the MBHO an administrative fee for managing the benefit plan.

The final distinction is the type of employee assistance program offered by the employer. Employee assistance programs are specialized programs designed to provide early intervention and a broad range of assistance with life problems experienced by employees, spouses, and dependents. Assistance may be in the form of advice, use of community resources, child or elder care, referral for legal or social assistance, and in many cases behavioral health treatment. Program benefits pay for three to eight sessions at no cost to users. For persons requiring more treatment, additional sessions are paid for out of the usual mental health or substance abuse treatment benefit.

In some cases, employers purchase services through the MBHO. These plans are often referred to as integrated employee assistance programs because the program benefit is integrated with the managed behavioral health benefit and often represents the first few sessions of treatment. In other cases, the employee assistance program is not integrated with the behavioral health benefit, as when employers offer their own "internal" employee assistance program or purchase the program through another vendor.

Statistical analyses

Ordinary least-squares regression was used to examine the relationship between total spending for mental health and substance abuse treatment and treated prevalence. Spending included payment for employee assistance program services when the program was offered through the MBHO (integrated programs).

The basic statistical model regressed treated prevalence onto per-member per-month spending, as was done in the Weissman study. The model was enhanced by adding interaction terms that allowed separate regression lines to be estimated for plans with different benefit characteristics. Fitting separate regression lines for each group of benefit plans allowed us to compare the intercepts and slopes for exclusive-provider plans versus point-of-service plans, capitated versus administrative-services-only plans, and integrated versus nonintegrated employment assistance programs.

Results

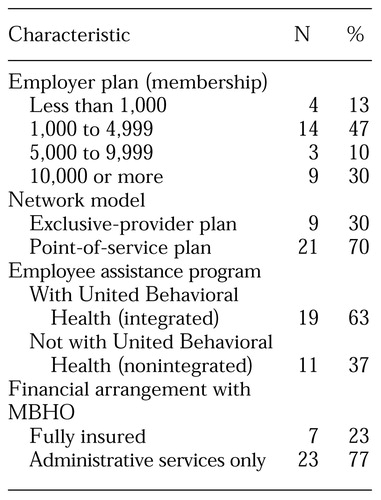

The basic characteristics of the 30 plans are presented in Table 1. The typical plan was a point-of-service plan paid through an administrative-services-only contract with an integrated employee assistance program.

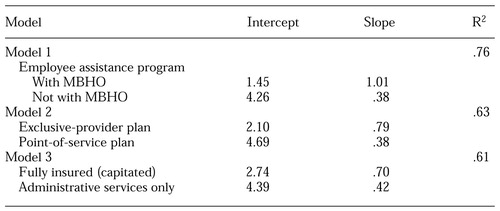

Regression results for models containing the variables for employee assistance programs, exclusive-provider plans, and fully insured plans are presented in Table 2. The employee assistance programs (model 1) produced the best-fitting regression model, with more than 75 percent of the variance in access rates accounted for by the model.

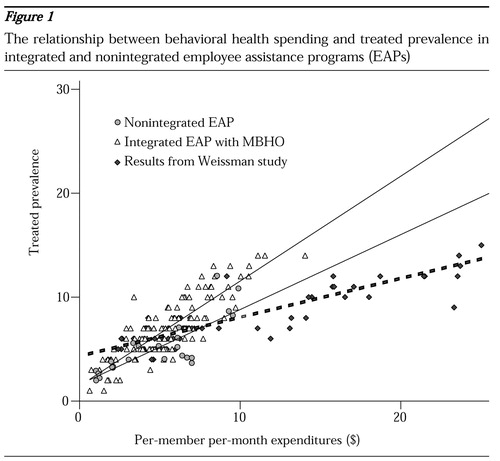

As in the Weissman study, each dollar increase in the per-member per-month variable was associated with a 1 percent increase in the treated prevalence rate when the employee assistance plan was integrated with the MBHO. When employee assistance programs were not integrated with the MBHO, each dollar increase in the per-member per-month variable purchased treatment for only .38 percent of the population. The relationships for integrated and nonintegrated employee assistance programs are plotted in Figure 1 along with the data reported in the Weissman study.

The relationship between spending and access also appeared to be modified in the exclusive-provider plans, although the R2 for model 2 was substantially less than that for model 1 (Table 2). Among exclusive-provider plans, each dollar increase in the per-member per-month expenditure purchased treatment for another .79 percent of the population. Among plans that allow use of out-of-network services, treated prevalence increased about half as much (.38 percent) for each dollar increase in the per-member per-month variable.

The access-spending relationship was not modified in capitated risk arrangements between employer and MBHO, as shown in model 3 (Table 2).

Discussion and conclusions

This study addressed one aspect of a fundamental question faced by public and private purchasers of behavioral health services: What is the relationship between the amount spent and the value of what is delivered? Although we are a long way from producing a satisfactory answer to this question, we suggest that access is an important quality indicator.

Our results replicate those of Weissman and colleagues (5), which suggest that behavioral health spending is strongly and linearly related to the proportion of people treated in a population. The Weissman study found that each additional dollar spent per member per month purchased behavioral health care for an additional .9 percent of the population; our study found that this figure may be as high as 1 percent among plans with an integrated employee assistance program and as low as .38 percent among plans with a nonintegrated employee assistance program.

Some of the differences observed in our study, such as the higher treated prevalence rate, may be attributable to the manner in which plans were selected for the two studies. The Weissman study relied on published estimates, whereas we used data from long-standing employer plans in a single MBHO. Plans with more MBHO experience tend to be able to treat a greater proportion of the population for a given dollar amount (9).

Other differences between the results of the two studies, such as the findings for benefit plans with a nonintegrated employee assistance program, are not well understood. Providers in employee assistance programs are frequently involved in the early course of treatment, which may affect how MBHOs manage the care of patients after their transition from the employee assistance program to the mental health provider. The transition of individuals from an employee assistance program to a mental health benefit may be more seamless and efficient, resulting in lower cost per person treated and providing other benefits to the consumer as well.

In addition, this study found that the relationship between access and spending was significantly different in benefit plans that allow use of nonnetwork providers. Each dollar spent on such plans purchased treatment for a smaller proportion of the population than in plans requiring the use of network providers. Finally, risk contracts with the MBHO, in the form of capitation payments, did not differ from administrative-services-only contracts in terms of the access-spending relationship, a finding consistent with other studies of risk sharing with MBHOs (10).

The results of the Weissman study and our study, combined with information about the prevalence of mental disorders in the general population, suggest ways of linking behavioral health care purchasing and management decisions to the real-world consequences of those decisions. The Weissman study suggests that if the expected rate of specialty mental health treatment is approximately 6 percent, then expenditures of significantly less than $6 per member per month may be inadequate. Our study found somewhat lower cost estimates, ranging from $4.50 to $4.70, depending on whether employee assistance program services are integrated as part of the mental health benefit.

Employers who spend significantly less than $4.50 per member per month for mental health and substance abuse treatment may want to examine their treated prevalence rate and address some basic questions: Are the low costs associated with this benefit plan showing up somewhere else, such as in high short-term disability or medical costs? Are there any unintended administrative or financial barriers to early access to mental health and substance abuse treatment that can be removed? What undertreated groups exist and what proactive steps—employee assistance programs and outreach services, for example—might be taken to increase appropriate access for these groups?

The answers to these questions will depend on many factors, including the goals and objectives of the employer, the characteristics of the insured population, the training and availability of clinicians in the service system, and many aspects of how the benefit plan is administered and managed. The influence of employer and population factors can be seen in this study, in which considerable variation was observed in treated prevalence rates and spending across plans, even though all the plans were administered within the same operational division of the same MBHO.

It is important to note that the variation within a single MBHO seen in this study matched or exceeded the variation across MBHOs seen in the Weissman study. Consequently, these results cannot be used to set generalizable thresholds for spending, despite the strong and linear relationships observed in this study.

Clearly, treated prevalence is only one indicator of the value of care delivered within a system. Ready access to behavioral health services that are inadequate in amount and type creates no value for purchasers or consumers. Ideally, purchasers would have information that allowed them to understand the quality of care purchased for each dollar in much more meaningful terms, such as the amount of suffering alleviated and the number of people restored to active and productive lives. Such knowledge is not only far beyond the capacity of current information systems, but it would also require a level of cooperation among consumers, providers, employers, and MBHOs that does not exist today. At the very least, we need information systems and cooperative agreements that allow sharing of data on the nature and outcomes of mental health care in a manner that ensures the confidentiality of information about consumers.

Additional studies are needed to confirm or modify the findings of this study. In particular, more information is needed on the relationship between behavioral health spending and other system-level measures of the value of care purchased, such as degree of patient improvement and the concordance of care with current best-practice treatment guidelines.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Danah Kozma, M.P.H., and Joyce McCulloch, M.S., for preparing the data and William Goldman, M.D., and Sharon Fusco, M.F.C.C., C.E.A.P., for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Dr. Cuffel is vice-president of research and evaluation at United Behavioral Health, 425 Market Street, 27th Floor, San Francisco, California 94010 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Regier is executive director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education of the American Psychiatric Association in Washington, D.C.

Figure 1. The relationship between behavioral health spending and treated prevalence in integrated and nonintegrated employee assistance programs (EAPs)

|

Table 1. Basic characteristics of the 30 behavioral health plans sampled from a managed behavioral health organization

|

Table 2. Comparison of three regression models of the relationship between spending and access to care in 30 managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs)

1. Frank RG, McGuire TG, Normand SL, et al: The value of mental health care at the system level: the case of treating depression. Health Affairs 18(5):71-88, 1999Google Scholar

2. Rosenheck RA, Druss B, Stolar M, et al: Effect of declining mental health service use on employees of a large corporation. Health Affairs 18(5):193-203, 1999Google Scholar

3. Merrick EL, Garnick D, Horgan CM, et al: Use of performance standards in behavioral health carve-out contracts among Fortune 500 firms. American Journal of Managed Care 5:SP81-SP90, 1999Google Scholar

4. Leslie DL, Rosenheck R: Shifting to outpatient care? Mental health care use and cost under private insurance. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1250-1257, 1999Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Weissman E, Pettigrew K, Sotsky S, et al: The cost of access to mental health services in managed care. Psychiatric Services 51:664-666, 2000Link, Google Scholar

6. Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, et al: The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: Epidemiologic Catchment Area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry 50:85-94, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Kessler RC, Frank RG, Edlund M, et al: Differences in the use of psychiatric outpatient services between the United States and Ontario. New England Journal of Medicine 336:551-557, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Cuffel BJ, et al: More evidence for the insurability of managed behavioral health care. Health Affairs 18(5):172-181, 1999Google Scholar

9. Sturm R: Cost and quality trends under managed care: is there a learning curve in behavioral health carve-out plans? Journal of Health Economics 18:593-604, 1999Google Scholar

10. Sturm R: How does risk sharing between employers and a managed behavioral health organization affect mental health care? Health Services Research 35:761-776, 2000Google Scholar