Economic Grand Rounds: The Costs of Parity Mandates for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Insurance Benefits

Employer-sponsored health plans typically provide less coverage for mental health and substance abuse treatment than for medical or surgical treatment. Inpatient coverage for most employees at medium and large firms is limited to 30 to 60 days per year for problems related to mental health and substance abuse, compared with 120 days or no limit for physical illnesses (1).

The merits and costs of mandating parity between insurance benefits for mental health and substance abuse treatment and benefits for medical or surgical treatment have been a recent topic of significant public debate. Since 1994 the U.S. Congress and more than 40 states have considered parity bills, and more than 20 states currently mandate parity for some or all mental health and substance abuse services. In 2001, health plans that participate in the Federal Employees Health Benefits program will be required to offer parity in patient cost sharing and service limits, such as the number of outpatient visits covered.

There are no federal mandates requiring parity for private-sector, employer-sponsored health plans with respect to cost sharing or service limits. However, a number of bills have been proposed. For example, in 1996 Senators Domenici and Wellstone proposed a bill that would have required parity for all mental illnesses. The bill did not pass, in part because some actuarial studies indicated that the proposal would substantially increase health insurance costs—according to one study by as much as 8.7 percent.

Instead, the federal government passed the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996, which mandates limited parity for mental health coverage. This act requires that, starting January 1, 1998, insurers provide the same annual and lifetime spending limits for mental health benefits as they do for other health care benefits. Companies with 50 or fewer employees are exempt, as are companies for which compliance would result in an increase of 1 percent or more in health insurance expenses. The mandate does not require employers to cover mental health treatment. In addition, it does not cover treatment for substance abuse, nor does it require parity with respect to cost sharing, the number of visits to mental health and substance abuse treatment providers, or the number of days in the hospital. Two actuarial studies conducted in 1996 estimated that the mandate would increase health insurance premiums by less than one-half of 1 percent.

In this column we present cost estimates for a variety of comprehensive parity mandates, including parity for different diagnoses, benefit provisions, and types of health insurance delivery systems. We estimated costs with an actuarial model and based our assumptions on a review of the literature and discussions with actuaries, economists, mental health researchers, employers, and representatives from managed care organizations and state mental health and substance abuse departments.

Previous estimates of costs

In 1996, four actuarial studies estimated the increase in health insurance premiums for the proposed Domenici-Wellstone parity bill. The estimates ranged from 3.2 percent by Coopers and Lybrand to 8.7 percent by Price Waterhouse. Milliman and Robertson, Inc., estimated a 3.9 percent increase in premiums and the Congressional Budget Office a 4 percent increase (2).

The differences in the estimates were largely a result of differences in the assumptions underlying the models used in the studies. The Coopers and Lybrand study, which produced the lowest estimate, assumed that 50 percent of consumers would be in a health maintenance organization (HMO) or a point-of-service (POS) plan and that both types of plans would be tightly managed. However, the literature typically classifies POS plans as moderately managed, which means that less than 30 percent—rather than 50 percent—of enrollees in 1996 would have been in a tightly managed plan (3,4).

The highest estimate, produced by Price Waterhouse, appears to have resulted from assumptions about utilization management and a shift of services from the public sector to the private sector. The model assumes that parity also applies to utilization management—specifically, that the amount of utilization management in mental health and substance abuse services for indemnity, preferred-provider organization (PPO), and POS plans would decline after parity because these plan types typically manage these types of services more aggressively than they manage medical and surgical services. None of the state or federal parity mandates require and enforce parity with respect to utilization management.

The Price Waterhouse study also assumed that after parity legislation, many mental health and substance abuse services provided in the public sector would be shifted to the private sector, thereby increasing indemnity plan mental health benefits by 50 percent and PPO and POS benefits by 21 percent. To assess the validity of this assumption, we spoke with representatives of insurance plans and mental health and substance abuse agencies in five states with parity mandates (Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Texas). None of the people we spoke with reported that their state's parity mandate resulted in a substantial shift in expenditures, clients, or services from the public to the private sector after parity. Furthermore, detailed expenditure data from New Hampshire's public mental health system show no evidence of a decline in public mental health expenditures resulting from parity. In fact, the prevailing view is that parity mandates resulted in no change in the role or activities of the public sector.

Industry experts identified two key reasons for why parity did not seem to affect public mental health and substance abuse expenditures. First, the publicly financed services are provided primarily to individuals who are not—and are not likely to become—privately insured. A large percentage of the users of publicly financed services have serious mental illness or substance use disorders, and their symptoms impair their ability to function in a work environment. Many of those who can work do so part-time and are usually not offered employer-sponsored health insurance.

Second, the public system finances many services that private insurers consider to be socially rather than medically necessary, so private insurers do not cover them and would not cover them under parity. Examples of such services are psychosocial services, such as life skills training, and services requested by a third party, such as court-ordered services.

In 1998, the parity workgroup of the National Advisory Mental Health Council (5) estimated that full parity would result in a 4 to 5 percent increase in total benefit costs for an indemnity or PPO plan, about a 3 percent increase for a POS plan, and less than a 1 percent increase for an HMO or carve-out plan. A revised model using more recent data projects a 1.4 percent overall increase in total health benefits.

In a 1997 study, Sturm (6) estimated that full parity would increase annual costs per enrollee by less than $7 under managed care. Thus, for a managed care plan with a total annual cost for mental health and substance abuse benefits of $50 per enrollee per year, the cost for these benefits would increase about 14 percent and the cost of the total health insurance premium less than 1 percent. This computation assumes that mental health and substance abuse expenses are about 5 percent of total health insurance benefits.

Methods

We used an actuarial model developed by the Hay Group, an actuarial and benefits consulting firm, to estimate health insurance premium increases for several mental health and substance abuse parity options. We estimated the costs of full and partial parity options for three diagnostic groups—all mental health and substance abuse diagnoses, mental health diagnoses only, and substance use diagnoses only—and four plan types—indemnity, PPO, POS, and HMO. We did not estimate the costs of parity for serious mental illnesses only, because data on the distribution of medical expenses for patients with serious mental illnesses were not available.

By full parity we mean that insurance benefits for the covered mental health and substance abuse diagnoses must be no less restrictive than benefits for medical and surgical diagnoses in the areas of cost sharing, service limits, and annual or lifetime limits such as lifetime benefit maximums. Partial parity means that benefits must be the same with respect to spending limits and either cost sharing or service limits. Both partial parity options comply with the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 because they require parity with respect to spending limits.

To compute the actuarial value of a benefit package, the Hay Group model relies on distributions of actual health care claims data for mental health and substance abuse services in private-sector, employer-sponsored health insurance plans. The model uses data on the distribution of mental health and substance abuse expenses for enrollees in indemnity plans and managed care plans, as well as for children and high-cost users, that is, individuals with claims of $25,000 or more in a year. For a particular benefit package, the model determines how much the health plan would pay for each patient in a distribution. The model includes assumptions about administrative costs, the level of utilization management in each plan, and patients' responses to changes in their out-of-pocket costs. The model then calculates a weighted average expense across patients.

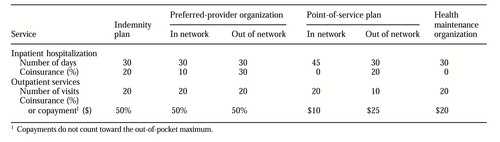

We estimated the cost of each parity benefit option by determining the difference between the estimated premium for that option and the estimated premium for a baseline plan. The new premium was the sum of the baseline premium and the increase in mental health and substance abuse expenditures caused by the increase in insurance benefits. A baseline plan is a typical health plan covering medical and surgical and mental health and substance abuse services in 1998. Our baseline benefit packages comply with the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 (Table 1).

The model assumes that all mental health and substance abuse care delivered by HMOs is tightly managed and that such management would yield relatively large savings, perhaps 30 to 40 percent. For indemnity, PPO, and POS plans, the model assumes that utilization management would lead to savings of 25 percent compared with no management. Additionally, we assumed that managing medical and surgical services would result in a 3 percent cost reduction for indemnity plans and a 5 percent reduction for PPO and POS plans (7,8).

Our assumptions about patients' responses to changes in their out-of-pocket costs were based on data from the Rand health insurance experiment (9), which found that in response to a decline in the price of health care, people in indemnity plans tended to use approximately twice as much outpatient mental health care—primarily psychotherapy—as physical health care. We assumed a slightly lower response for people enrolled in HMOs.

For PPO and POS plans, the model assumes that 70 percent of care is obtained from network providers and that the plan receives a 15 percent price discount from network providers. For POS plans, there is an additional in-network reduction of 12 percent because of denial of service by gatekeepers; out-of-network service use increases by 15 percent to partially offset this reduction.

Our assumptions about administrative costs were based on a 1994 Hay Group study for the Congressional Research Service. Administrative costs were 11 percent for indemnity, PPO, and POS plans. For HMOs, they were 15 percent for medical and surgical services and 20 percent for behavioral services.

Finally, we assumed that parity would not substantially shift the provision of mental health and substance abuse services from the public sector to the private sector.

Results

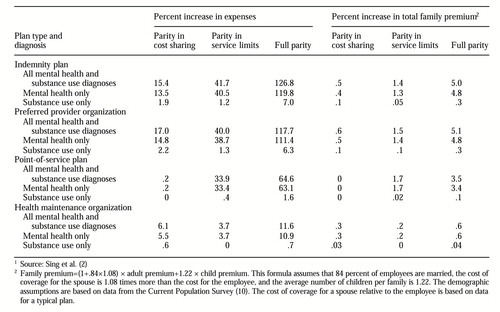

The model predicts that with full parity, PPO and indemnity plans would have the largest increases in family health insurance premiums—5.1 percent and 5 percent, respectively (Table 2), an increase in mental health and substance abuse expenditures of more than 110 percent. Premiums rise slightly more for PPOs because these expenditures take up a larger portion of the PPO premium (4.3 percent) than of the indemnity plan premium (3.9 percent). Premium increases were the lowest for HMOs, at .6 percent. The model predicts a 3.5 percent increase for POS plans.

The model predicts that full parity for mental health diagnoses only and substance abuse diagnoses only would increase premiums by 4.8 and .3 percent, respectively, for PPOs and by .6 and .04 percent, respectively, for HMOs.

The premium increases predicted by the model for the partial parity options as defined in this study were much lower. For PPOs, they are .6 percent or less if there is parity in cost sharing and 1.5 percent or less if there is parity in service limits.

Discussion

Several features of actuarial models should be taken into account in the interpretation of our predicted premium increases. First, these increases are the initial premium increases resulting from parity; they do not reflect employer responses to parity mandates. Employers could respond to an anticipated premium increase caused by a parity mandate by increasing management of mental health and substance abuse services, increasing employee contributions, dropping health insurance coverage, dropping coverage for these services, or reducing other benefits.

Second, these estimates are made with a baseline benefit package that is more generous than the one used in previous actuarial estimates of the cost of parity mandates. The baseline benefit package for each plan has a $1,000,000 lifetime spending limit for mental health services (reflecting the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996). The baseline packages for previous actuarial estimates did not reflect this act, so they have much lower lifetime spending limits, such as $50,000, for mental health and substance abuse services. If our baseline packages had a $50,000 lifetime spending limit instead of a $1,000,000 limit, our cost estimates would be roughly 15 percent higher.

Third, our study estimated premium increases for family coverage, whereas many previous studies estimated premium increases for single adults. For single adults, this model projects that full parity would raise premiums for PPOs by 4.4 percent and for HMOs by .6 percent. The family premium increase is higher than that for a single adult because the relative cost of mental health and substance abuse coverage for children in this model is higher than the relative cost of coverage for other services.

Our estimates have several implications for employers who are thinking about offering more generous mental health and substance abuse benefits. First, premium increases are much smaller if these services are tightly managed. The model predicts premium increases of less than 1 percent in a tightly managed plan, but if these services are not tightly managed after parity, the increase could be 3 to 5 percent.

Second, premium increases under the partial parity benefit options are much smaller than premium increases under the full parity benefit option. For example, premium increases for PPOs are .6 percent under parity for cost sharing and 1.5 percent for service limits, compared with 5.1 percent under full parity. Finally, once there is parity for all mental health diagnoses, the relative premium increase related to parity for all substance use diagnoses is relatively small—.3 additional percentage points for PPOs and much less for HMOs.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The authors thank Jeffrey Buck, Ph.D., Ed Hustead, B.A., Suzanne Smolkin, M.S.W., Nancy Heiser, M.A., and Myles Maxfield, Ph.D.

Dr. Sing is a senior economist at Mathematica Policy Research, 600 Maryland Avenue, S.W., Suite 550, Washington, D.C. 20024 (e-mail, [email protected]). At the time this research was conducted, Dr. Hill was affiliated with Mathematica Policy Research. He is currently a service fellow at the Center for Cost and Financing Studies of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Baseline benefits for mental health and substance abuse treatment by plan type

|

Table 2. Increases over baseline plans in mental health and substance abuse expenses and total family premiums by diagnosis and plan type1

1 Source: Sing et al(2)

1. Buck JA, Teich J, Umland B, et al: Behavioral health benefits in employer-sponsored health plans. Health Affairs 18(2):67-78, 1999Google Scholar

2. Sing M, Hill SC, Smolkin S, et al: The Costs and Effects of Parity for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Insurance Benefits. DHHS pub SMA 98-3205. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998Google Scholar

3. Jensen G, Morrison M, Gaffney S, et al: The new dominance of managed care: insurance trends in the 1990s. Health Affairs 16(1):125-136, 1997Google Scholar

4. Miller RH, Luft H: Managed care plan performance since 1980: a literature analysis. JAMA 271:1512-1519, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. National Advisory Mental Health Council: Parity in Financing Mental Health Services: Managed Care, Effects of Cost, Access and Quality. NIH pub 98-4322. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1998Google Scholar

6. Sturm R: How expensive is unlimited mental health coverage under managed care? JAMA 278:1533-1537, 1997Google Scholar

7. Khandker R, Manning W: The impact of utilization review on costs and utilization. Developments in Health Economics and Public Policy 1:47-62, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Wickizer T, Wheeler J, Feldstein P: Does utilization review reduce unnecessary hospital care and contain costs? Medical Care 27:632-647, 1989Google Scholar

9. Newhouse JP and the Insurance Experiment Group: Free for All? Lessons from the Rand Health Insurance Experiment. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1993Google Scholar

10. Health Care Benefit Value Comparison, HCBVC Version 7.6, PC Model User's Guide and Documentation. Washington, DC, Hay/Huggins Company, 1997Google Scholar