Best Practices: Best Practice for Managing Noncompliance With Psychiatric Appointments in Community-Based Care

Establishing benchmarks for compliance indicators in an individual health care system can be problematic. The literature contains many examples of assertive community treatment based on case management in public health systems (1,2). However, published data on patients' compliance with outpatient psychiatric appointments in these systems—that is, whether patients keep their appointments—are scarce. This lack of data creates some difficulty in deciding how much noncompliance should be tolerated as well as the best practices for addressing compliance problems. One might expect that assertive community treatment or assertive techniques, such as telephoned reminders about appointments from case managers, would prevent compliance problems, but that has not been our experience.

Our group reported a mean longitudinal rate of missed outpatient psychiatric appointments of 25 percent in a small sample of clients with serious and persistent mental illness in a community-based case management system (3). General rates of missed outpatient psychiatric appointments of 12 percent to 60 percent have been reported (4,5), and our rate falls near the middle (24 percent) of this range. We investigated health care expenditures, service use, and clinical indicators in the sample and found no statistical predictors of compliance with appointments and no longitudinal cost differences between patients who did and patients who did not keep their psychiatric appointments. Because hospitalization accounted for the greatest expenditure in our system, we attributed the lack of cost differences over time to the fact that no client in the sample was hospitalized during the study period.

In this column, we describe our efforts to define the best practice for managing noncompliance with psychiatric appointments in a health care system. We report the overall rate of missed appointments, describe a subsequent investigation of compliance as an indicator of quality of services, and present an intervention that was designed to improve the quality of treatment and identify the best practice for clients who do not keep their appointments.

Managing noncompliance with psychiatric appointments

Setting

Cope Behavioral Services, Inc., is a not-for-profit managed behavioral health care corporation located in Tucson, Arizona. Cope and the department of psychiatry at the University of Arizona College of Medicine forged a relationship from October 1995 to April 2001 to create an integrated service delivery system for approximately 1,500 adults with serious and persistent mental illness in Tucson's public mental health system. This program provided intensive case management services, inpatient psychiatric services, outpatient substance abuse treatment, crisis and emergency services, medication management, long- and short-term housing, individual and group psychotherapy, and social and recreational programming. All services were delivered at no charge to the client, and program costs were contained by a case rate funded by Medicaid and the state. The regional behavioral health authority that distributes all program funding in southern Arizona determined the case rate.

This integrated, flexible program assigned consumers to teams on the basis of risk factors—for example, morbidity, compliance, and the need for housing—and used consumer strengths to guide team decisions. Along with the consumer, the team included a case manager, a psychiatrist, a nurse, and other support staff. Case managers and case aides provided outreach services such as home visits, shopping assistance, and transportation to consumers as necessary. Case managers would see consumers a minimum of once a month, either in the community or in a clinical setting. As consumers required fewer interventions to achieve better functioning, the team adjusted the nature and frequency of contacts. The primary psychiatric diagnoses of the consumers in the program were mood disorders, including major depression, bipolar I disorder, and bipolar II disorder (37 percent); psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia and schizoaffective or schizophreniform disorders (37 percent); personality disorders, including types A, B, and C disorders (13 percent); and other axis I disorders (14 percent).

Four psychiatrists and one nurse practitioner provided psychiatric services. Policy dictated that clients who did not receive residential services had to go to one of three service sites to see a psychiatrist. Although psychiatrists offered a range of services, all clients who were taking medications were required to see a psychiatrist at least once every three months. Reminders in the form of visits or telephone calls from case managers were occasionally used to encourage clients to keep their psychiatric appointments.

Compliance rates

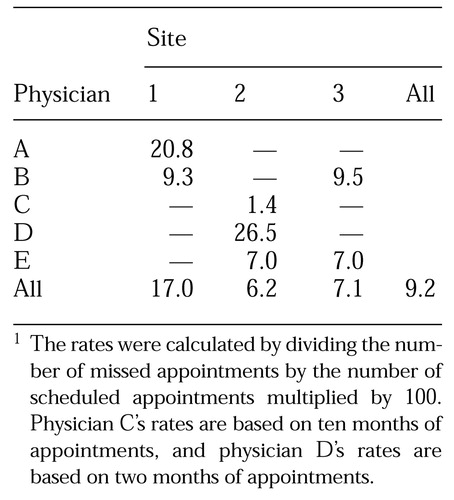

Data were collected between January 1 and December 31, 1999, for clients who failed to keep their psychiatric appointments at the three service sites. Table 1 shows the annual rates of missed appointments by service site and individual practitioner. Rates were calculated for each psychiatrist, for each site, and for the system as a whole. Data for the nurse practitioner were incomplete and are not included. One psychiatrist—physician C—worked only until October, when another psychiatrist—physician D—assumed the position.

Large individual differences in rates of missed appointments by practitioner and site are evident. The rate of noncompliance for the system as a whole was 9.2 percent. On starting his new position, physician D noticed what he interpreted to be a high rate of missed appointments and began collecting and analyzing data on clients who failed to appear for their appointments over a period of 30 days (November 7 to December 7, 1999). Of the 152 scheduled appointments during that period, 33 (22 percent) were missed. Chart reviews and follow-up reports from the case managers of these 33 clients showed that 22 (67 percent) usually kept their psychiatric appointments and had frequent contact with their case managers.

Reasons for the failure of this normally compliant group to keep their appointments ranged from transportation and scheduling problems to the fact that they did not receive a reminder telephone call. Two clients (6 percent) did not keep their appointments because they were undergoing system transfers; one client was in the process of disenrolling from the system and was no longer taking medications, and the other had requested another physician. Nine (27 percent) of the clients who did not keep their appointments had a history of missed appointments and had generally not seen a psychiatrist for more than six months. These individuals had had their medication prescriptions refilled by telephoning their case managers. For half of these clients, substance abuse problems had been documented. They were at particular risk of receiving poor-quality care and presented an unacceptable liability risk. Hence this group was targeted for an intervention.

As a result of his analysis, physician D developed and implemented the following protocol at his site. Each time a client failed to appear for a scheduled appointment, physician D reviewed the client's chart to document the date of the client's last appointment, any pattern of missed or canceled appointments, and whether medications were being provided on an ongoing basis. Each client assessment was given to the site manager for the team to review and decide whether the client was an appropriate candidate for disenrollment, a reminder from the case manager, or some other action. This case-by-case approach clarified important client issues that could be addressed at the site-management level, such as the need to telephone clients before their appointments. Clients who had not visited a psychiatrist in six months and who had received a medication refill by telephoning their case managers were targeted for treatment compliance training.

Treatment compliance training

Initially, when a client who had not visited a psychiatrist in six months telephoned for a prescription refill, only a three-day refill was given. The client was required to come to the site during the three days to make an appointment with a psychiatrist. Appointments could not be made over the telephone. After an appointment had been scheduled, the client received a medication refill that would last until the day of the scheduled appointment. After the psychiatrist had seen the client, the client received a prescription for enough medication to last until the next scheduled appointment one month later.

After the client had kept his or her appointments for six months, the training ended. A 24-hour help-on-call telephone line allowed clients who continued to miss their appointments to receive two-day prescriptions. These clients were also referred to their case managers to schedule an appointment with the psychiatrist. In addition, when a client who was undergoing treatment compliance training failed to keep an appointment, the staff met to develop a customized treatment plan for the client.

Nineteen clients were targeted for treatment compliance training. Of these, 16 responded by making and keeping scheduled appointments with the psychiatrist. In this group, three individuals required customized plans for receiving medications. In addition, we observed that five of the individuals had a greater response to treatment compliance training after an arrest that resulted in a short jail stay. The reasons for such arrests ranged from domestic violence to prostitution. Five additional clients reported that they were pleased to be singled out for the extra attention provided by the intervention. One of them was using heroin and was particularly responsive to the structure provided by the protocol.

Of the three clients who did not respond to the treatment compliance training, one went elsewhere—a Department of Veterans Affairs hospital—to receive medications when he was first asked to make an appointment with a psychiatrist. The other two could not be contacted about making a psychiatric appointment and were lost to follow-up.

The requirement that clients have face-to-face contact with the psychiatrist to receive medications may discourage medication compliance for some patients. However, our treatment compliance training data did not validate this concern. Most clients who underwent training did not have difficulty making and keeping the required appointments with the psychiatrist, and some reported enjoying the attention associated with the compliance training. The intervention provided continued access to medications via a 24-hour help-on-call number and special staffings for clients who were not immediately successful with the training procedures. These mechanisms effectively guarded against medication noncompliance.

Discussion and conclusions

As we have mentioned, it was difficult to characterize the rate of missed psychiatric appointments in this health care system because of a lack of comparable data. We have identified a benchmark of 9 percent that could be used by systems with similar characteristics. When this overall rate was stratified by site and physician, differences were apparent. Knowledge of such differences can be used to improve service delivery. The differences in rates among sites may reflect scheduling and staffing problems. The site with the highest rate of missed appointments also had the highest turnover rate of case managers during the study period, and the physician with the highest rate of missed appointments at that site also had the largest caseload. These personnel issues could have created scheduling problems that affected the rate of missed appointments.

Additionally, studies have shown that therapeutic alliance between case managers and clients is an important element in intensive case management and is associated with positive client-perceived outcome (6). Clients may fail to keep their psychiatric appointments if they feel abandoned by the loss of a case manager, overwhelmed by the task of forming a relationship with a new case manager, or simply confused by the changes that accompany the assignment of a new case manager.

Among physician D's clients who missed their appointments, the largest group consisted of those who were active in treatment and were normally compliant and who did not have a history of missed appointments. Their reasons for missing appointments were transient scheduling problems or the fact that they did not receive a reminder telephone call from the case manager. In this system, implementing the missed-appointment protocol at all sites would clarify whether site management issues need to be addressed—for example, by ensuring that clients receive reminders—or whether patterns of missed appointments indicate that an intervention such as treatment compliance training should be used. Although this training intervention was a pilot program, the initial data are promising.

One apparent benefit of the protocol we have described is that it allowed the rate of missed appointments to be defined. Differentiating between noncompliance among normally compliant clients, which can be addressed through simple reminders or scheduling changes, and noncompliance that reflects a pattern that could lead to poor-quality treatment can result in more meaningful compliance benchmarks. However, the environment for accountability and benchmarking activities in this program for clients with severe and persistent mental illness may have been unique.

The program's case rate funding created an environment for creativity in meeting challenges: the cost of service delivery had to be low to ensure that all clients received needed services, and individual staff accountability was considered an important component in cost containment. The medical director encouraged physicians to actively initiate and participate in the management of their services by regularly assessing data on hospital costs and data for individual physicians on pharmacy costs, disease severity, client encounters, and missed appointments.

The fact that physician D initiated his own assessment of missed appointments is a good example of the accountability that was fostered in this environment. In some settings, it may be difficult for physicians to exercise a positive approach to accountability in managing the care they deliver. We acknowledge that our example is simple and might seem obvious to many. Yet by taking control of compliance problems among his patients, physician D was able to achieve more effective and successful episodes of care. We believe that investigating all missed appointments so that rescheduling is timely and results in a clinic visit should be considered a best practice. Uncovering and addressing noncompliance patterns in the public sector is an important application of this practice. Analysis of rates at the system level and at the level of the individual site, physician, and consumer can lead to improvements in care.

Dr. Cruz is affiliated with the department of psychiatry in the College of Medicine at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Dr. Flaum Cruz is with Cope Behavioral Services, Inc., 101 South Stone, Tucson, Arizona 85701 (e-mail, robyncruz@dakota com.net). Dr. McEldoon is affiliated with Traditions Behavioral Health in Napa, California. William M. Glazer, M.D., is editor of this column.

|

Table 1. Percentages of missed psychiatric appointments for a managed behavioral health care organization, by physician and site, in 19991

1 The rates were calculated by dividing the number of missed appointments by the number of scheduled appointments multiplied by 100Physician C's rates are based on ten months of appointments, and physician D's rates are based on two months of appointments.

1. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:216-232, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Holloway F, Oliver N, Collins E, et al: Case management: a critical review of the literature. European Psychiatry 10:113-128, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Cruz M, Cruz RF: Compliance and costs in a case management model. Community Mental Health Journal 37:69-77, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Sparr LF, Moffitt MC, Ward MF: Missed psychiatric appointments: who returns and who stays away. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:801-805, 1993Link, Google Scholar

5. Pang A, Tso S, Ungvari G, et al: An audit of defaulters of regular psychiatric outpatient appointments in Hong Kong. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 41:103-107, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Neale MS, Rosenheck RA: Therapeutic alliance and outcome in a VA intensive case management program. Psychiatric Services 46:710-721, 1995Google Scholar