The Relationship Between Patients' Gender and Violence Leading to Staff Injuries

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Although recent research has found similar rates of violence by female and male patients who have serious mental disorders, it is less clear whether violence by female patients is as likely to result in injury as violence by male patients. This study examined the relationship between violent patients' gender and injury to staff members on an inpatient unit. METHODS: All injuries to staff caused by violent behavior by patients on a locked university-based short-term inpatient unit were identified in a search of institutional records from October 1988 to June 1999. We reviewed the medical charts of the 76 patients who injured staff members to compare their demographic and clinical characteristics with those of 314 patients hospitalized during the same period who did not injure staff. RESULTS: Nearly half of the injuries (45 percent) were caused by female patients. Moreover, the proportion of injuries caused by female and male patients was similar to the proportion of females and males in the comparison group. Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that patients' gender was not associated with injury to staff, even when the analyses controlled for other correlates of violence such as history of violence, violent thought content expressed in the admission mental status examination, and history of noncompliance with medication. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that injuries to staff members on a unit treating both men and women are as likely to be caused by violence by female patients as by male patients. When a female patient exhibits signs of an elevated risk of violence, the significance of that risk should not be discounted on the basis of her gender.

Findings from various disciplines—psychology, criminology, sociology, biology, and others—have indicated that males generally are more aggressive than females (1,2,3). However, several studies have suggested that this may not be the case with psychiatric patients (4,5,6). For example, one study found that hospitalized women patients were actually more assaultive than their male counterparts, although the men engaged in more fear-inducing behavior (4).

Another study found that staff members often underestimated the risk of violence among female patients and overestimated it among male patients (7). To account for this phenomenon, the authors suggested that staff members' vigilance and early intervention when male patients showed signs of escalating aggression may have prevented frankly assaultive behavior, and that staff members may have been less vigilant and responsive to female patients' escalating aggression. Other researchers have found that among patients who had recently been seen in a psychiatric emergency room, rates of violence were similar for men and women (6).

The few studies that have compared the severity of violence by male and female patients have yielded conflicting results (8,9), although the literature on domestic violence indicates that violence by women is less likely to result in injuries (10,11). In sum, there is evidence that female psychiatric patients may have a greater relative risk of perpetrating violence than has previously been believed, but the significance of that violence in terms of producing injuries is unclear.

The goal of this study was to examine the relationship between gender and violence by studying incidents of patient aggression severe enough to lead to injury to staff members, as opposed to threats, property damage, and milder physical aggression that did not lead to injury. We examined all incidents between October 1988 and June 1999 in which a staff member of a locked psychiatric inpatient unit was injured by a patient, and we determined the proportions of male and female patients causing the injuries. By comparing this group with another group of patients hospitalized during the same period, we evaluated whether patients' gender is associated with the risk of their injuring a staff member.

Methods

The study setting was a locked university-based short-term psychiatric inpatient unit that typically has fairly equal proportions of male and female patients. We used a retrospective design involving review of records from October 1988 to June 1999 to compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients whose violent acts caused injury to staff members with those of another group of patients seen during the same period. Injuries to staff members at our facility are officially recorded in reports filed with the hospital risk management office. We examined all injury reports during the study period and retained those in which the injury was caused by a patient's violent behavior. A total of 76 patients caused injuries over the study period.

To assess whether patients' gender was associated with their likelihood of injuring staff, we compared the group of patients who injured staff with another group of 314 patients hospitalized on the ward during the same period. The comparison group is typical of patients treated on this ward and has been described in detail elsewhere (12).

The medical record of each patient was extensively reviewed for demographic and clinical information. This information previously had been recorded on structured forms by staff in the course of providing routine clinical care, on the basis of interviews with the patient, reports from referring professionals and from family, and review of available records.

For this study, we abstracted demographic data, including gender, age, marital status, and ethnic background. We also abstracted clinical information such as ICD-9-CM diagnosis, history of substance abuse, homicidal ideation at the time of admission, history of violence, and history of compliance with treatment. We rated the most severe aggression within two weeks before hospital admission using an adaptation (13) of the rating scale developed by Lagos and colleagues (14). Patients were rated as having shown no violence; having engaged in fear-inducing behavior such as threats to attack persons, attacks on property, or verbal attacks; or having made physical attacks on persons.

Bivariate associations between gender and injury to staff were evaluated with chi square analyses, corrected for continuity, and equivalence testing (15,16). To determine whether the possible association between gender and injury to staff might be due to the differential distribution of other correlates of violence among male and female patients rather than gender per se, we also conducted correlation analyses and multivariate logistic regression analysis predicting injury to staff that included gender and other variables suggested in the literature to be linked with risk of violence.

Results

Rates of injury

Seventy-six patients who injured a staff member during the study period were identified. The injuries to staff included 34 sprains or strains (45 percent), 24 contusions or bruises (32 percent), seven abrasions or scratches (9 percent), five bites (7 percent), and two each of multiple injuries, other injuries, and pain (3 percent each). Twenty of the injuries (26 percent) led to lost work days. Forty-two of the injuries (55 percent) were caused by male patients. Forty-eight of the injured staff members (63 percent) were female. The gender of the violent patient was not significantly associated with the gender of the injured staff member or with whether the injury led to lost work days.

Characteristics of the study group

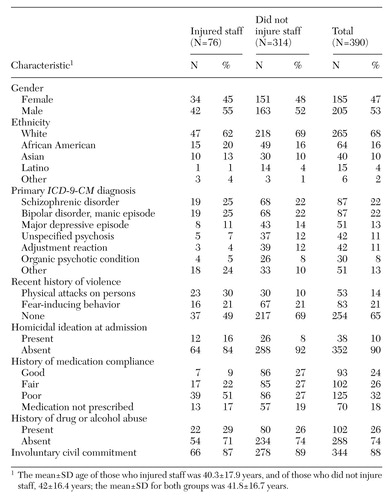

The characteristics of the patients who injured staff members and of the comparison group are summarized in Table 1. The majority of the patients in both groups were white and single, had a clinical diagnosis of a psychotic or bipolar disorder, and were hospitalized on the basis of involuntary civil commitments.

Violent patients' genderand injury to staff

Chi square analysis did not show a significant association between patients' gender and injury to hospital staff. Forty-five percent of the patients who injured staff were female (N=34), and 48 percent of the comparison group were female (N=151). Thus, proportionately, female patients and male patients caused a similar number of injuries. Moreover, equivalence testing (15,16) showed that the proportions of female and male patients in the two groups were statistically equivalent, that is, practically equal (χ2=2.705, df=1, p<.05; one-tailed test).

To place the relationship between patients' gender and causing injury to staff in context, we conducted subsidiary analyses of the relationship between causing injury to staff and demographic and clinical characteristics suggested by previous research to be relevant to the risk of violence. Kendall's tau correlations showed that patients who injured staff were significantly more likely to have a history of recent violence (τ=.20, p<.001), to exhibit homicidal ideation at the time of hospital admission (τ=.10, p<.05), and to have a history of noncompliance with psychiatric medication (τ=.14, p<.01). Injury to staff was not significantly associated with patients' age (τ=-.05), white ethnic status (τ=.06), a diagnosis of schizophrenia or mania (τ=.05), or a history of drug or alcohol abuse (τ=.03).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis

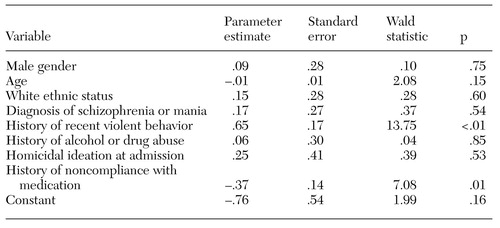

Because of the possibility that an association between patients' gender and the risk of injuring staff could have been confounded with other correlates of violence, we conducted a multivariate logistic regression analysis in which the relationship between gender and causing injury to staff was evaluated concomitantly with other demographic and clinical variables suggested by past research to be associated with risk of violence. Table 2 summarizes the model resulting from the logistic regression analysis in which injury to staff was predicted by the variables discussed in the preceding section.

The model had a substantial relationship with injury to staff (χ2= 28.67, df=8, p<.001). Clearly patients' gender still was not a predictor of causing injury to staff, even when other relevant risk factors for violence had been taken into account. In this logistic regression model, a recent history of physical assaults or fear-inducing behavior before hospital admission and a history of noncompliance with psychiatric medication predicted later injury to staff.

Discussion and conclusions

In contrast to the widely reported finding in the general literature on violence that men are much more violent than women, staff injuries in our study were perpetrated at similar rates by male and female patients. This finding is consistent with those of several recent studies that have not reported the typical preponderance of violence by males relative to violence by females in samples of persons with mental illness (4,5,6,17).

Although some research in community settings suggests that violent behavior by male patients is more severe than that by female patients, our results suggest that in the inpatient setting, females have similar rates of violence that is severe enough to cause injuries. A practical implication of this finding is that when a female inpatient exhibits signs of an elevated risk of violence, the significance of that risk should not be discounted on the basis of her gender.

Even though the outcome of interest in our study was violence by patients that caused injuries to staff members rather than a broader array of aggressive behaviors that did not result in injuries, the results of our subsidiary analyses suggest that our sample is fairly typical. Although our logistic regression analysis clearly does not represent a comprehensive model of violence, the variables we found to be most predictive of injury to staff were generally consistent with the literature on risk of violent behavior in mentally ill persons. A history of violence is typically found to be a strong predictor of future violence (18,19), as is a history of noncompliance with psychiatric medication (20). Similarly, the lack of any association between ethnic status or age and injury to staff is consistent with previous reports showing that the link between these variables and violence is attenuated in patients having acute exacerbations of mental illness (21).

Although previous research has generally found an association between acute exacerbations of schizophrenia or mania and violence (19), the lack of a relationship in this study between these variables and injury to staff is interesting. It is possible that patients who exhibit florid symptoms of these disorders and aggressive escalation receive active intervention—for example, medication, crisis intervention, seclusion, or restraint—which prevents progression to violence that injures staff.

Although the implications of our findings for assessment of the risk of violence are fairly straightforward, the results also raise the question of why male psychiatric inpatients do not cause proportionately more injuries to hospital staff, given the general tendency for males to be more aggressive than females. Future research to clarify this issue might explore several possibilities. One possibility is that clinicians fail to attend to or take seriously cues of impending violence by female patients, thereby allowing escalation to violence that causes injury. Previous studies have suggested that clinicians are less accurate in evaluating the risk of violence by female than by male psychiatric patients (7,22).

Another possible explanation for the comparable rate of injury by female and male patients is that because dangerousness is one of the factors considered in the decision to hospitalize patients, admission policies might select for female patients who are more violent than females in general (5). Finally, when patients are in acute exacerbations of major mental illness, it is possible that psychopathology attenuates their conformity to sex roles in terms of displays of aggression.

This study concerned violent behavior that was severe enough to cause injury; it did not focus on milder forms of aggression such as threats, property damage, and physical aggression that did not result in injury. The link between these milder forms of aggression and violence that produces injury remains a topic for further research.

In our study, each injury was caused by a different patient. This finding may be related to the setting of our study, a short-term inpatient unit where patients receive active treatment during civil commitment. In other settings, such as maximum-security forensic hospitals with long stays, repetitively violent patients appear to inflict a disproportionate number of injuries to staff (23).

In summary, this study suggests that among violent patients hospitalized on an acute inpatient unit, females are as likely as males to injure staff members.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by grant T32-MH-18261 from the clinical services research training program of the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Cindy Woods, M.A., Harold Baize, Ph.D., and Elizabeth Reasoner, R.N., for their assistance.

The authors are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. Send correspondence to Dr. McNiel at the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute, 401 Parnassus Avenue, San Francisco, California 94143-0984. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual convention of the American Psychological Association held August 20-24, 1999, in Boston.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of psychiatric inpatients who injured staff members and of the comparison group who did not injure staff

|

Table 2. Summary of logistic regression analysis predicting injury to staff members by 390 psychiatric patients

1. Monahan J: The Clinical Prediction of Violent Behavior. DDHS Publication ADM 89-92. Rockville, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1981Google Scholar

2. Volavka J: Neurobiology of Violence. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

3. Wilson JQ, Hernstein RJ: Crime and Human Nature, 2nd ed. New York, Simon & Schuster, 1986Google Scholar

4. Binder RL, McNiel DE: The relationship of gender to violent behavior in acutely disturbed psychiatric patients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 51:110-114, 1990Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, et al: Male-female differences in the setting and construction of violence among people with severe mental illness. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:S68-S74, 1998Google Scholar

6. Newhill CE, Mulvey EP, Lidz CW: Characteristics of violence in the community by female patients seen in a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatric Services 46:785-789, 1995Link, Google Scholar

7. McNiel DE, Binder RL: Correlates of accuracy in the assessment of psychiatric patients' risk of violence. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:901-906, 1995Link, Google Scholar

8. Larkin E, Murtagh S, Jones S: A preliminary study of violent incidents in a special hospital (Rampton). British Journal of Psychiatry 153:226-231, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Convit A, Isay D, Otis D, et al: Characteristics of repeatedly assaultive psychiatric inpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1112-1115, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Straus MA, Gelles RJ: Societal change and change in family violence from 1975-1985 as revealed by two national surveys. Journal of Marriage and the Family 48:465-480, 1986Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Morse BJ: Beyond the Conflict Tactics Scale: assessing gender differences in partner violence. Violence and Victims 10:251-272, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Beauford JE, McNiel DE, Binder RL: Utility of initial therapeutic alliance in evaluating psychiatric patients' risk of violence. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1272-1276, 1997Link, Google Scholar

13. McNiel DE, Binder RL, Greenfield TK: Predictors of violence in civilly committed acute psychiatric patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:965-970, 1988Link, Google Scholar

14. Lagos JM, Perlmutter K, Saexinger H: Fear of the mentally ill: empirical support for the common man's response. American Journal of Psychiatry 134:1134-1137, 1977Link, Google Scholar

15. Stegner BL, Bostrom AG, Greenfield TK: Equivalence testing for use in psychosocial and services research: an introduction with examples. Evaluation and Program Planning 19:193-198, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Dunnett CW, Gent M: Significance testing to establish equivalence between treatments, with special reference to data in the form of 2 x 2 tables. Biometrics 33:593-602, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Steuve A, Link BG: Gender differences in the relationship between mental illness and violence: evidence from a community-based epidemiological study in Israel. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33:S61-S67, 1998Google Scholar

18. Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Developing a clinically useful actuarial tool for assessing violence risk. British Journal of Psychiatry 176:312-319, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. McNiel DE: Correlates of violence in psychotic patients. Psychiatric Annals 27:683-690, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hiday VA, et al: Violence and severe mental illness: the effects of substance abuse and nonadherence to medication. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:226-331, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

21. Rossi AM, Jacobs M, Monteleone M, et al: Characteristics of patients who engage in assaultive or other fear-inducing behavior. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 174:154-160, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Gardner W: The accuracy of predictions of violence to others. JAMA 269:1007-1011, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Hillbrand M, Foster HG, Spitz RT: Characteristics and costs of staff injuries in a forensic hospital. Psychiatric Services 47:1123-1125, 1996Link, Google Scholar