Evaluation of a Mobile Crisis Program: Effectiveness, Efficiency, and Consumer Satisfaction

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The effectiveness and efficiency of a mobile crisis program in handling 911 calls identified as psychiatric emergencies were evaluated, and the satisfaction of consumers and police officers with the program was rated. METHODS: The study retrospectively examined differences in subjects' demographic characteristics, hospitalization and arrest rates, and costs for 73 psychiatric emergency situations handled by a mobile crisis team and 58 psychiatric emergency situations handled by regular police intervention during three months in 1995. Consumers' and police officers' satisfaction with the mobile crisis program was evaluated through Likert-type scales. RESULTS: Fifty-five percent of the emergencies handled by the mobile crisis team were managed without psychiatric hospitalization of the person in crisis, compared with 28 percent of the emergencies handled by regular police intervention, a statistically significant difference. The difference in arrest rates for persons handled by the two groups was not statistically significant. The average cost per case was 23 percent less for persons served by the mobile crisis team. Both consumers and police officers gave positive ratings to the mobile crisis program. CONCLUSIONS: Mobile crisis programs can decrease hospitalization rates for persons in crisis and can provide cost-effective psychiatric emergency services that are favorably perceived by consumers and police officers.

A national survey of mobile crisis programs conducted in 1993 showed that 39 states had such services (1). The advantages reported for such programs included improved access to treatment for mentally ill persons, the capability to avert a crisis or decrease its severity, and reduced criminalization of mentally ill persons by diverting them from jail to treatment. Mobile crisis programs are also believed to be a cost-effective service delivery strategy for reducing the costs of psychiatric hospitalization, family burden, and the costs to the criminal justice system by providing professional assessment and crisis intervention in the community (2).

The research on mobile crisis services is mostly descriptive and lacks significant empirical data on outcomes. Between 1990 and 1995 three systematic evaluations of the impact of mobile crisis services on hospitalization rates were reported. Fisher and associates (3) found no effect of the intervention on hospital admissions, but Reding and Raphelson (4) reported a significant reduction in admissions. Bengelsdorf and associates (5) provided evidence of the cost-effectiveness of mobile crisis intervention services based on diversion of patients from hospital admission to community-based services. In another study, Lamb and associates (6) concluded that mobile police- mental health outreach teams "apparently avoid criminalization of the mentally ill."

This paper reports on a retrospective study of the impact of a mobile crisis program on psychiatric hospitalization rates and arrest rates of people in crisis. Cost-effectiveness data and consumer and police satisfaction with the program are also reported.

The mobile crisis program

The mobile crisis program of DeKalb County, Georgia, is a component of the DeKalb Community Service Board, which is a comprehensive mental health service agency for the county. DeKalb County is a metropolitan community of approximately 400,000 residents and includes part of the city of Atlanta. The program was implemented in 1993 as a joint effort with the county's public safety department. Local advocacy groups and family members of mentally ill persons were actively involved in establishing the program.

The goals of the program are to provide community-based services to stabilize persons experiencing psychiatric emergencies in the least restrictive environment, to decrease arrests of mentally ill people in crisis, and to reduce police officers' time handling psychiatric emergency situations, thus freeing them to return to regular duty. The program is staffed by four police officers and two psychiatric nurses. They rotate work hours to provide a team of two officers and one nurse that operates from 3 p.m. to 10:30 p.m. seven days a week. A psychiatrist is available for telephone consultation to the team during those hours.

The team provides the initial response to 911 calls identified as psychiatric emergency situations. It responds to psychiatric emergency calls initially handled by other police units by providing telephone or radio consultation or by going to the scene and relieving the responding officers. The team also responds to referrals from the 24-hour crisis hotline of the DeKalb County community mental health center.

With police officer backup because of the high prevalence of calls involving mentally ill persons who are violent, the psychiatric nurse evaluates the person in crisis and determines whether psychiatric hospitalization is needed. If hospitalization is indicated, the team transports the person in crisis and helps with the hospital admission. If hospitalization is not needed, the psychiatric nurse provides on-site counseling and referral assistance.

When the team is not responding to emergency calls, it provides follow-up services by telephone or home visit to persons who received crisis intervention services. About 24 percent of staff time is allocated to responses to 911 calls and the rest to crisis hotline response and follow-up services.

Methods

Study sample

The study's retrospective design employed the concept of a natural experiment to address the problem of selection bias, the primary threat to validity in a nonexperimental study (7,8). Because the program's single team can provide only partial coverage of 911 calls identified as psychiatric emergencies, a comparison group of emergency 911 situations handled by regular police intervention was available. The study sample consisted of 73 psychiatric emergency cases handled by the mobile crisis team and 58 such cases handled by regular police procedures during the three-month period from October 1 to December 31, 1995.

Information was obtained from records of the public safety department and the mobile crisis program on subjects' demographic characteristics (age, race, and gender), homelessness status, whether the subject had a state psychiatric hospital admission in the previous six months, whether the crisis situation involved violence, the duration of police involvement, and the disposition for the crisis situation. Homelessness was defined as having no permanent residence and currently living on the street or in a homeless shelter.

Program measurements

Effectiveness. Program effectiveness was evaluated by measuring the differences between the hospitalization and arrest rates of the study groups.

Efficiency. According to Mayer (9), achieving efficiency may be understood as "trying to achieve the most of a desired benefit in relation to a given level of expenditure. Efficiency is a way of choosing among alternative means for achieving a standard end." For psychiatric emergencies, the standard end, or common objective, of both mobile crisis programs and regular police services is to resolve or ameliorate the situation for the immediate protection of the health and safety of the persons involved and to facilitate access to any additional treatment or follow-up services needed.

Efficiency was evaluated by comparing the cost per case (cost per episode) for mobile crisis services and regular police services. The cost per case for mobile crisis services was calculated as total program costs and any psychiatric hospitalization costs divided by the number of cases served. Program costs included the department of public safety's contribution of one police officer per team per 7.5 hour shift plus the mental health center's expenditures associated with staffing and operating the program, including administrative and support overhead costs.

Cost per case for regular police intervention included the cost of police services per hour ($39.33) multiplied by the average amount of time required per intervention (1 hour and 51 minutes) plus any psychiatric hospitalization costs. For the purposes of this study, the cost per hour of police services included average salary and benefit costs plus public safety department overhead. That overhead included administrative and supervisory costs; dispatch, training, and other support function costs; and supplies, equipment, and other operating expenses.

Cost per case of psychiatric hospitalization equaled the total cost of residential treatment services used divided by the number of cases served. The average cost per case for psychiatric hospitalization was calculated by multiplying the average length of stay by the average daily rate for facilities used by the mobile crisis team and the police. Average daily rates and lengths of stay were used to neutralize the choice of facility in comparing costs.

Consumer and police satisfaction. Consumer satisfaction was evaluated in conjunction with routine follow-up services to persons served by the mobile crisis team during the three-month study period. This convenience sample of 32 individuals or families was asked to complete the eight-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (10). Items are rated on a Likert scale of 1 to 4, with 4 indicating very satisfied and 1 very dissatisfied; possible total ratings range from 8 to 32. Consumer satisfaction was also evaluated by open-ended questions about whether needed services were received and what the consumer liked and disliked about services received.

Because the program is jointly operated by the community mental health agency and the county public safety department, police officers' satisfaction with the working relationship and the team's performance is a critical factor for the program's success. Police officers were asked to rate, on a survey designed by the author, their satisfaction with the performance of the mobile crisis team; the survey used a 5-point Likert scale, with 5 indicating very satisfied; 3, neutral; and 1, very dissatisfied. Also included were open-ended items for comments and suggestions.

The survey was distributed to officers present at each of three consecutive shift roll calls for immediate completion and return; 106 officers completed the survey.

Analysis. Chi square tests with Yates' correction for continuity and t tests with Levene's test for equality of variances were used to determine the statistical significance of differences between the two study groups. The probability level for statistical significance was set at .05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

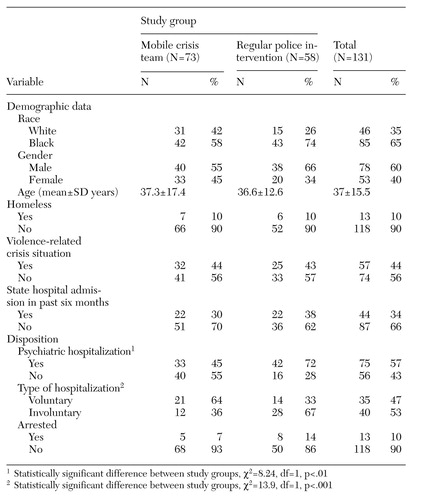

No statistically significant differences were found between the study groups in age, race, gender, or homelessness status; in whether the clients had a state psychiatric hospital admission during the previous six months; or in whether the crisis situation involved violence. Data on these and other variables are presented in Table 1.

Program effectiveness

A higher percentage of crisis situations handled by the mobile crisis team were managed without psychiatric hospitalization—55 percent, compared with 28 percent of situations handled by regular police intervention, a statistically significant difference (see Table 1). Thirty-six percent of the hospitalizations resulting from mobile crisis team interventions were involuntary, compared with 67 percent resulting from regular police interventions, also a significant difference. No statistically significant differences were found between the study groups for recent state hospital admission or arrest as a disposition of the crisis intervention.

Program efficiency

The average cost per case was $1,520 for mobile crisis program services and $1,963 for regular police intervention. Thus the average cost per case was 23 percent lower for mobile crisis services.

The average cost per case for the mobile crisis program consisted of $455 for program costs and $1,065 for psychiatric hospitalization. The average police intervention cost consisted of $73 for police services and $1,890 for psychiatric hospitalization.

The average cost of psychiatric hospitalization was higher for regular police interventions than for mobile crisis interventions. Because no statistically significant difference was found in arrest rates of persons served by the two study groups, arrest cost data were not included in the calculation of cost per case.

Consumer and police satisfaction

On the Consumer Satisfaction Questionnaire, 22 clients of the mobile crisis team gave the program a mean± SD rating of 27.4±4.9 out of a maximum possible rating of 32. Ten family members gave the program a mean rating of 27.7±5.8. According to Attkisson and Greenfield (11), the normative rating on this questionnaire by clients of community mental health agencies is 27.09±4.01.

Seventy-five percent of the 106 officers responding to the survey indicated that they were very satisfied or mostly satisfied with the performance of and working relationships with the team, 19 percent were neutral, and 6 percent were mostly dissatisfied or very dissatisfied. Responses to the open-ended questions on both surveys were predominantly positive.

Discussion

This evaluation of a mobile crisis program focused on effectiveness, efficiency, and consumer satisfaction with services provided in response to 911 calls involving psychiatric emergencies. Although savings in public mental health care costs are attributable to the program's effectiveness in preventing unnecessary psychiatric hospitalization, the goals of the agencies and advocates involved in establishing the program were more humanitarian than economic.

An anticipated benefit of the program was increased access for consumers to community-based emergency services in the least restrictive environment in order to avoid the trauma of psychiatric hospitalization whenever possible. As Bengelsdorf and associates (5) noted, the aim of an efficient crisis intervention service should not be cost containment at the expense of humane care, but should be "to titrate care so that patients receive all the care they need and no more."

This study supports beliefs about the cost-effectiveness of mobile crisis programs in reducing the use of hospitalization in managing psychiatric emergencies. Although the difference in arrest rates between the two interventions was not statistically significant, it is noteworthy that the overall arrest rate for both regular police and mobile crisis interventions was remarkably low considering the percentage of violence-related situations. This finding is consistent with that reported by Lamb and associates (6). The low overall arrest rate in the evaluation reported here is believed to be a result of the impact of the program on regular police practices, which may also account for the lack of a statistically significant difference in rates. The mobile crisis team provides telephone or radio consultation to police officers managing psychiatric crisis situations when the team is not available to provide on-site services.

Conclusions

The study suggests that mobile crisis programs can be justified as an integral component of health care systems, including managed care systems, on the basis of cost-effectiveness. Although more rigorous evaluation of the costs and benefits of mobile crisis services is needed, the positive responses of consumers and police officers to the service described here indicate the perceived benefit of such services.

Mr. Scott is director of care management at Georgia Mountains Community Services, P.O. Box 907891, Gainesville, Georgia 30501. When this paper was written, he was affiliated with the DeKalb Community Service Board in Decatur, Georgia.

|

Table 1. Client characteristics and disposition for psychiatric emergencies handled by a mobile crisis team and by regular police intervention

1. Geller JL, Fisher WH, McDermeit M: A national survey of mobile crisis services and their evaluation. Psychiatric Services 46:893-897, 1995Link, Google Scholar

2. Zealberg JJ, Santos AB, Fisher RK: Benefits of mobile crisis programs. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:16-17, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Fisher WH, Geller JL, Wirth-Cauchon J: Empirically assessing the impact of mobile crisis capacity on state hospital admissions. Community Mental Health Journal 26:245-253, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Reding GR, Raphelson M: Around-the-clock mobile psychiatric crisis intervention: another effective alternative to psychiatric hospitalization. Community Mental Health Journal 31:179-187, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bengelsdorf H, Church JO, Kaye RA, et al: The cost-effectiveness of crisis intervention: admission diversion savings can offset the high cost of service. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:757-762, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Lamb HR, Shaner R, Elliott DM, et al: Outcome for psychiatric emergency patients seen by an outreach police-mental health team. Psychiatric Services 46:1267-1271, 1995Link, Google Scholar

7. Moffitt R: Program evaluation with nonexperimental data. Evaluation Review 15:291-314, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Rossi PH, Freeman HE: Evaluation: A Systematic Approach. Beverly Hills, Calif, Sage, 1992Google Scholar

9. Mayer R: Policy and Program Planning: A Developmental Perspective. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1985Google Scholar

10. Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, et al: Assessment and refinement of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Evaluation and Program Planning 2:197-207, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Attkisson CC, Greenfield TK: Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 and Service Satisfaction Scale-30, in The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment. Edited by Maruish ME. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1994Google Scholar