State Health Care Reform: The Effects of Program Realignment on Severely Mentally Ill Persons in California's Community-Based Mental Health System

On July 1, 1991, the California legislature enacted a plan, called "Program Realignment," to decentralize the state mental health system. The program gave local mental health authorities significantly greater autonomy in the provision of services (1,2). It allowed local governments to remove most categorical programs that restrict the use of funding, to transfer monies between trust funds, and to roll over revenues from one fiscal year to the next. Funds that previously covered the state hospital bed allocation as a fixed asset were allocated directly to local governments. Previous funding sources for county-based mental health services were consolidated into a single source—a dedicated sales tax that was redistributed to equalize funding levels among counties.

This significant change in the financing structure provided both incentives and risks to local mental health authorities. Local governments were charged with full responsibility for providing mental health services that could either surpass the limited annual budget or generate savings through cost-effective management (3).

For the first time in California, the severely mentally ill population was specified as the target population. The legislation states, "Persons with serious mental illness have severe, disabling conditions that require treatment" and should be given "a high priority for receiving available services" (4). However, the legislation did not provide specific incentives for giving them service priority.

The study reported here examined how access to, utilization of, and cost of community-based mental health services changed during the realignment period in relation to patients' needs. Our main concern was with the severely mentally ill population. These individuals are highly vulnerable, and their lives can be in danger if they do not receive appropriate care. On the basis of previous findings (5), we assumed that different psychiatric diagnoses are associated with different levels of severity and, therefore, with different levels of need. We examined three questions: how admission rates for various mental disorders differed before and after the realignment, how utilization levels of mental health services changed over the realignment period in each diagnostic category, and how the costs of mental health services were reduced for each diagnosis over the realignment period.

Methods

Data from California's Client Data System (CDS) were obtained for a six-year period, for fiscal years 1988 to 1990 and 1992 to 1994. The CDS contains extensive information on a quarter-million individuals who received public mental health services in California annually. A sample of 75,791 patients, representing 5 percent of the patient population for each of the six years, was randomly selected.

The study's dependent variables included psychiatric diagnosis, utilization level, and estimated cost of the services provided. Psychiatric diagnosis was the principal diagnosis at admission, assessed by DSM-III-R criteria. Diagnoses included schizophrenia, mood disorders, other psychotic disorders, organic mental disorders, substance use disorders, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and adjustment disorder. The utilization level was the amount of treatment, which was measured by units. Each unit represented a 24-hour period in a 24-hour-care setting—that is, inpatient care—or a client contact with mental health professionals or facilities for outpatient services. Service cost was the gross treatment cost estimated by providers. The independent variable, time, was coded as a dummy variable, with 0 indicating the prerealignment period and 1 indicating the postrealignment period.

A variety of demographic variables, including age, gender, ethnicity, education, and employment status, were used as covariates. The level of functional impairment is an additive predictor of need (6) and therefore was controlled in the analysis as a covariate because an artificial cutoff on this score was not meaningful in categorizing the level of need.

Logistic regression analysis was conducted to study changes in the rates of psychiatric diagnoses over the realignment period for inpatient treatment, outpatient services, and both types of services. Each of the eight psychiatric diagnoses was used as a dependent variable, and time, indicating the pre- and postrealignment periods, was used as the independent variable.

Using a general linear model, analysis of variance was conducted to compare differences in utilization and costs for each psychiatric diagnosis between the pre- and the postrealignment periods. Least-squares means were computed to compare the differences over time with adjustment for covariate variables.

Results

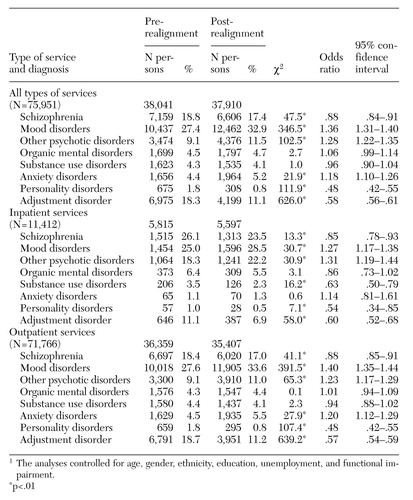

Table 1 shows the differences in psychiatric diagnoses between the pre- and postrealignment periods for inpatient care, outpatient care, and all types of services. Over the realignment period, for patients receiving inpatient care, diagnoses of mood disorders and other psychotic disorders increased by a factor of 1.3 (p≤.01), while diagnoses of schizophrenia, substance use disorders, personality disorders, and adjustment disorder decreased significantly (p≤.01). For patients receiving outpatient services, diagnoses of mood disorders, other psychotic disorders, and anxiety disorders increased significantly by either 1.4 times or 1.2 times (p≤.01). Diagnoses of schizophrenia were reduced to 88 percent of the prerealignment level, personality disorders were reduced to 48 percent of that level, and adjustment disorders were reduced to 57 percent of that level (p≤.01). The results were the same when all types of services were considered.

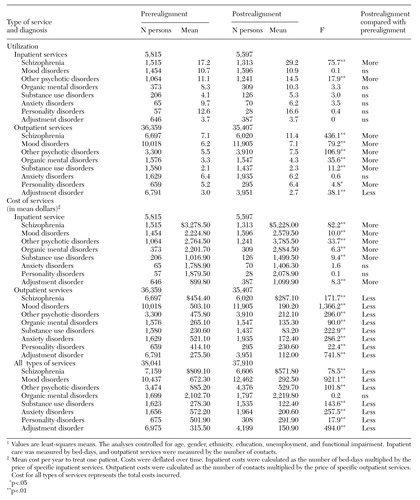

Table 2 shows differences in utilization between the two periods. After the realignment, patients with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders received significantly more inpatient treatment (p≤.01). Patients with schizophrenia, mood disorders, other psychotic disorders, organic mental disorders, substance use disorders, and personality disorders received significantly more outpatient treatment (p≤.01), while patients with adjustment disorder received significantly less treatment in the outpatient setting (p≤.01).

Table 2 also shows differences in costs of treatment over the two periods. After the realignment, inpatient treatment costs were significantly higher for patients with schizophrenia, mood disorders, other psychotic disorders, organic mental disorders, substance use disorders, and adjustment disorder (p≤.01). However, treatment costs for all psychiatric diagnoses were significantly lower for outpatient services after the realignment (p≤.01). When all types of services were examined, treatment costs for all psychiatric diagnoses except organic mental disorders were significantly lower after the realignment.

Discussion

After implementation of the realignment of the community-based mental health service system in California, admission rates for all types of services increased significantly for patients with more severe diagnoses and fell significantly for those with mild diagnoses. Clearly, regardless of the type of services, patients with severe mental disorders were more likely to be admitted to treatment after the realignment, and patients with mild mental disorders were less likely. Patients with schizophrenia were the exception. Their admission rate fell significantly across all service types.

Conceivably, the decreased rate of diagnoses of schizophrenia may reflect a recent change in diagnostic trends. Diagnostic screening for schizophrenia might also be more rigorous when the mental health system monitors it more closely because of financial considerations. However, the sharp contrast between the increase in diagnoses of more severe mental disorders and the decrease in diagnoses of mild mental disorders cannot be fully explained by diagnostic modifications. Probably the mental health system was realigned to take in more persons with severe mental illness or to take in fewer persons with less severe illness.

A deliberate effort to alter admission rates to services for patients with various diagnoses can also be seen in the context of treatment type. The findings indicated that after the realignment the rate of substance use disorders was significantly reduced in the inpatient setting and the rate of anxiety disorders was significantly increased in the outpatient setting.

It has long been argued that substance use disorders can be treated more efficiently in settings other than the inpatient setting (7,8) and that patients with anxiety disorders can obtain adequate treatment at lower cost in outpatient services. Thus a drop in inpatient treatment of substance use disorders and an increase in outpatient treatment of anxiety disorders might have occurred as a result of efforts to reduce costs under the realignment.

After the realignment, the amount of inpatient treatment provided was significantly higher for patients with severe diagnoses—that is, schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. The amount of outpatient treatment increased for most diagnoses.

During the realignment, nearly 1 percent of severely mentally ill patients were shifted from state hospitals to community-based services. Thus the results might reflect an increased level of need among inpatients. The level of need for outpatients with schizophrenia, substance use disorders, and personality disorders also may have increased during the realignment, because these persons might have been shifted from inpatient care to outpatient services. For outpatients with mood disorders, other psychiatric disorders, and organic mental disorders, the increased utilization of outpatient services indicated an increased attention to severe mental disorders. Overall, after the realignment, the level of utilization of inpatient care was not cut as severely as one might expect. The amount of outpatient services was increased for patients with severe diagnoses and met the level of needs for patients with most mild diagnoses.

After the realignment, the treatment cost per inpatient was significantly higher, and the level of inpatient utilization stayed the same for most diagnoses, suggesting that inpatients continued to receive expensive services when it was necessary. However, outpatient costs per user were significantly lower for all diagnoses, despite an increased utilization level for patients with most diagnoses. The results suggest that the cost of outpatient services was significantly lower in the postrealignment period as a result of service contracting prompted by the realignment program. When both inpatient and outpatient services were considered, treatment cost per user was significantly lower in the postrealignment period for all diagnoses except organic mental disorders, implying that savings were achieved mainly through decreases in the costs of outpatient services.

Conclusions

After the implementation of the State-Local Program Realignment Act in California, patients who needed services the most seemed to be least adversely affected. For patients with more severe psychiatric diagnoses, access to the mental health system was actually enhanced. These patients were more likely to be admitted for treatment of all types, particularly inpatient care. After the realignment, patients with more severe diagnoses received an equal or greater amount of inpatient treatment or a greater amount of outpatient treatment.

For patients with less severe diagnoses, the results were mixed. After the realignment, they were less likely to be admitted for treatment of any type, or, if they were sick enough to be treated, they received the same amount of inpatient treatment or a greater amount of outpatient treatment. The level of treatment could be decreased if the severity of patients' illness increased.

Overall, under the financial constraints imposed by the realignment, patients' needs for services were met in order of severity of mental illness. The most severely mentally ill persons received the highest priority for mental health services.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant P50-MH-43694 from the National Institute of Mental Health and grant T32-HS00026-10 from the Agency for Health Care Policy Research.

Dr. Zhang is senior research associate in the department of medicine in the School of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University (W-G37), 10900 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, Ohio 44106-4961 (e-mail [email protected]). Dr. Scheffler is distinguished professor of health economics and public policy in the department of health policy and research in the School of Public Health at the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Snowdenis professor of social welfare in the School of Social Welfare and director of the Center for Mental Health Services Research at the University of California, Berkeley. Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., and Colette Croze, M.S.W.,are editors of this column.

|

Table 1. Differences in the number of persons with eight psychiatric diagnoses receiving public mental health services in California before and after realignment of the community-based mental health system1

1 The analyses controlled for age, gender, ethnicity, education, unemployment, and functional impairment

|

Table 2. Differences in the utilization and costs of services for persons with eight psychiatric diagnoses receiving public mental health services in California before and after realignment of the community-based mental health system1

1 Values are least-squares meansThe analyses controlled for age, gender, ethnicity, education, unemployment, and functional impairment. Inpatient care was measured by bed-days, and outpatient services were measured by the nnumber of contacts.

1. Scheffler R, Wallace N, Hu T-W, et al: The effects of decentralization on mental health service costs in California. Mental Health Research Review 5:31-32, 1998Google Scholar

2. Scheffler RM, Wallace NT, Hu T-W, et al: The impact of risk shifting and contracting on mental health service costs in California. Inquiry 2000 37:121-133, 2000Google Scholar

3. Masland MC: Local Variation in Response to Decentralization of Authority in California's Public Mental Health System. Doctoral dissertation, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, 1997Google Scholar

4. West's Annotated California Codes: Welfare and Institutions Code. St Paul, Minn, West, 1998Google Scholar

5. Landerman LR, Burns BJ, Swartz MS, et al: The relationship between insurance coverage and psychiatric disorder in predicting use of mental health services. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:1785-1790, 1994Link, Google Scholar

6. Katz S, Kessler RC, Frank RG, et al: The use of outpatient mental health services in the United Stated and Ontario: the impact of mental health morbidity and perceived need for care. American Journal of Public Health 87:1136-1143, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Shwartz M, Baker G, Mulvey KP, et al: Improving publicly funded substance abuse treatment: the value of case management. American Journal of Public Health 87:1659-1664, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Austin CD, McClelland RW: Case management in the human services: reflections of public policy. Journal of Case Management 6(3):119-126, 1997Google Scholar