Mental Health Team Leadership and Consumers' Satisfaction and Quality of Life

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to determine the association between leadership styles of leaders of mental health treatment teams and consumers' ratings of satisfaction with the program and their quality of life. METHODS: A multifactor model has distinguished three factors relevant to leadership of mental health teams: transformational leadership, in which a leader's primary goal is to lead the team to evolving better programs; transactional leadership, in which the leader strives to maintain effective programs through feedback and reinforcement; and laissez-faire leadership, an ineffective, hands-off leadership style. Research has shown transformational leadership to be positively associated with measures of the team's functioning, but the effects of leadership style on consumers is not well known. A total of 143 leaders and 473 subordinates from 31 clinical teams rated the leadership style of the team leader. In addition, 184 consumers served by these teams rated their satisfaction with the treatment program and their quality of life. RESULTS: Consumers' satisfaction and quality of life were inversely associated with laissez-faire approaches to leadership and positively associated with both transformational and transactional leadership. Moreover, leaders' and subordinates' ratings of team leadership accounted for independent variance in satisfaction ratings—up to 40 percent of the total variance. CONCLUSIONS: Leadership seems to be an important variable for understanding a team's impact on its consumers.

Mental health and psychiatric rehabilitation programs can have a significant impact on the lives of persons with severe and persistent mental illness (1,2,3). These programs rely on interdisciplinary teams to provide services. Teams that work well together provide more satisfactory services to their clientele (4,5).

To understand what elements of effective teamwork are relevant to services, researchers have examined relationships among a variety of staff variables and consumers' functioning, especially aggression. Results suggest that consumers' hostility is associated with staff members who make critical statements (6), have poorly defined roles (7), and fail to be optimistic about innovative approaches to treatment (8).

Effective leaders are essential for team members to function competently (9); unfortunately, relatively little research has examined the relationship between team leadership and staff performance on mental health teams. Organizational psychologists have studied a variety of models for understanding leadership that are relevant to this question. One particularly useful theory to arise out of this research is the multifactor model of leadership developed by Bass and colleagues (10,11,12,13,14), which distinguishes two sets of important skills. Leaders who demonstrate transformational leadership skills help team members transform programs to meet the ever-evolving needs of their clientele. Those with transactional leadership skills attend to the day-to-day tasks of the team that need to be completed to operate the program smoothly. Transformational goals are achieved through charisma, inspiration, intellectual stimulation, and consideration of the interests of individual staff members. Transactional goals are pursued using the strategies of goal setting, feedback, self-monitoring, and reinforcement.

These effective styles have been contrasted to what has been shown to be a fundamentally ineffective approach to leadership—laissez-faire leadership. The laissez-faire leader is aloof, uninvolved, and disinterested in the day-to-day activities of the treatment team.

The multifactor model was originally developed in business and military settings. Two subsequent studies, involving more than 1,000 staff working in human service settings, showed that independent groups of mental health staff (15) and rehabilitation staff (16) identified leadership factors that paralleled the transformational and transactional leadership distinction. A third study showed that transformational leadership was positively associated with the organization's culture and negatively associated with staff burnout on mental health teams (Corrigan PW, Lickey SE, Campion J, et al, unpublished data, 1999). Unfortunately, the positive impact of staff members' leadership on consumers is not well known. One of the few studies in the literature suggested that mental health teams under strong managerial control serve consumers who report greater alienation from the staff (17). Positive effects of leadership on consumers' satisfaction are not well documented.

The purpose of the study reported here was to determine the relationship between transformational and transactional styles and consumers' perspectives on their mental health programs. One way to measure the consumer's perspective is by assessing satisfaction with the clinical program. Consumers' satisfaction has been shown to be associated with positive perceptions about staff (18), perseverance in treatment (19), and self-reported treatment gains (20,21). An indirect way to assess consumers' functioning is by evaluating their quality of life. People benefiting from psychosocial treatment programs report a higher quality of life (22,23). Moreover, consumers reporting higher treatment satisfaction tend to report a better quality of life (24).

Earlier research suggests that cohesive teams with well-defined roles lead to less hostile and more therapeutic programs (4,6,25). Consequently, we expected that ratings of satisfaction and quality of life would be positively associated with active forms of leadership like transformational and transactional leadership; we expected laissez-faire leadership to be negatively associated with consumers' satisfaction and quality of life.

A leader's style also depends on the eye of the beholder; leaders' perceptions of their leadership style may differ from those of their subordinates. Hence, in this study, we contrasted leaders' and subordinates' perceptions of leadership style and their association with consumers' satisfaction and quality of life.

Methods

As part of a large, multiyear investigation of factors that enhance leadership, 68 teams providing services to persons with severe and persistent mental illness participated in the Midwest mental health team leadership study. At the time the data were gathered (January 1996 to July 1997), these teams included more than 200 leaders and 600 subordinates serving consumers. The teams worked in state hospitals and community mental health programs, providing psychopharmacological and psychosocial treatments for adults with serious and persistent mental illness. Teams ranged in size from nine to 41 members. Community-based teams provided skills training, supported employment services, assertive community treatment, and drop-in services.

Data were collected from three levels of participants: team leaders, who provided perceptions of their leadership style; subordinates, who rated their leader; and consumers, who reported their satisfaction with services and quality of life. Team leaders were defined as individuals who have direct responsibility and who supervise a group of staff that provides clinical or rehabilitation services to persons with severe mental illness. This definition excludes central administrators and persons who lead ancillary services.

Data from consumers

Teams were asked to select at random three to five current consumers in the program to provide information about their satisfaction with the program and their quality of life; 184 consumers agreed. Consumers were administered the 42-item Patient Satisfaction Scale (PSS) (26). Previous research suggests that consumers' feedback on satisfaction with treatment is frequently confounded by a halo effect ("I liked all of the treatment") or a devil effect ("I liked none of the treatment") (27). To minimize these effects, consumers were instructed to rate PSS items by comparing their current treatment program to a program in which they had previously participated, using a 7-point, better-than-worse-than scale, with 7 indicating the best treatment ever, 6 indicating that their current treatment was much better than the other treatment, and so forth. Ratings on the scale are summed into an overall satisfaction score, with higher scores indicating more satisfaction with treatment. Previous research has shown the overall score to have satisfactory reliability, construct validity, and sensitivity to the effects of program change (26,28).

Of the various measures of quality of life, the subjective component of Lehman's Quality of Life Interview (QOLI) (22) was selected for the study because it has been tested and replicated with the largest sample of persons with severe mental illness. The measure comprises 17 items about domains of independent living to which subjects respond on a 7-point scale, with 7 indicating delighted and 1 indicating terrible. An overall quality-of-life index is determined by summing the 17 items; higher scores represent better quality of life. The QOLI has been shown to have satisfactory parallel-form reliability, internal consistency, and difference-score reliability (29,30). Moreover, when the QOLI was used with three independent research samples, the QOLI index of subjective quality of life was shown to correlate with objective quality of life (30).

Data from leaders and subordinates

Leaders and subordinates completed the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) (31). Leaders were instructed to rate 44 items representing leadership skills according to "how you think your subordinates view you" (31). Subordinates were instructed to judge individual items in terms of "how frequently it fits your supervisor." Items are rated on a 5-point frequency scale, with 1 indicating frequently if not always and 5 indicating not at all; lower scores represent greater endorsement of a scale's construct. The MLQ has been widely investigated and shown to have excellent internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and construct validity (31).

Results of factor analyses have shown that the MLQ yields eight reliable factors. Transformational leadership is represented by four factor scales: charisma, inspiration, intellectual stimulation, and consideration of the interests of individual staff members. Three scales represent transactional leadership: contingent reward, active management-by-exception, and passive management-by-exception. Leaders who use contingent reward regularly reinforce staff for accomplishing job goals. In active management-by-exception, leaders are vigilant for errors and ready to provide guidance. In passive management-by-exception, leaders provide feedback only when differences from the standard are blatantly manifest. Higher summed scores on the relevant factors indicate less endorsement of transformational and transactional leadership styles. The final factor, nonleadership, is called laissez-faire. High scores on this factor represent less laissez-faire leadership.

Data analyses

Most teams in this study had more than one leader who worked closely with the team. Moreover, team members closely interacted, and they had a collaborative impact on consumers. Hence, the relationship between leader, subordinate, and consumer is not well construed as unidirectional or one-to-one. As a result, the unit of analysis for this study was the team and not the individual, a strategy consistent with organizational research on leadership (32). Mean scores for leaders, subordinates, and consumers for each dependent variable were determined for each team. Individual teams were included in the study only if data were provided by leaders, subordinates, and consumers. Thirty-one of the 68 teams met this criterion. These teams consisted of 143 leaders, 473 subordinates, and 184 consumers.

Differences between leaders and subordinates were determined using paired t tests. Pearson product-moment correlations were used to examine associations between leaders' and subordinates' ratings of leadership and consumers' ratings of satisfaction and quality of life. To determine whether leaders' and subordinates' ratings independently accounted for variance in consumers' ratings, a stepwise multiple regression was conducted.

Results

Most teams had more than one leader; leaders commonly included a lead psychiatrist, charge nurse, and a clinical manager. The mean±SD age of the leader sample was 47.9±5.1 years. Of the 143 leaders, 101 (70.7 percent) were women. A total of 117 leaders (81.8 percent) were European American and 26 (18.2 percent) were from other groups, including African American, Latino, and Asian American. They had diverse educational backgrounds: 12 leaders (8.4 percent) had completed high school, 25 (17.5 percent) had completed some college, 30 (21 percent) had an associate's degree, 31 (21.7 percent) had a bachelor's degree, 27 (18.9 percent) had a master's degree, and 18 (12.6 percent) had a doctoral degree. Leaders worked a mean±SD of 13± 5.9 years in the field.

Consumers' satisfaction and quality-of-life ratings were not significantly correlated with demographic characteristics of leaders.

The mean±SD age of the 473 subordinates was 42.5±7.4 years, and 338 (71.4) were women. This group was not significantly different from the group of leaders in age or gender, nor did they differ significantly from the leaders in ethnic backgrounds. A total of 391 subordinates (82.7 percent) were European American, and 82 (17.3 percent) were from the other groups listed above. Overall educational levels were significantly lower among subordinates than among leaders (p<.001). A total of 110 (23.3 percent) had completed high school, 148 (31.3 percent) had completed some college, 69 (14.6 percent) had an associate's degree, 60 (12.7 percent) had a bachelor's degree, 74 (15.6 percent) had a master's degree, and 12 (2.5 percent) had a doctoral degree.

Subordinates also worked in the field for a significantly shorter period of time than leaders. A total of 315 of the subordinates (66.6 percent) were nurses, technicians, or aides; 148 (31.3 percent) were psychologists or social workers; and ten (2.1 percent) were in a category "other."

Two demographic characteristics of subordinates were found to correlate significantly with consumers' satisfaction; subordinates' age was inversely related to satisfaction (r=−.32, p<.05), and their education level was positively associated with consumers' satisfaction (r=.34, p<.05).

Leadership and consumers' satisfaction

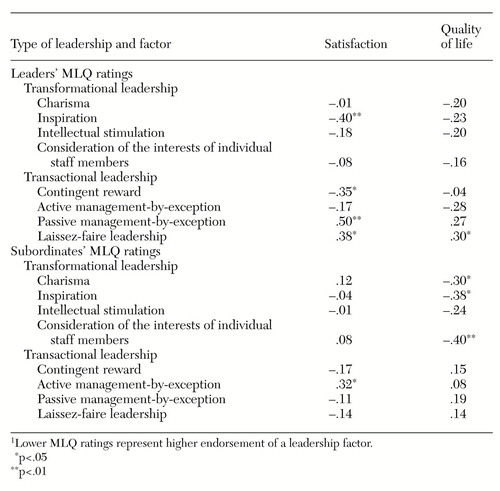

Pearson product-moment correlations representing associations between leaders' and subordinates' ratings of leadership and consumers' ratings of program satisfaction are summarized in Table 1. The total consumer satisfaction score was significantly associated with four MLQ ratings provided by leaders. Leaders who rated themselves as high in inspiration worked in programs with consumers who reported high satisfaction. Moreover, leaders who ranked themselves as low in passive management-by-exception and laissez-faire leadership worked in programs with high consumer satisfaction. Finally, leaders who were more frequent users of contingent rewards with their staff worked in programs with high consumer satisfaction.

Correlations between subordinates' MLQ ratings and consumers' ratings of satisfaction were different. Subordinates who ranked their leaders as high on active management-by-exception worked in programs where consumers reported low satisfaction.

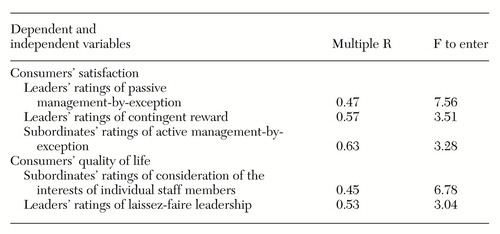

A stepwise multiple regression was conducted to determine whether leaders' and subordinates' ratings independently accounted for variance in data on consumers' satisfaction. Results are summarized in Table 2. Note that leaders' and subordinates' MLQ ratings accounted for independent variance in consumers' satisfaction scores. In particular, scores that represented transactional leadership—leaders' ratings of passive management-by-exception and leaders' ratings of contingent reward—were first entered into the equation. In addition, subordinates' ratings of active management-by-exception accounted for independent variance in satisfaction. The three scales together accounted for about 40 percent of the variance in satisfaction.

Leadership and quality of life

Table 1 also presents Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients representing the association between leaders' and subordinates' ratings of leadership and consumers' ratings of quality of life. Three subordinates' ratings were significantly associated with consumers' quality of life. Subordinates who viewed their leaders as charismatic, inspiring, and considerate of the interests of individual staff members were more likely to work in programs that had consumers with higher quality of life. Although leaders' ratings did not correlate significantly with consumers' quality-of-life scores, the relationship between leaders' ratings of laissez-faire leadership and quality of life showed nonsignificant trends (p<.10).

Another stepwise regression was completed to determine whether subordinates' ratings accounted for independent variance in quality of life. These results are also summarized in Table 2. Both leaders' and subordinates' ratings accounted for independent variance in consumers' quality of life. In particular, subordinates' ratings of leaders' consideration of the interests of individual staff members and leaders' ratings of laissez-faire leadership were associated with quality of life, accounting for 28 percent of the variance.

Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between leadership of treatment teams and consumers' reports of satisfaction with care and quality of life. One finding from this study was the negative influence of laissez-faire leadership. Consumers in programs led by leaders who rated themselves as laissez-faire reported lower satisfaction and diminished quality of life. Moreover, leaders who rated themselves as using passive management-by-exception worked in programs with consumers who reported less satisfaction.

Passive management-by-exception is closely related to laissez-faire leadership; in both, leaders assume a hands-off, distant approach to staff, responding only when significant problems require it. Earlier research showed that poor leadership, which was characterized as laissez-faire and as using passive management-by-exception, resulted in greater burnout and less cohesion among staff (Corrigan PW, Lickey SE, Campion J, et al, unpublished data, 1999). This lack of guidance and structure seems to trickle down to consumers.

Results of this study also suggest that transformational leadership is related to benefits for consumers. Leaders who saw themselves as inspirational were more likely to work in programs that consumers found satisfying. Moreover, subordinates who viewed their leaders as charismatic, inspirational, and considerate of individuals worked in programs with consumers who reported a relatively higher quality of life.

Findings from the multiple regression analysis suggested that the association between leadership and consumers' satisfaction was multidetermined. Leadership as rated by leaders and by subordinates accounted for separate variance in consumers' satisfaction. Perhaps leaders have a direct effect on the program as well as an indirect effect on their team, who also have an impact on the program. Moreover, results suggested that the presence of transactional leadership and the absence of laissez-faire approaches accounted for independent variance. These divergent paths need to be examined in future studies.

In addition, the direction of associations should be determined. It is unclear from these findings whether transformational leadership leads to consumers' satisfaction and better quality of life. Moreover, despite these significant findings, leadership variables accounted for only 40 percent of the variance in consumers' satisfaction and quality of life. Future research must examine what additional team variables, such as the treatment culture and staff burnout, may interact with leadership or account for independent variance in these consumer variables.

Another disconcerting finding was the difference in correlation matrices between consumers' ratings and the ratings of leadership by leaders and by team members. In some ways, the differences make sense. Bass and Avolio (33) have discussed how perceptions of leadership vary among perceivers. Unfortunately, one reason we designed the study to include both leaders' and subordinates' leadership ratings was to cross-validate associations between leaders' and consumers' ratings. However, the study did not find any significant associations between leaders' ratings and consumers' ratings. Future research should identify constructs that mediate the effects on consumers' ratings of subordinates' versus leaders' perceptions.

Results from this study, if supported, have implications for training leaders. Active leadership skills that inspire and intellectually stimulate appear to be an important element in programs that are satisfactory to consumers. Research suggests that these skills can be learned by team leaders and that leaders with these skills can have significant effects on line-level staff charged with providing quality services to consumers (34).

Acknowledgment

This project was made possible in part by grant H263A50006 from the U.S. Department of Education.

The authors are affiliated with the University of Chicago Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 7230 Arbor Drive, Tinley Park, Illinois 60477 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Pearson product-moment correlations between team leaders' and subordinates' ratings of leadership on the Multifactor Leadership Questionaire (MLQ)1 and consumers' ratings of satisfaction with their quality of life

|

Table 2. Results of a multiple regression of selected ratings by leaders and subordinates using the Multifactor Leadership Questionaire and consumers' ratings of satisfaction with the program and their quality

1. Bachrach LL: Psychosocial rehabilitation and psychiatry in the care of long-term patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1455-1463, 1992Link, Google Scholar

2. An Introduction to Psychiatric Rehabilitation. Columbia, Md, International Association of Psychosocial Rehabilitation Services, 1994Google Scholar

3. Liberman RP (ed): Effective Psychiatric Rehabilitation. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 53, 1992Google Scholar

4. Corrigan PW, McCracken SG: Psychiatric rehabilitation and staff development: educational and organizational models. Clinical Psychology Review 15:699-719, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Yank GR, Barber JW, Hargrove DS, et al: The mental health treatment team as a work group: team dynamics and the role of the leader. Psychiatry: Journal for the Study of Interpersonal Processes 55:250-264, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Moore E, Ball RA, Kuipers L: Expressed emotion in staff working with the long-term adult mentally ill. British Journal of Psychiatry 161:802-808, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Katz P, Kirkland FR: Violence and social structure on mental hospital wards. Psychiatry 53:262-277, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Corrigan PW, Holmes EH, Luchins D, et al: The effects of interactive staff training on staff programming and patient aggression in a psychiatric inpatient unit. Behavioral Interventions 10:17-32, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Sluyter GV: Mental health leadership training: a survey of state directors. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:201-204, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Bass BM: Leadership: good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics 13:26-40, 1985Crossref, Google Scholar

11. Bass BM: Bass & Stogdill's Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Managerial Applications, 3rd ed. New York, Free Press, 1990Google Scholar

12. Bass BM, Yammarino FJ: Congruence of self and others: leadership ratings of naval officers for understanding successful performance. Applied Psychology: An International Review 40:437-454, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Hater JJ, Bass BM: Superiors' evaluations and subordinates' perceptions of transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology 73:695-702, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Yammarino FJ, Bass BM: Transformational leadership and multiple levels of analysis. Human Relations 43:975-995, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Corrigan PW, Garman AN, Lam C, et al: What mental health teams want in their leaders. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 26:111-124, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Corrigan PW, Garman AN, Canar J, et al: Characteristics of rehabilitation team leaders: a replication. Rehabilitation Counseling Bulletin 42:186-195, 1999Google Scholar

17. Kyrouz EM, Humphreys K: Do health care workplaces affect treatment environments? Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 7:105-118, 1997Google Scholar

18. Pickett SA, Lyons JS, Polonus T, et al: Factors predicting patients' satisfaction with managed mental health care. Psychiatric Services 46:722-723, 1995Link, Google Scholar

19. Tehrani E, Krussel J, Borg L, et al: Dropping out of psychiatric treatment: a prospective study of a first-admission cohort. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 94:266-271, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB: Outcomes of inpatients treated on a VA psychiatric unit and a substance abuse treatment unit. Psychiatric Services 48:699-704, 1997Link, Google Scholar

21. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB: Customer satisfaction and self-reported treatment outcomes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatric Services 49:929-934, 1998Link, Google Scholar

22. Lehman AF: The effects of psychiatric symptoms on quality of life assessments among the chronic mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 6:143-151, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Skantze K, Malm U, Dencker SJ: Comparison of quality of life with standard of living in schizophrenic outpatients. British Journal of Psychiatry 161:797-801, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Corrigan PW, Buican B: The construct validity of subjective quality of life in the severely mentally ill. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:281-285, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Collins JF, Casey NA, Hickey RH, et al: Treatment characteristics of psychiatric programs that correlate with patient community adjustment. Journal of Clinical Psychology 41:299-308, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Corrigan PW, Jakus MR: The Patient Satisfaction Interview for partial hospitalization programs. Psychological Reports 72:387-390, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Pascoe GC, Attkisson CC, Roberts RE: Comparison of indirect and direct approaches to measuring patient satisfaction. Evaluation and Program Planning 6:359-371, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Corrigan PW, Jakus MR: The reliability of severely mentally ill patients' reports of treatment satisfaction. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 3:215-219, 1993Google Scholar

29. Lehman AF: The well-being of chronic mental patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:369-373, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Lehman AF: A Quality of Life Interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

31. Bass BM, Avolio BJ: Transformational leadership and organizational culture. Public Administration Quarterly 17:112-121, 1993Google Scholar

32. Yammarino FJ, Bass BM: Person and situation views of leadership: a multiple levels of analysis approach. Leadership Quarterly 2:121-139, 1991Crossref, Google Scholar

33. Bass BM, Avolio BJ: Transformational Leadership Development: Manual for the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Palo Alto, Calif, Consulting Psychologists Press, 1993Google Scholar

34. Corrigan PW, Garman AN: Leadership skills for mental health and psychiatric rehabilitation teams. Community Mental Health Journal 35:301-312, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar