Social Functioning of Patients With Schizophrenia in High-Income Welfare Societies

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study assessed the level of reintegration into the community of patients with schizophrenia in Oslo, Norway, a country with a well-developed social welfare system and low unemployment rates. METHODS: Eighty-one patients with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia treated in 1980 and in 1983 in a short-term ward of a psychiatric hospital were followed up after seven years. Seventy-four of 76 patients alive at follow-up agreed to participate. Social functioning was measured by the Strauss-Carpenter Level of Functioning Scale and the Social Adjustment Scale. RESULTS: At follow-up 78 percent of patients lived independently, 47 percent were socially isolated, and 94 percent were unemployed. Thirty-four percent had lost employment in the follow-up period. A poor outcome in terms of social functioning and community reintegration was associated with loss of employment. A good outcome was predicted by short periods of inpatient hospitalization, high levels of education, being married, male gender, and not having a late onset of psychosis. CONCLUSIONS: The level of homelessness among these patients with schizophrenia was encouragingly low, which may have been expected in a high-income welfare society. However, insufficient efforts were aimed at social and instrumental rehabilitation, and the level of unemployment was alarmingly high.

Community reintegration has been one of the explicit goals of deinstitutionalization. Studies of patients' residential status show that a large percentage of patients manage to live independently, either alone or with family or friends (1), but their social support systems tend to be more poorly developed (2), and their occupational functioning tends to decline (3). The reduction of psychiatric beds has probably increased the number of homeless mentally ill persons, especially in the United States, but this increase has been questioned in European countries (4). Studies have shown better quality of life (5) and better clinical improvement among employed patients (6), which underscores the influence of social functioning on outcomes of psychosocial treatments (7).

Successful community integration depends on treatment resources, individual and family resources, and general community resources. The availability of housing and employment and the level of development of the social welfare system are important factors. One would expect that living in a well-developed social welfare system with low unemployment rates would be a good basis for community reintegration, but is this always the case?

The study reported here was done in Norway, a country with a well-developed social welfare system and low unemployment rates. Norwegian national health insurance ensures all inhabitants free inpatient medical care. The insurance also covers expenses in excess of an annually regulated patient's share for outpatient treatment, as well as medication for patients with long-term disorders including major depression and psychosis.

The national health insurance also finances sickness benefits, as well as rehabilitation, disability, and old-age benefits. The extent of the benefits is based on the person's income and number of working years. Persons without any previous income, such as students and homemakers, have a right to a low minimum benefit after one year of medical disability. Persons without income or with very low incomes are entitled to social security benefits that cover the basic necessities of food, clothing, and housing.

The study focused on patients with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia who were hospitalized at the short-term psychiatric ward of a general hospital and followed up after seven years. The ward was responsible for all emergency admissions from a suburban catchment area of approximately 60,000 inhabitants, which was developed by the city's housing cooperative in the 1960s and 1970s. The ward also had responsibility for a portion of the city's homeless population based on a person's date of birth. Two psychiatric outpatient clinics in the catchment area were responsible for outpatient treatment. Patients in need of long-term treatment were transferred to the local psychiatric hospital.

The study's follow-up period during the middle and late 1980s was characterized by low to moderate unemployment in the Oslo area, from .5 percent to 4.3 percent (8) and a 34 percent reduction in the number of beds in the city's psychiatric hospitals (9).

The study addressed several questions: What factors characterized patients' course over the follow-up period, and what factors were associated with patients' functioning at follow-up in the areas of housing, employment, income, and social contacts? What was the relationship between the different areas of social functioning? Which factors increased the probability of a good social outcome?

Methods

Subjects

Included in the study were all 81 patients with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder admitted in 1980 and 1983 to the acute ward at psychiatric department B of Ullevål Hospital in Oslo, Norway. The patients were followed up after a mean±SD of 84.4±8 months.

It was possible to trace all 81 patients. Five persons were dead, including three by suicide and two natural deaths. Sixteen patients did not want to participate in a personal interview but agreed to supply basic information in other ways—by telephone interviews, questionnaires, or interviews with their therapists. Only two patients were opposed to any kind of participation.

The follow-up sample consisted of 74 patients, 91 percent of the total and 97 percent of patients who were alive at follow-up. The sample consisted of 20 men (27 percent) and 54 women (73 percent). Throughout the study period, a large proportion of women with a diagnosis of schizophrenia were admitted from the catchment area to the study ward (9). No significant differences were found between the 74 patients included in the follow-up sample and the seven patients not included.

The catchment area consisted of new suburbs with mainly apartment blocks intermingled with detached housing and high-rise buildings. The inhabitants were mostly families with children who because of their younger age were at a low risk for schizophrenia. Twelve patients (16 percent) had only a primary education; in Norway, children are required to attend nine years of compulsory education, which comprises six years of primary school and three years of secondary school.

The mean±SD age of the sample at the index admission was 41±13.1 years, and the mean±SD age at the first episode of psychosis was 30.2± 10.7 years. At the index admission the mean±SD duration of illness was 10.8±9.9 years. Fourteen patients (19 percent) were at least 40 years old at the first episode of psychosis. The patients' treatment during their index admission has been previously described (10).

The median number of admissions prior to the index admission was four, with a range from none to 31. Thirteen patients (18 percent) had no previous admissions. The median number of admissions in the follow-up period was four, with a range from none to 17. The median duration of admissions during the follow-up period was 33 weeks, with a range from zero to 335 weeks. The majority of patients were in outpatient treatment throughout the follow-up period, with a mean±SD duration of antipsychotic treatment of 72.5±23.6 months.

Instruments

Two instruments were used to measure social functioning. The Strauss-Carpenter Level of Functioning Scale (SCLFS) (11) was used at the index admission and at follow-up. The SCLFS measures functioning in four areas: symptoms in the previous month and hospitalizations, work, and social contacts in the previous year. Functioning in each area is rated on a scale from 0, worst functioning, to 4, best functioning.

The Social Adjustment Scale (SAS) (12) measured social functioning cross-sectionally at the index admission; at one, two, three, four, and five years after the index admission; and at the study follow-up. The SAS score is a sum score of items in five areas of functioning. Independent housing is scored as one point if the patient lives in his or her own apartment or house and as no points if the patient is homeless, living in an institution, or being cared for by others. Contact with friends is scored as one point if the patient has friends outside the family and as no points if he or she is isolated. Work is scored as one point for paid employment and no points for being unemployed. Independent income is scored as one point if the patient receives wages or sickness or rehabilitation benefits and no points if the patient receives disability benefits, old-age benefits, or social or unemployment benefits. Treatment is scored as one point if the patient manages without treatment and as no points if he or she is receiving or in need of treatment. This scoring method gives a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 5.

The SAS scores and the SCLFS scores were calculated at follow-up based on information from the follow-up interviews, treatment charts, and national health insurance. To test the reliability of ratings, other psychiatrists blind to previous ratings reevaluated charts and interview audiotapes. Intraclass correlations (ICC 1.1) (13) for interval data ranged from .71 to .83. Kappa for the diagnostic categories (14) ranged from .70 at study entry to .73 at follow-up.

Statistical procedures

Analyses were carried out with SPSS version 7.5. For all group comparisons, the applied methods are indicated. All tests were two tailed. Nonparametric tests were used for data without normal distribution. Bivariate correlations are nonparametric (Kendall's tau b). Only variables with a significant bivariate relationship to the dependent variable in this study or variables identified as significant predictors in previous studies were entered in the multiple linear regression analysis. The variables were entered stepwise with one variable in each block. No interaction effects were noted.

The model was examined for nonlinear relationships between the dependent and independent variables by examining the beta coefficient for each of the independent variables' quartiles when that was appropriate. In the case of a nonlinear relationship, the independent variable was dichotomized at the threshold level indicated by the analysis. The final model was then examined for the effects of outliers and influential observations.

Results

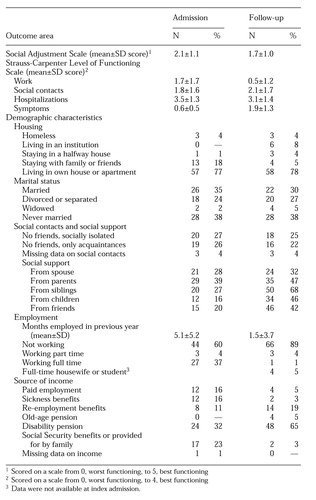

As Table 1 shows, global social functioning as measured by the SAS showed a steady decline from a mean±SD score of 2.1 at the index admission to 1.7 at follow-up (paired t test=2.63, df=73, p=.01).

Good global social functioning was defined as an SAS score of 3 or higher. At the index admission 27 patients (37 percent) had good global functioning; this number declined to 12 (16 percent) at follow-up (p=.02, Fischer's exact test). At follow-up only one patient (1 percent) received an SAS score of 5; three (4 percent) had a score of 4 because they did not manage without treatment. Eight (11 percent) had a score of 3, 25 (34 percent) a score of 2, 32 (43 percent) a score of 1, and five (7 percent) a score of 0.

Table 1 shows data on social functioning at admission and follow-up. The data indicated stable functioning across all areas except for a significant decrease in scores on the SCLFS work subscale (paired-samples t test=−6.2, df=71, p<.001,) and a nonsignificant trend (p=.08) for improvement in scores on the SCLFS social contacts subscale. Significant correlations were found (p<.01, Kendall's tau b) between patients' status at index admission and follow-up on three variables—marital status (correlation coefficient=.70), the SAS independent housing subscale (correlation coefficient=.40), and the SAS social contacts subscale (correlation coefficient=.52). No significant correlations were found between the two time points in scores on the SAS employment subscale and the SAS independent income subscale.

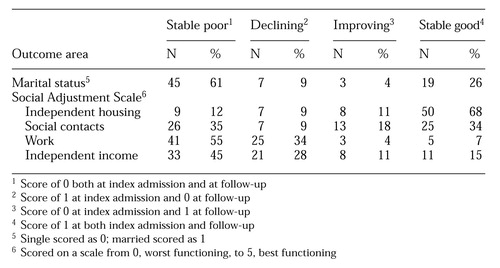

Data in Table 2 on individual patients illustrate the stable functioning in independent housing and marital status and the trend toward a slight improvement in social contacts. At follow-up the number of institutionalized patients had increased slightly, while the number of patients living in others' homes had decreased (Table 1). Only three patients (4 percent) were homeless at the index admission, and another three (4 percent) were homeless at follow-up. No patient was homeless at both time points.

Levels of support from spouses and parents were stable across the follow-up period, but a nonsignificant trend toward an increase in support from siblings, children, and friends was noted (Table 1).

At follow-up single patients were as likely as married patients to have contact with friends outside the family; 64 percent of the patients in both the married and the single groups had such contacts. However, married patients were in touch with a greater number of persons than single patients (a mean of four persons versus a mean of three; Z=−4.4, p<.001, Mann-Whitney U test).

The downward trend in social functioning as measured by work and independent income was conspicuous (Table 2). The number of months employed during the preceding year (Table 1) decreased significantly (paired-sample t test=−5.5, df=68, p<.001). However, the number of patients who were living on social security benefits or who were provided for by their family decreased significantly (z=−3.6, p<.001, Wilcoxon signed rank test). The main source of income at both time points was disability benefits.

The correlations between patients' courses in the different outcome areas shown in Table 2 were low. A significant association was found between developments in marital status and housing (correlation coefficient=.32, p<.001, Kendall's tau b), indicating that patients who were divorced or widowed were the most likely to become institutionalized or homeless. Development in independent income was strongly associated with development in employment (correlation coefficient=.54, p<.001, Kendall's tau b).

Female patients appeared to have significantly lower mean SAS scores at follow-up than male patients (2.2±1.2 versus 1.5±.8; independent-samples t test=2.7, df=72, p=.01). Single patients had lower mean SAS scores than married patients (1.5±.9 versus 2.1±1.1; independent-samples t test=−2.2, df=72, p=.03). Patients with nine years or less of education also had lower mean SAS scores than patients with a higher level of education (1.5±.8 versus 2.7±1.3; independent-samples t test =−4.2, df=72, p<.001).

The SAS total score at follow-up correlated significantly with the SAS total score at index admission (correlation coeffient=.29, p<.01, Kendall's tau b) and with all SAS subscale scores at the same time point. The highest correlation was with the work subscale (correlation coefficient=.57, p<.001, Kendall's tau b). SAS scores at follow-up did not correlate significantly with age at index admission, age at onset of psychosis, or the duration of patients' hospitalizations in the follow-up period.

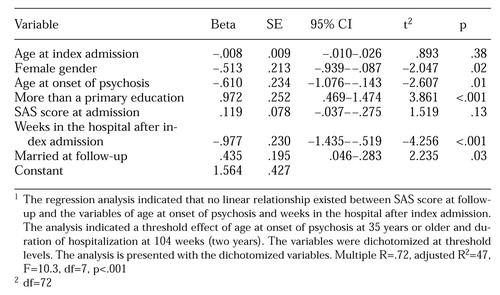

Because several of the variables were interdependent, their relationship with the SAS scores at follow-up was explored through a multivariate analysis. As shown in Table 3, gender, onset of illness before age 35, being hospitalized for less than two years in the follow-up period, being married, and having more than nine years of education were significantly associated with higher SAS scores.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicated good outcomes in the area of independent living. Most of the 74 patients in the sample managed to live in noninstitutional settings throughout the follow-up period. The study confirms that the safety net of the Norwegian welfare system that ensures all inhabitants a place to live and a minimum income was working satisfactorily. Few patients were homeless, and few were living mainly from social security benefits.

Nevertheless, average income was low. Our visits to patients' homes often showed us sparsely furnished flats and signs of deficient domestic skills. In some cases, it was obvious that the patient could manage outside the hospital only because of major efforts from his or her family.

The outcome data are more questionable in the area of social contacts. The SCLFS social contacts score at follow-up (mean=2.1) is in the same range as scores in several recent medium-length follow-up studies, which found mean scores of 2 to 3 over periods of five to ten years (15,16,17,18), higher than scores in recent long-term studies in which the mean scores ranged from .7 to 1.4 over periods of 15 to 39 years (19,20). Indications were noted in our study of improvements in social contacts and social support over the follow-up period. However, social isolation for half of the patients is not a good outcome. Additional indications were found that that patients' social networks were passive. The main support network was patients' families, and married patients had more members of their networks than single patients.

The course of patients' employment status over the follow-up period is a cause of concern. Most patients with severe mental illnesses identify paid employment as one of their goals (21). Employment has several positive consequences: an increase in social networks, higher incomes, and improvements in self-esteem, in addition to possible effects on clinical outcome (5,6). The follow-up SCLFS work subscale score in our study (mean=.5) is clearly lower than in other studies, which have found mean scores ranging from 1.0 to 1.9 (15,16,17,18,19,20). Meta-analyses from the United States have found pooled rates for paid employment of 29 percent among psychiatric patients with schizophrenia and those with other diagnoses who had not received vocational rehabilitation (21). European studies of patients with schizophrenia indicate employment rates in the 15 to 38 percent range (22,23,24), and Nordic studies indicate employment rates in the range of 12 to 21 percent (18,20,25,26,27).

An extensive Finnish study of patients with schizophrenia or a major affective disorder found employment rates from 3 percent among men who were unemployed 18 years before the study to 27 percent among women who had been engaged in upper-white-collar work 18 years earlier (3). The same study also demonstrated a constant downward drift in employment status, but to a smaller extent and over longer intervals than in our study.

Even though the follow-up intervals in these studies as well as patients' demographic characteristics and the diagnostic composition of the samples were different from those in our study, the level of employment found in our study is clearly lower than expected. The unemployment rate in the follow-up period was moderate to low, and the patient's massive loss of work over the period cannot be explained by general unemployment forcing patients with marginal functioning out of the workforce (8).

The demographic characteristics of the patients probably influenced the study's findings to some extent. The large proportion of female patients may have decreased the risk of homelessness and increased the probability of high levels of social contacts. However, the multiple linear regression analysis indicated that female gender, together with older age at the onset of psychosis, surprisingly increased the risk of poor social functioning at follow-up.

The explanation lies most probably in the significant association between poor social functioning and loss of employment in the follow-up period, which may also explain the impact of education level. The high mean age of onset of psychosis for the sample—30.2 years—suggests that the association between length of education and outcome was not mediated by the interruption of education due to onset of psychosis as suggested in other studies (28). In our study education seemed to entail expectations of further employment by both patients and the treatment system. Broader ranges of working skills facilitate adaptation to a broader range of working situations. The Norwegian wage level is high, and few jobs for unskilled workers are available. Level of education has previously been shown as a predictor of employment for refugees, another group with employment difficulties in Norway (29).

National disability pension policies may serve as disincentives for employment (5), especially the availability of disability benefits for patients with a marginal working capacity. In the follow-up period there was a strong political belief in integrating psychiatric patients into general reemployment services, which contradicts evidence that patients with schizophrenia need tailored rehabilitation interventions (30,31). In addition to the general downsizing of inpatient services, several vocational rehabilitation centers were closed down. The idea that schizophrenia is a disorder that mainly affects young males may have blocked access to the remaining rehabilitation services for the large proportion of women in our study, many of whom had a later onset of illness.

The expectation that these patients should adapt to general reemployment services not modified to their needs would make retirement with disability benefits the easiest way out for patients with low employment capability. A parallel situation is evident in the early 1990s when changes in Norway's national health insurance facilitated the changeover to disability benefits for patients with chronic disorders; these changes appear to have worsened conditions for psychosocial rehabilitation, especially for persons with mental disorders (32).

Conclusions

Like other studies, this study demonstrates that outcome for patients with schizophrenia comprises "loosely linked domains of human functioning" (11). The study confirms the existence of the safety net of the welfare society. Very few patients were homeless or without economic means at follow-up. However, the level of community integration was low. Half of the patients were socially isolated, and a third had lost their employment, even though many patients had characteristics most often associated with a good outcome in schizophrenia.

The study demonstrates that patients with schizophrenia, given the necessary practical and economical means, can live in the community and avoid homelessness. However, the results suggest that active rehabilitation is needed to achieve community reintegration, even for patients with developed social skills. It appeared as if the group of older female patients stood on the wrong side of the door when it came to accessing limited rehabilitation services, and their access to disability benefits made retirement the easiest way out for the treatment system.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Thor Kristian Island, M.D., and Steinar Lorentzen, M.D., for their contributions in planning and carrying out the first part of the study. The study was supported by grants from the Norwegian Council for Mental Health (RÅdet for Psykisk Helse), the Jonn-Nilsen Family Bequest (Jonn-Nilsens Legat), Sommer's Charitable Institution (Sommers Stiftelse), and the Anders Jahre's Foundation (Anders Jahres Fond).

Dr. Melle is clinical director, Dr. Friis is research director, and Dr. Hauff is director of education in the department of research and education of the division of psychiatry at UllevÅl University Hospital, N-0407 Oslo, Norway (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Friis is also professor of psychiatry and Dr. Vaglum is professor of behavioral sciences at the University of Oslo.

|

Table 1. Social functioning of 74 patients with schizophrenia at index admission and seven-year follow-up

|

Table 2. Development of social functioning in the different outcome areas for 74 patients with schizophrenia during a seven-year follow-up period

|

Table 3. Multiple linear regression of relationship between patients' score on the Social Adjustment Sales (SAS) at follow-up and patients variables1

1. Harrison G, Mason P, Glazebrook C, et al: Residence of incident cohort of psychotic patients after 13 years of follow-up. British Medical Journal 308:813-816, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Haberfellner EM, Rittmannsberger H: Social relations and social support of psychiatric patients: a network study [in German]. Psychiatrische Praxis 22:145-149, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

3. Aro S, Aro H, Keskimaki I: Socio-economic mobility among patients with schizophrenia or major affective disorder: a 17-year retrospective follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 166:759-767, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Geddes J, Newton R, Young G, et al: Comparison of prevalence of schizophrenia among residents of hostels for homeless people in 1966 and 1992. British Medical Journal 308:816-819, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Priebe S, Warner R, Hubschmid T, et al: Employment, attitudes toward work and quality of life among people with schizophrenia in three countries. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:469-477, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Bell MD, Lysaker PH: Clinical benefits of paid work activity in schizophrenia:1-year follow-up. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:317-328, 1997Google Scholar

7. Hogarty GE, Kornblith SJ, Greenwald D, et al: Three-year trials of personal therapy among schizophrenic patients living with or independent of family: I. description of study and effects on relapse rates. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1504-1513, 1997Link, Google Scholar

8. Historical statistics of the employment market [in Norwegian]. Oslo, Norwegian Directorate of Employment, 1997Google Scholar

9. Oslo City Psychiatric Information System. Oslo, Oslo City Council, 1991Google Scholar

10. Melle I, Friis S, Hauff E, et al: The importance of ward atmosphere in inpatient treatment of schizophrenia on short-term units. Psychiatric Services 47:721-726, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Strauss J, Carpenter WT Jr: The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia: I. the characteristics of outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 27:739-746, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Petersen E: Stofmisbrugere: Drug Abusers: Voluntary Treatment [in Danish]. Copenhagen, Mental Hygiene Publishing House, 1974Google Scholar

13. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin 86:420-428, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Spitzer RL, Cohen J, Fleiss JL: Quantification of agreement in psychiatric diagnosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 17:83-87, 1967Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Harrow M, Sands J, Silverstein ML, et al: Course and outcome for schizophrenia versus other psychotic patients: a longitudinal study. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:287-303, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, et al: Course of illness and predictors of outcome in chronic schizophrenia: implications for psychopathology. British Journal of Psychiatry 161(suppl 18):38-43, 1992Google Scholar

17. Tsuang D, Coryell W: An 8-year follow-up of patients with DSM-III-R psychotic depression, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1182-1188, 1993Link, Google Scholar

18. Wieselgren IM, Lindstrom LH: A prospective 1-5 year outcome study in first-admitted and readmitted schizophrenic patients: relationship to heredity, premorbid adjustment, duration of disease, and education level at index admission and neuroleptic treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 93:9-19, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. McGlashan TH: The Chestnut Lodge follow-up study: II. long-term outcome of schizophrenia and the affective disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:586-601, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Opjordsmoen S: Delusional disorders: I. comparative long-term outcome. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 80:603-612, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Lehman AF: Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:645-656, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Schmid GB, Stassen HH, Gross G, et al: Long-term prognosis of schizophrenia. Psychopathology 24:130-140, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Häfner H, an der Heiden W: Effectiveness and cost of community care for schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:59-64, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

24. Shepherd M, Watt D, Falloon I, et al: The Natural History of Schizophrenia: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study of Outcome and Prediction in a Representative Sample of Schizophrenics. Psychological Medicine Monograph (suppl 15), 1989Google Scholar

25. Munk-Jorgensen P, Mortensen PB: Social outcome in schizophrenia: a 13-year follow-up. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 27:129-134, 1992Medline, Google Scholar

26. Helgason L: Twenty-year follow-up of first psychiatric presentation of schizophrenia: what could have been prevented? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 81:231-235, 1990Google Scholar

27. Palmquist J, Wang AG: Schizophrenia in the Faroe Islands. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 51:351-357, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Daradkeh TK, Karim L: Predictors of employment status of treated patients with DSM-III-R diagnosis: can a logistic regression model find a solution? International Journal of Social Psychiatry 40:141-149, 1994Google Scholar

29. Hauff E, Vaglum P: Integration of Vietnamese refugees into the Norwegian labour market: the impact of war trauma. International Migration Review 27:388-405, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

30. Lysaker P, Bell M, Beam-Goulet J: Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and work performance in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research 56:45-50, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry 153:321-330, 1996Google Scholar

32. Bjerkedal T: Disability pensions in young age in Norway during 1976-1996 [in Norwegian]. Tidsskrift for Den Norske Laegeforening 118:2305-2307, 1998Medline, Google Scholar