Intramuscular Flunitrazepam Versus Intramuscular Haloperidol in the Emergency Treatment of Aggressive Psychotic Behavior

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors examined the efficacy of intramuscular flunitrazepam compared with intramuscular haloperidol for the immediate control of agitated or aggressive behavior in acutely psychotic patients. METHOD: Twenty-eight actively psychotic inpatients, aged 20–60 years, who were under treatment with neuroleptic agents were selected for the study. Each was randomly assigned on a double-blind basis to receive either 5 mg i.m. of haloperidol (N=13) or 1 mg i.m. of flunitrazepam (N=15) during an aggressive event. Verbal and physical aggression was measured over time with the Overt Aggression Scale. Patients were also rated with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and the Clinical Global Impression scale. RESULTS: Both flunitrazepam and haloperidol exhibited acute antiaggressive activity. This beneficial effect, as assessed by the Overt Aggression Scale, was obtained within 30 minutes. CONCLUSIONS: Intramuscular flunitrazepam may serve as a convenient, rapid, safe, and effective adjunct to neuroleptics in reducing aggressive behavior in emergency psychiatric settings.

Benzodiazepines have recently gained interest as a class of drugs for use as alternatives or adjuncts to ongoing antipsychotic agents in emergency settings (1). Lorazepam and diazepam, administered parenterally, have been shown to be a good alternative to parenteral haloperidol for the immediate control of psychotic aggressive or disruptive behavior (2, 3) and as an adjunct to lithium in the clinical management of early manic agitation in bipolar patients (4). Intramuscular lorazepam has emerged as the benzodiazepine of choice for immediate control of psychotic disruptive behavior (5). Alprazolam, when combined with haloperidol, is also particularly effective in the initial hours of treatment of acutely psychotic schizophrenic patients (6). Intramuscular clonazepam, however, acts more slowly than intramuscular haloperidol (7). Chlordiazepoxide and diazepam are rarely used because their intramuscular administration is associated with prolonged sedation and erratic absorption and is therefore not superior to oral administration (8). This is not true for flunitrazepam, whose intramuscular absorption corresponds to its absorption through the oral route (9). To date, flunitrazepam has been investigated primarily as a hypnotic agent in patients with insomnia and in anesthesiology (10). The purpose of the present study was to prospectively investigate the efficacy of intramuscular flunitrazepam versus intramuscular haloperidol in the acute treatment of aggressive psychotic inpatients.

METHOD

The study group included 28 patients (13 men and 15 women), of whom 19 had schizophrenia, seven had schizoaffective disorder, and two had bipolar disorder. All diagnoses were established according to DSM-IV criteria after a clinical interview in which the guidelines of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (11) were used. Inclusion criteria for the study were the presence of active psychosis; disruptive or aggressive behavior, pronounced psychomotor agitation, or violent outbursts; and hospitalization in an acute ward.

Patients were assigned by a table of random numbers, on a double-blind basis, to receive either 5 mg i.m. of haloperidol (N=13, five men and eight women; mean age=36.8 years, SD=15.1) or 1 mg i.m. of flunitrazepam (N=15, eight men and seven women; mean age=34.9 years, SD=8.1) during an acute aggressive outburst. Follow-up evaluation was performed with the Overt Aggression Scale (12), a 16-item index specifically designed to assess verbal and physical aggression toward objects, the self, or others. Measurements were made at baseline and at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes. All ratings were completed by the same rater (N.K.), who was blind to the study medications. Overall response to treatment was defined as a reduction of at least 50% in Overt Aggression Scale score at 90 minutes. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale were also administered at baseline to assess the severity of psychotic symptoms.

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Geha Psychiatric Hospital, Tel Aviv. The need for informed consent was waived by the board, since both study medications are considered acceptable and consistent in clinical settings where rapid control of aggressive, disruptive behavior is needed.

Repeated measures analysis of variance and Fisher’s exact test were used as appropriate in the statistical analyses.

RESULTS

There were no significant differences between the haloperidol and flunitrazepam groups in diagnostic entities (12 schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders and one bipolar I disorder versus 14 schizophrenic and schizoaffective disorders and one bipolar I disorder), in BPRS variables (mean score=49.0, SD=6.6, versus mean=45.4, SD=6.7), and in CGI scores (mean=4.5, SD=0.5, versus mean=4.5, SD=0.7). The antipsychotic drug treatment was similar in both groups; in the haloperidol group: perphenazine, 5–20 mg/day (N=5); haloperidol, 5–10 mg/day (N=4); levomepromazine, 50 and 200 mg/day (N=2); and zuclopenthixol, 25 mg/day (N=2); in the flunitrazepam group: perphenazine, 5–20 mg/day (N=4); haloperidol, 5–15 mg/day (N=6); levomepromazine, 75 mg/day (N=1); and zuclopenthixol, 25–50 mg/day (N=4). Four patients (two in each group) were taking additional medications including mood stabilizers (carbamazepine and valproic acid) and lorazepam.

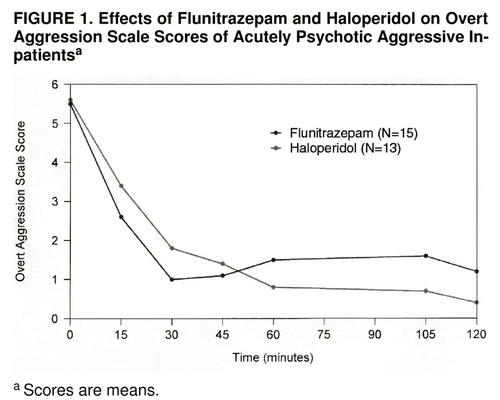

As shown in figure 1, the acute administration of either flunitrazepam, 1 mg i.m., or haloperidol, 5 mg i.m., resulted in a significant reduction in Overt Aggression Scale score (F=72.42, df=6, 156, p<0.001, time effect). However, the maximal antiaggressive effect of flunitrazepam was already achieved 30 minutes after administration, whereas the activity of haloperidol increased gradually. This difference in antiaggressive effect was significant (F=3.10, df=6, 156, p<0.01, time-by-group interaction). In both groups the reduced aggression level lasted for at least 120 minutes following drug administration. No restraint or seclusion was used in either group.

The rate of response reduction in total Overt Aggression Scale score at 90 minutes was 80% (N=12) of the 15 patients in the flunitrazepam group and 92% (N=12) of the 13 in the haloperidol group (p=0.34, Fisher’s exact test). Flunitrazepam and haloperidol each induced marked sedation in three patients.

DISCUSSION

The use of benzodiazepines in schizophrenia, either alone or in addition to antipsychotics, has been widely studied, but their efficacy remains unclear. Cohen and Khan (13) emphasized that when benzodiazepines are used as adjuncts to neuroleptics in the acute treatment of psychotic patients, the major effect is an overall decrease in total neuroleptic dosage. However, most studies of benzodiazepines as neuroleptic adjuncts in schizophrenia have been based on weekly ratings and are not relevant for acute or emergency treatment (6). To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to investigate the beneficial effect of intramuscular flunitrazepam as an adjunct to neuroleptics in the short-term treatment of acute psychotic aggressive behavior.

We found that flunitrazepam and haloperidol administered intramuscularly were similarly effective in controlling agitated or aggressive behavior in acute psychotic inpatients. The antiaggressive effect of both was reached within 30 minutes. These results confirm earlier studies showing that an intramuscular benzodiazepine, used as an adjunct to ongoing antipsychotic treatment, is equally efficacious as, or superior to, haloperidol added to ongoing neuroleptic treatment (1, 2). It should be noted that the antiaggressive effect of flunitrazepam had worn off at 60 minutes, whereas the effect of haloperidol persisted over 120 minutes (figure 1); however, this difference was not clinically relevant.

No acute extrapyramidal events were observed in either group. Although the use of benzodiazepines has been associated with assaultive behavior (14), the incidence of clinically adverse sequelae is thought to be less than 1%. We did not observe any excitation or disinhibition in the patients receiving flunitrazepam. Because sedation and reduced anxiety and agitation are probably the most prominent effects of benzodiazepines, the acute management of aggression in disruptive psychotic patients is the most well-founded indication for their adjunctive use in schizophrenic patients. This is particularly true for flunitrazepam, whose hypnotic action predominates over its sedative, anxiolytic, muscle-relaxing, and anticonvulsant effects. A potential advantage of flunitrazepam over lorazepam is its slightly longer half-life (19–22 hours versus 10–20 hours), allowing for prolonged antiaggressive action (15, 16). It is the unaltered drug, not its metabolites, that is primarily responsible for the clinical effects (10). Although it is not currently marketed in the United States, flunitrazepam is available in Europe and Latin America. Head-to-head comparison of flunitrazepam with lorazepam is warranted.

Our study was limited by the relatively small number of participants, the diagnostic complexity of the group studied, the variability in the antipsychotic pharmacotherapy, and the lack of a placebo control group. Blood levels of haloperidol and flunitrazepam were not measured. Although further large-scale placebo-controlled studies are needed, it appears that flunitrazepam, administered intramuscularly, may be a safe, rapid, and effective adjunct to neuroleptics in emergency psychiatric settings.

Received Feb. 13, 1998; revision received June 24, 1998; accepted July 6, 1998. From the Talbieh Mental Health Center, Hebrew University Faculty of Medicine; and Geha Psychiatric Hospital, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. Address reprint requests to Dr. Dorevitch, Talbieh Mental Health Center, 18 Disraeli St., P.O. Box 4487, Jerusalem 91000, Israel.

FIGURE 1. Effects of Flunitrazepam and Haloperidol on Overt Aggression Scale Scores of Acutely Psychotic Aggressive Inpatientsa

aScores are means.

1. Foster S, Kessel J, Berman ME, Simpson GM: Efficacy of lorazepam and haloperidol for rapid tranquilization in a psychiatric emergency room setting. Int Clin Pyschopharmacol 1997; 12:175–179Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Salzman C, Solomon D, Miyawaki E, Glassman R, Rood L, Flowers C, Thayer S: Parenteral lorazepam versus parenteral haloperidol for the control of psychotic disruptive behavior. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52:177–180Medline, Google Scholar

3. Lerner Y, Lwow E, Levitan A, Belmaker RH: Acute high-dose parenteral haloperidol treatment of psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 1979; 136:1061–1064Link, Google Scholar

4. Lenox RH, Newhouse PA, Creelman WL, Whitaker TM: Adjunctive treatment of manic agitation with lorazepam versus haloperidol: a double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53:47–52Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bodkin JA: Emerging uses for high-potency benzodiazepines in psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1990; 51(suppl 5):41–46Google Scholar

6. Barbee JG, Mancuso DM, Freed CR, Todorov AA: Alprazolam as a neuroleptic adjunct in the emergency treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1992; 149:506–510; correction, 149:1129Link, Google Scholar

7. Chouinard G, Annable L, Turnier L, Holobow N, Szkrumelak N: A double-blind randomized trial of rapid tranquilization with IM clonazepam and IM haloperidol in agitated psychotic patients with manic symptoms. Can J Psychiatry 1993; 38(suppl 4):S114–S121Google Scholar

8. Salzman C: Use of benzodiazepines to control disruptive behavior in inpatients. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49(suppl 12):13–15Google Scholar

9. Mattila MAK, Larni HM: Flunitrazepam: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use. Drugs 1980; 20:353–374Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Wickstrom E, Amrein R, Haefefinger P, Hartman D: Pharmacokinetic and clinical observations on prolonged administration of flunitrazepam. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1980; 17:189–196Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-P), version 2. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1995Google Scholar

12. Yudofsky SC, Silver JM, Jackson W, Endicott J, Williams D: The Overt Aggression Scale for the objective rating of verbal and physical aggression. Am J Psychiatry 1986; 143:35–39Link, Google Scholar

13. Cohen S, Khan A: Adjunctive benzodiazepines in acute schizophrenia. Neuropsychobiology 1987; 18:9–12Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Dietch JT, Jennings JT: Aggressive dyscontrol in patients treated with benzodiazepines. J Clin Psychiatry 1988; 49:184–188Medline, Google Scholar

15. Davis PJ, Cook DR: Clinical pharmacokinetics of the new intravenous anesthetic agents. Clin Pharmacokinet 1986; 11:18–35Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Hoey LL, Nahum A, Vance-Bryan K: A retrospective review and assessment of benzodiazepines in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal in hospitalized patients. Pharmacotherapy 1994; 14:572–578Medline, Google Scholar