Olanzapine Compared With Chlorpromazine in Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy of olanzapine with that of chlorpromazine plus benztropine in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. METHOD: One hundred three previously treatment-resistant patients with schizophrenia diagnosed according to the DSM-III-R criteria were given a prospective 6-week trial of 10–40 mg/day of haloperidol. Eighty-four of them failed to respond to that trial and agreed to be randomly assigned to an 8-week fixed-dose trial of either 25 mg/day of olanzapine alone or 1200 mg/day of chlorpromazine plus 4 mg/day of benztropine mesylate. RESULTS: Fifty-nine (70%) of the 84 subjects completed the trial. The primary outcome measures were Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale total score and positive symptom score, Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms global score, and Clinical Global Impression score. An analysis of variance for the subjects who completed the study showed no difference in efficacy between the two drugs. Seven percent of the olanzapine-treated patients responded according to a priori criteria; no chlorpromazine-treated patients responded. The olanzapine-treated patients had fewer motor and cardiovascular side effects than the chlorpromazine-treated patients. Extrapyramidal symptoms and akathisia were similar in the two groups, although no antiparkinsonian drugs were used in the olanzapine group. CONCLUSIONS: Olanzapine and chlorpromazine showed similar efficacy, and the total amount of improvement with either drug was modest. Olanzapine-treated patients had fewer side effects than chlorpromazine-treated patients. (Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:914–920)

Fifteen to twenty-five percent of all persons with schizophrenia experience little clinical improvement with antipsychotic drug treatment (1). This percentage is based on findings that have been consistently reported over many years (2–4). Not only is the recovery of these individuals compromised, but their treatment as a group is a persistent public health problem. Patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia remain highly symptomatic and require extensive periods of hospital care (5), which contributes disproportionately to the overall cost of treating schizophrenia (6).

Drug therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia formerly included either high doses of traditional antipsychotics or the use of adjunct agents such as lithium, antidepressants, β-blocking drugs, anticonvulsants, or benzodiazepines (7, 8). Clozapine was the first effective therapy for this condition (9). However, clozapine treatment entails substantial morbidity from serious side effects, a measurable mortality rate, and the need for blood monitoring. As new antipsychotics become available for clinical use, it is imperative for theoretical as well as therapeutic reasons to test these drugs for efficacy in neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia.

Resistance to treatment, to a partial degree, characterizes 70%–80% of persons with schizophrenia. A multicenter clozapine trial (9) operationally defined “treatment resistance” as a categorical diagnosis. In the clinic, however, response to treatment is a continuum from poor to full remission of symptoms. Clear and consistent nonresponse criteria are important in carrying out and comparing studies in this area.

The most widely accepted criteria for identifying treatment resistance in schizophrenia are those used by Kane et al. (9). The group defined by these criteria consists of persons persistently ill with schizophrenia who have undiminished positive symptoms despite adequate antipsychotic drug treatment. Using similar nonresponse criteria for defining patient populations, recent studies have replicated findings of clozapine's superior antipsychotic efficacy in treatment-resistant schizophrenia (10–12).

= The criteria for full nonresponse in schizophrenia have been modified only minimally since their initial application. Currently, two retrospective drug trial failures are commonly used instead of three (8). Kinon et al. (13) demonstrated that subjects whose illness is not responsive to two adequate antipsychotic trials (one retrospective and one prospective) have less than a 7% chance of responding to any future traditional antipsychotic drug. This criterion is consistent with the guidelines for clozapine use approved by the Food and Drug Administration that are included in its package insert.

Olanzapine is a structural congener of clozapine and has a similar pharmacologic profile. This includes a clinically relevant affinity for D1–D5 dopamine receptors, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT6 serotonin receptors, and M1 muscarinic, H1 histamine, and adrenergic receptors. Like clozapine, olanzapine retains most of the behavioral effects of traditional antipsychotics in models of antipsychotic action but produces no catalepsy (14). Other similarities to clozapine include olanzapine's apparent anatomic selectivity in the dopamine neuronal depolarization blockade model and in functional anatomy studies using Fos protein activation (15). A major difference between the two drugs is the high affinity of olanzapine for D2 dopamine receptors and its high-dose potency.

Olanzapine has been demonstrated to have antipsychotic efficacy in schizophrenia at doses of 5–20 mg/day in treatment-responsive patients (16). It is clinically equivalent to haloperidol in treating positive symptoms and shows superiority in reducing negative symptom ratings. It causes few extrapyramidal side effects and only transient prolactin elevations (16). These types of advantages are also seen with use of clozapine in treatment-responsive patients (17). Olanzapine has not yet been tested in a controlled fashion in patients with treatment-resistant illness to see whether it shares clozapine's critically important superior efficacy in this population.

Chlorpromazine is a low-potency traditional antipsychotic; it was the first drug demonstrated to have antipsychotic characteristics (3), and it was the control drug in the Kane et al. study (9). Olanzapine has anticholinergic properties, and chlorpromazine (with adjunct benztropine) has a low probability of producing motor side effects. Therefore, some overlap of side effects between these two drugs is likely, and chlorpromazine was chosen to enhance the blinding in this study.

METHOD

The 103 volunteers for this study were physically healthy inpatients. The subjects were recruited at three clinical sites in Maryland. Each subject, after a review of all medical records, a Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (18), and a direct clinical interview, met the DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia.

In addition, all subjects met criteria for treatment resistance. These criteria were as follows: 1) at least two periods of treatment in the preceding 5 years with an antipsychotic drug (from at least two different chemical classes, excluding haloperidol), at dosages ≥1000 mg/day of chlorpromazine equivalents, for 6 weeks without significant symptomatic relief; 2) no period of good functioning within the past 5 years; and 3) severity of psychopathology indicated by a total score of 45 or more on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (19) (items rated 1–7), a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (20) severity score of 4 or more, and a score of 4 or more on at least two of the BPRS psychosis items (conceptual disorganization, suspiciousness, hallucinatory behavior, and unusual thought content). These criteria differ from the criteria in the Kane et al. study (9) in that those investigators used three retrospective treatment failures, which could include haloperidol. Subjects in the present study could have had prior clozapine treatment but could not have demonstrated resistance to clozapine.

Subjects' physical health was confirmed by medical examination, standard laboratory tests, a chest X-ray, and a baseline ECG. Each subject also gave written informed consent after being evaluated as able to consent by the Ability to Sign Consent Interview (21). To make the consent process more thorough, each subject was included in a psychoeducational process to explain issues about the study in depth. The study was approved by each participating institution's review board.

Clinical Procedures

After the initial screening, subjects were given a prospective trial of haloperidol, 10–40 mg/day, and benztropine, 4 mg/day, for a period of 6 weeks. Haloperidol dosing was open and done by the treating psychiatrist. Failure to respond to the haloperidol trial was defined as less than a 20% decrease in total BPRS score, an endpoint BPRS score greater than 35, and a CGI severity score greater than 4 for patients completing at least 2 weeks of haloperidol therapy.

Of the 103 subjects, 84 qualified for the study by showing no response to haloperidol and agreed to continue participating. They were randomly assigned to an 8-week fixed-dose, double-blind trial with either olanzapine (25 mg/day) or chlorpromazine (1200 mg/day) plus benztropine mesylate (4 mg/day). Subjects remained hospitalized throughout the study.

The double-blind trial began after a 1- to 2-week washout period following the haloperidol qualifying trial. Subjects received olanzapine tablets or matching placebo tablets, chlorpromazine elixir or similar-tasting placebo elixir, and benztropine mesylate tablets, 2 mg b.i.d. (chlorpromazine group), or placebo tablets (olanzapine group). During the first week of this trial, the dosage of the study medications was either 12.5 mg/day of olanzapine or 600 mg/day of chlorpromazine plus 4 mg/day of benztropine mesylate. Starting at week 2, doses were increased to the full amount. If at any time in the trial patients were intolerant of the higher dose, they could receive the lower initial dose for up to 9 days, at which point they had to be returned to the higher-dose therapy or be dropped from the study. Patients were allowed no more than two such dose decreases during the double-blind period. During the washout period and the first 3 weeks of double-blind medication, patients were also allowed to receive lorazepam (up to 8 mg/day) for agitation or anxiety. No other centrally acting medications were administered during the study.

Sites

This study was performed at three Maryland hospitals: Spring Grove Hospital Center, Perry Point Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center, and Upper Shore Hospital Center. One central research team, composed of two psychiatrists (R.R.C. and C.R.), a psychologist, a nurse (S.Z.), a social worker, an activity therapist, and two study coordinators (C.G. and J.L.), made all research assessments. This team also conducted all recruitment, diagnostic, and response rating evaluations at all three sites. The research team was based at Spring Grove Hospital Center. Team members visited the other hospitals at least weekly throughout the study to perform the research ratings at those sites. Initial interviews for study entry and weekly clinical chart reviews during the study were done by a team member at all sites.

The local clinical team at each hospital ordered the study drugs, which were dispensed by the local pharmacies under a blind protocol maintained by a central research pharmacy. The local hospital sites provided routine daily care of the patients, performed phlebotomies, and monitored vital signs. The nonresearch clinicians involved with the patients could prescribe lorazepam as allowed by the study but could not prescribe any other psychoactive medication during the study. The research team monitored all participant activities and events weekly.

Efficacy and Safety Ratings

The BPRS was used as the primary efficacy measure; the CGI was used for determining general psychiatric status; the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (22) for evaluating negative symptoms; the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale (23) for assessing parkinsonian symptoms; and the Barnes Akathisia Scale (24) for assessing akathisia. Data on the frequency of nonmotor side effects were collected from patients' reports, chart review, and weekly examinations by physicians and research team members.

Before participating in research ratings, each rater on the research team was trained and demonstrated acceptable interrater agreement (intraclass correlation coefficient greater than 0.80) with standard videotaped BPRS ratings done by five senior raters at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. Raters were assessed at regular reliability sessions to ensure that interrater agreement remained above 0.80 throughout the study. Raters were also systematically trained on the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale, the Barnes Akathisia Scale, and the SANS.

Data Analysis

Differences between the two drug groups in categorized background variables were assessed by chi-square analysis. Differences in these same background variables among the three sites were compared by means of the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for categorical variables and two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (for continuous variables) with treatment as a factor.

Of the 103 patients who entered the study, 81 had baseline and time course data, although only 59 had complete data. Repeated measures ANOVA procedures were performed for both groups, but for the 81 patients the last-observation-carried-forward procedure was used. Repeated measures ANOVAs of baseline versus endpoint data were also performed for the completers and those with data from the last observation carried forward. Two-tailed tests were used throughout. The primary measures of efficacy, designated a priori, were the percentages of patients showing significant clinical improvement (defined as at least a 20% reduction in the total BPRS score compared to the baseline score and a posttreatment CGI score ≤3 or a posttreatment BPRS score ≤35), total BPRS score, score on the cluster of four key BPRS items, and SANS total global score. All other analyses were considered secondary. To account for multiple comparisons, the four main outcome variables were tested at the alpha level of 0.05; the remaining variables were grouped and corrected for post hoc effects, which resulted in their being tested at the 0.01 level for significance.

To test the appropriateness of presenting only completer and endpoint analyses of our data, we conducted more extensive analyses of BPRS total score, score on the cluster of four key BPRS items, CGI total score, and SANS total score. For each of these four responses, we ran the BMDP 5V program (25), a maximum-likelihood, unbalanced repeated measures model ANOVA with unstructured covariance matrices, which is often referred to globally as one of the family of random regression models. Use of BMDP 5V and a regular repeated measures ANOVA program (BMDP 2V) gave us five ANOVAs for assessing the appropriateness and concurrence of results. These analyses were for 1) patients with complete time course data (N=59); 2) patients with all time course data but with last observation carried forward as an approach to missing data (N=81); 3) patients with complete data but for whom we used only their baseline and endpoint values (N=59); 4) patients for whom we used baseline and endpoint data where last observation carried forward determined the endpoint (N=81); and 5) the results of the missing-value random regression runs (BMDP 5V). In all cases, while the numeric answers differed somewhat, the conclusions were not in conflict. Where one analysis found statistical significance, the other four did as well.

RESULTS

One hundred three subjects started the haloperidol phase. They received a mean haloperidol dose of 20 mg/day (SD=10, range 10–40, N=102). Ninety subjects completed the haloperidol trial; nine subjects withdrew consent, two patients were withdrawn for medical reasons, and two were withdrawn for administrative reasons. One patient responded to haloperidol treatment. The haloperidol-treated patients did not show any mean clinical change (mean increase in total BPRS score=1.6%, SD=11.8%; F=0.68, df=1,89, p=0.41). The mean duration of the haloperidol phase was 37 days (SD=13, range=14–64).

Eighty-nine patients began the antipsychotic washout phase of the study. Five patients did not complete the washout; four withdrew consent and one did not qualify because of laboratory abnormalities. Eighty-four patients completed that phase and were randomly assigned to receive either olanzapine or chlorpromazine. Eighty-one patients began active drug treatment (N=42 for olanzapine; N=39 for chlorpromazine); three patients completed the washout and were randomly assigned to a drug but never took the drug because of laboratory and medical abnormalities (all three would have taken chlorpromazine). Thus, 84 patients (42 olanzapine and 42 chlorpromazine) were included in our intent-to-treat analyses.

There were no significant differences between the olanzapine and chlorpromazine groups on any demographic variable (table 1). The characteristics of the patients enrolled at each center are shown in table 2. The two state hospital sites had significantly younger populations than the VA hospital (F=1619.96, df=1,83, p=0.0001). The DSM-III-R diagnoses of the study population were not significantly different by drug group or site.

The daily dose of antipsychotic during the first week of double-blind treatment was 12.5 mg/day of olanzapine or 600 mg/day of chlorpromazine. During the second through eighth weeks of the study, all olanzapine-treated patients received 25 mg/day of the drug. Seven chlorpromazine-treated patients had to have their dosages lowered because of drug intolerance. One of these patients was subsequently dropped from the study for drug intolerance secondary to orthostatic hypotension. All others were ultimately stabilized on the higher dose. The chlorpromazine-treated group received a mean dose of 1173 mg/day (SD=125) in the second through eighth weeks of the study. There was no difference between the groups in the amount or duration of lorazepam use during the study.

There was no significant difference in completion rate for participants receiving either drug: 30 (71%) of the 42 olanzapine patients and 29 (69%) of the 42 chlor~pro~mazine patients completed the study. There were no significant differences in the reasons for dropping out of the study. Of the 25 patients who did not complete the double-blind study, eight (five olanzapine, three chlorpromazine) withdrew consent, seven (five olanzapine, two chlorpromazine) dropped out for lack of efficacy, seven (one olanzapine, six chlorpromazine) experienced an adverse event, and three (two olanzapine, one chlorpromazine) were removed for administrative reasons.

Clinical Efficacy

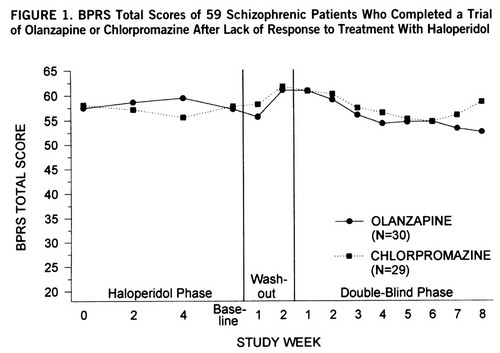

In the 8-week double-blind trial, 7% (N=3) of 42 olanzapine-treated patients, but no chlorpromazine-treated patients, met response criteria during the study (p=0.24, Fisher's exact test). The numbers of subjects who showed a 20%, 30%, or 40% improvement on their total BPRS scores were not different between the drug groups (data not shown). The mean weekly total BPRS scores of the patients who completed the study (N=59) did not differ between the olanzapine group and the chlorpromazine group (F=1.86, df=1,47, p=0.09) (figure 1).

No other primary efficacy measures showed a difference between drug groups (table 3). Olanzapine-treated patients showed a greater therapeutic response on the BPRS anxiety-depression subscale than did chlorpromazine-treated patients (F=5.24, df=1,79, p=0.02) in the last-observation-carried-forward database (N=81) (table 4). How~ever, this effect did not meet the a priori value for significance of 0.01 for a secondary analysis. There were no between-site differences in any of the outcome measures.

Clinical Safety

Adverse reactions (the total number of patients reporting a new or worsened treatment effect at least one time during double-blind treatment) are presented in table 5. The most frequent side effects for the combined study groups were dry mouth, drowsiness/lethargy, and ortho~static changes. Olanzapine was significantly better-tolerated than chlorpromazine. Chlorpromazine caused more dry mouth, orthostatic changes, unsteady gait, and extrapyramidal side effects. Extrapyramidal symptoms decreased in all subjects who completed the study, regardless of drug treatment group (F=16.88, df=1,47, p<0.0001). There was also a decrease in akathisia as indicated by the Barnes Aka~thisia Scale scores (F=6.03, df=1,47, p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study demonstrate no difference in efficacy between olanzapine and chlorpromazine in the treatment of psychotic symptoms in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Overall, neither drug group showed a substantial change in their level of psychosis from their pre~randomization (haloperidol-treated) baseline, and no differences between groups emerged in the analysis of the primary efficacy variables. The dropout rate was low and balanced between drug groups; this allowed not only endpoint and last-observation-carried-forward analyses but also a completers-only ANOVA. Results from these different analytic strategies were similar. The olanzapine group did have a considerably better side effect profile than the chlorpromazine group.

Because there was no clozapine arm in this study, the question of whether this was a “typical” or a “clozapine-sensitive” treatment-resistant group arises. This study had essentially the same entry criteria as the Kane et al. study (9), and our study group was similar in age, racial composition, diagnosis, and duration of hospitalization to the Kane et al. study group. In that group and in other investigators' subsequent work, treatment-resistant groups responded to clozapine (with at least 20% improvement) at rates of 30%–70% (4, 9–12, 26). However, at least 50% of our study group had not responded to an adequate trial of risperidone, which might make this group less comparable to those in prior studies. We have treated 21 patients from our group—all of whom did not respond to olanzapine—with clozapine. To date, 11 patients (52%) have had at least a 20% improvement. Thus, our population does seem to be responsive to clozapine according to this preliminary test.

While no subjects in the present study had previously failed to respond in a trial of clozapine's efficacy, six of 84 patients had previously been treated with clozapine but stopped because of intolerance of side effects. When we dropped these six subjects from the group for an analysis, the outcome remained the same.

The question of whether the olanzapine dosage used in this study was high enough arises because a range of doses was not included. The fixed olanzapine dose was 25 mg/day, a relatively and purposefully high dose compared to the recommended clinical dose range of 5–20 mg/day. This high dose was used in an attempt to answer the challenge that an inadequate dose contributes to a negative result. However, the dose of clozapine required for treatment-resistant schizophrenia is not different from the dose necessary for treating neurolep~tic-intolerant schizophrenia. Therefore, we did not posit the need for a remarkably higher olanzapine dose than the one recommended. It would, nonetheless, be impossible to exclude the possibility of greater efficacy with a higher dose of olanzapine.

The 25-mg/day dose of olanzapine used in this study provided an opportunity to examine olanzapine-induced motor side effects at a relatively high dose. No anticholinergic drugs were used with olanzapine at this dose. No volunteer in the olanzapine group dropped out because of extrapyramidal side effects or suffered even moderate extrapyramidal side effects during the study. The extrapyramidal side effects experienced by both treatment groups in this study were generally mild and transient.

Because clozapine and olan~zapine share many pharmacologic characteristics, differences in clinical efficacy are more surprising than similarities. Olanzapine showed a low motor side effect profile. This profile was similar but not identical to what has already been described with clozapine. Moreover, olanzapine failed to show the spectrum of severe drug side effects typically associated with clozapine; these include agranulocytosis, drooling, seizures, tachycardia, and severe sedation. However, in this subgroup of patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, we also found that olanzapine lacked the unique antipsychotic actions of clozapine. If replicated, these clinical data should prompt the reformulation of pharmacologic theories of dopamine/serotonin balance, D1/D2 dopamine receptor balance, or even A10 selective depolarization blockade as ways of explaining clozapine's unique antipsychotic actions. The higher affinity of olanzapine for monoaminergic receptors in general and its lower affinities for some specific receptors (for example, alpha2, 5-HT7, or nicotinic receptors) remain as candidate explanations for the difference in efficacy between these drugs.

In conclusion, this efficacy study should be repeated with use of a higher dose of olanzapine to rule out the possibility of high-dose response, and this subject group should be further characterized with regard to clozapine response. If additional data are consistent with our present results, then olanzapine will have been shown to lack the special efficacy in nonresponders to neuroleptics that has been demonstrated with clozapine. This result is important in characterizing the degree of clinical similarity between these antipsychotic drugs.

|

|

|

|

|

Received Aug. 19, 1997; revision received Feb. 6, 1998; accepted Feb. 16, 1998. From the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, University of Maryland School of Medicine, and Spring Grove Hospital Center, Baltimore; the Perry Point VA Medical Center, Perryville, Md.; and the Upper Shore Hospital Center, Chestertown, Md. Address reprint requests to Dr. Conley, Maryland Psychiatric Research Center, P.O. Box 21247, Baltimore, MD 21228. Supported in part by NIMH grants MH-47311 and MH-40279. Eli Lilly and Co. provided olanzapine and olanzapine placebo for the study. The authors thank the staff clinicians at Spring Grove Hospital Center, Perry Point VA Medical Center, and Upper Shore Hospital Center and Charles Beasley, M.D., for assistance in this study.

FIGURE 1. BPRS Total Scores of 59 Schizophrenic Patients Who Completed a Trial of Olanzapine or Chlorpromazine After Lack of Response to Treatment With Haloperidol

1 Conley RR, Buchanan RW: Evaluation of treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1997; 23:663–674Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2 Prien RF, Cole JO: High dose chlorpromazine therapy in chronic schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1968; 18:482–495Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3 Davis JM, Casper R: Antipsychotic drugs: clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use. Drugs 1977; 12:260–282Crossref, Google Scholar

4 Essock SM, Hargreaves WA, Dohm FA, Goethe J, Carver L, Hipsh~man L: Clozapine eligibility among state hospital patients. Schizo~phr Bull 1996; 22:15–25Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5 McGlashan TH: A selective review of recent North American long-term followup studies of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1988; 14:515–542Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6 Revicki DA, Luce BR, Weschler JM, Brown RE, Adler MA: Economic grand rounds: cost-effectiveness of clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenic patients. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1990; 41:850–854Abstract, Google Scholar

7 Christison GW, Kirch DG, Wyatt RJ: When symptoms persist: choosing among alternative somatic treatments for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1991; 17:217–245Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8 Barnes TRE, McEvedy CJB: Pharmacological treatment strategies in the non-responsive schizophrenic patient. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1996; 11:67–71Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9 Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H, Clozaril Collaborative Study Group: Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:789–796Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10 Pickar D, Owen RR, Litman RE, Konicki E, Gutierrez R, Rapaport MH: Clinical and biologic response to clozapine in patients with schizophrenia: crossover comparison with fluphenazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992; 49:345–353Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11 Breier A, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Davis OR, Irish D, Summerfelt A, Carpenter WT Jr: Effects of clozapine on positive and negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:20–26Link, Google Scholar

12 Conley RR, Carpenter WT Jr, Tamminga CA: Time to clozapine response in a standardized trial. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:1243–1247Link, Google Scholar

13 Kinon BJ, Kane JM, Johns C, Perovich R, Ismi M, Koreen A, Weiden P: Treatment of neuroleptic-resistant schizophrenia relapse. Psychopharmacol Bull 1993; 29:309–314Medline, Google Scholar

14 Bymaster FP, Hemrick-Luecke SK, Perry KW, Fuller RW: Neurochemical evidence for antagonism by olanzapine of dopamine, serotonin, alpha1-adrenergic and muscarinic receptors in vivo in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996; 124:87–94Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15 Robertson GS, Fibiger HC: Effects of olanzapine on regional Cfos expression in rat forebrain. Neuropsychopharmacology 1996; 14:109–110Crossref, Google Scholar

16 Tollefson GD, Beasley CM Jr, Tran PV, Street JS, Krueger JA, Tamura RN, Graffeo KA, Thieme ME: Olanzapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of schizophrenia and schizoaffective and schizophreniform disorders: results of an international collaborative trial. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:457–465Link, Google Scholar

17 Simpson GM, Varga E: Clozapine: a new and unusual antipsychotic agent. Psychopharmacol Bull 1975; 11:14–15Medline, Google Scholar

18 Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1987Google Scholar

19 Overall JE, Gorham DR: The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10:799–812Crossref, Google Scholar

20 Guy W (ed): ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology: Publication ADM 76-338. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1976, pp 217–222Google Scholar

21 Conley R, Zaremba S, McMullen R, Love R: Evaluating ability to consent in psychotic inpatients (abstract). Schizophr Res 1997; 24:206Crossref, Google Scholar

22 Andreasen NC: Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa, 1983Google Scholar

23 Simpson GM, Angus JWS: A rating scale for extrpyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1970; 212:11–19Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24 Barnes TR: A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry 1989; 154:672–676Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25 Dixon WJ (ed): BMPD Statistical Software Manual, vol 2. Berke~ley, University of California Press, 1992Google Scholar

26 Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Pollack S, Szymanski S, Johns C, Howard A, Kronig M, Bookstein P, Kane JM: Clinical effects of clozapine in chronic schizophrenia: response to treatment and predictors of outcome. Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:1744–1752Link, Google Scholar