Factors Associated With Primary Care Clinicians' Choice of a Watchful Waiting Approach to Managing Depression

Use of watchful waiting, defined as assessment with scheduled follow-up in primary care but no active medication or psychotherapy treatment to manage depression, remains debatable because evidence has provided mixed results. Some research suggests that watchful waiting may be an appropriate management approach for patients who present with less severe depressive disorders for several reasons ( 1 , 2 , 3 ). Many patients with minor depression recover spontaneously within two to four weeks and thus may not need treatment if they do not present with severe symptoms, substantial functional impairment, or long illness duration. Even with specific treatment, these patients may fare no better than they would if they received supportive care or watchful waiting ( 4 ). Additionally, many patients with depressive symptoms related to normal bereavement are good candidates for watchful waiting because symptoms often subside within two months. A watchful waiting approach may also promote patient-centered care by allowing for patient preference when there is no definitive treatment choice.

Other studies and evidence-based guidelines, however, suggest that pharmacotherapy or structured forms of psychotherapy should be used as a first-line treatment for major depressive disorder ( 1 , 5 ). Illuminating the factors associated with primary care clinicians' use of watchful waiting may address gaps in current depression management guidelines and clinician education.

For many primary care patients with depression, their depression goes unrecognized, and even when their depression is recognized, they do not receive evidence-based care ( 6 , 7 ). Among those offered treatment, nonadherence rates are still high: as many as one-third of patients discontinue medications after one month, and nearly half discontinue medications after three months ( 8 ). Thus it is difficult to know whether clinicians choose watchful waiting to benefit the patient or to cope with numerous barriers, including patient reluctance to acknowledge symptoms or initiate and maintain treatment ( 9 ), and practical barriers, such as insufficient insurance coverage and lack of transportation, child care, or flexible work schedules ( 10 ). Barriers may also stem from the primary care clinician's competing demands—that is, addressing patients with multiple medical problems, time constraints, and difficulty coordinating care with mental health specialists ( 11 ). Clinicians may also have limited training, knowledge, and skills for the detection and management of depression ( 12 ). Clinicians may be uncomfortable treating depression or believe that it poses an unmanageable burden to their practice ( 13 ). A consistent deficiency in primary care management of depression is the lack of resources to provide adequate follow-up, monitor symptom progression, and adjust the treatment regimen. These barriers are interlinked with structure and organization of primary care practice ( 14 ), including clinician financial incentives that may drive treatment choice ( 15 ).

On the basis of social psychological theories about decision making—for example, social-cognitive theory ( 16 ), the theory of planned behavior ( 17 , 18 ), and the health belief model ( 19 , 20 )—we hypothesized that clinicians who perceive no barriers to treatment and who have more knowledge and confidence will be more likely to use a watchful waiting approach for treating depression. Our framework incorporates individual clinician and clinician-level patient factors—that is, demographic characteristics and depression severity for each clinician's patients in the study—and system factors—such as organizational integration between primary care and behavioral health services ( 14 ) in influencing clinicians' tendency to use a watchful waiting approach.

In this article, we identify patient, clinician, and system factors that are associated with primary care clinicians' tendency to use a watchful waiting approach; data were from the Partners in Care (PIC) study ( 21 , 22 ). A better understanding of factors associated with a higher tendency for clinicians to use watchful waiting to manage their patients with depression can provide information about clinician values regarding depression care management and can identify and address barriers to optimal depression care in primary care settings.

Methods

Participants

We analyzed data from 167 primary care clinicians (92 percent of 181 clinicians eligible for this study) from 46 practices of seven managed care organizations (MCOs) across the United States who participated in the PIC study and from their 1,187 patients with depression. Within each MCO, we categorized clinical units (or clinics), which could be a single clinic, a cluster of small clinics, or a clinical care team within a large clinic. We then grouped these clinics into blocks of three within each MCO, matching on the primary care clinician's specialty mix; the patient's demographic characteristics, including racial and ethnic characteristics; and level of behavioral health integration. Within each block of matched clinics, we randomly assigned one clinic each to two quality improvement programs (enhanced medication and enhanced psychotherapy) and usual care. Additional information about the study design is available on the PIC Web site (www.rand.org/health/projects/pic).

Measures

Data were collected by sending self-administered mail-back surveys to clinicians (February 1996 through March 1996) and patients (May 1996 through September 1996) before the study interventions were fully under way (June 1996). The surveys consisted of batteries that have been evaluated previously for reliability and validity and batteries developed specifically for this study.

The following scenario was used to depict a patient with symptoms of major depressive disorder presenting for treatment: "A woman in her 30s with prepaid insurance comes into your office today reporting that she has been increasingly depressed over the past two months, with disturbed sleep, decreased appetite, persistent hopelessness, and difficulty with concentration. She is not currently suicidal. She has missed a few days of work due to her depression this month. Her physical examination is normal." We pretested this depression scenario during the development of the PIC instrument. The practicing clinicians in two focus groups of five or six clinicians found it realistic and thought that it contained the core information needed for a decision about depression care management.

In response to the scenario, clinicians rated their proclivity toward different management approaches as the first-line treatment: assess but not treat at this time, personally prescribe medications, personally counsel or provide psychotherapy, refer to mental health specialty, or refer to patient education or self-help program. Each of these five items was scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, very unlikely, to 5, very likely. We operationalized watchful waiting using the first item, assess but not treat at this time. For descriptive analyses, we created a dichotomous measure scored as positive if the clinician reported being likely or very likely to choose a watchful waiting approach and used the 5-point item in multivariate analyses.

Primary care clinician characteristics

Demographic and professional background. Clinician characteristics (from clinician report) included clinician type (internal medicine physician, general or family physician, or nonphysician, for example, physician assistant or nurse practitioner), board certification in their specialty, number of years in professional practice, gender, ethnicity, and the reported percentage of weekly visits with patients who have major depression (as a proxy for amount of experience treating depression).

Knowledge. We included two separate scales to assess clinician knowledge of depression treatment, including a four-item psychotherapy scale and a six-item medication scale (details are available elsewhere) ( 12 , 14 ).

Attitudes and reported practice. Clinicians reported whether they felt a "need to change or improve the way they manage patients with depression"; the item was scored as a binary measure to indicate "definitely" need to improve. We included two items to assess clinicians' perceived skill about diagnosing depression and providing medication for depression. These items were scored from 1 to 4, with a score of 4 meaning "very skilled." We also examined an item that asked clinicians about the percentage of patients (in a typical month) for whom they schedule a follow-up visit without starting treatment among patients they see with moderate to severe depression. Response options ranged from 1 to 5 (none, 25 percent or less, 26 to 50 percent, 51 to 75 percent, and 76 to 100 percent).

System characteristics

We included measures for selected barriers to optimal treatment for depression that have been identified in previous analyses ( 12 , 14 ) to be important predictors of depression-related practices. These barriers were "mental health professionals are not available," "inadequate time to provide follow-up," and "medical problems are more pressing." Clinicians scored their perceptions of these barriers as 1, does not limit; 2, limits somewhat; or 3, limits a great deal. We included an indicator of whether or not the clinician reported using the guidelines of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR, now the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality) ( 23 , 24 ) for the treatment of depression, and we included a binary indicator for clinicians who routinely refer almost all patients with major depression to mental health specialty treatment. We also included a binary indicator of whether or not the clinician worked in a staff- or group-model organization compared with a network or independent practice model ( 14 ).

Patient characteristics

Depression severity. Patient characteristics were assessed with a set of rate measures representing the percentage of study patients with a given criterion for each clinician. We included an indicator of depression severity; the percentage meeting the cutoff point on a revised version ( 25 ) of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) ( 26 ). This revised scale is based on 13 items from the original 20-item CES-D and ten new items that reflect changes made to the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ( DSM-IV ). Possible scores on the scale range from 0 to 69, and the scale is rescaled to range from 0 to 100, first by taking the difference between the raw score and the minimum score in the patient sample and then by dividing through the range of the score among the sample patients.

Chronic medical conditions, gender, and ethnicity. We also included rates of patients reporting two or more chronic medical conditions, rates of patients who were female, and rates of patients who were nonwhite. Because 12 of the 167 clinicians did not have visits with PIC study patients, the sample size was reduced to 155 in the multivariate analyses that included these rates.

Statistical analysis

We evaluated the face validity of the scenario-based clinician measure of watchful waiting by examining its association with clinicians' reports of the extent to which they schedule a follow-up visit without starting treatment for their patients with moderate to severe depression. We used Student's t tests and chi square analyses to examine bivariate relationships between each clinician, patient, and system characteristic and proclivity to choose watchful waiting for depression. Next, we examined the relative effects of the variables in multilevel regression models by entering the variables in sets according to our conceptual model, making sure to retain variables that were significant in bivariate analyses. In final models, we adjusted standard errors using the sandwich estimator (also known as robust variance estimator) ( 27 ) for the nesting of patients within clinic. We imputed missing data elements five times, forming five replicates of complete data. All analyses were conducted five times on each data set, and then results were synthesized by using Rubin's multiple imputation inference procedure ( 28 , 29 , 30 ). We illustrated significant effects by calculating the adjusted means on the basis of parameters of the regression models.

Results

Outcome validation

Our scenario-based outcome measure of proclivity for watchful waiting was significantly correlated with clinicians' reports of the proportion of patients for whom they typically schedule a follow-up visit without starting treatment (r=.31, p<.001). There was also a trend for clinicians with a higher tendency for watchful waiting to have better knowledge about psychotherapy (p=.06), and clinicians with a higher tendency for watchful waiting tended to have more knowledge about the use of guidelines for the treatment of depression, although these findings were not significant. These data provide support that clinicians interpret the scenario's response item "assess but not treat at this time" as a valid treatment option—for example, true watchful waiting that includes follow-up as opposed to failure to identify and treat depression.

Clinician characteristics

As shown in Table 1 , of the 167 clinicians, 35 percent were women and 69 percent were white, 3 percent were black, 17 percent were Hispanic, and 11 percent were Asian. The mean±SD age of the clinicians was 43.4±9.0 years. Thirty-four percent were internal medicine physicians, 52 percent were family or general practice physicians, 14 percent were nonphysicians (for example, nurse practitioners or physician assistants), and 79 percent were board certified in their specialty. As documented by Meredith and colleagues ( 12 ), clinicians in the PIC study had similar characteristics at baseline across intervention condition, although there was a trend for fewer nonphysicians, women, and nonwhite clinicians in the enhanced-medication condition compared with the enhanced-psychotherapy or usual-care conditions. These characteristics were included in all analyses to adjust for preexisting differences.

|

Factors associated with watchful waiting

Overall, 34 clinicians (20 percent) reported that they would be likely or very likely to choose a watchful waiting approach to managing the patient with symptoms of major depressive disorder described in the scenario.

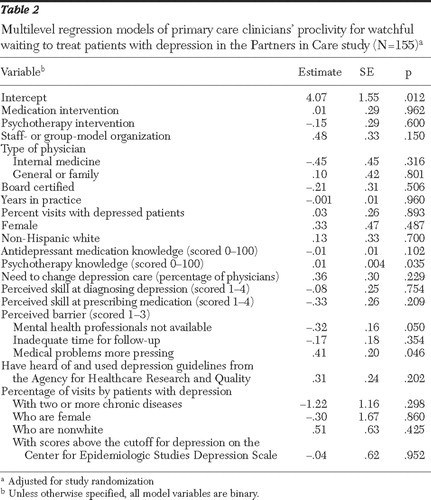

As shown in Table 2 , three factors were significantly associated (p≤.05) with clinicians' proclivity for watchful waiting in managing depression. Figure 1 illustrates the factors that accounted for significant variation in clinicians' tendency to use a watchful waiting approach. Clinicians with more knowledge about psychotherapy treatment for depression were more likely to watch and wait compared with clinicians with less psychotherapy knowledge. Clinicians who perceived no barrier to mental health specialist access were more likely to report watchful waiting compared with clinicians who viewed mental health specialist unavailability as a limiting factor and clinicians who viewed medical problems as competing with ability to provide depression care.

|

Discussion and conclusions

We found that primary care clinicians had an overall low proclivity for using watchful waiting to manage patients described as having symptoms of major depressive disorder (20 percent). This low rate is consistent with the findings of a study that surveyed 1,140 patients and showed that a low percentage of patients (103 patients, or 15 percent of available cases) had a preference for a "wait and see" treatment option (compared with active forms of treatment) ( 31 ). And among the 103 patients in the study who chose watchful waiting, only 15 (15 percent) had clinicians who also reported a stronger tendency for watchful waiting.

The data in our study identified system factors, such as competing demands and inadequate follow-up time, that influenced the likelihood of watchful waiting. Clinicians reported a higher tendency for watchful waiting if they had more knowledge about psychotherapy, perceived no barriers to mental health specialist access, or perceived that the need to treat the patient's medical illness was more important than the need to treat his or her mental illness. Perhaps availability of referrals gives clinicians more comfort to utilize watchful waiting despite lack of support from guidelines, because they can be confident that a mental health specialist will be available should a patient's symptoms worsen. Alternatively, if referral access is limited, clinicians may find the watchful waiting option too risky. Or clinicians may feel the need to attend to medical problems themselves and refer patients who have co-occurring depression to a mental health specialist. Our findings support prior studies and theories suggesting that system factors may influence primary care clinicians' choice of a depression management approach ( 17 , 18 , 32 ). Recognizing and addressing these factors on a system level may help clinicians choose an appropriate approach to depression management.

If clinicians choose watchful waiting paired with follow-up and monitoring, they may be able to determine at a later time that it is appropriate to begin treatment. Thus the "watchful" part of watchful waiting is essential because the decision between watchful waiting and active treatment becomes ineffective without proper follow-up as part of the strategy. However, this raises the question of what constitutes good follow-up care. The American Psychiatric Association recommends once a week for routine cases of major depression ( 33 ), but this may be unrealistic given the burdens of primary care practice. Recent studies show that telephone medication management by nurse practitioners and physician assistants is a potential alternative to in-person contact ( 34 ). Studies have also demonstrated that clinician and system obstacles to depression care can be overcome through collaborative initiatives, which are now becoming more common in primary care practices ( 3 , 35 , 36 , 37 ). Even when optimal models of care are in place, other factors such as patient preferences and stage of readiness to accept a diagnosis and receive treatment continue to make watchful waiting an important clinical option. Other technological approaches, including use of e-mail are fruitful means for follow-up care.

A limitation of this study is the possible ambiguity of using the survey item, "assess but not treat at this time." Although intended to define the scenario-based outcome of watchful waiting, participants may have misconstrued this item as "no treatment at all." However, we found that the percentage of clinicians who chose watchful waiting for the patient in the scenario was similar to the percentage who chose watchful waiting for their actual patients.

The use of a hypothetical patient scenario can limit validity. However, we found that these clinicians' reports were highly consistent with patients' reports about treatment preferences, which gives face validity to the scenario-based measures. We also pretested the vignette to enhance its validity. Additionally, past research suggests that vignettes produce scores that are better than chart abstraction and closer to the gold standard of scores obtained for standardized patients ( 38 , 39 ) when measuring treatment decisions. Thus vignettes are a valid, cost-effective, and comprehensive method for measuring the process of care provided in actual clinical practice.

As noted in previous studies based on data from PIC ( 12 ), this study was based on self-report and thus may be subject to the common threats to reliability and validity relative to direct observation. Additionally, although the sample size of clinicians was modest (155 clinicians who had visits with PIC study patients), this was a relatively large sample of primary care clinicians using mail-back surveys. A related concern for this small data set is the large number of right-hand-side variables (k=21) that were tested in the regression analysis. Although such small samples with a large number of variables risk not identifying true effects, we included only variables that were necessary to account for design effects and those for which we had clear hypotheses or demonstrated bivariate associations. Thus our findings are likely to be on the conservative side.

The age of the data should be noted. Although clinicians' reports from 1996 may not reflect current clinical practice, a recent 2006 study on watchful waiting ( 40 ) suggests that the watchful waiting phenomenon is still relatively understudied with no clear clinical practice guideline of its value in primary care.

Despite these limitations, findings from this work have and will make an impact in the following ways. The data cast the management of depression in new light by elucidating the factors involved in deciding not to provide active treatment. Specifically, we have identified which barriers may influence proclivity to provide care for depression. This information is important because some patients with depression symptoms may not benefit from active treatment. Our findings point to the utility of having watchful waiting in clinicians' armamentarium but emphasize the need to educate clinicians on recommending watchful waiting on the basis of clinical need rather than on the basis of barriers related to patient demographic characteristics or systems.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by grant 048121 to Dr. Meredith from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation under the Depression in Primary Care program. The Partners in Care study was funded by grant HS-08349-02 to Kenneth B. Wells, M.D., from the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. The authors acknowledge the participating managed care organizations and the participating primary care clinicians and patients who gave their time and efforts to the study: Allina Medical Group (Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota), Patuxent Medical Group (Columbia, Maryland), Humana Health Care Plans (San Antonio, Texas), MedPartners (Los Angeles), PacifiCare of Texas (San Antonio), Valley-Wide Health Services (San Luis Valley, Colorado), and GreenSpring Mental Health Services (Columbia, Maryland). The authors also thank Kenneth B. Wells, M.D., M.P.H., the principal investigator of Partners in Care (PIC), and the other co-principal investigators and staff of PIC.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Whooley MA, Simon GE: Managing depression in medical outpatients. New England Journal of Medicine 343:1942-1950, 2000Google Scholar

2. Williams JW Jr, Barrett J, Oxman T, et al: Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care: a randomized controlled trial in older adults. JAMA 284:1519-1526, 2000Google Scholar

3. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: impact on depression in primary care. JAMA 273:1026-1031, 1995Google Scholar

4. Lynch D, Tamburrino M, Nagel R, et al: Telephone-based treatment for family practice patients with mild depression. Psychological Reports 94:785-792, 2004Google Scholar

5. Barrett JE, Williams JW, Oxman TE, et al: Treatment of dysthymia and minor depression in primary care. Journal of Family Practice 50:405-412, 2001Google Scholar

6. Williams JW, Rost K, Dietrich AJ, et al: Primary care physicians' approach to depressive disorders: effects of physician specialty and practice structure. Archives of Family Medicine 8:58-67, 1999Google Scholar

7. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55-61, 2001Google Scholar

8. Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W, et al: The role of the primary care physician in patients' adherence to antidepressant therapy. Medical Care 33:67-74, 1995Google Scholar

9. Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, et al: Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. American Journal of Public Health 89:1328-1333, 1999Google Scholar

10. Miranda J, Munoz R: Intervention for minor depression in primary care patients. Psychosomatic Medicine 56:136-141, 1994Google Scholar

11. Nutting PA, Rost K, Smith J, et al: Competing demands from physical problems: effect on initiating and completing depression care over 6 months. Archives of Family Medicine 9:1059-1064, 2000Google Scholar

12. Meredith LS, Jackson-Triche M, Duan N, et al: Quality improvement for depression enhances long-term treatment knowledge for primary care clinicians. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:868-877, 2000Google Scholar

13. Main DS, Luiz LJ, Barrett JE, et al: The role of primary care clinician attitudes, beliefs, and training in the diagnosis and treatment of depression. Archives of Family Medicine 2:1061-1066, 1993Google Scholar

14. Meredith LS, Rubenstein LV, Rost KM, et al: Treating depression in staff-model vs network-model managed care organizations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 14:39-48, 1999Google Scholar

15. Hillman AL, Pauly MV, Kerstein JJ: How do financial incentives affect physicians' clinical decisions and the financial performance of health maintenance organizations? New England Journal of Medicine 321:86-92, 1989Google Scholar

16. Bandura A: Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall International, 1986Google Scholar

17. Ajzen I, Fishbein M: Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1980Google Scholar

18. Fishbein M, Ajzen I: Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior. Reading, Mass, Addison-Wesley, 1975Google Scholar

19. Maiman LA, Becker MH: The Health Belief Model: origins and correlates in psychological theory. Health Education Monographs 2:336-353, 1974Google Scholar

20. Rosenstock IM: Historical origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Education Monographs 2:328-335, 1974Google Scholar

21. Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Schoenbaum M, et al: Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 283:212-220, 2000Google Scholar

22. Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unützer J, et al: Evidence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Affairs 18(5):89-105, 1999Google Scholar

23. Depression Guideline Panel: Clinical Practice Guideline, Depression in Primary Care: Volume 1: Detection and Diagnosis. AHCPR pub no 93-0550. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

24. Depression Guideline Panel: Clinical Practice Guideline, Depression in Primary Care: Volume 2: Treatment of Major Depression. AHCPR pub no 93-0551. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

25. Orlando M, Sherbourne CD, Thissen D: Summed-score linking using item response theory: application to depression measurement. Psychological Assessment 12:354-359, 2000Google Scholar

26. Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: a self-reported scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385-401, 1977Google Scholar

27. McCaffrey DF, Bell RM: Bias reduction in standard errors for linear regression with multi-stage samples. Survey Methodology 28:169-181, 2000Google Scholar

28. Rubin DB: Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, Wiley, 1987Google Scholar

29. Rubin DB: Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association 91:473-489, 1996Google Scholar

30. Schafer JL: Monographs on Statistics and Applied Probability: Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. London, Chapman and Hall, 1997Google Scholar

31. Dwight-Johnson M, Meredith LS, Hickey SC, et al: Influence of patient preference and primary care clinician proclivity for watchful waiting on receipt of depression treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

32. Jaen CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA: Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. Journal of Family Practice 38:166-171, 1994Google Scholar

33. American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 157(suppl 4):1-45, 2000Google Scholar

34. Symons L, Tylee A, Mann A, et al: Improving access to depression care: descriptive report of a multidisciplinary primary care pilot service. British Journal of General Practice 54:679-683, 2004Google Scholar

35. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al: Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:2836-2845, 2002Google Scholar

36. Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE, Williams JW Jr, et al: Re-engineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care: cluster randomized controlled trial. British Medical Journal 329:epub, 2004. Available at bmj.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/full/329/7466/602Google Scholar

37. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF III, et al: Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 291:1081-1091, 2004Google Scholar

38. Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, et al: Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality [comments]. JAMA 283:1715-1722, 2000Google Scholar

39. Veloski J, Tai S, Evans AS, et al: Clinical vignette-based surveys: a tool for assessing physician practice variation. American Journal of Medical Quality 20:151-157, 2000Google Scholar

40. Hegel MT, Oxman TE, Hull JG, et al: Watchful waiting for minor depression in primary care: remission rates and predictors of improvement. General Hospital Psychiatry 28:205-212, 2006Google Scholar